Being & looking in landscape: Ingrid Pollard’s archaeology

Survey show Ingrid Pollard: Carbon Slowly Turning, at Turner Contemporary in Margate, features a wide selection of the Turner Prize shortlisted artist’s work. Will Jennings extracts elements which focus in on being and looking in landscape.

The final

room of this survey exhibition devoted to the work of Ingrid Pollard is devoted

to landscape. It is dominated by four large synthetic canvases Landscape

Trauma (2001), focusing concentration upon the surface of Farne Island stones,

though they oscillate between macro and micro and could easily be read as aerial

images of nondescript wastelands a la Edward Burtynsky. The eye has to work to

understand what it is looking at.

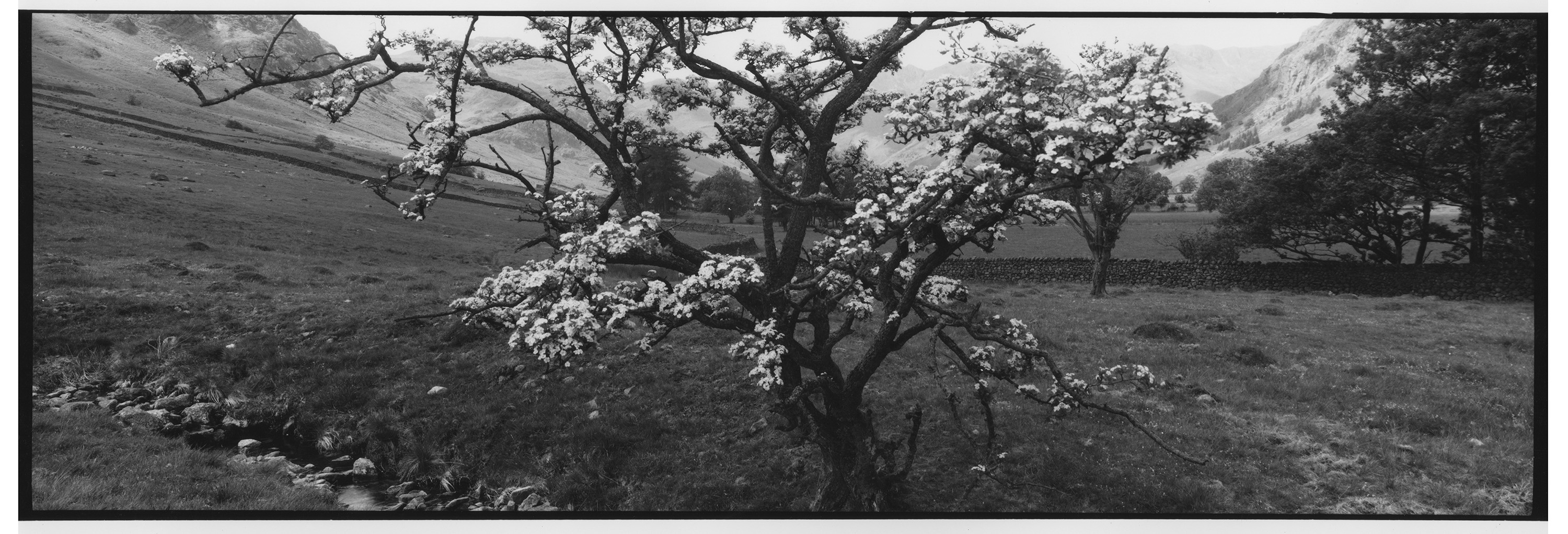

Looking is central to Pollard’s work. In the same room is Bursting Stone (1997), eight black and white gelatin silver prints documenting spaces at the fringe of the Cumbrian National Park, deliberately rejecting the picturesque or iconic in favour of sideways glances and pointing the camera where it shouldn’t be – the pastoral scene of a view across the valley is packed with suburban cul de sacs and a 20th century, another captures a town at night with glaring streetlights breaking the pitch blackness with sinisterness. Who is looking, what are we looking at, are either allowed to?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The work is not just about looking at place, but being in place, and how that place may change when the looking or being is counter to the expected or inbuilt. This is central within one of Pollard’s more well-known pieces, The Cost of the English Landscape (1989), loaned to Turner Contemporary from Tate’s collection. Its arrangement of frames comprising photographs, writing, mappings, and ephemera all speak to the legibility, and cliché, of English landscape – specifically the Lake District.

Images of Pollard and her friends on a hike, black bodies populating the terrain of Beatrix Potter and William Wordsworth, question those clichés and presumptions. Sellafield and industrialisation are as central as romance and the sublime, but it’s about how such places are embodied, specifically by people usually not included in such romantic and nostalgic narratives and representations. Race and class, and through them Englishness and ownership, are pulled into focus with the words “KEEP OUT”, “PRIVATE PROPERTY”, and “NO TRESPASS”.

![]()

![]()

The picturesque is a deliberately beautiful, and beautifying, control of the frame – whether that frame is one of canvas, camera, or the built landscape itself. It’s also a tool of control, to either directly manipulate place as in the work of Capability Brown – who violently reformed the land to suit his version of sublime perfection – or by manipulating the representation and understanding of place, predominantly through art.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.vii-x

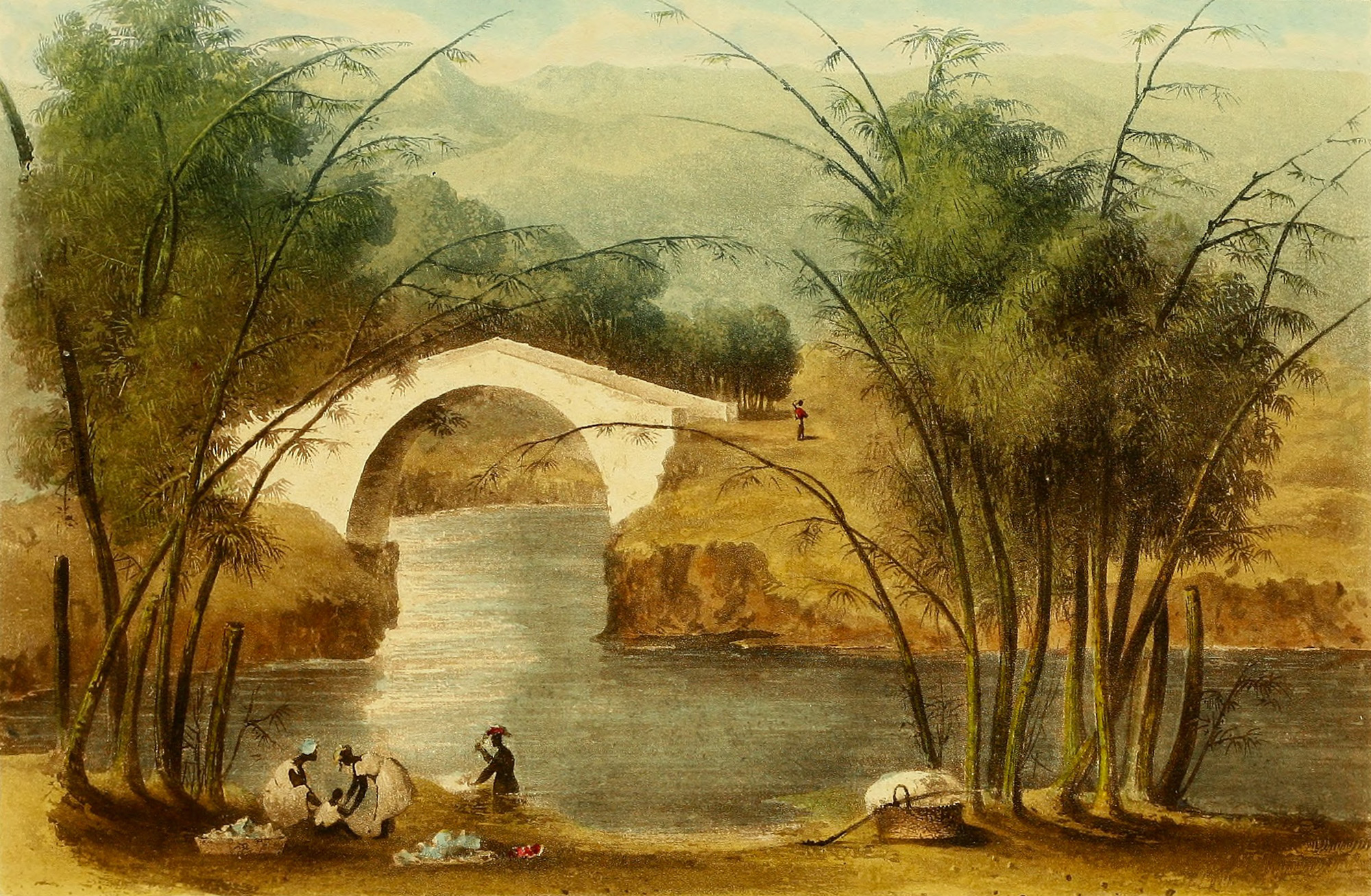

Visual representation can also be used in violent ways. In 1825 James Hakewell published A picturesque tour of the island of Jamaia,[1] in which he naively drew scenes from the island to manifest both its physical beauty and manmade improvements to a readership back in London, at the same time that William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and others had formed the Anti-Slavery Society to argue for the abolition act, which finally arrived in 1833.

Hakewell’s publication, and his deployment of the familiar beautifying language of picturesque composition, was a deliberate act of softening the violence of the ongoing enslaved labour force, presenting a bountiful landscape of relaxed work and human invention which only makes life easier, presenting the architectural and political landscape as apolitical and an empire-improved place.

![]()

![]()

figs.xi,xii

They came to mind when looking at a series of works by Pollard looking at the same island, just sixty years later. The Valentine Days series of hand-tinted digital prints (2017) present photographs originally taken in 1891 by Valentine & Sons, two Dundee brothers who travelled the world creating picture postcards of remote and exotic places. Their images were also not inert or apolitical, serving to represent a constructed version of the island, showing it positively to potential property and business investors. Pollard spent hours hand-tinting the images, returning to them a life and colour missing within their function as marketing and place-branding.

This extends to the people and details within the frames. Pollard looked for rendered individuals who were evidently not placed there by the Valentine brothers, who were not simply props in the work of the photograph, but dwelling within their landscape, and looking back at us. She calls them escapees:

“the mysterious faces looking out of a window, those positioned just on the edge of the frame slightly out of focus, the tiny figures in the distance looking back at the photographer…”

![]()

![]()

A vitrine displays Pollard’s sketches and experiments as she seeks to identify and extract these individuals, eyes look out from a window of a cottage straight into the Valentines’ lens, what we are thinking we will never know but she is looking at us in 2022 as much as anyone looking in 1891. It is not just those who are present picked out in these small images, two images show the gateway to Mount Plenty Great House, formerly owned by John Hiatt, owner of 31 slaves.[2] The dry stone wall, shown in photographs set within a picturesque frame with cart track winding through, and then closer to be able to see the detail of the construction work, would have been built by that enslaved labour. Pollard says “I can hear the carriage going along to the house” when she looks at this photograph, the wall constructed by enslaved people being in their place, and the Valentines photograph of it created to sell the place through looking.

![]()

![]()

figs.xv,xvi

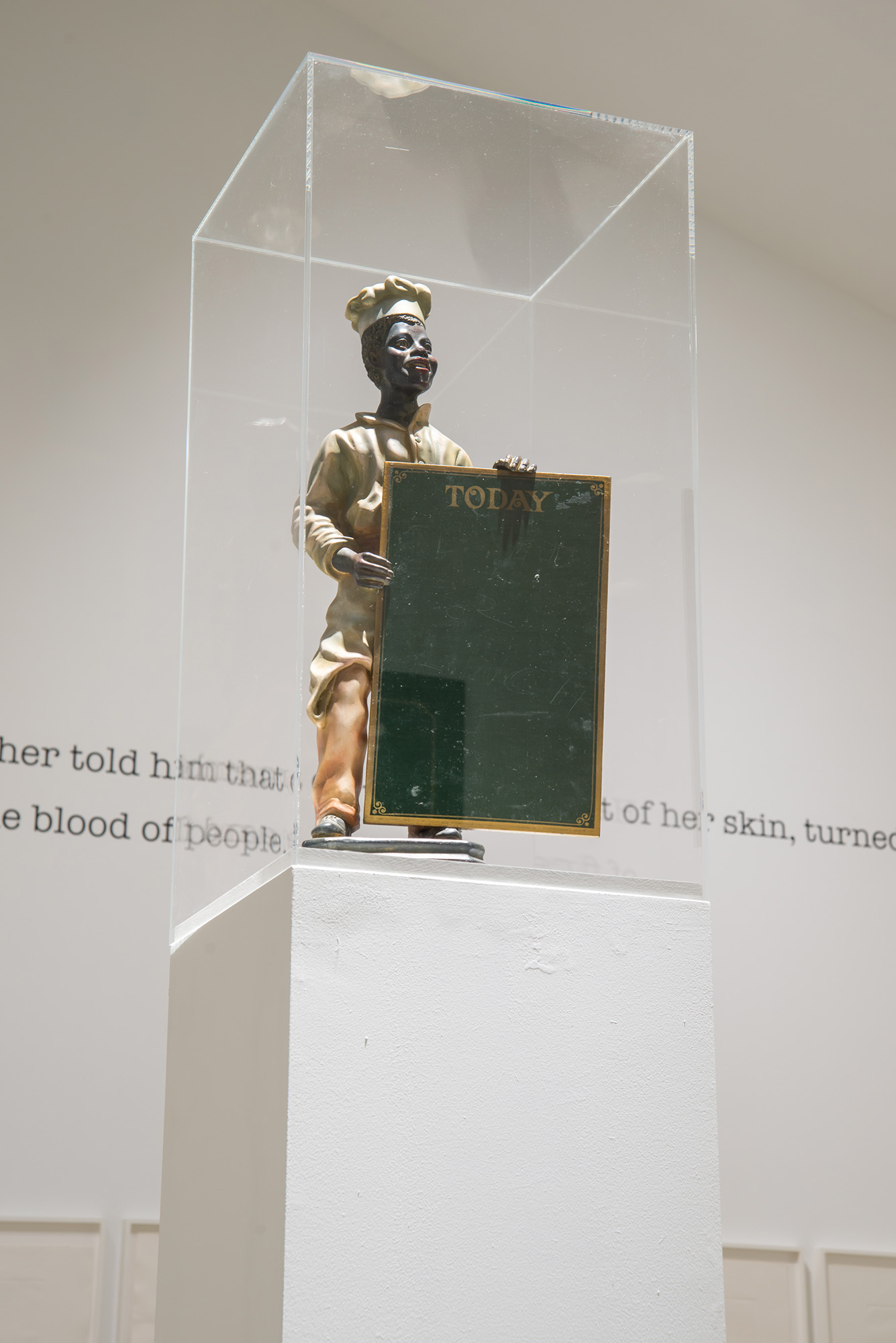

How race and identity are compounded into place is also a live issue, not solely an act of aesthetic archaeology to reconsider previous imagery and representations. A whole room of the Turner Contemporary exhibition is dedicated to elements of Pollard’s changeable work Seventeen of Sixty Eight (2018). It is a carefully curated arrangement of objects, images, and text relating to the African body as represented in British architecture and place.

It is, Pollard says, an act of “exploring hidden heritage within the landscape”, and encapsulates various observations of and literal extractions from architecture, landscape, heritage, and commerce. A photograph of a 1980s suburban terrace, the roadsign reading “BLACKBOY WOOD”. Another photograph of a concealed sign for THE BLACK BOY pub, overgrown by ivy with a secondary sign “LEIGH ARMS” hanging beneath, a gesture of changing times but not one which required the original name to be demounted.

An actual large pub sign, also for “THE BLACK BOY”, hangs up high, and a maquette of a black chef holding a chalkboard is on a tall plinth, reminding us that not all racialised ephemera is from a distant past. A photographic diptych shows a scenic – perhaps picturesque – landscape of a windswept tree under Constable-esque clouds, next to it and located in the same romantic landscape is an agricultural building with an entrance sign, “Blackboys in the Barn”. Pollard says it tells of two readings of the same landscape, adding that the fact it’s never explained why the “Blackboys” are in the barn, or what is happening in there, adds a level of sinisterism.

![]()

![]()

![]()

This collection of haunting and important observations of British places, and how politics, culture, and race are impacted within them, is powerful. Pollard visits all these places herself, sometimes popping into pubs called The Black Boy or similar, striking up innocent conversation with locals. “They always say it’s not about race,” she says, with historical readings of the name rooted in commerce or coal, and she conducts such conversations and observations not with an accusatory tone, but more one of an archaeologist, deeply concerned with looking and reconnecting fragments which would otherwise be lost under the compression of time.

![]()

fig.xx

[1] You can read and see all of this book here:

archive.org/details/picturesquetouro00hake

Looking is central to Pollard’s work. In the same room is Bursting Stone (1997), eight black and white gelatin silver prints documenting spaces at the fringe of the Cumbrian National Park, deliberately rejecting the picturesque or iconic in favour of sideways glances and pointing the camera where it shouldn’t be – the pastoral scene of a view across the valley is packed with suburban cul de sacs and a 20th century, another captures a town at night with glaring streetlights breaking the pitch blackness with sinisterness. Who is looking, what are we looking at, are either allowed to?

figs.i-iv

The work is not just about looking at place, but being in place, and how that place may change when the looking or being is counter to the expected or inbuilt. This is central within one of Pollard’s more well-known pieces, The Cost of the English Landscape (1989), loaned to Turner Contemporary from Tate’s collection. Its arrangement of frames comprising photographs, writing, mappings, and ephemera all speak to the legibility, and cliché, of English landscape – specifically the Lake District.

Images of Pollard and her friends on a hike, black bodies populating the terrain of Beatrix Potter and William Wordsworth, question those clichés and presumptions. Sellafield and industrialisation are as central as romance and the sublime, but it’s about how such places are embodied, specifically by people usually not included in such romantic and nostalgic narratives and representations. Race and class, and through them Englishness and ownership, are pulled into focus with the words “KEEP OUT”, “PRIVATE PROPERTY”, and “NO TRESPASS”.

figs.v,vi

The picturesque is a deliberately beautiful, and beautifying, control of the frame – whether that frame is one of canvas, camera, or the built landscape itself. It’s also a tool of control, to either directly manipulate place as in the work of Capability Brown – who violently reformed the land to suit his version of sublime perfection – or by manipulating the representation and understanding of place, predominantly through art.

figs.vii-x

Visual representation can also be used in violent ways. In 1825 James Hakewell published A picturesque tour of the island of Jamaia,[1] in which he naively drew scenes from the island to manifest both its physical beauty and manmade improvements to a readership back in London, at the same time that William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and others had formed the Anti-Slavery Society to argue for the abolition act, which finally arrived in 1833.

Hakewell’s publication, and his deployment of the familiar beautifying language of picturesque composition, was a deliberate act of softening the violence of the ongoing enslaved labour force, presenting a bountiful landscape of relaxed work and human invention which only makes life easier, presenting the architectural and political landscape as apolitical and an empire-improved place.

figs.xi,xii

They came to mind when looking at a series of works by Pollard looking at the same island, just sixty years later. The Valentine Days series of hand-tinted digital prints (2017) present photographs originally taken in 1891 by Valentine & Sons, two Dundee brothers who travelled the world creating picture postcards of remote and exotic places. Their images were also not inert or apolitical, serving to represent a constructed version of the island, showing it positively to potential property and business investors. Pollard spent hours hand-tinting the images, returning to them a life and colour missing within their function as marketing and place-branding.

This extends to the people and details within the frames. Pollard looked for rendered individuals who were evidently not placed there by the Valentine brothers, who were not simply props in the work of the photograph, but dwelling within their landscape, and looking back at us. She calls them escapees:

“the mysterious faces looking out of a window, those positioned just on the edge of the frame slightly out of focus, the tiny figures in the distance looking back at the photographer…”

figs.xiii,xiv

A vitrine displays Pollard’s sketches and experiments as she seeks to identify and extract these individuals, eyes look out from a window of a cottage straight into the Valentines’ lens, what we are thinking we will never know but she is looking at us in 2022 as much as anyone looking in 1891. It is not just those who are present picked out in these small images, two images show the gateway to Mount Plenty Great House, formerly owned by John Hiatt, owner of 31 slaves.[2] The dry stone wall, shown in photographs set within a picturesque frame with cart track winding through, and then closer to be able to see the detail of the construction work, would have been built by that enslaved labour. Pollard says “I can hear the carriage going along to the house” when she looks at this photograph, the wall constructed by enslaved people being in their place, and the Valentines photograph of it created to sell the place through looking.

figs.xv,xvi

How race and identity are compounded into place is also a live issue, not solely an act of aesthetic archaeology to reconsider previous imagery and representations. A whole room of the Turner Contemporary exhibition is dedicated to elements of Pollard’s changeable work Seventeen of Sixty Eight (2018). It is a carefully curated arrangement of objects, images, and text relating to the African body as represented in British architecture and place.

It is, Pollard says, an act of “exploring hidden heritage within the landscape”, and encapsulates various observations of and literal extractions from architecture, landscape, heritage, and commerce. A photograph of a 1980s suburban terrace, the roadsign reading “BLACKBOY WOOD”. Another photograph of a concealed sign for THE BLACK BOY pub, overgrown by ivy with a secondary sign “LEIGH ARMS” hanging beneath, a gesture of changing times but not one which required the original name to be demounted.

An actual large pub sign, also for “THE BLACK BOY”, hangs up high, and a maquette of a black chef holding a chalkboard is on a tall plinth, reminding us that not all racialised ephemera is from a distant past. A photographic diptych shows a scenic – perhaps picturesque – landscape of a windswept tree under Constable-esque clouds, next to it and located in the same romantic landscape is an agricultural building with an entrance sign, “Blackboys in the Barn”. Pollard says it tells of two readings of the same landscape, adding that the fact it’s never explained why the “Blackboys” are in the barn, or what is happening in there, adds a level of sinisterism.

figs.xvii-xix

This collection of haunting and important observations of British places, and how politics, culture, and race are impacted within them, is powerful. Pollard visits all these places herself, sometimes popping into pubs called The Black Boy or similar, striking up innocent conversation with locals. “They always say it’s not about race,” she says, with historical readings of the name rooted in commerce or coal, and she conducts such conversations and observations not with an accusatory tone, but more one of an archaeologist, deeply concerned with looking and reconnecting fragments which would otherwise be lost under the compression of time.

fig.xx

[1] You can read and see all of this book here:

archive.org/details/picturesquetouro00hake

[2] The Centre for the Study of Legacies of British Slavery at University College London document John Hiatt’s profile, alongside many others, here: www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146641647

Ingrid Pollard (born Georgetown, Guyana) is a photographer, media artist and researcher and one of the leading figures in contemporary British art. Pollard is a graduate of the London College of Printing and Derby University. She has developed a social practice concerned with representation, history and landscape with reference to race, difference and the materiality of lens-based media. Her work is included in numerous collections including the UK Arts Council Collection, Tate and the Victoria & Albert Museum. Pollard is one of four artists nominated for Turner Prize 2022.

www.ingridpollard.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

visit

Ingrid Pollard: Carbon Slowly Turning is exhibited at Turner Contemporary, Margate, until 25 September 2022.

www.turnercontemporary.org

images

fig.i Ingrid Pollard: Carbon Slowly Turning, installation photograph at Turner Contemporary,

© Turner Contemporary

fig.ii-iii Bursting Stone, 1997, 8 digital prints on canvas. Courtesy of the artist. © Ingrid Pollard

fig.iv-vi Ingrid Pollard: Carbon Slowly Turning, installation photograph at Turner Contemporary, © Turner Contemporary

fig.iv Bursting Stone, 1997, 8 digital prints on canvas. Courtesy of the artist. ©

Ingrid Pollard

fig.vii-x Illustrations from A picturesque tour of the island of Jamaica, 1825, by James Hakewill.

fig.xi

Ingrid Pollard: Carbon Slowly Turning, installation photograph at Turner Contemporary, © Turner Contemporary

fig.xii The Valentine Days #5. Crossing A River, J.V. 13950, 2017. Digital prints. Commissioned by Autograph, London & courtesy of Ingrid Pollard, The Caribbean Photo Archive,

© Ingrid Pollard

fig.xiii,xiv Photographs of works from The Valentine Days I & II, as represented in

Ingrid Pollard: Carbon Slowly Turning, a book published to coincide with the exhibition. Published by Philip Wilson Publishers, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2022

fig.xvii-xx

Ingrid Pollard: Carbon Slowly Turning, installation photograph at Turner Contemporary, © Turner Contemporary

publication date

15 July 2022

tags

Being, Capability Brown, Turner Contemporary, Cumbrian National Park, Farne Islands, James Hakewell, Jamaica, Lake District, Landscape, Looking, Picturesque, Photography, Ingrid Pollard, Race, Slavery,

Turner Contemporary, Valentine and Sons

www.turnercontemporary.org