Pilvi Takala’s cosplay critique of the neoliberal workplace

The working environments & structures of shopping centre security & office workers are carefully studied by artist Pilvi Takala in her solo exhibition at Goldsmiths CCA. Adopting the behaviours & costume of neoliberal workplaces, she critiques conditions & architectures of the modern world, as Will Wiles discovers.

Pilvi

Takala’s art exhibits in video, but the medium it works on is directly under

the viewer’s skin. On Discomfort, the Finnish artist’s ideally named

show at the Goldsmiths Centre of Contemporary art, is a disturbing experience –

all the more so because its methods are minimal. Takala doesn’t shock or

outrage. Her works slide a very slender blade into social conventions we hardly

even register, and prises them open with gentle leverage. It works somewhere in

a hinterland between the constructive voyeurism of Sophie Calle and the

exquisite distress of Curb Your Enthusiasm.

There is a major new work to discuss, but it should be put in proper context by looking at her record. Wallflower (2006), the earliest work on display, is small in comparison to later ambitious interventions but shows the methodology fully formed. Takala attends a tea dance mostly populated by senior citizens and families. In a sea of leisurewear, she is drastically overdressed in a flamboyant peach ballgown; she is also alone, and sits watching couples dancing. That’s it – not intensely disruptive behaviour, but an anomalous and unnerving presence in the room. Has she been stood up? Is she waiting to be asked to dance? Pleasant but entirely passive, she gives no clues, and sits emitting Miss Havisham radioactivity.

![]()

This tactic of destabilising passivity takes another step forward in The Trainee (2008), which ushers in Takala’s interest in the workplace. This film depicts a month the artist spent posing as a trainee at the Helsinki office of the accountant Deloitte. To begin with her activities are quite typical, but they steadily devolve into almost total inactivity: sitting at a hot desk with no computer, staring steadily into space; quietly occupying a seat by the law library and doing nothing; riding the elevator up and down, without pressing any buttons. If challenged, she chats nicely, saying that she is doing “brain work” and mentally composing her dissertation.

The workers around her are amused and curious, and any confrontation takes the form of gentle interrogation. But the film is paired with another, which shows extracts from email exchanges that gesture towards psychological turmoil taking place beyond the frame. “Obviously she has some kind of mental problem,” one communication states. Another says that people in the tax department find Takala’s presence scary. “People spend useless amounts of time speculating on this issue,” another complains.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Takala’s Bartleby performance is enough to destabilise what is, behind the hot desk flexibility, obviously a fairly strait-laced environment. In The Stroker (2018) she turns from subversion to outright terrorism. Roaming the SelgasCano-designed halls of super-trendy east London co-working environment Second Home, Takala greets the people she passes and touches them on the arm or back. In an office environment – even in a pot-plant-infested haunt of creatives – this invasion of personal space is more or less akin to a bombing campaign, and prompts a range of reactions, the most benign of which is friendly puzzlement. (Revealingly, men are more hostile towards it than women.)

Like The Trainee, The Stroker is displayed across two screens, one showing the touching and the other showing discussions about the touching. It is quite brilliantly unsettling to watch considering how little actually takes place – throughout these works, a key element is suspense, the possibility that something dreadful might happen, that the situation might lurch into Tim Robinson’s excruciating I Think You Should Leave. But it never does.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Another feature of The Trainee and The Stroker have in common is the collusion of individuals at the host organisations – after all, neither transgression would be permitted to last long without it. This provides the lightning rod which attracts the irate emails Takala compiles into her work, and disseminates the cover story. In the case of The Stroker, this is the extraordinary claim that Takala is part of a service called Personnel Touch being provided by the workplace to overcome deficits in human contact and enhance productivity, a jargonated blandishment that deflects most criticism (but not all – some remain furious, not unreasonably.)

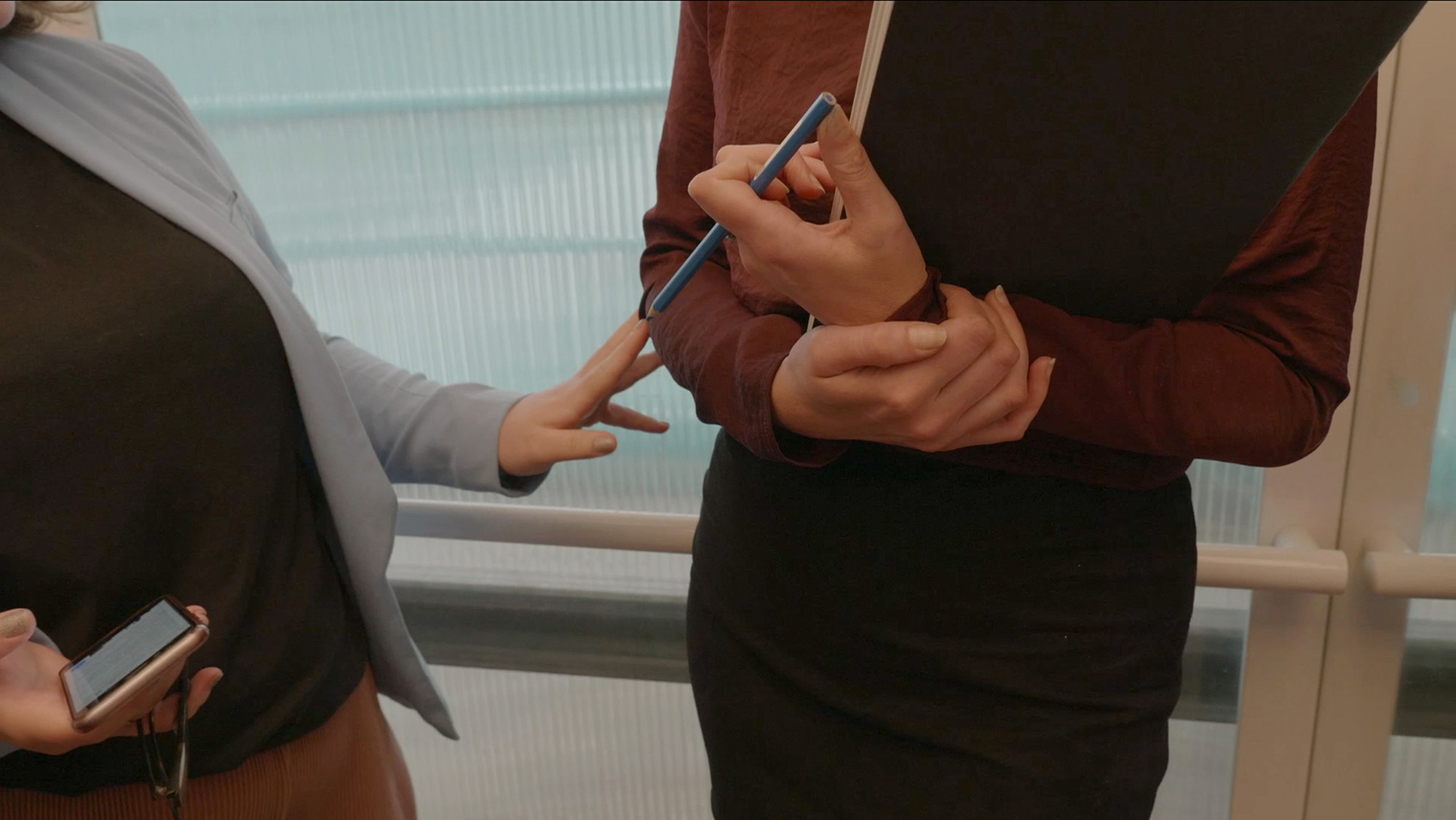

Takala also puts thought into the environments in which the films are shown – one of the screens showing The Trainee plays at the end of an office conference table, for instance. Close Watch (2022), the latest and most ambitious work on show, plays inside a large-mirrored box. Once inside, the viewer finds that the mirrors are one-way glass, and they can see out at other unsuspecting people trying to find their way in. Originally shown within the compact Finland Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2022, in Close Watch Takala trained as a security guard and then spent six months working at Finland’s largest shopping centre.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

It does not have the candid camera feel of other works – instead it takes the form of a workshop arranged by Takala after this experience, involving some of the guards with whom she worked, filmed with their knowledge. Facilitators help the group roleplay trough a couple of difficult or sensitive scenarios, probing how the guards feel about them and different ways to respond. Rather than being one of the facilitators, the artist wears a guard uniform and sits with her former colleagues. Inside dimly lit mirrored box, the viewers sit on ergonomic chairs and watch across two screens, as if sitting in a control room and observing.

It’s a fascinating exercise in occupational art – at times, it must be said, pretty boring in a mesmerising way, like sitting through human resources evaluations. One gets the sense that the occasional air of tedium is an important part of the message. The scenarios explored by the guards involve consequential human drama, such as how to handle a rough and rude customer, and how to handle a situation where that customer is being quite heavily handled by an overly forceful colleague. Other roleplays involve dynamic between guards: what to do when overhearing a racist joke, or when guards lightly discuss what is obviously excessive or even dangerous behaviour by an absent colleague. Close Watch is less directly confrontational than Takala’s prior works, even though it deals directly with the dynamics of confrontation. The discomfort takes a step back, becomes vicarious – aided by the privacy and low lighting of the “control room” setting.

![]()

The layers of concealment and separation between viewer and situation – we are sitting in our private camouflaged box watching guard relive scenarios – causes the spectator to wonder if we are truly outside the art, or another part of Takala’s apparatus of discomfort. The guards are expected to deal with volatile and difficult situations, and to carefully tread a line between their employer’s expectation that order be fully maintained and the bounds of a liberal society, and are constantly under an impassive and sometimes bored bureaucratic gaze. The “real” guards mostly come across as thoughtful and caring individual trying to do their best – but, of course, they know they are being watched.

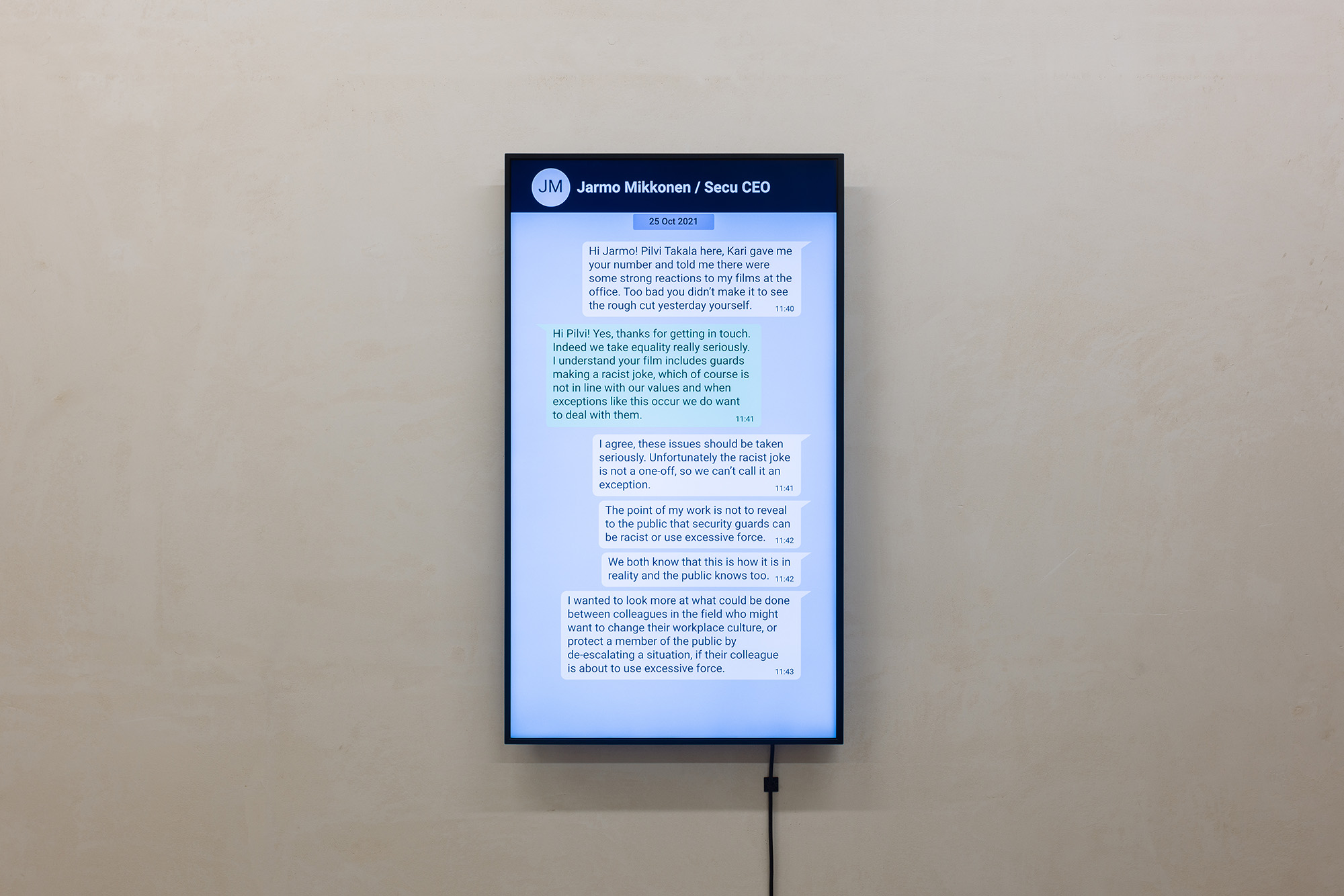

Close Watch lacks the squirming efficacy of works like The Stroker, but it’s a nicely composed microcosm of neoliberalism – in particular its lack of obvious central authority, and reliance instead on pervasive mutual surveillance. A screen that precedes it shows WhatsApps related to the project, giving an air of transparency, although growing familiarity with Takala’s work means we might mistrust such an impression. At times one wonders where the camera is.

There is a major new work to discuss, but it should be put in proper context by looking at her record. Wallflower (2006), the earliest work on display, is small in comparison to later ambitious interventions but shows the methodology fully formed. Takala attends a tea dance mostly populated by senior citizens and families. In a sea of leisurewear, she is drastically overdressed in a flamboyant peach ballgown; she is also alone, and sits watching couples dancing. That’s it – not intensely disruptive behaviour, but an anomalous and unnerving presence in the room. Has she been stood up? Is she waiting to be asked to dance? Pleasant but entirely passive, she gives no clues, and sits emitting Miss Havisham radioactivity.

This tactic of destabilising passivity takes another step forward in The Trainee (2008), which ushers in Takala’s interest in the workplace. This film depicts a month the artist spent posing as a trainee at the Helsinki office of the accountant Deloitte. To begin with her activities are quite typical, but they steadily devolve into almost total inactivity: sitting at a hot desk with no computer, staring steadily into space; quietly occupying a seat by the law library and doing nothing; riding the elevator up and down, without pressing any buttons. If challenged, she chats nicely, saying that she is doing “brain work” and mentally composing her dissertation.

The workers around her are amused and curious, and any confrontation takes the form of gentle interrogation. But the film is paired with another, which shows extracts from email exchanges that gesture towards psychological turmoil taking place beyond the frame. “Obviously she has some kind of mental problem,” one communication states. Another says that people in the tax department find Takala’s presence scary. “People spend useless amounts of time speculating on this issue,” another complains.

Takala’s Bartleby performance is enough to destabilise what is, behind the hot desk flexibility, obviously a fairly strait-laced environment. In The Stroker (2018) she turns from subversion to outright terrorism. Roaming the SelgasCano-designed halls of super-trendy east London co-working environment Second Home, Takala greets the people she passes and touches them on the arm or back. In an office environment – even in a pot-plant-infested haunt of creatives – this invasion of personal space is more or less akin to a bombing campaign, and prompts a range of reactions, the most benign of which is friendly puzzlement. (Revealingly, men are more hostile towards it than women.)

Like The Trainee, The Stroker is displayed across two screens, one showing the touching and the other showing discussions about the touching. It is quite brilliantly unsettling to watch considering how little actually takes place – throughout these works, a key element is suspense, the possibility that something dreadful might happen, that the situation might lurch into Tim Robinson’s excruciating I Think You Should Leave. But it never does.

Another feature of The Trainee and The Stroker have in common is the collusion of individuals at the host organisations – after all, neither transgression would be permitted to last long without it. This provides the lightning rod which attracts the irate emails Takala compiles into her work, and disseminates the cover story. In the case of The Stroker, this is the extraordinary claim that Takala is part of a service called Personnel Touch being provided by the workplace to overcome deficits in human contact and enhance productivity, a jargonated blandishment that deflects most criticism (but not all – some remain furious, not unreasonably.)

Takala also puts thought into the environments in which the films are shown – one of the screens showing The Trainee plays at the end of an office conference table, for instance. Close Watch (2022), the latest and most ambitious work on show, plays inside a large-mirrored box. Once inside, the viewer finds that the mirrors are one-way glass, and they can see out at other unsuspecting people trying to find their way in. Originally shown within the compact Finland Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2022, in Close Watch Takala trained as a security guard and then spent six months working at Finland’s largest shopping centre.

It does not have the candid camera feel of other works – instead it takes the form of a workshop arranged by Takala after this experience, involving some of the guards with whom she worked, filmed with their knowledge. Facilitators help the group roleplay trough a couple of difficult or sensitive scenarios, probing how the guards feel about them and different ways to respond. Rather than being one of the facilitators, the artist wears a guard uniform and sits with her former colleagues. Inside dimly lit mirrored box, the viewers sit on ergonomic chairs and watch across two screens, as if sitting in a control room and observing.

It’s a fascinating exercise in occupational art – at times, it must be said, pretty boring in a mesmerising way, like sitting through human resources evaluations. One gets the sense that the occasional air of tedium is an important part of the message. The scenarios explored by the guards involve consequential human drama, such as how to handle a rough and rude customer, and how to handle a situation where that customer is being quite heavily handled by an overly forceful colleague. Other roleplays involve dynamic between guards: what to do when overhearing a racist joke, or when guards lightly discuss what is obviously excessive or even dangerous behaviour by an absent colleague. Close Watch is less directly confrontational than Takala’s prior works, even though it deals directly with the dynamics of confrontation. The discomfort takes a step back, becomes vicarious – aided by the privacy and low lighting of the “control room” setting.

The layers of concealment and separation between viewer and situation – we are sitting in our private camouflaged box watching guard relive scenarios – causes the spectator to wonder if we are truly outside the art, or another part of Takala’s apparatus of discomfort. The guards are expected to deal with volatile and difficult situations, and to carefully tread a line between their employer’s expectation that order be fully maintained and the bounds of a liberal society, and are constantly under an impassive and sometimes bored bureaucratic gaze. The “real” guards mostly come across as thoughtful and caring individual trying to do their best – but, of course, they know they are being watched.

Close Watch lacks the squirming efficacy of works like The Stroker, but it’s a nicely composed microcosm of neoliberalism – in particular its lack of obvious central authority, and reliance instead on pervasive mutual surveillance. A screen that precedes it shows WhatsApps related to the project, giving an air of transparency, although growing familiarity with Takala’s work means we might mistrust such an impression. At times one wonders where the camera is.

Pilvi Takala

(b.1981, Finland) creates video works based on performative interventions in

which she researches specific communities in order to process social structures

and question the normative rules and truths of our behaviour in different

contexts. Her works show that it is often possible to learn about the implicit

rules of a social situation simply through its disruption. Takala represented

Finland at the 59th Venice Biennial 2022 and her work has also been shown at Mediacity

Biennale, Seoul (2021), Moscow Museum of Modern Art (2021), Künstlerhaus Bremen

(2019), Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki (2018), CCA Glasgow (2016),

Manifesta 11, Zurich (2016), Centre Pompidou, Paris (2015), MoMA PS1, New York

(2014), Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2013), New Museum, NYC (2012), Kunsthalle Basel

(2011), Witte de With, Rotterdam (2010) and the 9th Istanbul Biennial (2005). Takala

won the Dutch Prix de Rome in 2011, the Emdash Award in 2013, and the Finnish

State Prize for Visual Arts in 2013. The artist divides her time between Berlin

and Helsinki.

www.pilvitakala.com

Will Wiles is

the author of four novels, most recently The Last Blade Priest (Angry Robot,

2022).

www.angryrobotbooks.com/books/the-last-blade-priest

www.angryrobotbooks.com/books/the-last-blade-priest

visit

On Discomfort, by Pilvi Takala,

is on at Goldsmiths CCA, London, until 04 June 2023. Further details available

at:

www.goldsmithscca.art/exhibition/pilvi-takala

images

still images of video works

© Pilvi Takala 2023. Courtesy the artist; Carlos/Ishikawa,

London; and Stigter van Doesburg, Amsterdam.

installation images

Pilvi Takala: On Discomfort,

Goldsmiths CCA 2023. Photographs: Rob Harris.

publication date

12 April 2023

tags

Sophie Calle, Cosplay, Deloitte, Desk, Email, Film, Goldsmiths CCA, Mirror, Neoliberalism, Office, Tim Robinson, Roleplay, Second Home, Security, SelgasCano, Shopping centre, Pilvi Takala, Tea Dance, Touching, Venice Biennale, WhatsApp, Will Wiles, Workplace

www.goldsmithscca.art/exhibition/pilvi-takala

images