Maurice Broomfield’s Industrial Sublime: in conversation with Martin Barnes

Maurice Broomfield

(1916-2010) spent his career capturing the awe and beauty of vast – & often hostile – architectural spaces, creating images from the 1940s to 60s which

celebrate the architecture of manufacturing and industry & those who worked within. Predominantly on commission from factories for promotions & trade

brochures, his works were also printed at a larger scale and presented as

artworks. Awe-inspiring & intriguing, Broomfield’s photographs reveal architecturally complex buildings that tower over their occupants at a unique moment in British history. For recessed.space Lara Chapman spoke to Martin Barnes of the V&A

Museum about Broomfield’s work, & his relationship to architecture & workers.

In the recent

Victoria & Albert Museum exhibition (and book of the same name) Industrial Sublime: Maurice Broomfield,

Senior Curator of photography Martin Barnes started a project to reconsider and

bring light to the archive of a photographer whose work intersects

architecture, industry, and fine art. Barnes first met Broomfield 15 years ago,

going on to acquire the photographer’s archive for the museum. After working to

preserve decaying negatives and store the archive safely, Barnes has spent the

last seven years digging into the material, beginning to draw out its most

spectacular images and tracing where they were published.

![]()

fig.i

Lara Chapman: How did you begin to research and understand Maurice Broomfield’s work?

Martin Barnes: It has been a long journey. I met Maurice nearly 15 years ago when I was introduced to him by a documentary filmmaker. I then interviewed him for the British Library’s National Sound Archive which has a collection of audio life story interviews. I thought he’d be an interesting person to interview, not least because he had been alive for most of the 20th century and had a fascinating life story.

I gradually began to understand that he still had the archive of his photography business in his house. When he worked for companies throughout Britain, across Europe and in other places he kept the copyrights, the negatives, and the contact prints. It was quite remarkable that there was this large survival of a working photographer’s commercial practice and an archive that hadn’t been dispersed to different companies.

![]()

What value did you see in the archive and why did you want to acquire it for the V&A’s collection?

It seemed like such an important slice of history on many levels – social history, British history, industrial history, and the history of Maurice’s work as a spectacular image maker. It also corresponded to other areas of the V&A’s interests like architecture, the production of glass, steel, ceramics and other things that we collect which were often produced in those same factories that he photographed. It seemed obvious to bring that archive into the museum and to preserve it.

What is in the archive?

The bulk of the archive is negatives and contact prints. There are about 30,000 negatives. Most of which were made over a period of about 25 years. Then, there are all his business ledgers, press clippings, an archive of trade journals and magazines that he’d illustrated and, finally, some beautiful exhibition prints. It was really fascinating to dig into the survival of this archive and to see how he had repurposed different images and how they had been used.

The exhibition and the book are a first pass at going through the huge archive to draw out some of the more spectacular images of the factories and particularly around British industry.

![]()

It’s amazing that the archive is so massive! In the exhibition I was intrigued that his working shots and artistic shots were often the same image. When a photograph is in a brochure or pamphlet, it is still amazing, but because of the context also somewhat unremarkable. If I hadn’t been looking at them in an exhibition context, I probably wouldn’t have given them a second thought, but when the same image is blown up, it is incredible how much it transforms. How do you think that showing photographs as artworks rather than documentary changes them? Does this create tension in his work?

That is precisely what I wanted to highlight in the exhibition. There is a backbone down the middle of the exhibition made up of display cases. In them, you have the original trade publications, company reports, statistical reports, brochures, and company manifestos. Most of those images were produced based on a commission.

I wanted to trace where the same image had appeared, say in a commissioned piece by an industrial company which would have been the original context and then in a photography magazine which is demonstrating technical abilities with colour film or black and white printing. And then the same image might have been reproduced in the Financial Times as documentation of Britain’s productivity and used as a kind of propaganda about British industry, and then he would print the exhibition large-scale for the Royal Photographic Society or to tour in an exhibition for example.

After he’d retired and almost given up on a career as a photographer in the 90s, he revisited his own archive and selected images that he felt were the most artistic to reprint. There is a set of images that Maurice himself revisited and understood still in a slightly different way, no longer needing to satisfy a brief or a client.

![]()

How did he manage to make images that worked across so many different types of publications and impart so many different meanings and messages?

I think he felt like the factory was like a stage set. He could produce his vision and enjoy the visual spectacle of the industry whilst knowing that he could also satisfy a brief for a client. It is all about context really – there was a clever repurposing of the image at different scales, sometimes in colour, sometimes black and white, sometimes in newsprint, and sometimes as a beautifully printed image. I think he was good at picking very graphic contrasting images which would reproduce at a small scale and a very large scale and still hold up.

Often, within two or three years of making a series of images, Maurice might select one photograph from an entire shoot – say Ford or the British Nylon Spinners or English Electric – and then make it into very large print, nearly a metre or metre-an-a-half in scale for an exhibition and take it out of context of the trade reports. Then, you don’t see any sequence of production, surrounding architecture or anything that explains what this single spectacular image is. If you have no context for the industry, you are often left wondering what is being depicted.

![]()

What do you think the effect of removing the context was?

He was very aware that he was making quite surreal images and that by taking them out of context he understood that they could be read in a way that, divorced from their context, they are just a spectacular image. A lot of his reference points were things like Joseph Wright of Darby’s paintings where, without the title, you don’t know what the experiment being shown in the painting is. They both rely on that visual spectacle to start with.

It is a unique way of looking at a factory setting which, I imagine, was quite a hostile space. Going back to this idea of the factory as a stage set, it is interesting in the sense that the images look very natural but are actually manufactured.

A lot of the photographs were based on his initial visits to the factories. Sometimes he’d turn up the day before without any camera and just walk around the factory, getting to know the people, chatting, making pencil sketches, and noticing the way someone was standing or the quality of light with a particular machine or coming through a window or something.

He would then return with that knowledge of what it was like but then he’d amplify the scene with powerful lighting or by getting somebody to pose in a position he’d seen them the day before at work. So they are kind of performing their own job. It is a bit like reality TV which isn’t really real, but set up based on a trope of what you might see. He described it as unashamedly using the factory like a stage set and that he was the director of this play with actors who were like a cast of real characters. But he might move them around the factory or ask somebody else to stand in for somebody who was doing the job but who he thought was more photogenic. There is quite a lot of manipulation behind what appears to be an authentic, documentary image.

![]()

And yet, they do document a unique time in British manufacturing history. Looking back on these photos, with the perspective of a few decades, what do you think Broomfield’s photographs can teach us about the world today?

I think over the last ten years the photographs have been repurposed and we can understand them differently – in ways that Maurice might not have originally intended. The images gain new meanings over time. His pictures were originally about celebrating industry and progress and technology, intended as a public exercise in post-war productivity. Maurice was unashamed about being part of that reconstructive effort to show Britain, and particularly British factories, as capable and technologically advanced. Then, at one stage, they became about the decline of industry and the nostalgia for a loss of the technical skill, ingenuity, and high productivity of the post-war period.

In the last five to ten years, those pictures have been read around climate anxiety and crisis, and alternative form of energy and pollution. They occupy this really interesting territory where you look at them and you feel maybe simultaneously nostalgic or impressed and then you question the toxic legacy of the industry that you are seeing depicted. You’re left wondering what position the photographer occupied historically. Is it critical? Is it celebratory?

Photographs of oil rigs in the North Sea, for example, make you now think about the toxic legacy of the oil industry. The images become topical again in different ways, in different decades but because they are initially very gripping and spectacular, you are drawn into them. They have beauty and fear in them which is, again, like an eighteenth-century idea of sublime and terror and beauty mixed. That is very potent.

![]()

Yes, I think it comes back to this idea of context again which, I supposed runs through a lot of photography. This is more about the context of where you look at an image from and what position you have…

Yes, I think with any photography, the further away that you get from the moment the picture was produced, the more meaning it can hold. Certain images or certain photographers' works seem to get reinterpreted for the current generation and hold different meanings. Their critical fortunes can go up and down depending on how relevant they are for the particular generation. Maurice’s pictures seem to have survived in different contexts in very powerful ways. That’s partly because they are so artfully made. The craft of the images in the first place is so good that it just has an instant visual route into them.

![]()

Do you think photographers are working in a similar way to Broomfield today, in that they are capturing industrial landscapes with these ideas of awe and the sublime, but maybe from a more critical perspective?

Yes, I think the idea of the beauty of industrial devastation as a way of drawing you in is well-worn by now. I think the key figure is Edward Burtynsky. It’s using that initial beauty and then you realise the photo is of a toxic slick or a polluted lake, but the colours are so amazing. That tradition now is quite strong in photography.

I guess that Maurice is coming at it from a different angle. He wasn’t consciously making beautiful images which are visually seductive of things that he knew were devastating and needed to be highlighted. That is not where he is coming from in making those images. That is how we read them today.

The complexity of them is that he admired the workers. He came from a background in factories, working for Rolls Royce as a young man. They hold this ambiguity in his admiration for skill and craft and ingenuity and it puts you, as a viewer, in quite a complex position, I think.

![]()

Using this tradition of sublime industrial devastation comes with a tricky conflict – there is a question of whether we should be making such awful things look so beautiful. On one hand, there is a need to draw people in and to make them pay attention to environmentally damaging spaces, but there is a risk that viewers may feel pacified to the dangers through images so beautiful and amazing. Broomfield’s intention was different, he was trying to celebrate the beauty of the industrial – it feels as if the viewers’ feelings and photographer’s intentions are more aligned.

In his work, there was very little critical perspective on industry. Speaking to him, he came from a very squarely humanist, pacifist position. He was a tremendous optimist. He wanted to be helpful. He had witnessed the devastation of the Second World War and drove an ambulance during the Blitz, he was a very conscientious objector and was involved in repatriation in the war effort. For somebody of that generation, all his ambition was to rebuild the country.

He put his eggs in the basket of technology by building positive imagery of expert technological advancement and celebrating that work. That was the side he was on. He wasn’t investigative, he was working for a client and wanted to make a positive vision of industrial manufacturing. He liked the ingenuity of it, he thought it was beautiful. It is only retrospectively that we see what difficult legacies some of those things have.

![]()

It strikes me that all the renewable and green energy innovations that are trying to gain traction today need a photographer like Broomfield to show them as amazing spaces of knowledge and industry and scale and skill. To celebrate what is happening and to show what is possible – it might help them gain more support perhaps.

Yes, and I think he tried to understand what he was photographing. When I interviewed him, I took some of the images along and said “please could you talk me through what we are seeing?” he had such good recall of what this machine was doing and what it was for and how much it produced in terms of how much paper was rolling off a new paper print line or how much steel was being produced in a factory per day for a car manufacturer or something. He always learnt about what he was photographing. The workers who were there appreciated the fact that he knew what they were producing on the assembly lines or in the factory. He really understood what to photograph and where and how. He knew that the audience might not understand the things that we see in the pictures. You get the impression that the photographer knows what they are photographing and are able to convey it to you in its most graphic form. If you and I haven’t seen those factories, we wouldn’t know what the hell they are until it is explained to us.

![]()

One photograph that was particularly striking to me was looking down through an enormous cylinder structure. There are two people further down, and then a few more people even further down who were super tiny.

I think the one you are thinking of is looking down the inside of a cooling tower of the Calder Hall Power Station which was one of the first nuclear power stations to feed the National Grid. Those cooling towers had just finished construction.

Maurice was invited to photograph the power station and was one of the first to photograph inside it. He wrote about it in the trade journal, saying it looked like a science fiction out of H.G. Wells. He was awed by the lack of dirt – no visible coal or soot or anything, only this tremendous depth of energy and power without grime. He said it was ominous and eerie.

The photo has two levels of figures sticking out on planks looking down this big circular void. Maurice was at the top, straddling two planks over the 300-foot void of the cooling tower chimney. It was a very dangerous picture to have made, balancing, looking down.

His pictures were used in Geneva to show the usefulness of atomic energy which was quite disingenuous because that power station was producing weapons-grade plutonium for the defence ministry as well as supplying the National Grid. Maurice didn’t know that, otherwise, I don’t think he would have agreed to do it. They confiscated his film and checked it before they sent it back and he could process it. It was heavily security-controlled. I believe those cooling towers were demolished in the 90s. Then there was a big clean-up operation as a result of the waste on the site. That picture is full of a difficult history about awe-inspiring energy and the enormous scale of cutting-edge architectural engineering for nuclear energy in that day.

![]()

It is amazing how he captures the scale of that structure, something he seemed very good at on both the architectural scale and also a more intimate scale of people at work.

Yes, he was very good at conveying a sense of scale. He often used a figure in the foreground or a person in dialogue with machinery to give a sense of scale to a machine or to show how a human being was in control of what seemed to be a vast, unknowable machine and they are often on the threshold of something that they look they are just able to control some massive papermill or river of molten metal or something.

Again, that connects back to Romantic paintings, if you think about Joseph Wright or Caspar David Friedrich, where you have this sublime spectacle and what gives it scale is this little figure on a precipice, that is exactly the way Maurice would convey drama – by showing the figure in a dialogue with the machine. That is why we called this show Industrial Sublime because it is that idea of something on the edge of your understanding, the edge of human control.

![]()

![]()

fig.i

Lara Chapman: How did you begin to research and understand Maurice Broomfield’s work?

Martin Barnes: It has been a long journey. I met Maurice nearly 15 years ago when I was introduced to him by a documentary filmmaker. I then interviewed him for the British Library’s National Sound Archive which has a collection of audio life story interviews. I thought he’d be an interesting person to interview, not least because he had been alive for most of the 20th century and had a fascinating life story.

I gradually began to understand that he still had the archive of his photography business in his house. When he worked for companies throughout Britain, across Europe and in other places he kept the copyrights, the negatives, and the contact prints. It was quite remarkable that there was this large survival of a working photographer’s commercial practice and an archive that hadn’t been dispersed to different companies.

fig.ii

What value did you see in the archive and why did you want to acquire it for the V&A’s collection?

It seemed like such an important slice of history on many levels – social history, British history, industrial history, and the history of Maurice’s work as a spectacular image maker. It also corresponded to other areas of the V&A’s interests like architecture, the production of glass, steel, ceramics and other things that we collect which were often produced in those same factories that he photographed. It seemed obvious to bring that archive into the museum and to preserve it.

What is in the archive?

The bulk of the archive is negatives and contact prints. There are about 30,000 negatives. Most of which were made over a period of about 25 years. Then, there are all his business ledgers, press clippings, an archive of trade journals and magazines that he’d illustrated and, finally, some beautiful exhibition prints. It was really fascinating to dig into the survival of this archive and to see how he had repurposed different images and how they had been used.

The exhibition and the book are a first pass at going through the huge archive to draw out some of the more spectacular images of the factories and particularly around British industry.

fig.iii

It’s amazing that the archive is so massive! In the exhibition I was intrigued that his working shots and artistic shots were often the same image. When a photograph is in a brochure or pamphlet, it is still amazing, but because of the context also somewhat unremarkable. If I hadn’t been looking at them in an exhibition context, I probably wouldn’t have given them a second thought, but when the same image is blown up, it is incredible how much it transforms. How do you think that showing photographs as artworks rather than documentary changes them? Does this create tension in his work?

That is precisely what I wanted to highlight in the exhibition. There is a backbone down the middle of the exhibition made up of display cases. In them, you have the original trade publications, company reports, statistical reports, brochures, and company manifestos. Most of those images were produced based on a commission.

I wanted to trace where the same image had appeared, say in a commissioned piece by an industrial company which would have been the original context and then in a photography magazine which is demonstrating technical abilities with colour film or black and white printing. And then the same image might have been reproduced in the Financial Times as documentation of Britain’s productivity and used as a kind of propaganda about British industry, and then he would print the exhibition large-scale for the Royal Photographic Society or to tour in an exhibition for example.

After he’d retired and almost given up on a career as a photographer in the 90s, he revisited his own archive and selected images that he felt were the most artistic to reprint. There is a set of images that Maurice himself revisited and understood still in a slightly different way, no longer needing to satisfy a brief or a client.

fig.iv

How did he manage to make images that worked across so many different types of publications and impart so many different meanings and messages?

I think he felt like the factory was like a stage set. He could produce his vision and enjoy the visual spectacle of the industry whilst knowing that he could also satisfy a brief for a client. It is all about context really – there was a clever repurposing of the image at different scales, sometimes in colour, sometimes black and white, sometimes in newsprint, and sometimes as a beautifully printed image. I think he was good at picking very graphic contrasting images which would reproduce at a small scale and a very large scale and still hold up.

Often, within two or three years of making a series of images, Maurice might select one photograph from an entire shoot – say Ford or the British Nylon Spinners or English Electric – and then make it into very large print, nearly a metre or metre-an-a-half in scale for an exhibition and take it out of context of the trade reports. Then, you don’t see any sequence of production, surrounding architecture or anything that explains what this single spectacular image is. If you have no context for the industry, you are often left wondering what is being depicted.

fig.v

What do you think the effect of removing the context was?

He was very aware that he was making quite surreal images and that by taking them out of context he understood that they could be read in a way that, divorced from their context, they are just a spectacular image. A lot of his reference points were things like Joseph Wright of Darby’s paintings where, without the title, you don’t know what the experiment being shown in the painting is. They both rely on that visual spectacle to start with.

It is a unique way of looking at a factory setting which, I imagine, was quite a hostile space. Going back to this idea of the factory as a stage set, it is interesting in the sense that the images look very natural but are actually manufactured.

A lot of the photographs were based on his initial visits to the factories. Sometimes he’d turn up the day before without any camera and just walk around the factory, getting to know the people, chatting, making pencil sketches, and noticing the way someone was standing or the quality of light with a particular machine or coming through a window or something.

He would then return with that knowledge of what it was like but then he’d amplify the scene with powerful lighting or by getting somebody to pose in a position he’d seen them the day before at work. So they are kind of performing their own job. It is a bit like reality TV which isn’t really real, but set up based on a trope of what you might see. He described it as unashamedly using the factory like a stage set and that he was the director of this play with actors who were like a cast of real characters. But he might move them around the factory or ask somebody else to stand in for somebody who was doing the job but who he thought was more photogenic. There is quite a lot of manipulation behind what appears to be an authentic, documentary image.

fig.vi

And yet, they do document a unique time in British manufacturing history. Looking back on these photos, with the perspective of a few decades, what do you think Broomfield’s photographs can teach us about the world today?

I think over the last ten years the photographs have been repurposed and we can understand them differently – in ways that Maurice might not have originally intended. The images gain new meanings over time. His pictures were originally about celebrating industry and progress and technology, intended as a public exercise in post-war productivity. Maurice was unashamed about being part of that reconstructive effort to show Britain, and particularly British factories, as capable and technologically advanced. Then, at one stage, they became about the decline of industry and the nostalgia for a loss of the technical skill, ingenuity, and high productivity of the post-war period.

In the last five to ten years, those pictures have been read around climate anxiety and crisis, and alternative form of energy and pollution. They occupy this really interesting territory where you look at them and you feel maybe simultaneously nostalgic or impressed and then you question the toxic legacy of the industry that you are seeing depicted. You’re left wondering what position the photographer occupied historically. Is it critical? Is it celebratory?

Photographs of oil rigs in the North Sea, for example, make you now think about the toxic legacy of the oil industry. The images become topical again in different ways, in different decades but because they are initially very gripping and spectacular, you are drawn into them. They have beauty and fear in them which is, again, like an eighteenth-century idea of sublime and terror and beauty mixed. That is very potent.

fig.vii

Yes, I think it comes back to this idea of context again which, I supposed runs through a lot of photography. This is more about the context of where you look at an image from and what position you have…

Yes, I think with any photography, the further away that you get from the moment the picture was produced, the more meaning it can hold. Certain images or certain photographers' works seem to get reinterpreted for the current generation and hold different meanings. Their critical fortunes can go up and down depending on how relevant they are for the particular generation. Maurice’s pictures seem to have survived in different contexts in very powerful ways. That’s partly because they are so artfully made. The craft of the images in the first place is so good that it just has an instant visual route into them.

fig.viii

Do you think photographers are working in a similar way to Broomfield today, in that they are capturing industrial landscapes with these ideas of awe and the sublime, but maybe from a more critical perspective?

Yes, I think the idea of the beauty of industrial devastation as a way of drawing you in is well-worn by now. I think the key figure is Edward Burtynsky. It’s using that initial beauty and then you realise the photo is of a toxic slick or a polluted lake, but the colours are so amazing. That tradition now is quite strong in photography.

I guess that Maurice is coming at it from a different angle. He wasn’t consciously making beautiful images which are visually seductive of things that he knew were devastating and needed to be highlighted. That is not where he is coming from in making those images. That is how we read them today.

The complexity of them is that he admired the workers. He came from a background in factories, working for Rolls Royce as a young man. They hold this ambiguity in his admiration for skill and craft and ingenuity and it puts you, as a viewer, in quite a complex position, I think.

fig.ix

Using this tradition of sublime industrial devastation comes with a tricky conflict – there is a question of whether we should be making such awful things look so beautiful. On one hand, there is a need to draw people in and to make them pay attention to environmentally damaging spaces, but there is a risk that viewers may feel pacified to the dangers through images so beautiful and amazing. Broomfield’s intention was different, he was trying to celebrate the beauty of the industrial – it feels as if the viewers’ feelings and photographer’s intentions are more aligned.

In his work, there was very little critical perspective on industry. Speaking to him, he came from a very squarely humanist, pacifist position. He was a tremendous optimist. He wanted to be helpful. He had witnessed the devastation of the Second World War and drove an ambulance during the Blitz, he was a very conscientious objector and was involved in repatriation in the war effort. For somebody of that generation, all his ambition was to rebuild the country.

He put his eggs in the basket of technology by building positive imagery of expert technological advancement and celebrating that work. That was the side he was on. He wasn’t investigative, he was working for a client and wanted to make a positive vision of industrial manufacturing. He liked the ingenuity of it, he thought it was beautiful. It is only retrospectively that we see what difficult legacies some of those things have.

fig.x

It strikes me that all the renewable and green energy innovations that are trying to gain traction today need a photographer like Broomfield to show them as amazing spaces of knowledge and industry and scale and skill. To celebrate what is happening and to show what is possible – it might help them gain more support perhaps.

Yes, and I think he tried to understand what he was photographing. When I interviewed him, I took some of the images along and said “please could you talk me through what we are seeing?” he had such good recall of what this machine was doing and what it was for and how much it produced in terms of how much paper was rolling off a new paper print line or how much steel was being produced in a factory per day for a car manufacturer or something. He always learnt about what he was photographing. The workers who were there appreciated the fact that he knew what they were producing on the assembly lines or in the factory. He really understood what to photograph and where and how. He knew that the audience might not understand the things that we see in the pictures. You get the impression that the photographer knows what they are photographing and are able to convey it to you in its most graphic form. If you and I haven’t seen those factories, we wouldn’t know what the hell they are until it is explained to us.

fig.xi

One photograph that was particularly striking to me was looking down through an enormous cylinder structure. There are two people further down, and then a few more people even further down who were super tiny.

I think the one you are thinking of is looking down the inside of a cooling tower of the Calder Hall Power Station which was one of the first nuclear power stations to feed the National Grid. Those cooling towers had just finished construction.

Maurice was invited to photograph the power station and was one of the first to photograph inside it. He wrote about it in the trade journal, saying it looked like a science fiction out of H.G. Wells. He was awed by the lack of dirt – no visible coal or soot or anything, only this tremendous depth of energy and power without grime. He said it was ominous and eerie.

The photo has two levels of figures sticking out on planks looking down this big circular void. Maurice was at the top, straddling two planks over the 300-foot void of the cooling tower chimney. It was a very dangerous picture to have made, balancing, looking down.

His pictures were used in Geneva to show the usefulness of atomic energy which was quite disingenuous because that power station was producing weapons-grade plutonium for the defence ministry as well as supplying the National Grid. Maurice didn’t know that, otherwise, I don’t think he would have agreed to do it. They confiscated his film and checked it before they sent it back and he could process it. It was heavily security-controlled. I believe those cooling towers were demolished in the 90s. Then there was a big clean-up operation as a result of the waste on the site. That picture is full of a difficult history about awe-inspiring energy and the enormous scale of cutting-edge architectural engineering for nuclear energy in that day.

fig.xii

It is amazing how he captures the scale of that structure, something he seemed very good at on both the architectural scale and also a more intimate scale of people at work.

Yes, he was very good at conveying a sense of scale. He often used a figure in the foreground or a person in dialogue with machinery to give a sense of scale to a machine or to show how a human being was in control of what seemed to be a vast, unknowable machine and they are often on the threshold of something that they look they are just able to control some massive papermill or river of molten metal or something.

Again, that connects back to Romantic paintings, if you think about Joseph Wright or Caspar David Friedrich, where you have this sublime spectacle and what gives it scale is this little figure on a precipice, that is exactly the way Maurice would convey drama – by showing the figure in a dialogue with the machine. That is why we called this show Industrial Sublime because it is that idea of something on the edge of your understanding, the edge of human control.

figs.xiii,xiv

Maurice Broomfield

was born to a working-class family near Derby in 1916, later working at the

city’s Rolls Royce factory after leaving school at the age of fifteen. He

attended Derby Art College in the evenings, then worked in advertising before

earning a position as Britain’s premier industrial photographer throughout the

1950s and 60s. He died in 2010.

Martin Barnes is

Senior Curator of Photographs at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A)

London, which he joined in 1995 from his previous position at the Walker Art

Gallery, Liverpool. Since 1997 he has worked with the V&A’s National

Collection of the Art of Photography, building and researching the collection

and devising exhibitions. He was the Lead Curator for the V&A’s new

Photography Centre which opened in autumn 2018. Martin has curated numerous UK

and international touring exhibitions for the V&A and other organisations, and

has published widely.

Lara Chapman is a

London-based writer, design researcher & curator. Her work explores the

intersection of the climate crisis & design & the stories we can tell

through everyday objects. Lara has written for publications such as Disegno,Architectural Review & DAMN. She has exhibited projects at

the V&A & Dutch Design Week. She holds an MA in Design Curating and

Writing from Design Academy Eindhoven & a BA in Product and Furniture

Design. She is currently an assistant curator at the Design Museum in London.

www.lara-chapman.com

Lara Chapman is a

London-based writer, design researcher & curator. Her work explores the

intersection of the climate crisis & design & the stories we can tell

through everyday objects. Lara has written for publications such as Disegno,Architectural Review & DAMN. She has exhibited projects at

the V&A & Dutch Design Week. She holds an MA in Design Curating and

Writing from Design Academy Eindhoven & a BA in Product and Furniture

Design. She is currently an assistant curator at the Design Museum in London.

www.lara-chapman.com

visit

Maurice Broomfield Industrial

Sublime is a free exhibition at the V&A South Kensington, London, until 27

November 2022, more information at:

www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/maurice-broomfield-industrial-sublime

The V&A have

also published a book to coincide with the exhibition, available from bookshops

widely and from the museum shop here:

www.vam.ac.uk/shop/books/drawings-paintings-photos-prints/industrial-sublime%3A-photographs-by-maurice-broomfield-162455.html

images

fig.i Installation view of Maurice Broomfield Industrial Sublime display at V&A (c) Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

fig.ii Maurice Broomfield. Preparing a Warp from Nylon Yarn, British Nylon Spinners, Pontypool, Wales. 1964.

Digital C-type print, printed 2006. Given by the artist. © Estate of Maurice Broomfield.

fig.iii Maurice Broomfield. Die Casting, Qualcast Lawnmower Works, Derbyshire.

1954. Gelatin silver print, printed 1995.

Given by the artist. © Estate of Maurice Broomfield.

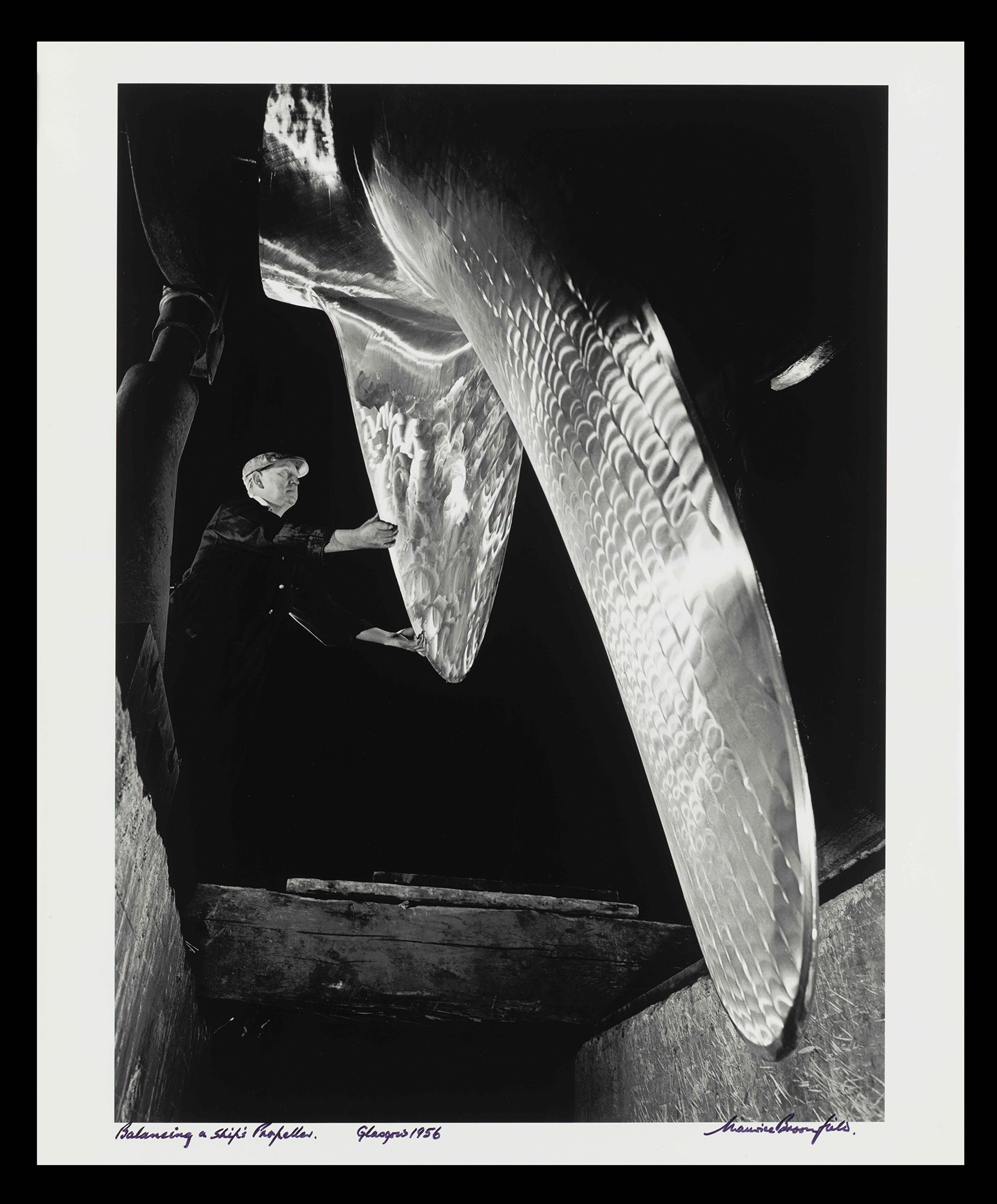

fig.iv Maurice Broomfield. Balancing a Ship Propeller, Bull’s Metal and Marine Shipyard, Glasgow, Scotland. 1956.

Gelatin silver print, printed 1995

Given by the artist. © Estate of Maurice Broomfield.

fig.v Maurice Broomfield. Two Men and Four Tanks, Joseph Crosfield, Warrington. 1962.

Gelatin-silver print. Given by Nick Broomfield. © Estate of Maurice Broomfield.

fig.vi Maurice Broomfield. Wire Manufacture, Somerset Wire Company, Cardiff Factory. 1964. Gelatin silver print.

Given by the artist.

© Estate of Maurice Broomfield.

fig.vii Maurice Broomfield. North Sea Rig, Gas Council 1967.

Gelatin-silver print. Given by Nick Broomfield. © Estate of Maurice Broomfield.

fig.viii Maurice Broomfield. Assembling a Former for a Stator, English Electric, Stafford.

1960.

Digital C-type print, printed 2007. Given by the artist. © Estate of Maurice Broomfield.

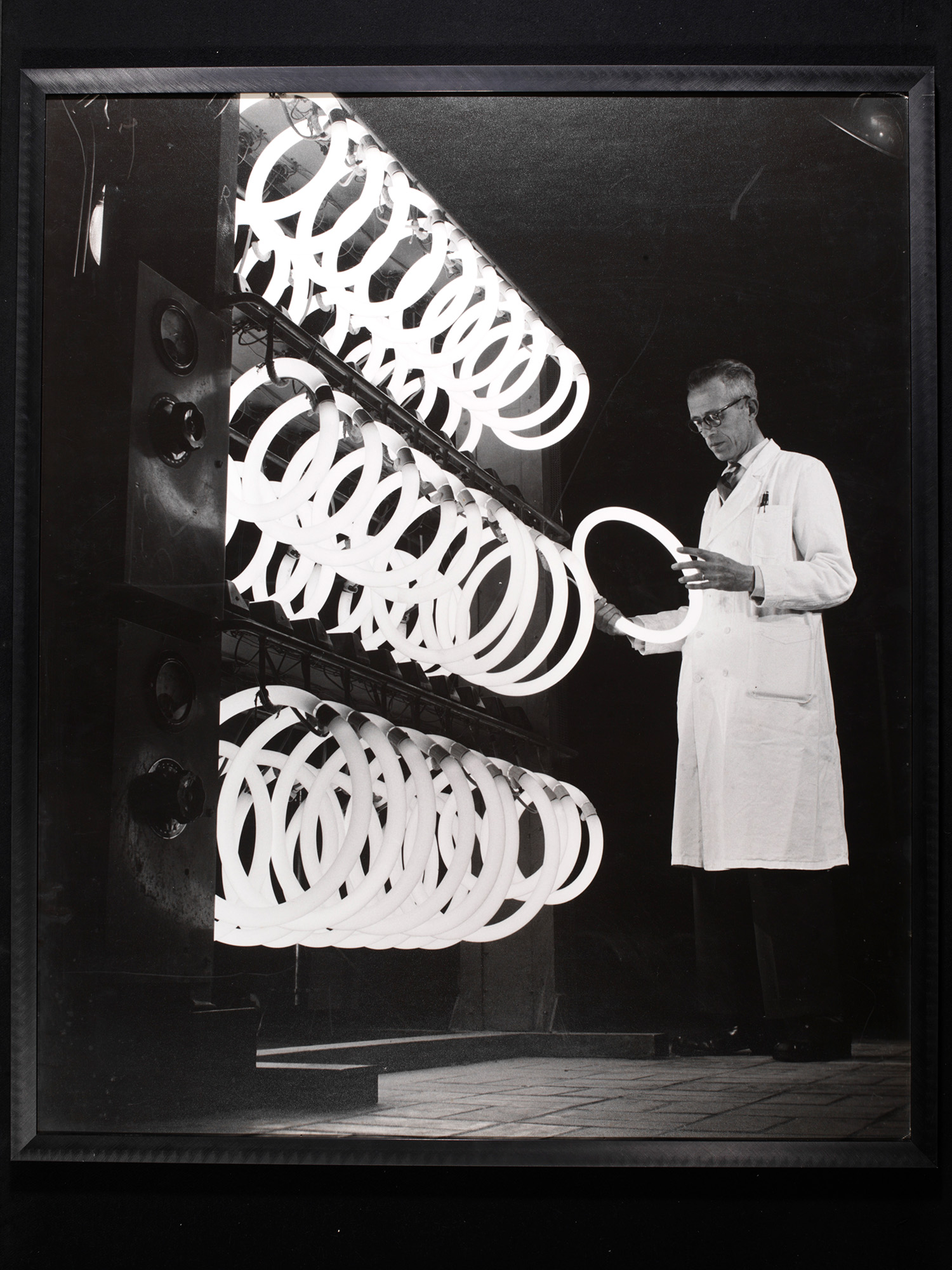

fig.ix Maurice Broomfield. Testing Fluorescent Tubes, Philips, Eindhoven, 1958.

Gelatin-silver print. Given by Nick Broomfield. © Estate of Maurice Broomfield.

fig.x Maurice Broomfield. Tapping a Furnace, Ford, Dagenham, Essex, 1954.

Digital C-type print, printed 2006. © Estate of Maurice Broomfield.

fig.xi Maurice Broomfield. Woman Examining a Sample, Shell International, Holland Laboratories, 1968.

Gelatin-silver print. Given by Nick Broomfield. © Estate of Maurice Broomfield.

fig.xii Maurice Broomfield. Testing Ceramic Insulator Pots, Royal Doulton, 1955.

Gelatin-silver print. Given by Nick Broomfield. © Estate of Maurice Broomfield.

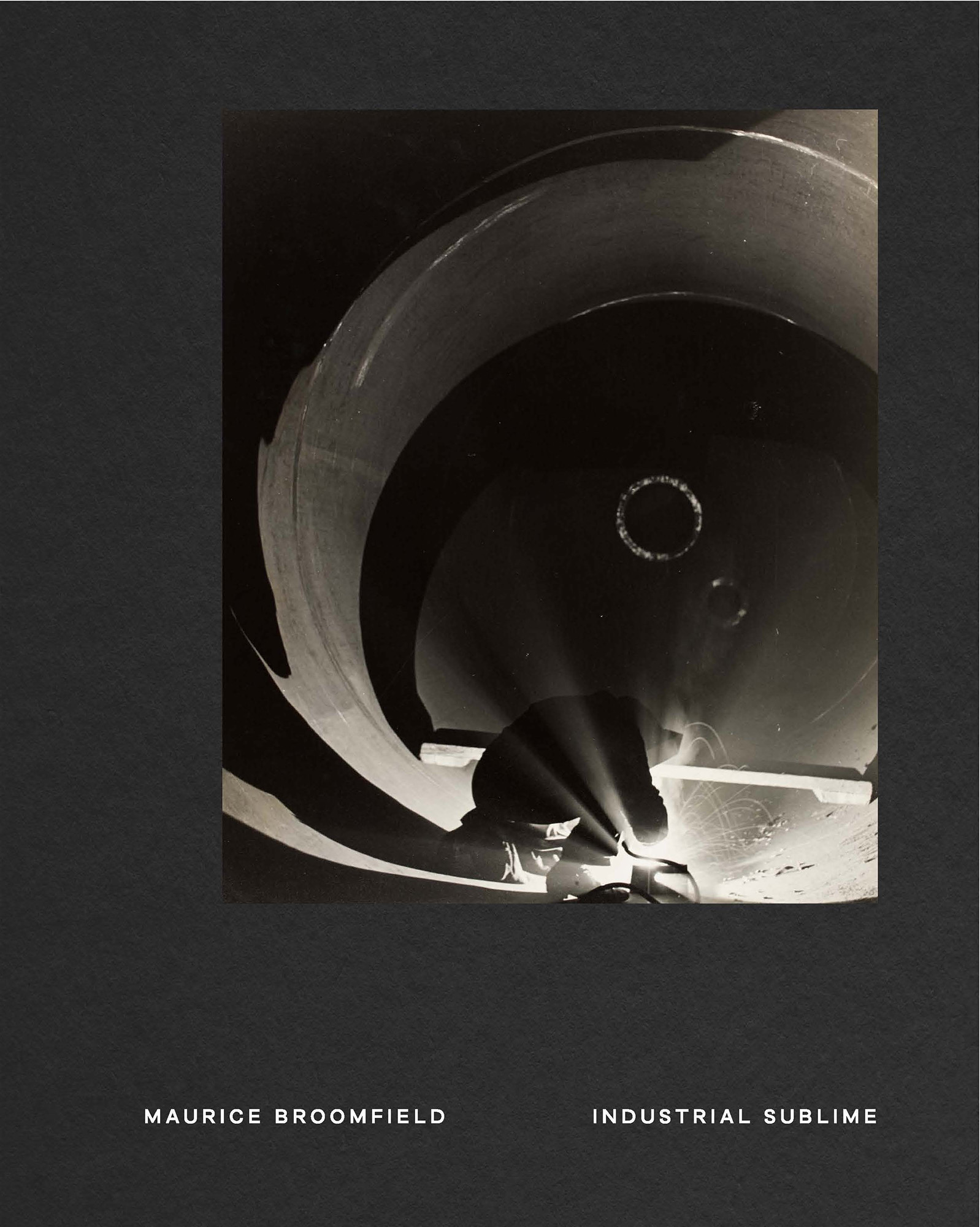

fig.xiii Installation view of Maurice Broomfield Industrial Sublime display at V&A (c) Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

fig.xiv Cover of Industrial Sublime: Photographs by Maurice Broomfield, ed. Martin Barnes, published by the V&A, 2021.

publication date

14 November 2022

tags

Archive, Martin Barnes, Maurice Broomfield, Labour, Lara Chapman, Collection, Industry, Oil rig, Photography, Post industrial, Power station, Sublime, V&A, Victoria and Albert Museum, Workers

www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/maurice-broomfield-industrial-sublime

The V&A have also published a book to coincide with the exhibition, available from bookshops widely and from the museum shop here:

www.vam.ac.uk/shop/books/drawings-paintings-photos-prints/industrial-sublime%3A-photographs-by-maurice-broomfield-162455.html