IMAGE CAPITAL: Architectural cameras & photographic values

An exhibition led by photographer Armin Linke and historian Estelle Blaschke looks at the history of photography not with aesthetic consideration, but as a tool of storing & creating value. For recessed.space, Will Jennings visited Fondazione MAST in Bologna to find out more, discovering a deep connection to architectural space along the way.

It is perhaps the most famous architectural photograph ever.

Maybe one of the most famous photographic images made full stop. It is a scene

that captures the modernist age and has been reproduced countless times on anything

from posters to blogs, memes to jigsaws. 260 metres above the streets of

Manhattan, eleven ironworkers casually sit along a narrow iron girder eating

and chatting. Lunch atop a Skyscraper, considered

to have been taken by Charles C. Ebbets, was one of many promotional images

taken in 1932 as publicity for the RCA Building, designed by Raymond Hood.

It's an image so recognisable and renowned that it seems to exist in its own aura, easy to forget that it was in fact produced with a heavy, cumbersome glass plate 5x7 inch large-format camera. Equipment with a great physicality which, along with his heavy carry-case of glass photographic plates, must have presented a task for Ebbets as dangerous as the labour of the anonymous workers on their break.

The skyscraper’s iron geometry isn’t the only architecture entwined with the story of the image. The photograph may have been captured at one of the highest points mankind had built to, the glass plate negative Ebbets made is now located at the other extremity of verticality, in another space of architectural curiosity – 67 metres underground in the Iron Mountain storage facility, Pennsylvania.

![]()

fig.i

When Corbis bought the image as part of the Bettmann Archive collection, the negative was found in a brown enveloped, broken into shards. In an age where images increasingly hold their value – financial or cultural – and meaning digitally, floating around cyberspace and existing in billions of locations simultaneously, instantly extractable from thin air, it’s a reminder of the fragility of the analogue form and the importance of holding onto the originalin whatever form or level of repair it is in.

Photographer Armin Linke found the image in its orange protection case when photographing the Corbis archive securely contained within a refrigerated cave within the Iron Mountain complex, a facility also holding original masters of seminal pop records alongside countless other documents and records of importance within a 158,000 square metre network of spaces in a former limestone mine with armed guards watching over.

Linke’s image of the image is exhibited in the exhibition IMAGE CAPITAL at Fondazione MAST in Bologna, a project he has been developing alongside historian Estelle Blaschke to explore the historic and ongoing process of image making through the consideration of image as a store or tool of value and as a means to access systems of information, as opposed to solely of primary visual importance. It’s an exhibition which mixes Linke’s new photography with archive images and documents in a rich and playful display framing the critical ideas through six categories: memory,access, protection, mining, imaging, and currency.

![]()

![]()

One archive image on display captures the entrance to the mine which now holds Ebbets’ celebrated photograph. Made by an unknown photographer around 1955, the limestone spaces – which had been abandoned as a mine only three years earlier – were then used to store governmental records and patents.

Nearby, a promotional video for the archival programme for open-source software at the GitHub Arctic Code Vault in the Svalbard archipelago played on loop, footage recording an architecture and landscape few will ever experience but is the kind of anonymous, distant spaces of invisible data storage which is deeply enmeshed with our daily lives. Through a car front window, the film records the approach through a snow-filled valley towards the mine entrance, and then takes us on foot into its concealed and protected spaces, before a digital map shows how this discreet location is connected to networks globally.

![]()

fig.iv

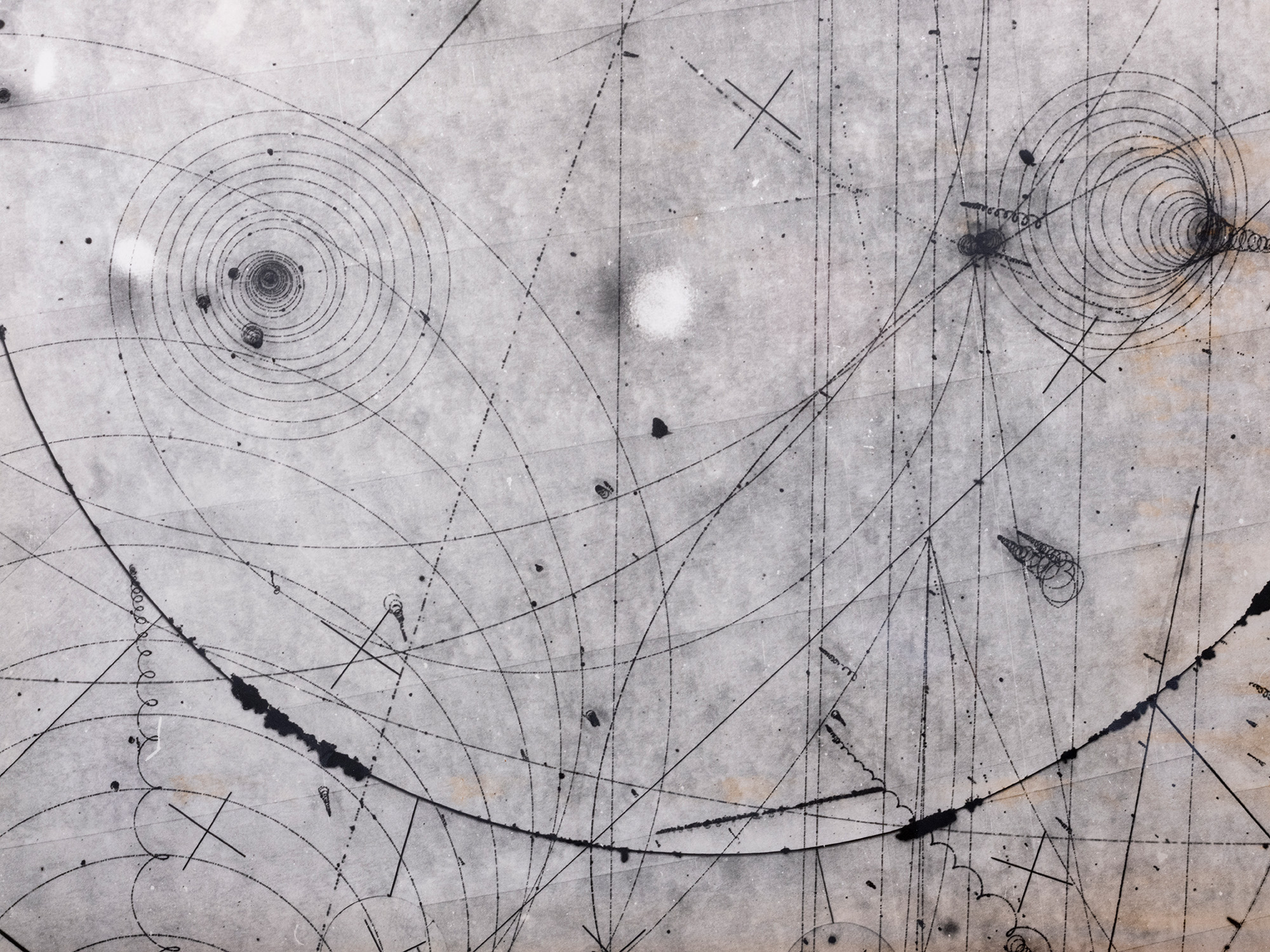

Though the central subject of the image, and its mutability and versatility of function, is rooted lightness and ephemerality – increasingly so in the digital age – there are many moments in the exhibition when physical architecture is central to the image’s existence or means of holding or creating value. Another deeply subterranean architecture documented is CERNs Large Hadron Collider, capturing data from the tiniest events, in the process requiring one of the planet’s largest architectural projects as camera.

![]()

![]()

![]()

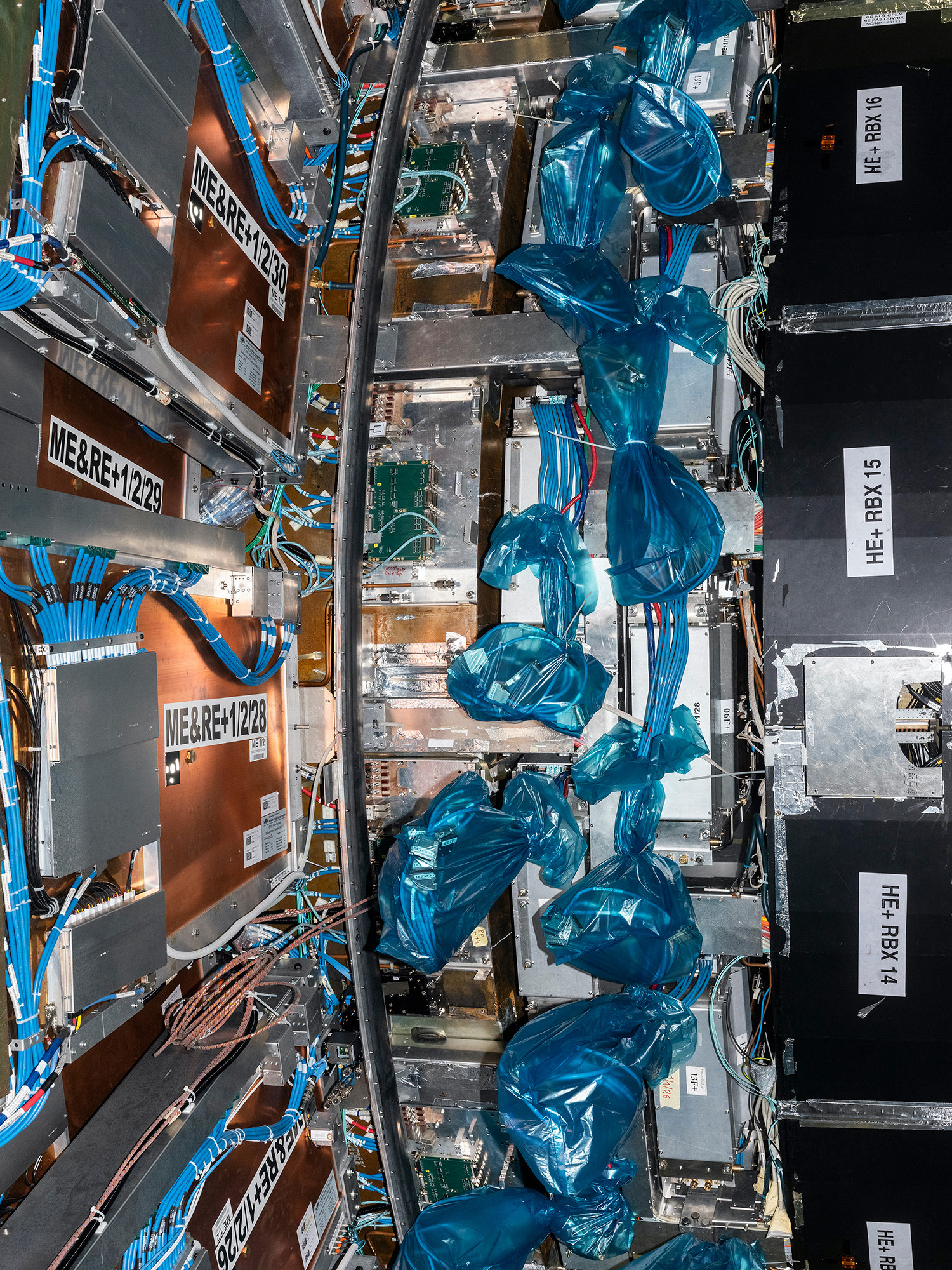

Other artists have visited CERNs spaces and captured its immensity, scale, and sci-fi awe. Linke, however, treats the spaces with a more everyday eye, as a workplace and aesthetically cluttered machine of our age. As a photographer recognising the tool of a trade, he is recording CERNs architectures as components central to the act of image recording, in effect Linke is photographing the inside of a camera, perhaps in the only way a practitioner would recognise.

A closeup of cables may seem uneventful, but it is through these – and millions more – cables that images are being calculated and created which are at the pinnacle of man’s understanding of the world. Yet, the cables and rack they are arranged in are mundane, uneventful as the architectures and places of importance can so often be.

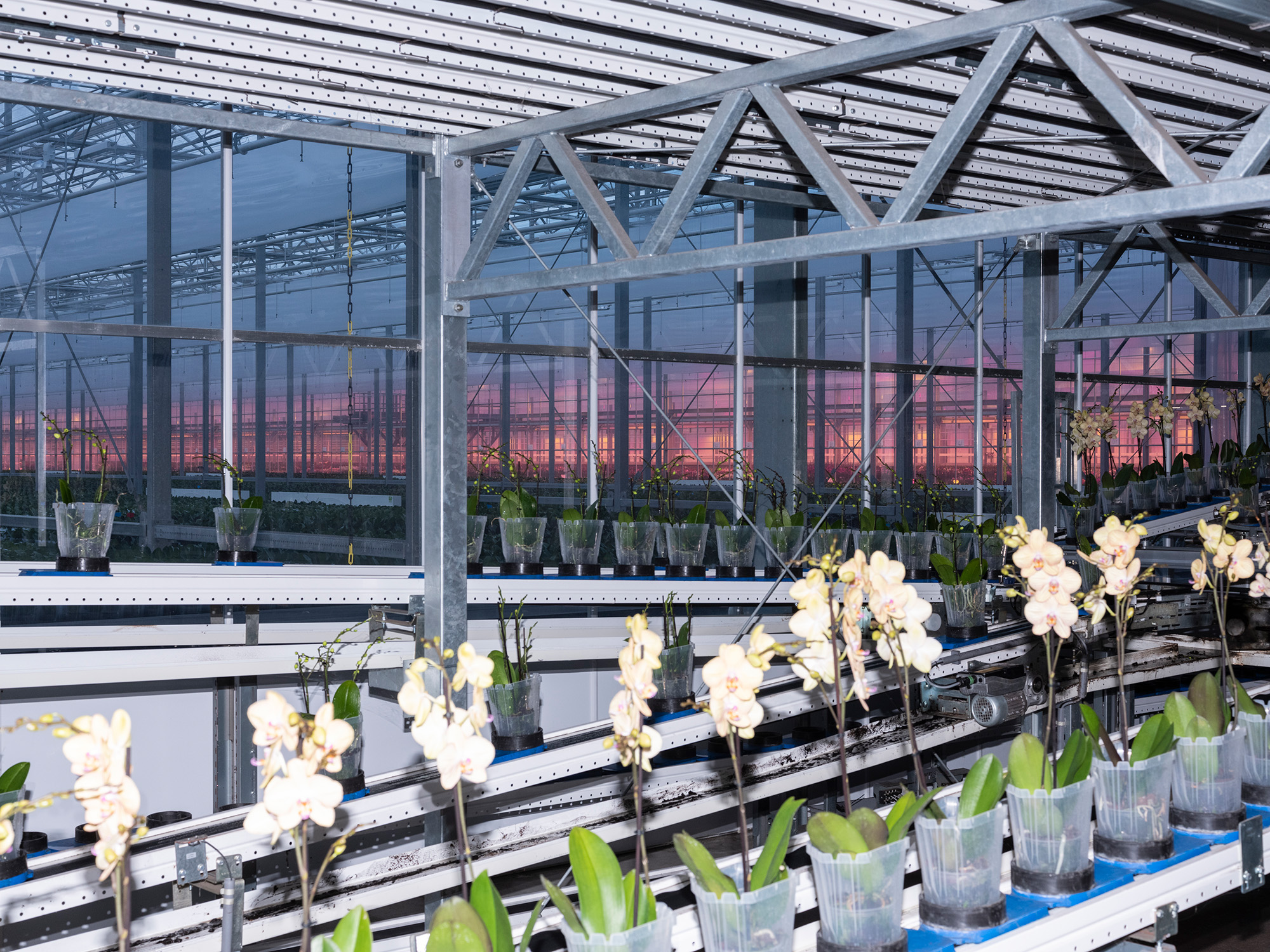

Architecture is a logic system designed for a particular function – whether a that be the cliché machine for living in, or making in, teaching in, or any other programme – the function of a space leads the form, and most architecture has functions for which the form need not be spectacular or even designed to be seen by the public. That doesn’t, however, mean it may not be intriguing, one example is the facilities of Ter Laak Orchids in Wateringen, Netherlands, a company which grows over eight million orchids a year utilising robotic and data processes.

![]()

![]()

As they grow, the orchids are taken on a conveyor belt journey through spaces of various temperatures and past walls which record the minute stages of the plant’s evolution, twenty-four sensors capturing its size, colour, and shape through machine learning algorithms, the captured data is then used to determine the orchid’s final price category and market destination once it has passed through the architectural system.

Blaschke talks says that while like CERN these sensors are not visual cameras, the company terms them as such: “They talk about it as a photo studio – and this is a sort of persistence of photography, which remains in these highly abstract forms of fixing information because here there's no optical system whatsoever, there is no camera, but there is a sensor which records something.”

![]()

fig.x

Also in the Netherlands, the Priva tomato greenhouses similarly capture data from nature’s processes, developing a system they term Plantonomy. From such data they can monetise the growing processes to a greater extent, but the firm also state that the expertise and systems used for such automated cultivation can also be applied to architectural design and building systems management.

Architecture of the future will be automated, and cameras – whether visual or sensor led – will be central to the smartness of the making and operations of such places. The overlap of architecture and visual technology is not new, and while talk today may be focused on metaverses and digital twins, an image in the exhibition touches on how pre-digital technologies formed such an approach to hyperspace.

![]()

fig.xi

A photography from circa 1904 shows Vittore Carpaccio’s Saint Ursula Cycle paintings in situ within the Chapel of Venice’s Scuola di Sant’Orsola. However, in 1808 Carpaccio’s paintings had been removed from the Scuola and later relocated to the Galleria dell’Accademia – and on closer inspection this image is not in fact of a built architecture but a wooden model by art historian Gustav Ludwig of how he believed the paintings to have been displayed. He deployed a mix of model and applied photomontage, which Blaschke suggests “functions like a pre-digital rendering”.

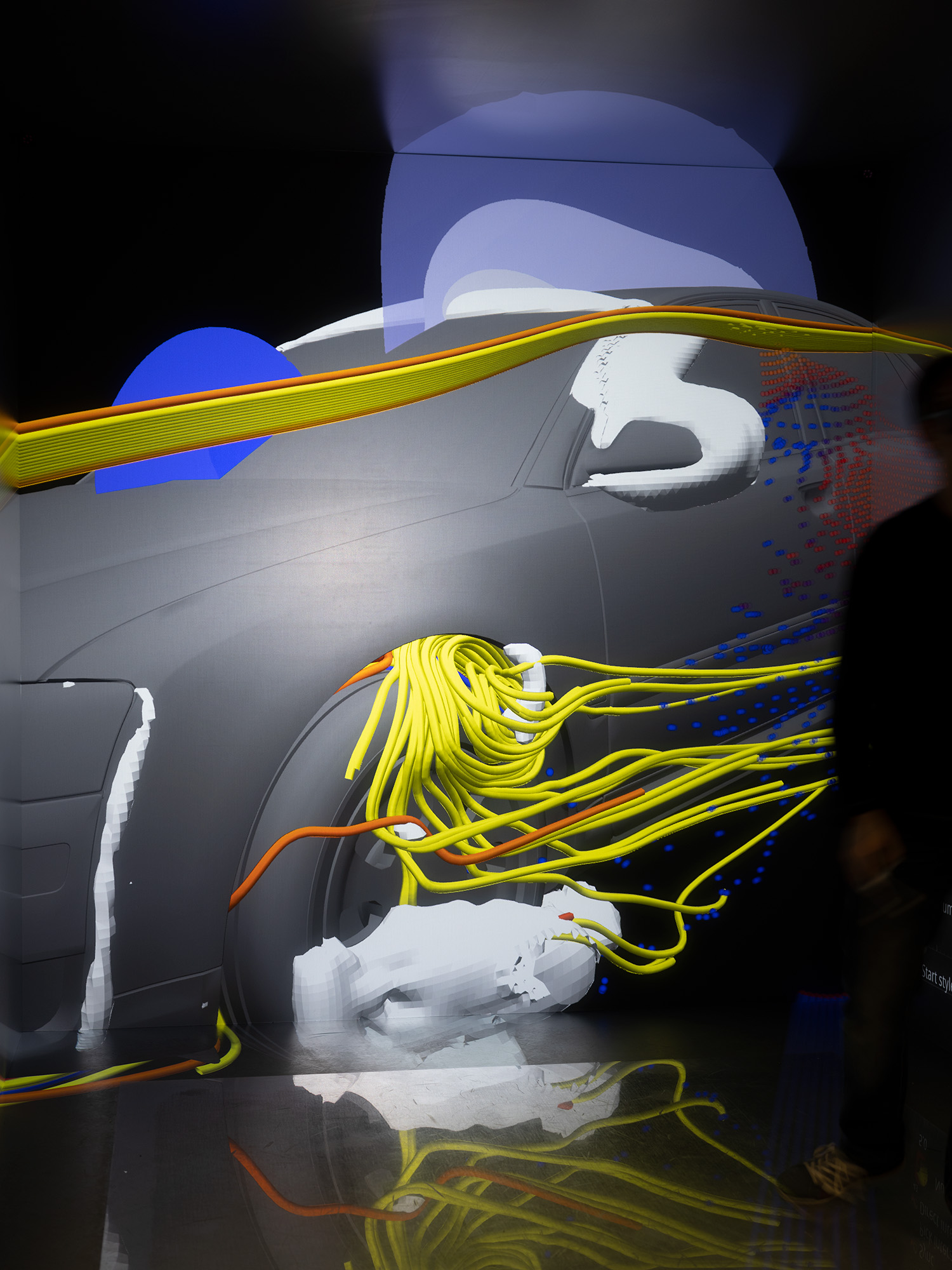

Over a century later, the deployment of digital image making in the design process has gone far further than even hyper-realistic renders. The use of digital model making is covered in the exhibition, focusing on car design – the image below showing development and test phases of airflow over a car in the High-Performance Computing Center at the University of Stuttgart, a digital space where engineers, designers, and marketeers can work together in real time to tweak any desired design. But such photorealistic and immediate calculating and rendering is, and will increasingly be, used throughout architectural design.

![]()

![]()

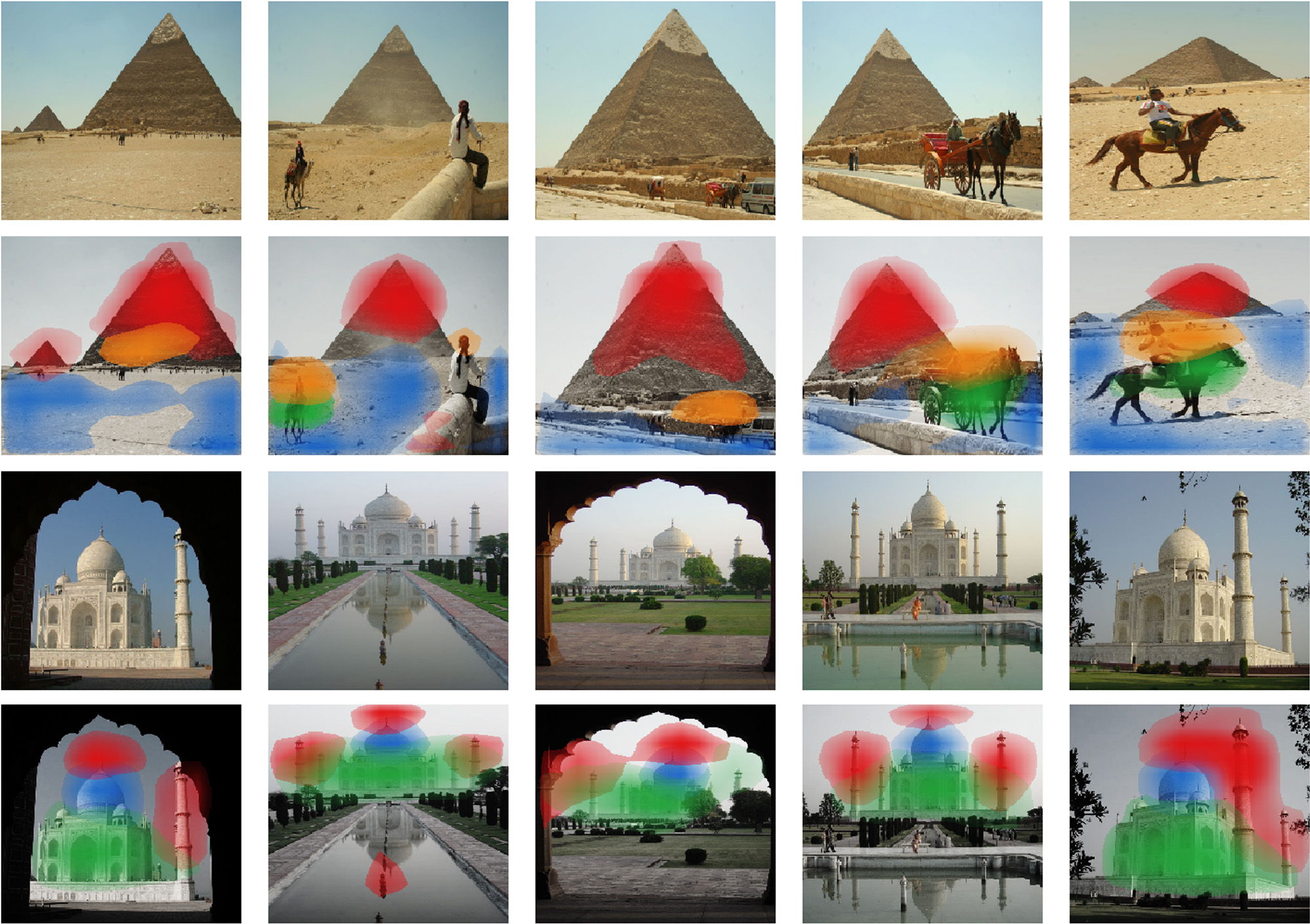

Machine learning is rapidly entwined within such design processes and rendering output. The rise of AI will impact design processes and how we interact with machine tools of design, but even already machine learning can draw huge information from datasets to identify and recognise objects and architectures from various angles. The images above of the Taj Mahal and the Great Pyramid is from a paper presented at the European Conference on Computer Vision, illustrating machine recognition from a variety of angles in order to understand complex human made architectures from whatever angle they are presented.

![]()

![]()

figs.xiv,xv

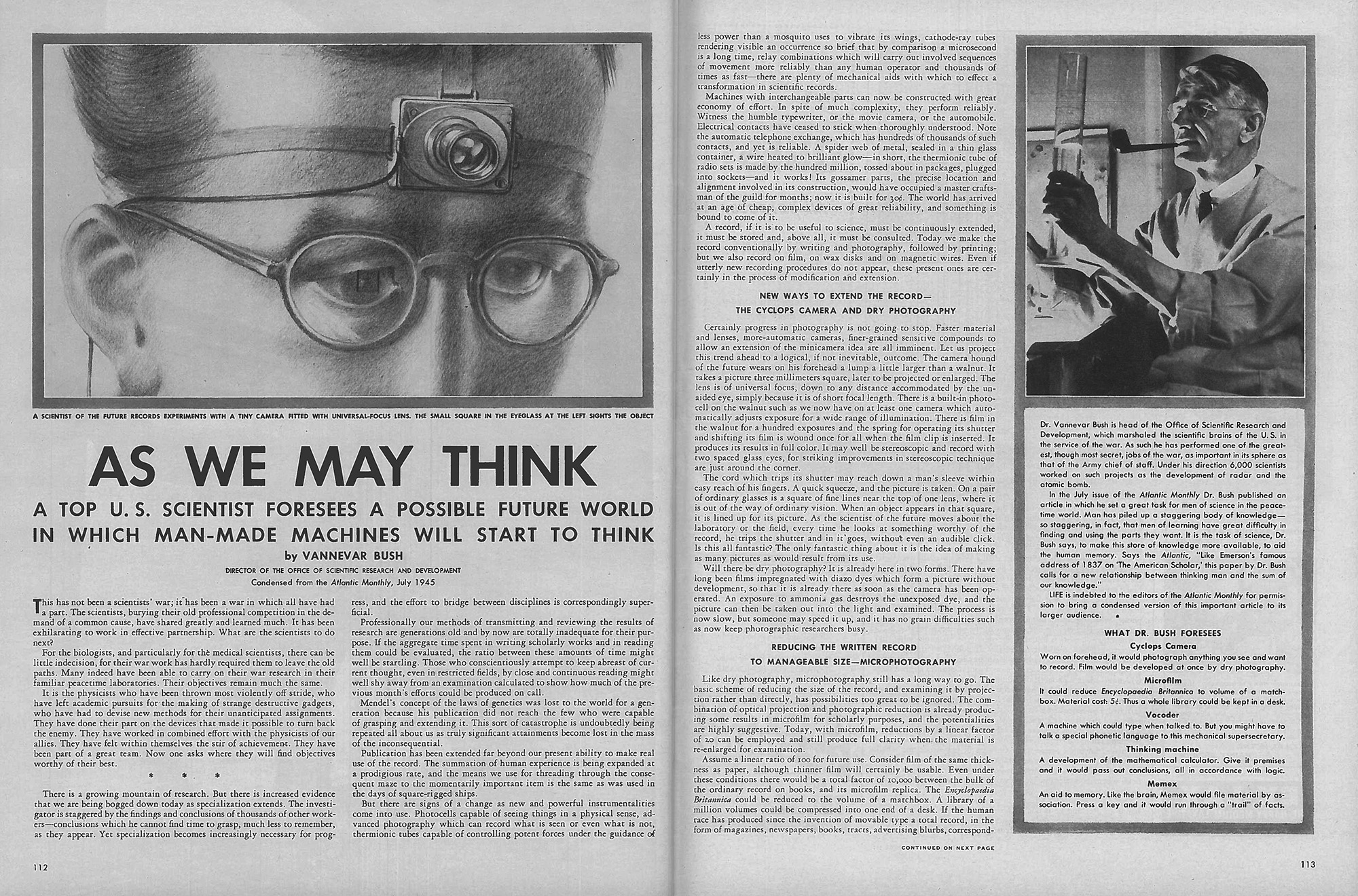

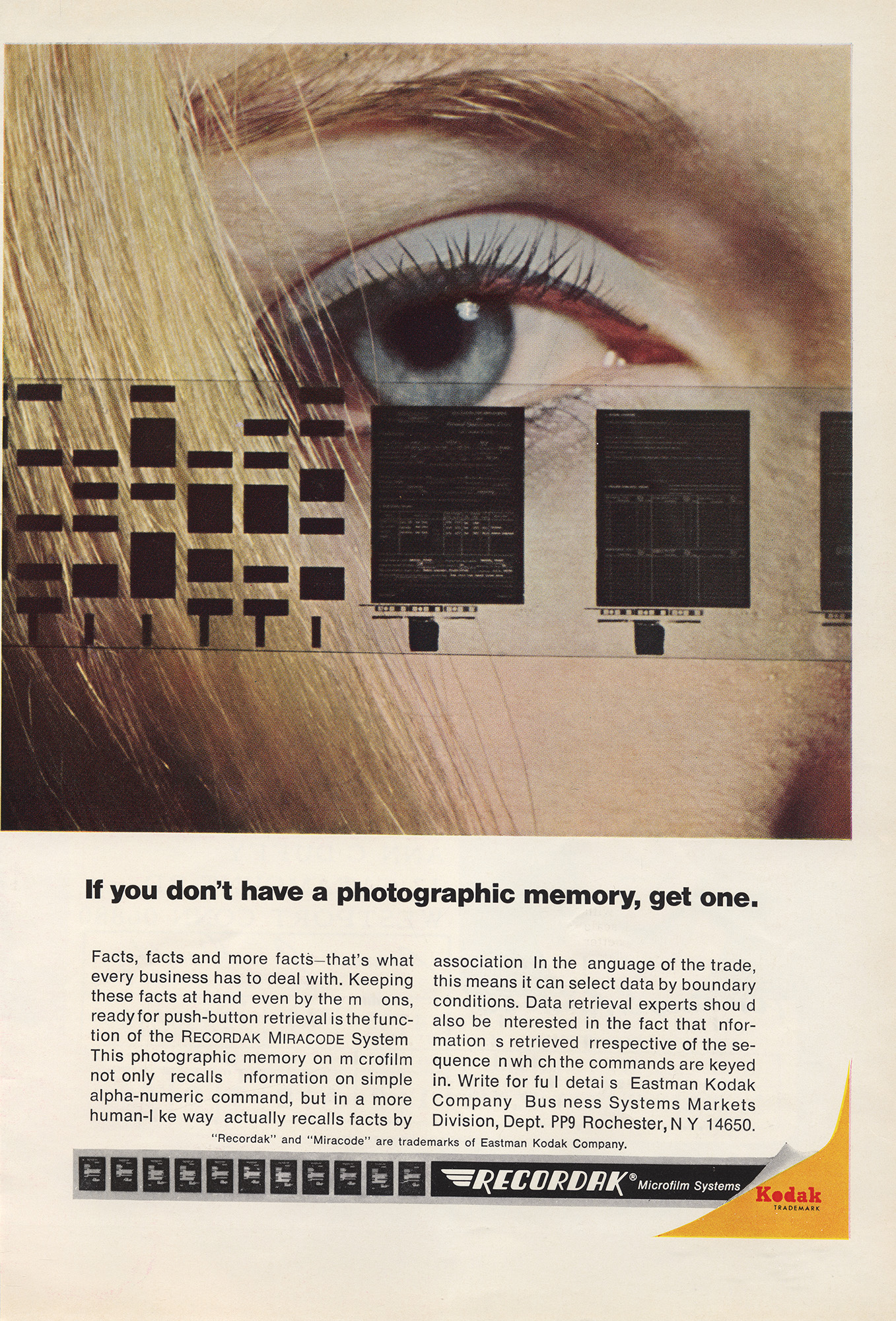

These newly made and historically sourced examples selected by Linke and Blaschke, and curated by Francesco Zanot ( in both exhibition and the freely accessible Online Publication) show that this evolution is not as sudden as you may think – a 1945 Life Magazine article discussing “a future world in which man-made machines will start to think” and a 1966 advert for Kodak’s Miracode System of image-based data storage show that technology and use of images as processes for containing or generating value – aside from any visual quality they may carry – carries throughout the history of photography.

Throughout that history, architecture has not only been a critical element of the storage, conservation, and display of such imagery, but often and increasingly an extension of the camera itself. As surveillance systems embed into Smart Cities, as greenhouses capture data of conveyed plants, as experiments such as CERN became an architecture solely shaped around the recording of the most revealing of images, the conflation of data capture and place design will only become more compressed – and in designing that compression, architects should always question what value is being captured, and who values most from it.

It's an image so recognisable and renowned that it seems to exist in its own aura, easy to forget that it was in fact produced with a heavy, cumbersome glass plate 5x7 inch large-format camera. Equipment with a great physicality which, along with his heavy carry-case of glass photographic plates, must have presented a task for Ebbets as dangerous as the labour of the anonymous workers on their break.

The skyscraper’s iron geometry isn’t the only architecture entwined with the story of the image. The photograph may have been captured at one of the highest points mankind had built to, the glass plate negative Ebbets made is now located at the other extremity of verticality, in another space of architectural curiosity – 67 metres underground in the Iron Mountain storage facility, Pennsylvania.

fig.i

When Corbis bought the image as part of the Bettmann Archive collection, the negative was found in a brown enveloped, broken into shards. In an age where images increasingly hold their value – financial or cultural – and meaning digitally, floating around cyberspace and existing in billions of locations simultaneously, instantly extractable from thin air, it’s a reminder of the fragility of the analogue form and the importance of holding onto the originalin whatever form or level of repair it is in.

Photographer Armin Linke found the image in its orange protection case when photographing the Corbis archive securely contained within a refrigerated cave within the Iron Mountain complex, a facility also holding original masters of seminal pop records alongside countless other documents and records of importance within a 158,000 square metre network of spaces in a former limestone mine with armed guards watching over.

Linke’s image of the image is exhibited in the exhibition IMAGE CAPITAL at Fondazione MAST in Bologna, a project he has been developing alongside historian Estelle Blaschke to explore the historic and ongoing process of image making through the consideration of image as a store or tool of value and as a means to access systems of information, as opposed to solely of primary visual importance. It’s an exhibition which mixes Linke’s new photography with archive images and documents in a rich and playful display framing the critical ideas through six categories: memory,access, protection, mining, imaging, and currency.

figs.ii,iii

One archive image on display captures the entrance to the mine which now holds Ebbets’ celebrated photograph. Made by an unknown photographer around 1955, the limestone spaces – which had been abandoned as a mine only three years earlier – were then used to store governmental records and patents.

Nearby, a promotional video for the archival programme for open-source software at the GitHub Arctic Code Vault in the Svalbard archipelago played on loop, footage recording an architecture and landscape few will ever experience but is the kind of anonymous, distant spaces of invisible data storage which is deeply enmeshed with our daily lives. Through a car front window, the film records the approach through a snow-filled valley towards the mine entrance, and then takes us on foot into its concealed and protected spaces, before a digital map shows how this discreet location is connected to networks globally.

fig.iv

Though the central subject of the image, and its mutability and versatility of function, is rooted lightness and ephemerality – increasingly so in the digital age – there are many moments in the exhibition when physical architecture is central to the image’s existence or means of holding or creating value. Another deeply subterranean architecture documented is CERNs Large Hadron Collider, capturing data from the tiniest events, in the process requiring one of the planet’s largest architectural projects as camera.

figs.v-vii

Other artists have visited CERNs spaces and captured its immensity, scale, and sci-fi awe. Linke, however, treats the spaces with a more everyday eye, as a workplace and aesthetically cluttered machine of our age. As a photographer recognising the tool of a trade, he is recording CERNs architectures as components central to the act of image recording, in effect Linke is photographing the inside of a camera, perhaps in the only way a practitioner would recognise.

A closeup of cables may seem uneventful, but it is through these – and millions more – cables that images are being calculated and created which are at the pinnacle of man’s understanding of the world. Yet, the cables and rack they are arranged in are mundane, uneventful as the architectures and places of importance can so often be.

Architecture is a logic system designed for a particular function – whether a that be the cliché machine for living in, or making in, teaching in, or any other programme – the function of a space leads the form, and most architecture has functions for which the form need not be spectacular or even designed to be seen by the public. That doesn’t, however, mean it may not be intriguing, one example is the facilities of Ter Laak Orchids in Wateringen, Netherlands, a company which grows over eight million orchids a year utilising robotic and data processes.

figs.viii,ix

As they grow, the orchids are taken on a conveyor belt journey through spaces of various temperatures and past walls which record the minute stages of the plant’s evolution, twenty-four sensors capturing its size, colour, and shape through machine learning algorithms, the captured data is then used to determine the orchid’s final price category and market destination once it has passed through the architectural system.

Blaschke talks says that while like CERN these sensors are not visual cameras, the company terms them as such: “They talk about it as a photo studio – and this is a sort of persistence of photography, which remains in these highly abstract forms of fixing information because here there's no optical system whatsoever, there is no camera, but there is a sensor which records something.”

fig.x

Also in the Netherlands, the Priva tomato greenhouses similarly capture data from nature’s processes, developing a system they term Plantonomy. From such data they can monetise the growing processes to a greater extent, but the firm also state that the expertise and systems used for such automated cultivation can also be applied to architectural design and building systems management.

Architecture of the future will be automated, and cameras – whether visual or sensor led – will be central to the smartness of the making and operations of such places. The overlap of architecture and visual technology is not new, and while talk today may be focused on metaverses and digital twins, an image in the exhibition touches on how pre-digital technologies formed such an approach to hyperspace.

fig.xi

A photography from circa 1904 shows Vittore Carpaccio’s Saint Ursula Cycle paintings in situ within the Chapel of Venice’s Scuola di Sant’Orsola. However, in 1808 Carpaccio’s paintings had been removed from the Scuola and later relocated to the Galleria dell’Accademia – and on closer inspection this image is not in fact of a built architecture but a wooden model by art historian Gustav Ludwig of how he believed the paintings to have been displayed. He deployed a mix of model and applied photomontage, which Blaschke suggests “functions like a pre-digital rendering”.

Over a century later, the deployment of digital image making in the design process has gone far further than even hyper-realistic renders. The use of digital model making is covered in the exhibition, focusing on car design – the image below showing development and test phases of airflow over a car in the High-Performance Computing Center at the University of Stuttgart, a digital space where engineers, designers, and marketeers can work together in real time to tweak any desired design. But such photorealistic and immediate calculating and rendering is, and will increasingly be, used throughout architectural design.

figs.xii,xiii

Machine learning is rapidly entwined within such design processes and rendering output. The rise of AI will impact design processes and how we interact with machine tools of design, but even already machine learning can draw huge information from datasets to identify and recognise objects and architectures from various angles. The images above of the Taj Mahal and the Great Pyramid is from a paper presented at the European Conference on Computer Vision, illustrating machine recognition from a variety of angles in order to understand complex human made architectures from whatever angle they are presented.

figs.xiv,xv

These newly made and historically sourced examples selected by Linke and Blaschke, and curated by Francesco Zanot ( in both exhibition and the freely accessible Online Publication) show that this evolution is not as sudden as you may think – a 1945 Life Magazine article discussing “a future world in which man-made machines will start to think” and a 1966 advert for Kodak’s Miracode System of image-based data storage show that technology and use of images as processes for containing or generating value – aside from any visual quality they may carry – carries throughout the history of photography.

Throughout that history, architecture has not only been a critical element of the storage, conservation, and display of such imagery, but often and increasingly an extension of the camera itself. As surveillance systems embed into Smart Cities, as greenhouses capture data of conveyed plants, as experiments such as CERN became an architecture solely shaped around the recording of the most revealing of images, the conflation of data capture and place design will only become more compressed – and in designing that compression, architects should always question what value is being captured, and who values most from it.

Armin Linke (b. 1966, Milan) is an artist

working with photography by setting up processes that question the medium, its

technologies, narrative structures, and complicities within wider

socio-political structures. Linke’s work observes how human beings (re-)design

and use space and time as social forms: it constructs questions / propositions

on planning the future, on the hidden entanglements and inter-dependences

within the human and other-than collective design practices, and the shifting

of sites of responsibility. Former MIT Visual Arts Program research affiliate,

guest professor at the IUAV Arts and Design University in Venice, and professor

of photography at the Karlsruhe University for Arts and Design, Linke is

currently a guest professor at ISIA, Urbino, artist in residence at the KHI

Florenz, and guest artist at the CERN Geneva.

www.arminlinke.com

Estelle Blaschke is a photography

historian. She holds an interim professorship in Media Studies at the

University of Basel and teaches photography history and theory at ECAL. Her

research focuses on the theory of photographic archives, the circulation of

images, image infrastructures and the history of digital photography. Her

research focuses on the theory of photographic archives, the circulation of

images, image infrastructures and the history of digital photography. She is

the author of the book Banking on Images: The

Bettmann Archive and Corbis (Spector Books,

2016) and a member of the editorial board of the scientific journal Transbordeur.

Photographie, Histoire, Société. In 2019, she

edited the Photographie et technologies de

l’information (Transbordeur no.3), together with Davide

Nerini. With Armin Linke, she directs the research and exhibition project IMAGE

CAPITAL.

www.estelleblaschke.net

Francesco Zanot is a photography curator,

teacher and writer. Founding curator at Camera (the Italian Centre for

Photography, Turin) from 2015-18, he has worked on exhibitions and publications

with and about many Italian and international photographers, such as Boris

Mikhailov, Carlo Mollino, Francesco Jodice, Takashi Homma, Erik Kessels, and

Luigi Ghirri. His essays have been published in monographs on the work of

numerous artists worldwide, and together with Alec Soth, he is the author of

the book Ping Pong Conversations.

Director of the Master in Photography and Visual Design organised by NABA in

Milan, he gave classes and seminars in many academic institutions, such as the

Columbia University in New York, ECAL in Lausanne, UPV in Valencia and IUAV in

Venice. He curated the inaugural exhibitions Give Me

Yesterday and Stefano Graziani:

Questioning Pictures, at Fondazione Prada Osservatorio, Milan.

He’s currently artistic director of the Foto/Industria Biennale at MAST,

Bologna.

Fondazione MAST is an

international cultural and philanthropic institution that focuses on art,

technology and innovation. Coesia Holding, the global leaders in industrial and

packaging solutions based on technological innovation, opened MAST (which

stands for Manufacture, Art, Experimentation and Technology in Italian) in 2013

next to its factories in Bologna, as a place to celebrate culture and its

workers. The MAST Foundation’s mission is to be an open area in which every

citizen has access to learning, the arts and photography on the world of

labour, to be a stimulating and inviting cultural destination that promotes

personal growth and well-being. With spaces and services dedicated solely to

the enrichment of company employees, MAST also welcomes the world with its

extraordinary exhibitions and public programmes, always free of charge.

www.mast.org

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.estelleblaschke.net

Francesco Zanot is a photography curator, teacher and writer. Founding curator at Camera (the Italian Centre for Photography, Turin) from 2015-18, he has worked on exhibitions and publications with and about many Italian and international photographers, such as Boris Mikhailov, Carlo Mollino, Francesco Jodice, Takashi Homma, Erik Kessels, and Luigi Ghirri. His essays have been published in monographs on the work of numerous artists worldwide, and together with Alec Soth, he is the author of the book Ping Pong Conversations. Director of the Master in Photography and Visual Design organised by NABA in Milan, he gave classes and seminars in many academic institutions, such as the Columbia University in New York, ECAL in Lausanne, UPV in Valencia and IUAV in Venice. He curated the inaugural exhibitions Give Me Yesterday and Stefano Graziani: Questioning Pictures, at Fondazione Prada Osservatorio, Milan. He’s currently artistic director of the Foto/Industria Biennale at MAST, Bologna.

Fondazione MAST is an international cultural and philanthropic institution that focuses on art, technology and innovation. Coesia Holding, the global leaders in industrial and packaging solutions based on technological innovation, opened MAST (which stands for Manufacture, Art, Experimentation and Technology in Italian) in 2013 next to its factories in Bologna, as a place to celebrate culture and its workers. The MAST Foundation’s mission is to be an open area in which every citizen has access to learning, the arts and photography on the world of labour, to be a stimulating and inviting cultural destination that promotes personal growth and well-being. With spaces and services dedicated solely to the enrichment of company employees, MAST also welcomes the world with its extraordinary exhibitions and public programmes, always free of charge.

www.mast.org

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

visit

You can visit IMAGE CAPITAL at Fondazione MAST, Bologna, until 08 January 2023:

www.mast.org/image-capital

A second version of the exhibition is also showing at Museum Folkwang, Essen, until 11 December 2022:

www.museum-folkwang.de/en/exhibition/image-capital

In 2023 an evolution of the exhibition will be on display at Center Pompidou, Paris & the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation, Frankfurt /

Eschborn.

The online publication of IMAGE CAPITAL can be visited at:

www.image-capital.com

images

fig.i Armin Linke, Iron Mountain preservation facility, Boyers (PA), USA, 2018.

fig.ii University of Rochester, Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP), Kodak Historical Collection. Photographer unknown, entrance to the Iron Mountain preservation facility at Boyers (PA), ca.

fig.iii Armin Linke, Iron Mountain preservation facility, Boyers (PA), USA, 2018.

fig.iv University of Rochester, Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP), Kodak Historical Collection. Photographer unknown, Recordak underground vault at the Iron Mountain, Boyers (PA), 1964.

fig.v Armin Linke, CERN, Large Hadron Collider (LHC), cabling, Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

fig.vi Armin Linke, CERN, Large Hadron Collider (LHC), cabling, Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

fig.vii Events of particle tracks in experiment LEBC, LExan Bubble Chamber, installed in the North Area of the Super Proton Synchrotron accelerator, 09.12.1981, CERN, Geneva, Switzerland.

fig.viii Armin Linke, Ter Laak Orchids, orchid production line, Wateringen, Netherlands, 2021.

fig.ix Armin Linke, Ter Laak Orchids, camera sorting technology, Wateringen, Netherlands, 2021.

fig.x

Armin Linke, Priva, tomato greenhouse, Priva Campus, De Lier, Netherlands, 2021.

fig.xi Gustav Ludwig’s reconstruction of Carpaccio’s Saint Ursula Cycle, wooden model with photomontage, ca. 1904. Photo Library of the Kunsthistorisches Institut – Max-Planck-Institut, Florence, Italy.

fig.xii University of Stuttgart, High-Performance Computing Center (HLRS), Stuttgart, Germany, 2019.

fig.xiii Edo Collins, Radhakrishna Achanta, Sabine Süsstrunk, Deep Feature Factorization for Concept Discovery, paper presented at the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 2018.

fig.xiv Vannevar Bush, As We May Think: A top U.S. scientist foresees a possible future world in which man-made machines will start to think, in Life Magazine, vol. 19, September 1945, pp. 112–113.

fig.xv George Eastman House, the Legacy Collection. Kodak ad for the Recordak Miracode System, 1966.

publication date

11 November 2022

tags

AI, Artificial intelligence, Bettmann Archive, Estelle Blaschke, Camera, Capital, Cars, Carpaccio, CERN, Centre Pompidou, Corbis, Data, Data storage, Deutsche Börse, Charles Ebbets, Ephemerality, Museum Folkwang, Github, Github Arctic Code Vault, Will Jennings, Gustav Ludwig, Iron Mountain, Life Magazine, Armin Linke, Lunch atop a skyscraper, Machine learning, Fondazione MAST, Memory, Mining, Photography, Plantonomy, Pyramids, Saint Ursula Cycle, Science, Scuola di Sant Orsola, Skyscraper, Smart City, Storage, Surveillance, Taj Mahal, Tar Laak Orchids, Technology, Value, Francesco Zanot

www.mast.org/image-capital

A second version of the exhibition is also showing at Museum Folkwang, Essen, until 11 December 2022:

www.museum-folkwang.de/en/exhibition/image-capital

In 2023 an evolution of the exhibition will be on display at Center Pompidou, Paris & the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation, Frankfurt / Eschborn.

The online publication of IMAGE CAPITAL can be visited at:

www.image-capital.com