Venice Biennale: Anxious voids in Ignasi Aballí's Spanish Pavilion

recessed.space went to the vernissage week of the 59th Venice Biennale of Art to find the best pavilions, artists, and ideas which intersect with architecture & place. First up is an interview with Spanish artist Ignasi Aballí & an exploration of his uncanny & anxious architecture full of possibilities, created with a simple shift of the plan.

It is a simple idea, but one full of complications and

possibilities. To rebuild a building inside the current one - a 1:1 version

contained within the original, but with a 10 degree rotation. When artist Ignasi

Aballí noticed that the footprint of the Spanish Pavilion was sitting at a

slightly shifted angle to its neighbouring Belgian and Dutch pavilions, he set

out correct it and align its internal spaces to those next door. There

is no other work to see than the space itself.

![]()

The work, however, is less simple. To physically construct a simulacrum within the original is no mean feat, and required intense architectural intervention, a build which belies the way in which it is apparently lightly dropped into its host space. The original and 10° shifted forms are then smoothly combined, as if a glitch in a computer render, creating a new conjoined architecture full of narrowing angles, confused passageways, diverging and converging walls, and unexpected connections.

Titled Corrección, Aballí considers this a microcosm of the wider urban fabric of the city: “Some areas are visible but not accessible - you can see inside but you can not be inside. This is very special, and I think it's very close to the architecture in Venice, the city is full of these dark and hidden places, dead ends.”

![]()

![]()

figs.ii,iii

With no other artistic objects, paintings, or sculptures in the space, the white walls are all there is for visitors to see. In such a white space, the light conditions take centre stage, and having opened up the original building’s rooflights—usually blocked up in order control the space for artistic intervention and projection—the passing sun causes the new conjoined architectures to create a symphony of shade.

![]()

![]()

It is also a political act. What does it mean to be a geographic neighbour of another state, or another person, idea, or system? The artist, based in Barcelona at a time of rising calls for Catalan independence, suggests the work also conjures “a disjointed idea of Spain”.

If externally we (either personally, institutionally, politically, or nationally) remain independent and different to others—just as the external form and façades of the Spanish pavilion remain different in form and angle to the Dutch and Belgian buildings—how do we realign ourselves internally to conform or silently relate to extraneous forces? There are spaces within the new plan which are completely enclosed, not accessible to light or person. There is, perhaps, an anxiety in such spaces of darkness and inaccessibility, what can grow or emerge in such recesses we cannot see?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The intervention was a collaboration with Barcelona architecture firm MAIO, and while appearing as a solid and seamlessly connected sculptural form, the white walls were already losing their immaculate white finish even in week one of Biennale. Pointing at a scuff mark on the wall about a metre from the ground where an opening is cut narrow by the intervention and visitors have rubbed bags against the white walls, Aballí says: “There are many, many things I have worked with before—light, time, traces. Now with people passing, leaving these lines, i too will leave them. I will look at the patterns and dirt exactly like a trace, the memory experience of being here, so we won’t repaint.”

![]()

![]()

figs.xi-xiii

The idea of creating a new plan of a known place is not just within the Spanish Pavilion, but also deeper into the city of Venice. Alongside the architectural intervention, Aballí also created a series of small free artist books which he has distributed around the city, locatable by an abstract map available from the pavilion, touching on themes including landscape, horizons, stories, and inventory.

“I didn't know these places before because they are not the main tourist Venice. The idea is to propose an alternative visit to the city and to discover these everyday places like a drugstore, a kiosk, or a small bookshop focusing on Venice books. [This will] help people visit another Venice which is not like the official one everybody knows, the iconic the image of the city, but to take the people to another parallel city.”

![]()

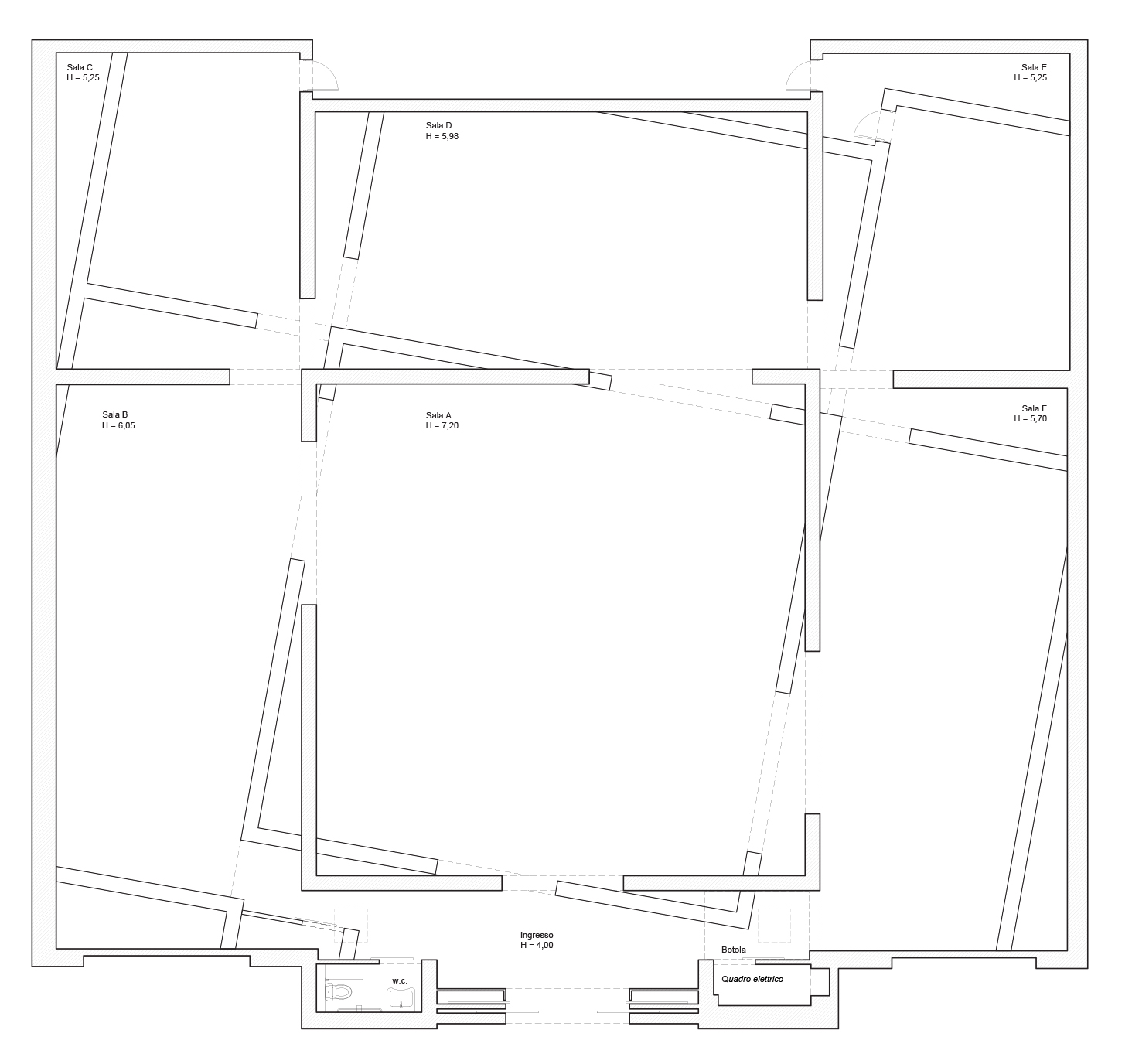

fig.i

The work, however, is less simple. To physically construct a simulacrum within the original is no mean feat, and required intense architectural intervention, a build which belies the way in which it is apparently lightly dropped into its host space. The original and 10° shifted forms are then smoothly combined, as if a glitch in a computer render, creating a new conjoined architecture full of narrowing angles, confused passageways, diverging and converging walls, and unexpected connections.

Titled Corrección, Aballí considers this a microcosm of the wider urban fabric of the city: “Some areas are visible but not accessible - you can see inside but you can not be inside. This is very special, and I think it's very close to the architecture in Venice, the city is full of these dark and hidden places, dead ends.”

figs.ii,iii

With no other artistic objects, paintings, or sculptures in the space, the white walls are all there is for visitors to see. In such a white space, the light conditions take centre stage, and having opened up the original building’s rooflights—usually blocked up in order control the space for artistic intervention and projection—the passing sun causes the new conjoined architectures to create a symphony of shade.

figs.iv-vi

It is also a political act. What does it mean to be a geographic neighbour of another state, or another person, idea, or system? The artist, based in Barcelona at a time of rising calls for Catalan independence, suggests the work also conjures “a disjointed idea of Spain”.

If externally we (either personally, institutionally, politically, or nationally) remain independent and different to others—just as the external form and façades of the Spanish pavilion remain different in form and angle to the Dutch and Belgian buildings—how do we realign ourselves internally to conform or silently relate to extraneous forces? There are spaces within the new plan which are completely enclosed, not accessible to light or person. There is, perhaps, an anxiety in such spaces of darkness and inaccessibility, what can grow or emerge in such recesses we cannot see?

figs.vii-x

The intervention was a collaboration with Barcelona architecture firm MAIO, and while appearing as a solid and seamlessly connected sculptural form, the white walls were already losing their immaculate white finish even in week one of Biennale. Pointing at a scuff mark on the wall about a metre from the ground where an opening is cut narrow by the intervention and visitors have rubbed bags against the white walls, Aballí says: “There are many, many things I have worked with before—light, time, traces. Now with people passing, leaving these lines, i too will leave them. I will look at the patterns and dirt exactly like a trace, the memory experience of being here, so we won’t repaint.”

figs.xi-xiii

The idea of creating a new plan of a known place is not just within the Spanish Pavilion, but also deeper into the city of Venice. Alongside the architectural intervention, Aballí also created a series of small free artist books which he has distributed around the city, locatable by an abstract map available from the pavilion, touching on themes including landscape, horizons, stories, and inventory.

“I didn't know these places before because they are not the main tourist Venice. The idea is to propose an alternative visit to the city and to discover these everyday places like a drugstore, a kiosk, or a small bookshop focusing on Venice books. [This will] help people visit another Venice which is not like the official one everybody knows, the iconic the image of the city, but to take the people to another parallel city.”

fig.xiv

Ignasi Aballí was born in Barcelona, 1958, the city he still lives & works in. Graduating with a BA in Fine Art from the University of

Barcelona, he has had several solo exhibitions including at MACBA in Barcelona (2005), Fundação de Serralves in Porto (2006), IKON Gallery in Birmingham

(2006), ZKM in Karlsruhe (2006), Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil

(2010), Museo Artium in Vitoria, Spain (2012), Museo Nacional Centro de Arte

Reina Sofía, Madrid (2015), Fundación Joan Miró, Barcelona (2016), Museo de

Arte de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá (2017), Galeria Kula

(Split), and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, Croatia (2018).

He has taken part in the 52nd Venice Biennale (2007), the

8th Sharjah Biennial (United Arab Emirates, 2007), the 11th Sidney Biennial

(1998), the 4th Guangzhou Triennial (2012), and the 13th Cuenca Bienal

(Ecuador, 2016). He was awarded the Joan Miró Prize in 2015.

www.ignasiaballi.net

MAIO is an architectural office based in Barcelona & New York that works on spatial systems which allow variation and change through time. MAIO’s projects embrace the ever-changing complexity of everyday-life while providing a resilient, compromised & clear architectural response.

www.maio-architects.com

www.maio-architects.com

visit

Corrección, by Ignasi Aballí can be visited at the Spanish

Pavilion in the Giardini for the 59th International Art Exhibition La Biennale di

Venezia until 27 November, 2022.

www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022

images

fig.i

Corrección, Ignasi Aballí, 2022.

Site plan showing the Spanish Pavilion with new internal plan, alongside the Belgian Pavilion, courtesy of

Ignasi Aballí & MAIO architects.

fig.ii

Corrección, Ignasi Aballí, 2022.

Scaled floor plan of Spanish Pavilion,

courtesy of

Ignasi Aballí & MAIO architects.

figs.iii-xiv Corrección, Ignasi Aballí, 2022. Photo Claudio Franzini. Courtesy of AECID. ©Claudio Franzini

publication date

30 May 2022

tags

Architecture, Ignasi Aballí, Installation, Intervention, Institutional critique, Light, MAIO, Mapping, Sculpture, Site specific, Space, Spatial, Spain, Spanish Pavilion, Venice, Venice Biennale, Walls

www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022