Julian Opie & a virtual extension of place

A new project by Julian Opie sees the artist digitally &

radically expand the walls of Lisson Gallery, using virtual reality to imagine

an uncanny & playful extension of the exhibition space. Rooted in the

pandemic & screen-mediated lives, Will Jennings explores physical &

digital worlds created by the artist.

We are used to the cliché of modern art’s white-cube

galleries being minimally dressed. When Martin Creed created Work No. 227:

The lights going on and off (2000) in which – as the title suggests – the gallery

was nothing other than a light bulb intermittently turning on then off,

illuminating only barren walls, floor, and ceiling, it was perhaps a high point

of the minimalistic (though perhaps celebrated the gallery architecture more

than any other installation).

Julian Opie’s new show for Lisson Gallery comes close, and in the process with ingenuity and wit shows a way that exhibiting and art can use emerging technologies in creative and creatively beneficial ways after the years of NFT monkeys and Covid-era online art galleries that amounted to a website with a password.

![]()

![]()

This show is a gear-shift away from the often-awkwardly technologised art of that Covid-era, though the pandemic is present throughout the exhibition, OP.VR@LISSON/London. That title, which doesn’t flow from the tongue, is a clue to the central component of the installation. A virtual reality [VR] experience is the main work in show, though there are poetic resonances in context and form between what is experienced once inside the headset and the other – more traditionally mounted – works in the gallery spaces beyond.

VR is often underwhelming in contemporary art. Many a time has a visitor queued up to take their turn to wear a headset to then be confronted with a glitchy, disappointing immersive experience which is less exciting, engaging, or creative than a typical VR video game. Art hasn’t yet found its niche in relation to such technology, and won’t so long as it apes other media which do it better with larger audiences and greater funding. Opie’s first VR work, OP.VR/01, does engage in new ways, as well as importantly playing with his own art practice, the gallery context, and the potentials of virtuality.

![]()

![]()

Once wearing the VR headset, the visitor finds themselves in a room remarkably similar to the one they had just been standing it, but whereas before the space had been open, light-filled, with no objects in the space other than some wall-mounted vinyl cut-outs, the visitor now sees Natalie (2016), a recognisably Opie work of a single portrait within an otherwise familiar empty and immaculate white wall gallery space – except, it was entirely digital.

The digital room itself is an uncanny simulacra of a classic art space: wooden floor, crisp white walls, and when looking up 16 gallery track lights can be seen lighting up the virtual space. This is a familiar environment, made slightly more uncanny by it’s similarity in tone to the real gallery just outside of VR vision, which the visitor knows is there as a physical bounding but not part of the world currently experiences.

In front is a closed door to the right side and an inviting opening to the left. When entering the open one, a short corridor space is revealed, it seems to lead here the closed door was. But when getting there, and returning into the space just exited, the works on display are different. Now, two moving image works address one another across the digital gallery, both a view from a car moving through a landscape, one within a looping dark tunnel recognisable by geometric colour forms whizzing past from which we read headlights and architecture, while an external landscape faces it, devoid of car as we are taken on a picturesque rollercoaster.

![]()

![]()

This departure from the room and return into it to find not only new works but often an entirely new architectural environment repeats and repeats, to the point that one forgets not only how many times this room has been reinterpreted but that we forget we are bounded by an actual physical gallery space to begin with. On one entry a visitor’s eyes are flung upwards to see the space three times taller and topped out with 16 glazed panels opening onto a seamless blue sky. Then on a later exit/entry we find the walls have collapsed and now we are within a grand neoclassical cultural palace, now full of outline versions of French church towers and domestic façades. In Bastide(2021), Opie has distilled medieval architecture from the French countryside in which he lived over Covid lockdowns, and in the VR version as a visitor walks around the space to approach church towers bells start to play, increasing in velocity and magnitude, bellying the minimal calm of the stick-scene beyond the digital boundary.

![]()

![]()

![]()

This reimagination of Opie’s personal pandemic landscape isn’t the only way in which the Covid period has entered the show which extends well beyond the VR element and into the various analogue rooms of Lisson Gallery. Works often occur in both virtual and digital, a repeating and overlapping of the two realms, including a series of dancing figures. On a short repeating loop, figures dancing to electronic music by are Opie’s homage to TikTok dance trends, and through that an observation of how the expanding digital of social media offers at once a closed, personal, narrowed experience, but also one which opens out to a whole world of new connections, geographies, geometries, and meaning. Elsewhere in the gallery wall-based colour geometric shapes form a simplified landscape as seen through a car driving through the French countryside – speaking to the VR films and also the last few years mediating life through screens.

![]()

![]()

fig.viii,ix

A climbing-frame like sculpture fills the gallery’s courtyard, and it’s another uncanny return. A three-dimensional black frame condensed version of Bastide. Now, however, the church towers and architectural surfaces are within reach and not beyond the mirage of virtual space. It’s a call-back, but also a reminder of physicality in a world which see-saws between realms, accelerated over the pandemic. Within the play and technological experiment, there are fascinating spatial experiences which might here be used for art experience – and I can see how Opie’s multi-room approach can offer smaller galleries ideas to expand their offer – but perhaps also point towards experimental modes of using emergent virtual technologies in our reading of space.

Ultimately, the works on show in all mediums concern the body, its containment, and its release. That they were born or re-imagined over Covid, and then either commenting upon the technologies propelled over Covid and which have reshaped our spatial experiences makes this show only the richer.

Julian Opie’s new show for Lisson Gallery comes close, and in the process with ingenuity and wit shows a way that exhibiting and art can use emerging technologies in creative and creatively beneficial ways after the years of NFT monkeys and Covid-era online art galleries that amounted to a website with a password.

figs.i,ii

This show is a gear-shift away from the often-awkwardly technologised art of that Covid-era, though the pandemic is present throughout the exhibition, OP.VR@LISSON/London. That title, which doesn’t flow from the tongue, is a clue to the central component of the installation. A virtual reality [VR] experience is the main work in show, though there are poetic resonances in context and form between what is experienced once inside the headset and the other – more traditionally mounted – works in the gallery spaces beyond.

VR is often underwhelming in contemporary art. Many a time has a visitor queued up to take their turn to wear a headset to then be confronted with a glitchy, disappointing immersive experience which is less exciting, engaging, or creative than a typical VR video game. Art hasn’t yet found its niche in relation to such technology, and won’t so long as it apes other media which do it better with larger audiences and greater funding. Opie’s first VR work, OP.VR/01, does engage in new ways, as well as importantly playing with his own art practice, the gallery context, and the potentials of virtuality.

figs.iii,iv

Once wearing the VR headset, the visitor finds themselves in a room remarkably similar to the one they had just been standing it, but whereas before the space had been open, light-filled, with no objects in the space other than some wall-mounted vinyl cut-outs, the visitor now sees Natalie (2016), a recognisably Opie work of a single portrait within an otherwise familiar empty and immaculate white wall gallery space – except, it was entirely digital.

The digital room itself is an uncanny simulacra of a classic art space: wooden floor, crisp white walls, and when looking up 16 gallery track lights can be seen lighting up the virtual space. This is a familiar environment, made slightly more uncanny by it’s similarity in tone to the real gallery just outside of VR vision, which the visitor knows is there as a physical bounding but not part of the world currently experiences.

In front is a closed door to the right side and an inviting opening to the left. When entering the open one, a short corridor space is revealed, it seems to lead here the closed door was. But when getting there, and returning into the space just exited, the works on display are different. Now, two moving image works address one another across the digital gallery, both a view from a car moving through a landscape, one within a looping dark tunnel recognisable by geometric colour forms whizzing past from which we read headlights and architecture, while an external landscape faces it, devoid of car as we are taken on a picturesque rollercoaster.

figs.v,vi

This departure from the room and return into it to find not only new works but often an entirely new architectural environment repeats and repeats, to the point that one forgets not only how many times this room has been reinterpreted but that we forget we are bounded by an actual physical gallery space to begin with. On one entry a visitor’s eyes are flung upwards to see the space three times taller and topped out with 16 glazed panels opening onto a seamless blue sky. Then on a later exit/entry we find the walls have collapsed and now we are within a grand neoclassical cultural palace, now full of outline versions of French church towers and domestic façades. In Bastide(2021), Opie has distilled medieval architecture from the French countryside in which he lived over Covid lockdowns, and in the VR version as a visitor walks around the space to approach church towers bells start to play, increasing in velocity and magnitude, bellying the minimal calm of the stick-scene beyond the digital boundary.

fig.vii

This reimagination of Opie’s personal pandemic landscape isn’t the only way in which the Covid period has entered the show which extends well beyond the VR element and into the various analogue rooms of Lisson Gallery. Works often occur in both virtual and digital, a repeating and overlapping of the two realms, including a series of dancing figures. On a short repeating loop, figures dancing to electronic music by are Opie’s homage to TikTok dance trends, and through that an observation of how the expanding digital of social media offers at once a closed, personal, narrowed experience, but also one which opens out to a whole world of new connections, geographies, geometries, and meaning. Elsewhere in the gallery wall-based colour geometric shapes form a simplified landscape as seen through a car driving through the French countryside – speaking to the VR films and also the last few years mediating life through screens.

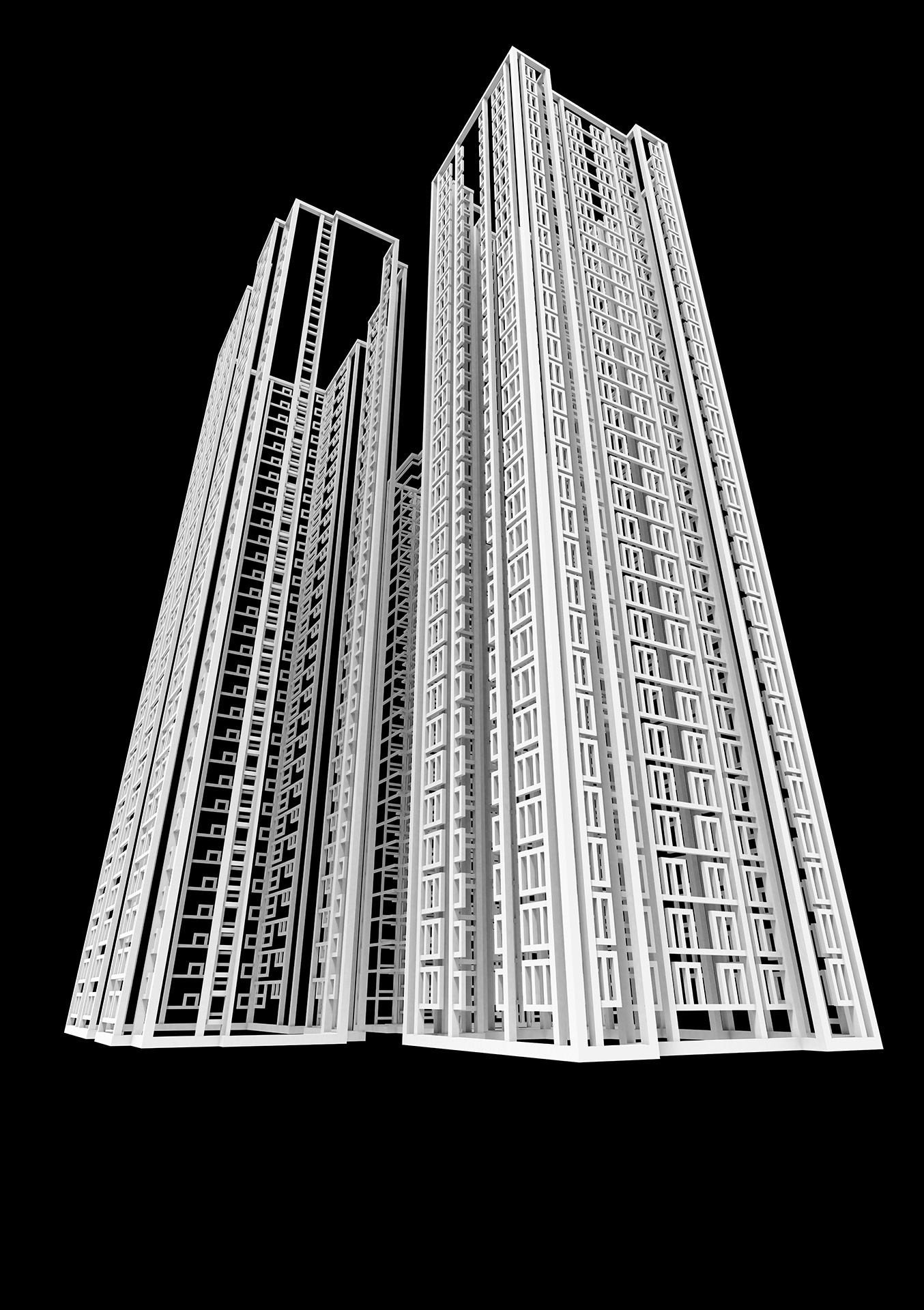

fig.viii,ix

A climbing-frame like sculpture fills the gallery’s courtyard, and it’s another uncanny return. A three-dimensional black frame condensed version of Bastide. Now, however, the church towers and architectural surfaces are within reach and not beyond the mirage of virtual space. It’s a call-back, but also a reminder of physicality in a world which see-saws between realms, accelerated over the pandemic. Within the play and technological experiment, there are fascinating spatial experiences which might here be used for art experience – and I can see how Opie’s multi-room approach can offer smaller galleries ideas to expand their offer – but perhaps also point towards experimental modes of using emergent virtual technologies in our reading of space.

Ultimately, the works on show in all mediums concern the body, its containment, and its release. That they were born or re-imagined over Covid, and then either commenting upon the technologies propelled over Covid and which have reshaped our spatial experiences makes this show only the richer.

Julian Opie was born in London in 1958 and lives & works in London. He graduated from Goldsmith’s School of Art, London in 1982. Exhibitions have been staged at Berardo Museum, Lisbon, Portugal (2020); Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, Japan (2019); Gerhardsen Gerner, Oslo, Norway (2019); The National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia (2018); National Portrait Gallery, London, UK (2017); Suwon Ipark Museum of Art, Korea (2017); Fosun Foundation, Shanghai, China (2017); Fundacion Bancaja, Valencia, Spain (2017); Kunsthalle Helsinki, Finland (2015); Museum of Contemporary Art Krakow (MoCAK), Poland (2014); National Portrait Gallery, London, UK (2011); IVAM, Valencia, Spain (2010); MAK, Vienna, Austria (2008); CAC Malaga, Spain (2006); Neues Museum, Nuremberg, Germany (2003); Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, UK (2001); Kunstverein Hannover, Germany (1994); & Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, UK (1985). Major group exhibitions include I Want! I Want! Art & Technology at Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Birmingham, UK (2017); This Is Not The Reality. What Kind Of Reality?, 57th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy (2017); the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK (2016); Barbican Art Gallery, London, UK (2014); Tate Britain, London, UK (2013); the Shanghai Biennale (2006); 11th Biennial of Sydney (1998); documenta 8, Kassel, Germany (1987); & XIIème Biennale de Paris (1985). Public projects include 'Walking in Taipei', Taipei, Taiwan & Walking in Hong Kong, Tower 535, Hong Kong (2016); Arendt & Medernach, Luxembourg (2016); Heathrow Terminal 1 (1998); & the prison Wormwood Scrubs, London (1994); as well as public work for hospitals, such as the Lindo Wing, St. Mary's Hospital, London (2012) & Barts & the London Hospital (2003). His design for the band Blur’s album Best of Blur (2000) was awarded the Music Week CADS for Best Illustration in 2001.

www.julianopie.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.willjennings.info

visit

OP.VR@LISSON by Julian Opie is on at Lisson Gallery, 27 Bell Street, London, until 8 April 2023. Free slots for the VR element of the exhibition should be booked in advance. Full information at:

www.lissongallery.com/exhibitions/julian-opie-op-vr-hem-london

images

figs.i-iii,v,vi Details of Julian Opie, OP.VR/01 (2022). Virtual reality installation. Edition of 3 and 1 AP.

fig.iv

Portrait of Julian Opie (2023)

© Julian Opie; Courtesy Lisson Gallery

fig.vii

Dance 1 (2022).

Animated poster © Julian Opie; Courtesy Lisson Gallery

fig.viii,ix

Installation

views: Julian Opie, OP.VR@LISSON/London © Julian Opie; Courtesy Lisson Gallery

publication date

25 March 2023

tags

Architecture, Church, Martin Creed, Car, Covid, Dance, Dancing, Digital,

France, Gallery, Landscape, Lisson Gallery, Will Jennings, Pandemic, Technology, TikTok, Julian

Opie, Virtual Reality, Screen, Sculpture

www.lissongallery.com/exhibitions/julian-opie-op-vr-hem-london