Venice Biennale: Creative games with Francis Alÿs

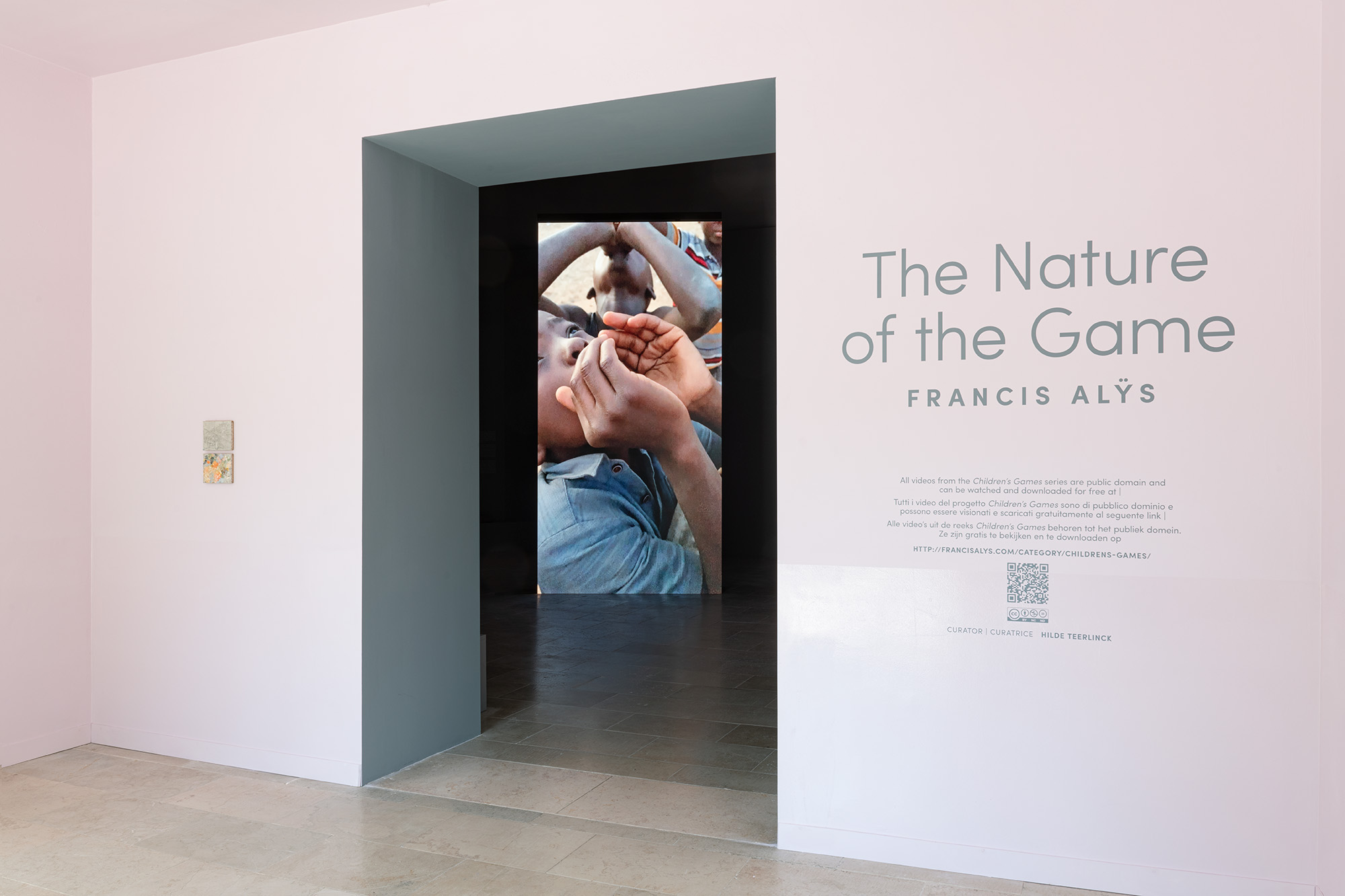

In the next report from recessed.space’s exploration of all things architectural at the Venice Art Biennale, we visit the Belgian Pavilion to find a room packed with playfulness. Francis Alÿs’ simple videos observe children creatively engaging with each other & their landscapes as rituals & experiments of place, seeing joy in all situations & circumstances.

The central chamber of Belgium’s Pavilion at La Biennale is a loud place. Visually, it is packed with large HD monitors displaying looping videos of children playing games all over the world. Sonically, it’s chaotic, the screaming, shouting and sheer joy of the playful kids – each video’s sounds overlapping with the others to create a school-playground soundscape – is such that the noise leaks outside of the main entrance and into the polite and mannered Giardini gardens.

![]()

![]()

Each video is by Francis Alÿs, the Mexican based Belgian artist with a deep interest in geographic and constructed landscapes, using a range of media to test how geopolitics and social relationships are enacted in place. He frequently uses performance and situated video to explore the human and how it comes up against man-made rules, boundaries, or systems. Here, however, he stays resolutely behind the camera’s lens and simply records and relays the simple act of play.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Within the films, simple and short as they are, there is real human emotion. If play is simply exploratory processes not only of human development, but also learning the rules of societal and spatial engagement, then through these short studies one can see how different cultures or people learn and explore their personal situations, landscapes, and cultures.

A boy struggles with a tyre. Nearly as large as himself, he is pushing it up a hill in a near-Sisyphean task, the ground slag of the Étoile du Congo cobalt mine giving way under his feet as he pushes. The same slag is daily sifted by impromptu and unregulated lithium hunters who search through the poisonous dirt to find a material from which our modern, digitised age relies upon. The boy is rooted in this place, its dust, its new topography, and yet from it find naïve escape – once he gets to the top he squeezes his frame into the tyre and rolls himself down the way he came, eventually collapsing on a side, before starting the process over.

fig.vii

In an entirely different landscape, a girl traverses Hong Kong without stepping on the cracks or joints in the pavement. Her movement across the city turns into a dance, engaging with the landscape in ways seemingly remote and forgotten by the countless adults who look upon her from storefronts, vehicles, and the city beyond her imagination. She chants as she weaves the urban fabric, words from behind her covid mask which help ward off the devil who will commit a crime every time a crack is accidentally stood on. For a while, the city is a place of witchcraft and rhythmic magic, and not of capitalism and grind.

“Step on a line, break the devil’s spine,

Step on a crack, break the devil’s back,

Step in a ditch, your mother’s nose will itch,

But if you step in between, everything will be keen!”

fig.viii

In Mexico, empty and unused homes, perhaps abandoned before construction finished, become a military landscape. Instead of bullets, sharp rays of light shoot across the place, each child holding a fragment of broken mirror and using it as a weapon in a wargame to refract the sun towards the enemy.

The unfinished architecture find a new function, light bullets flashing across façades, the empty rooms offering hiding places and strategic spaces of observation as each side strategically illuminates the other. The architectural ruins here losing their connection to a failed capitalist enterprise, taking on a new meaning projected from childish imagination as the sun is projected across them.

fig.ix

These are landscapes of imagination as much as the physical, illustrated no more than in footage of football in Mosul, Iraq. The two teams do not have a football, and instead perform a consensually imagined match in which an invisible football is passed around, flicked on, tackled for, and saved. A boy flies down the wing, kicking up dust from the gravel road in the shadow of buildings destroyed by war, and he crosses the imaginary ball in hoping for a headed goal. Throughout, there only ever seems to be one ball, the deep concentration into the situation focuses everybody towards a single imagined ball, and through that it becomes real.

The film is interrupted to say that in 2015 the Islamic State publicly executed 13 teenagers for watching football on TV. We return to footage of the game, dusk now setting, and suddenly the play is more serious, the invisibility explained. As the film loops, and the surreal football match is returned to, the humour is less funny, the situation more real.

fig.x

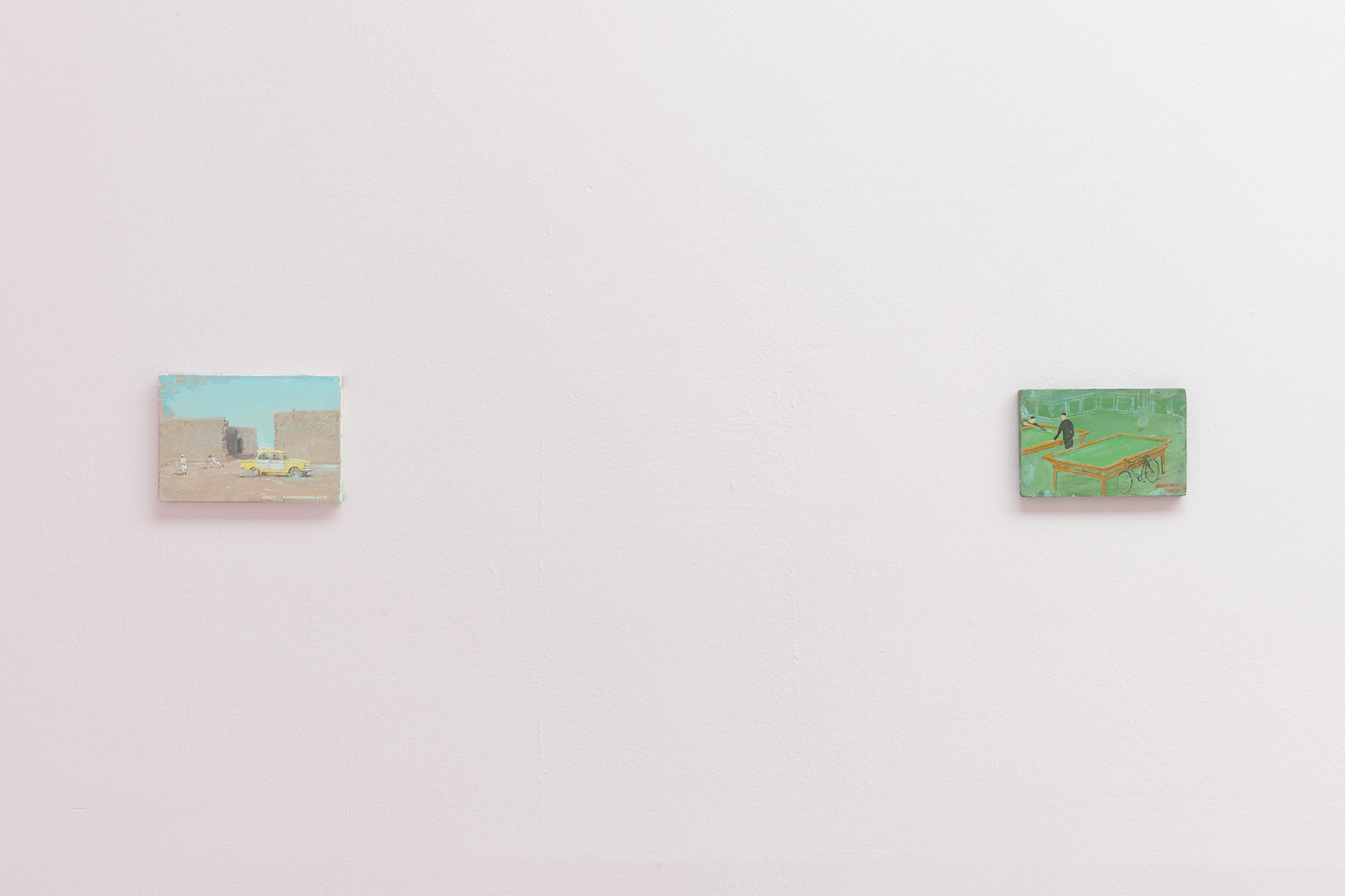

To the side of the central cacophonous space of shouting, screaming, and playful children were two anterooms with small paintings by Alÿs. Small moments of children in urban and rural landscapes, not always playing but also passing through or working. These postcard-like glimpses act as momentary sketches, but they are not just sketches of the youth within space but the architecture and feel of the space itself, and less about them being in place so much as the situation of people and space creating place.

Most of the films were new productions, though these small painted vignettes are an ongoing exercise by Alÿs as he travels as visual notes, but more sombre and at a smaller-scale they dovetail well with the busy, loud, HD videos filling the main space. A pause away from the energy of youthful expression to pause and consider what is involved in play, not just the personal but also the political, spatial, collaborative, and critical.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

2022’s Biennale has countless works which hit you with their politics. This isn’t always a bad thing, the world is in a place where it needs a jolt to wake up, but there are other strategies for infusing a politic within visual presentation. Here, Alÿs slips it in, secreted behind sheer joy and exuberance. The visitor, lured in by a respite from the Venetian heat and heavy-hitting messages of other works around the Giardini, is invited to step into a world of make believe and escape, and only in dwelling does the deeply rooted situated politics of play become present - unbeknownst perhaps to the children hard at work in their missions, but present in the built and cultural landscapes within which they all take place.

![]()

figs.i-ii

Each video is by Francis Alÿs, the Mexican based Belgian artist with a deep interest in geographic and constructed landscapes, using a range of media to test how geopolitics and social relationships are enacted in place. He frequently uses performance and situated video to explore the human and how it comes up against man-made rules, boundaries, or systems. Here, however, he stays resolutely behind the camera’s lens and simply records and relays the simple act of play.

figs.iii-vi

Within the films, simple and short as they are, there is real human emotion. If play is simply exploratory processes not only of human development, but also learning the rules of societal and spatial engagement, then through these short studies one can see how different cultures or people learn and explore their personal situations, landscapes, and cultures.

A boy struggles with a tyre. Nearly as large as himself, he is pushing it up a hill in a near-Sisyphean task, the ground slag of the Étoile du Congo cobalt mine giving way under his feet as he pushes. The same slag is daily sifted by impromptu and unregulated lithium hunters who search through the poisonous dirt to find a material from which our modern, digitised age relies upon. The boy is rooted in this place, its dust, its new topography, and yet from it find naïve escape – once he gets to the top he squeezes his frame into the tyre and rolls himself down the way he came, eventually collapsing on a side, before starting the process over.

fig.vii

In an entirely different landscape, a girl traverses Hong Kong without stepping on the cracks or joints in the pavement. Her movement across the city turns into a dance, engaging with the landscape in ways seemingly remote and forgotten by the countless adults who look upon her from storefronts, vehicles, and the city beyond her imagination. She chants as she weaves the urban fabric, words from behind her covid mask which help ward off the devil who will commit a crime every time a crack is accidentally stood on. For a while, the city is a place of witchcraft and rhythmic magic, and not of capitalism and grind.

“Step on a line, break the devil’s spine,

Step on a crack, break the devil’s back,

Step in a ditch, your mother’s nose will itch,

But if you step in between, everything will be keen!”

fig.viii

In Mexico, empty and unused homes, perhaps abandoned before construction finished, become a military landscape. Instead of bullets, sharp rays of light shoot across the place, each child holding a fragment of broken mirror and using it as a weapon in a wargame to refract the sun towards the enemy.

The unfinished architecture find a new function, light bullets flashing across façades, the empty rooms offering hiding places and strategic spaces of observation as each side strategically illuminates the other. The architectural ruins here losing their connection to a failed capitalist enterprise, taking on a new meaning projected from childish imagination as the sun is projected across them.

fig.ix

These are landscapes of imagination as much as the physical, illustrated no more than in footage of football in Mosul, Iraq. The two teams do not have a football, and instead perform a consensually imagined match in which an invisible football is passed around, flicked on, tackled for, and saved. A boy flies down the wing, kicking up dust from the gravel road in the shadow of buildings destroyed by war, and he crosses the imaginary ball in hoping for a headed goal. Throughout, there only ever seems to be one ball, the deep concentration into the situation focuses everybody towards a single imagined ball, and through that it becomes real.

The film is interrupted to say that in 2015 the Islamic State publicly executed 13 teenagers for watching football on TV. We return to footage of the game, dusk now setting, and suddenly the play is more serious, the invisibility explained. As the film loops, and the surreal football match is returned to, the humour is less funny, the situation more real.

fig.x

To the side of the central cacophonous space of shouting, screaming, and playful children were two anterooms with small paintings by Alÿs. Small moments of children in urban and rural landscapes, not always playing but also passing through or working. These postcard-like glimpses act as momentary sketches, but they are not just sketches of the youth within space but the architecture and feel of the space itself, and less about them being in place so much as the situation of people and space creating place.

Most of the films were new productions, though these small painted vignettes are an ongoing exercise by Alÿs as he travels as visual notes, but more sombre and at a smaller-scale they dovetail well with the busy, loud, HD videos filling the main space. A pause away from the energy of youthful expression to pause and consider what is involved in play, not just the personal but also the political, spatial, collaborative, and critical.

figs.xi-xiv

2022’s Biennale has countless works which hit you with their politics. This isn’t always a bad thing, the world is in a place where it needs a jolt to wake up, but there are other strategies for infusing a politic within visual presentation. Here, Alÿs slips it in, secreted behind sheer joy and exuberance. The visitor, lured in by a respite from the Venetian heat and heavy-hitting messages of other works around the Giardini, is invited to step into a world of make believe and escape, and only in dwelling does the deeply rooted situated politics of play become present - unbeknownst perhaps to the children hard at work in their missions, but present in the built and cultural landscapes within which they all take place.

fig.xv

Francis Alÿs (Belgium, 1959) lives and works in Mexico City. Trained as an architect, Alÿs’ practice embraces multiple medias, from painting and drawing to video and animation. His works address

ethnological and geopolitical concerns through the observation of and engagement with everyday life.

He has most recently been involved in a series of new projects in Iraq culminating with the historical fiction Sandlines (2018-20). His Children’s Games series (1999- ongoing) is a recollection of scenes of

children at play around the world. A dozen new games filmed in the Democratic Republic of Congo,

Belgium, Canada, Iraq and Hong Kong will be featured at the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Alÿs has exhibited in renowned museums worldwide.

www.francisalys.com

visit

The Nature of the Game, by Francis Alÿs can be visited at the Belgian Pavilion in the Giardini for the 59th International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia until 27 November, 2022.

More information on the Pavilion can be found on the offical website:

www.belgianpavilion.be/nl/projects/belgian-pavilion-2022

images

figs.i,ii The Nature of the Game,

Francis Alÿs.©

Roberto Ruiz

fig.iii Children’s Game #23: Step on a Crack, Hong Kong (2020)

5m.

In collaboration with Félix Blume, Julien Devaux, and Rafael Ortega.© Francis Alÿs, Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Jan Mot & David Zwirner Gallery.

fig.iv Children’s Game #23: Step on a Crack, Hong Kong (2020)

5m.

In collaboration with Félix Blume, Julien Devaux, and Rafael Ortega.

© Francis Alÿs, Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Jan Mot & David Zwirner Gallery.

fig.v Children’s Game #27: Rubi, Tabacongo, DR Congo (2021) 6m18s.

In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Félix Blume.

© Francis Alÿs, Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Jan Mot & David Zwirner Gallery.

fig.vi Children’s Game #31: Slakken (ratio 16:9) Pajottenland, Belgium 2021. 4m59s in collaboration with Julien Devaux and Felix Blume.

© Francis Alÿs, Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Jan Mot & David Zwirner Gallery.

fig.vii Children’s Game #29: Nzango (ratio 4:3) Tabacongo, DR Congo (2021) 5m41s. In collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Julien Devaux and Felix Blume.

© Francis Alÿs, Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Jan Mot & David Zwirner Gallery.

fig.viii Children’s Game #29: La roue, Lubumbashi, DR Congo (2021) 8m43s.

In collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Julien Devaux, and Félix Blume.

© Francis Alÿs, Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Jan Mot & David Zwirner Gallery. Available at: http://francisalys.com/childrens-game-29-la-roue

fig.ix

Children’s Game #23: Step on a Crack, Hong Kong (2020)

5m.

In collaboration with Félix Blume, Julien Devaux, and Rafael Ortega. © Francis Alÿs, Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Jan Mot & David Zwirner Gallery. Available at: http://francisalys.com/childrens-game-23-step-on-a-crack

fig.x Children’s Game #15: Espejos, Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, (2013) 4m53s. In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Felix Blume.

© Francis Alÿs, Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Jan Mot & David Zwirner Gallery. Available at: http://francisalys.com/childrens-game-15-espejos

fig.xi Children’s Game #19: Haram Football, Mosul, Iraq (2017) 9m11s.

In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Félix Blume. © Francis Alÿs, Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Jan Mot & David Zwirner Gallery. Available at: http://francisalys.com/childrens-game-19-haram-football

fig.xii The Nature of the Game, Francis Alÿs.© Roberto Ruiz

fig.xiii Untitled,

Herat, Afghanistan (2012)

Oil on canvas, 13 x 18 cm.

© Francis Alÿs, Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Jan Mot & David Zwirner Gallery.

fig.xiv The Nature of the Game, Francis Alÿs. © Roberto Ruiz

fig.x Untitled,

Bamiyan, Afghanistan (2010)

Oil on canvas, 13 x 18 cm.

© Francis Alÿs, Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Jan Mot & David Zwirner Gallery.

fig.xv The Nature of the Game, Francis Alÿs.© Roberto Ruiz

publication date

25 July 2022

tags

Afghanistan, Francis Alÿs, Belgian Pavilion, Belgium, City, Children, DR Congo, Games, Hong Kong, Iraq, Islamic State, Lithium, Mexico, Play, Painting, Venice, Venice Biennale

More information on the Pavilion can be found on the offical website:

www.belgianpavilion.be/nl/projects/belgian-pavilion-2022