Aviva Studios in Manchester: a new type of cultural space

awaiting new cultural ideas

Aviva Studios, the newest arts space in the United Kingdom,

and home to Factory International, has landed in the historic centre of Manchester.

Designed by Ellen van Loon of Office for Metropolitan Architecture, it offers a

completely new form of creative space, which has potential to match its price

tag, but could also be a difficult space to learn and adapt to. Will Jennings

visited to see the building and Free Your Mind, the dance reimagination of The

Matrix which launched the building.

There can a delicate line between legacy and nostalgia, heritage and kitsch. Manchester, a city pushing forwards with skyscrapers, redevelopment, and new creativity, has undoubted built and cultural legacy, and with Aviva Studios, the nation’s newest and hugely expensive arts space, it seeks to play that fine balance. It lands like a spaceship into an historic part of the city – brick railway arches run right through its ground floor – but is tightly packed between shining new luxury apartments, and seeks to be a beacon for as-yet-uknown future creative ambition, while still recalling the spirit, grit, and local personality of the city’s cultural and industrial past.

![]()

![]()

Situated underneath and between a confluence of awkward infrastructure and residual spaces, its externality conceals internal spaces which are bewilderingly large and complex – a cavernous and complicated space found within a piece of the city leftover from market-led property development across the surrounding site. The sponsor-name Aviva Studios is just its latest incarnation, having previously been called The Factory and Factory International, both leaning upon the city’s foundational watermarks of the industrial revolution (of which some factory architecture can still be found around the city despite a dramatic cleansing and rebuilding of recent years), the New Order and Happy Mondays label Factory Records, and the previous amalgamation of Factory’s industry-infused Hacienda nightclub.

Ellen van Loon, architect at Dutch Rem Koolhaas-led firm Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), is the creative force behind the project which has come in not only several years late and far over budget, but also with a dramatically reimagined form from the 2015 competition winning design. That presented a glass-faced mass with a tent-like structure leaking from it (see OMA’s website), an external skin flung around an endlessly-variable and playful space within which any kind of imaginable (or, as-yet unknown) cultural form could be developed. It was straight out of Cedric Price and Joan Littlewood’s Fun Palace manifesto (see 00019) – though, similarly, was never constructed.

![]()

![]()

What has emerged is impressive, but complicated and value engineered. At its simplest, it is two main spaces: an enormous, rectangular black-box ‘warehouse’ 64m long, 33m wide, and with a ceiling some 21m from a ground floor that can hold 5000 standing people in an open configuration; and, conjoining the warehouse as the short edge of an L-shaped configuration, a traditional theatre auditorium with 1600 seats addressing a 22m wide proscenium which backs onto the larger space. Together, these can be used in a variety of configurations. They could be two separate spaces. The larger warehouse can be used in its entirety, as it was for the opening Yayoi Kusama exhibition presented as a precursor to the full opening (see 00109), while the theatre space could be used concurrently in its traditional format. The two can also combine, offering a theatre space with a proscenium with an extra 33m depth, into the void of the warehouse. Separately, the warehouse has the option of an acoustically-sealed dividing wall to split it in two, which could offer s cuboid void alongside either a slightly larger void and a theatre space, or a theatre with that deep proscenium. Still following?

For all the possible permutations the space permits, it basically boils down to two spaces of two typologies which can be subdivided into a possible three spaces of two typologies – far from the poetic freedom of an ever-changing as imagined by Price, idealised within the original plans. It might be that as-yet unknown creative ambitions design uses for the space which play with these two interlocking forms, and this is the ambition of John McGrath, Creative Director and Chief Executive, who hopes that the unquestioned creative scope and imagination of the ever-evolving Manchester International Festival (MiF) (see 00109) will flood throughout the halls and voids of Aviva Studios to bring experimental arts to the building as it has to the city since 2005.

![]()

![]()

It opens with Free Your Mind, a dance reimagining of The Matrix, led by an all-star team of Danny Boyle as director, with designer Es Devlin, costumes by Gareth Pugh, choreographer Kenrick Sandy, composer Michael Assante, and writer Sabrina Mahfouz. It’s a work which seeks to showcase the possibilities of the OMA building, but it doesn’t really free the space in the way it intends to free the mind. The first half is entirely contained within the theatrical space, starting from the focus of local-boy Alan Turing introducing notions of freedom, idea, expanse, and possibility from a 1950s TV set, slowly engulfed by dancers who open the drama up into a relentless set-piece of rhythm and movement.

Then, it abruptly ends. Where the architecture presumes a freedom of movement and creative opportunity of slipping and segueing between spaces, modes, ideas, and forms, here we resort to a traditional interval where visitors can load up from the bars and eateries as well as explore the interstitial spaces and pop-up Instagram moments created for the show.

![]()

![]()

It's worth mentioning that the interstitial moments of van Loon’s building do have potential. Externally, a new public plaza with architectural overhang protects from the rain and offers new vantages upon an infrastructural network at a knot of the River Irwell, the Ordsall Footbridge, a railway bridge, and its predecessor, a now-unused viaduct designed by George Stephenson for the world’s first passenger railway in 1830.

![]()

![]()

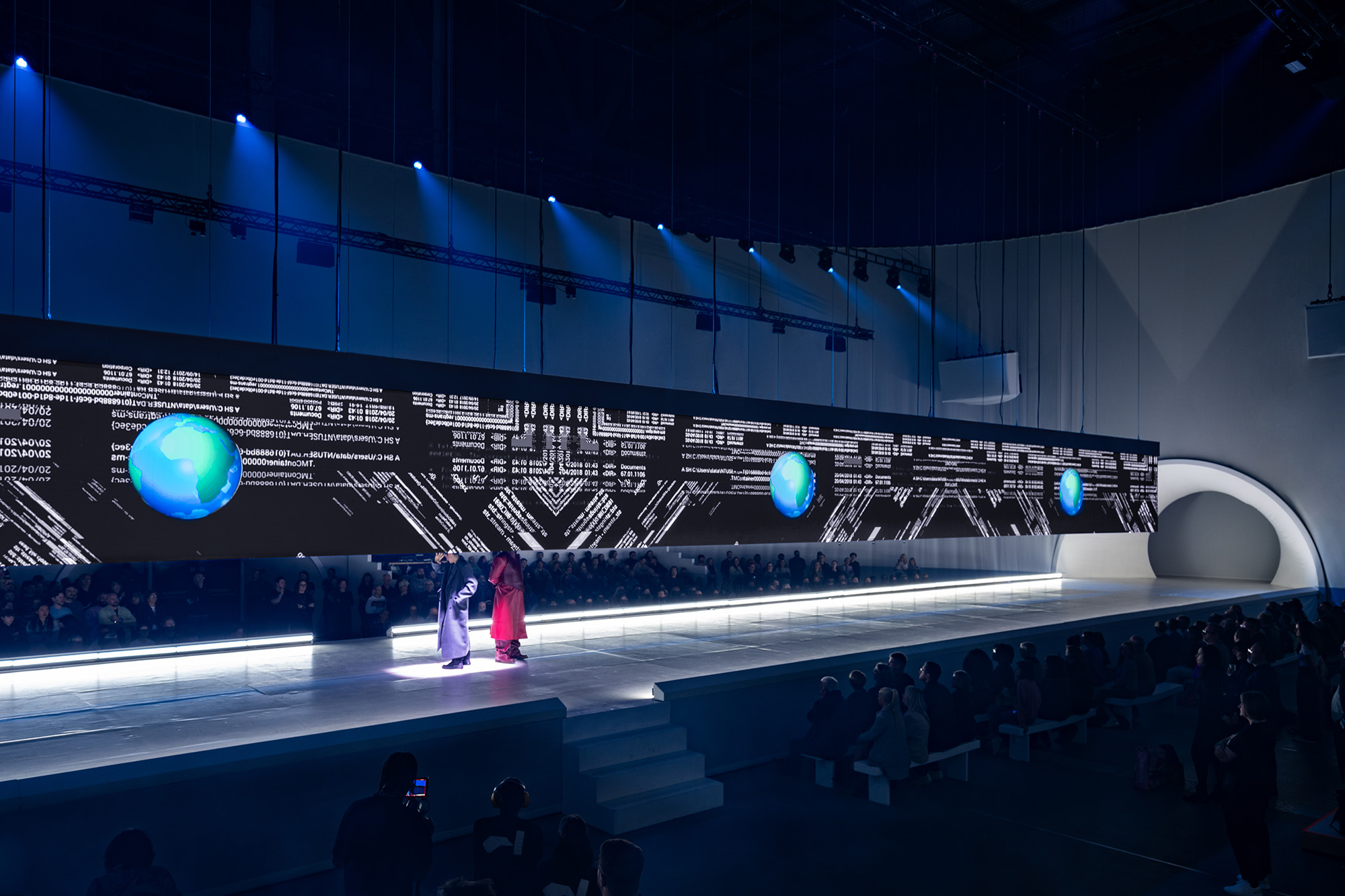

For now, however, it is all just future possibilities. The second half of Free Your Mind relocates the audience from the theatre into the Warehouse, with a Devlin-designed catwalk-like space running the length of the hall with immense drapes enclosing, and elongated video screens suspended over the stage. It begins with a city symphony of Manchester, compressing archive footage of looms, culture, streets, and people to the punchcard beat of New Order’s Blue Monday.

It’s spine-tingling, and prompts the audience to react in what seems like the real moment of launch for this most idiosyncratic of spaces, celebrating both the unique cultural architecture and the broader city and history it sits within. Then the rhythm fades, dancers enter, and it leaves the city-specificity to become a generic dance piece which – with heavy, broad brushes – speaks to our reliance upon technology, neoliberally independent consumption of culture, and desire for rewards from unknown digital strangers (at one point, a character dressed as a giant Facebook thumbs-up symbol walks down the catwalk – this is not a subtle work).

![]()

![]()

Free Your Mind may entirely fill the spatial expanse available, but it does not really speak to the creative possibilities of the architecture. Arguably, culture cannot be so much placed as presented with conditions to form, and so it may not be for some while yet that propositions and performances which really test Aviva Studios develop. This is the case with Manchester International Festival, the now globally-renowned event which seeps into the pores, crevices, abandoned spaces, and parks of the city allowing local and internationally regarded creatives to play, experiment, and develop new forms. It is the hope that what MiF has done to the city, it will do to the building – its new home, and HQ of Factory International, the production powerhouse that McGrath leads and sits behind the festival and programming of Aviva Studios.

However, there is concern that in folding and contorting the wide-ranging and exploratory festival into the confines of Aviva Studios might restrict the play, scope, and imagination it has become famed for. Though McGrath assures that the plans are for the festival to still seep into the city, find new spaces, audiences, and forms, the fact that there is now a huge building and expense to evidence through impressive cultural moments must surely change the centre of gravity of MiF. This building and its investment has to now show itself as worthy of the hundreds of millions of pounds expended upon it

![]()

![]()

Such embedded meaning in place will surely be a slow process. Though the modern metropolis was a flash in the pan – the city growing from a population of 10,000 in 1700 to a metropolis of 328,000 a century later – it is a place from which culture has gestated, grown, and then emerged more widely rather than with spectacular burst. The process of recognition of Joy Division which shifted into New Order was not a quick process. Oasis spent years playing in basements and bars before international stardom. Factory Records’ Hacienda itself, such a part of Aviva Studios’ DNA, was not really recognised for its cultural importance (other than to a knowing, local audience) until well after it had closed its doors.

The building that was once the Hacienda is now a block of luxury flats. Manchester has changed, as have the conditions and manners of cultural production. It is hard for an impromptu rave to take place in an 1870s factory, if all the factories have been cleared for skyscrapers or repurposed as heritage-themed apartments. It is hard for a band like Oasis to rehearse and emerge if there are no affordable musical studios, empty space to appropriate for creative play, or a political system which allows for the slowness of creative ambition to develop.

![]()

![]()

And this is the predicament of Aviva Studios. In the current economic and cultural economy, the £242m spent needs to show itself immediately with a bang. But that is not how culture works, and it especially isn’t how culture for such a nuanced and complicated proposition of the OMA building comes about. Free Your Mind is very much placed into the building, often awkwardly so, rather than emerging from it. These things take time, but will expectations, audiences, and budgets allow the time needed? The risk is that financial demands see more traditional blockbuster and touring shows slowly envelope the space at the expense of nuanced and experimental new programming which learns the building, both it’s possibilties and difficulties.

McGrath is so entwined with the vision and future of the project that one wonders what would happen should he decide to move to pastures new – any incomer would not only need to buy into the whole physical project, but also slowly develop new ways of filling and using it. There is, however, a vast team behind him that offers ingenuity, idea, ambition, and play, and it is unfair to judge a building of such Wagnerian intent and scale on its few opening stanzas. It takes a while to truly understand a score, story, and arc, and so the only fair way to critique a building beyond the aesthetic and formal qualities – and into the arguably more important developmental programme and output it fosters – is much later into its story.

Situated underneath and between a confluence of awkward infrastructure and residual spaces, its externality conceals internal spaces which are bewilderingly large and complex – a cavernous and complicated space found within a piece of the city leftover from market-led property development across the surrounding site. The sponsor-name Aviva Studios is just its latest incarnation, having previously been called The Factory and Factory International, both leaning upon the city’s foundational watermarks of the industrial revolution (of which some factory architecture can still be found around the city despite a dramatic cleansing and rebuilding of recent years), the New Order and Happy Mondays label Factory Records, and the previous amalgamation of Factory’s industry-infused Hacienda nightclub.

Ellen van Loon, architect at Dutch Rem Koolhaas-led firm Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), is the creative force behind the project which has come in not only several years late and far over budget, but also with a dramatically reimagined form from the 2015 competition winning design. That presented a glass-faced mass with a tent-like structure leaking from it (see OMA’s website), an external skin flung around an endlessly-variable and playful space within which any kind of imaginable (or, as-yet unknown) cultural form could be developed. It was straight out of Cedric Price and Joan Littlewood’s Fun Palace manifesto (see 00019) – though, similarly, was never constructed.

What has emerged is impressive, but complicated and value engineered. At its simplest, it is two main spaces: an enormous, rectangular black-box ‘warehouse’ 64m long, 33m wide, and with a ceiling some 21m from a ground floor that can hold 5000 standing people in an open configuration; and, conjoining the warehouse as the short edge of an L-shaped configuration, a traditional theatre auditorium with 1600 seats addressing a 22m wide proscenium which backs onto the larger space. Together, these can be used in a variety of configurations. They could be two separate spaces. The larger warehouse can be used in its entirety, as it was for the opening Yayoi Kusama exhibition presented as a precursor to the full opening (see 00109), while the theatre space could be used concurrently in its traditional format. The two can also combine, offering a theatre space with a proscenium with an extra 33m depth, into the void of the warehouse. Separately, the warehouse has the option of an acoustically-sealed dividing wall to split it in two, which could offer s cuboid void alongside either a slightly larger void and a theatre space, or a theatre with that deep proscenium. Still following?

For all the possible permutations the space permits, it basically boils down to two spaces of two typologies which can be subdivided into a possible three spaces of two typologies – far from the poetic freedom of an ever-changing as imagined by Price, idealised within the original plans. It might be that as-yet unknown creative ambitions design uses for the space which play with these two interlocking forms, and this is the ambition of John McGrath, Creative Director and Chief Executive, who hopes that the unquestioned creative scope and imagination of the ever-evolving Manchester International Festival (MiF) (see 00109) will flood throughout the halls and voids of Aviva Studios to bring experimental arts to the building as it has to the city since 2005.

It opens with Free Your Mind, a dance reimagining of The Matrix, led by an all-star team of Danny Boyle as director, with designer Es Devlin, costumes by Gareth Pugh, choreographer Kenrick Sandy, composer Michael Assante, and writer Sabrina Mahfouz. It’s a work which seeks to showcase the possibilities of the OMA building, but it doesn’t really free the space in the way it intends to free the mind. The first half is entirely contained within the theatrical space, starting from the focus of local-boy Alan Turing introducing notions of freedom, idea, expanse, and possibility from a 1950s TV set, slowly engulfed by dancers who open the drama up into a relentless set-piece of rhythm and movement.

Then, it abruptly ends. Where the architecture presumes a freedom of movement and creative opportunity of slipping and segueing between spaces, modes, ideas, and forms, here we resort to a traditional interval where visitors can load up from the bars and eateries as well as explore the interstitial spaces and pop-up Instagram moments created for the show.

It's worth mentioning that the interstitial moments of van Loon’s building do have potential. Externally, a new public plaza with architectural overhang protects from the rain and offers new vantages upon an infrastructural network at a knot of the River Irwell, the Ordsall Footbridge, a railway bridge, and its predecessor, a now-unused viaduct designed by George Stephenson for the world’s first passenger railway in 1830.

Internally, the entire ground floor is an open space with

moveable furniture and a central podium which could be used as a DJ booth,

speaking to the general aesthetic and vibe, designed by Ben Kelly, creator of the singular and seminal Hacienda aesthetic, here trying to find the balance beteween kitsch and heritage. There are also spaces leading

away and around from here: escalators and staircases lead to mezzanines; generous

toilets interject into the historic brick arches that cut through the site, and

are so large even have potential to be appropriated as an event space in their

own right; and a cut-through will eventually lead from Aviva Studios into the

adjoining Science and Industry Museum, offering an exciting potential mix of

audiences as well as a hope of cultural and curatorial interdisciplinary

experimentation.

For now, however, it is all just future possibilities. The second half of Free Your Mind relocates the audience from the theatre into the Warehouse, with a Devlin-designed catwalk-like space running the length of the hall with immense drapes enclosing, and elongated video screens suspended over the stage. It begins with a city symphony of Manchester, compressing archive footage of looms, culture, streets, and people to the punchcard beat of New Order’s Blue Monday.

It’s spine-tingling, and prompts the audience to react in what seems like the real moment of launch for this most idiosyncratic of spaces, celebrating both the unique cultural architecture and the broader city and history it sits within. Then the rhythm fades, dancers enter, and it leaves the city-specificity to become a generic dance piece which – with heavy, broad brushes – speaks to our reliance upon technology, neoliberally independent consumption of culture, and desire for rewards from unknown digital strangers (at one point, a character dressed as a giant Facebook thumbs-up symbol walks down the catwalk – this is not a subtle work).

Free Your Mind may entirely fill the spatial expanse available, but it does not really speak to the creative possibilities of the architecture. Arguably, culture cannot be so much placed as presented with conditions to form, and so it may not be for some while yet that propositions and performances which really test Aviva Studios develop. This is the case with Manchester International Festival, the now globally-renowned event which seeps into the pores, crevices, abandoned spaces, and parks of the city allowing local and internationally regarded creatives to play, experiment, and develop new forms. It is the hope that what MiF has done to the city, it will do to the building – its new home, and HQ of Factory International, the production powerhouse that McGrath leads and sits behind the festival and programming of Aviva Studios.

However, there is concern that in folding and contorting the wide-ranging and exploratory festival into the confines of Aviva Studios might restrict the play, scope, and imagination it has become famed for. Though McGrath assures that the plans are for the festival to still seep into the city, find new spaces, audiences, and forms, the fact that there is now a huge building and expense to evidence through impressive cultural moments must surely change the centre of gravity of MiF. This building and its investment has to now show itself as worthy of the hundreds of millions of pounds expended upon it

Such embedded meaning in place will surely be a slow process. Though the modern metropolis was a flash in the pan – the city growing from a population of 10,000 in 1700 to a metropolis of 328,000 a century later – it is a place from which culture has gestated, grown, and then emerged more widely rather than with spectacular burst. The process of recognition of Joy Division which shifted into New Order was not a quick process. Oasis spent years playing in basements and bars before international stardom. Factory Records’ Hacienda itself, such a part of Aviva Studios’ DNA, was not really recognised for its cultural importance (other than to a knowing, local audience) until well after it had closed its doors.

The building that was once the Hacienda is now a block of luxury flats. Manchester has changed, as have the conditions and manners of cultural production. It is hard for an impromptu rave to take place in an 1870s factory, if all the factories have been cleared for skyscrapers or repurposed as heritage-themed apartments. It is hard for a band like Oasis to rehearse and emerge if there are no affordable musical studios, empty space to appropriate for creative play, or a political system which allows for the slowness of creative ambition to develop.

And this is the predicament of Aviva Studios. In the current economic and cultural economy, the £242m spent needs to show itself immediately with a bang. But that is not how culture works, and it especially isn’t how culture for such a nuanced and complicated proposition of the OMA building comes about. Free Your Mind is very much placed into the building, often awkwardly so, rather than emerging from it. These things take time, but will expectations, audiences, and budgets allow the time needed? The risk is that financial demands see more traditional blockbuster and touring shows slowly envelope the space at the expense of nuanced and experimental new programming which learns the building, both it’s possibilties and difficulties.

McGrath is so entwined with the vision and future of the project that one wonders what would happen should he decide to move to pastures new – any incomer would not only need to buy into the whole physical project, but also slowly develop new ways of filling and using it. There is, however, a vast team behind him that offers ingenuity, idea, ambition, and play, and it is unfair to judge a building of such Wagnerian intent and scale on its few opening stanzas. It takes a while to truly understand a score, story, and arc, and so the only fair way to critique a building beyond the aesthetic and formal qualities – and into the arguably more important developmental programme and output it fosters – is much later into its story.

Aviva Studios, the home of Factory International, is

a landmark new cultural space for Manchester and the world. Built with

flexibility in mind, the design of the building is led by Ellen van Loon of the

world-leading practice Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). The

multi-use space can adapt to host any kind of set-up — from intimate theatre

shows and intricate exhibitions, to huge multimedia performances and

warehouse-scale gigs fit for the greatest artists of our time. Its development

is led by Manchester City Council, with backing from HM Government and Arts

Council England.

www.factoryinternational.org/aviva-studios

Factory International builds on the legacy of

Manchester International Festival, one of the world’s leading arts festivals,

and the first to be entirely focused on the commissioning and producing of

ambitious new work. Staged every two years in Manchester since 2007, MIF has

commissioned, produced and presented world premieres by artists including

Marina Abramović, Damon Albarn, Laurie Anderson, Björk, Boris Charmatz, Jeremy

Deller, Idris Elba and Kwame Kwei-Armah, Elbow, Tracey Emin, Akram Khan, David

Lynch, Ibrahim Mahama, Wayne McGregor, Steve McQueen, Marta Minujín, Cillian

Murphy, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, Yoko Ono, Thomas Ostermeier, Maxine Peake,

Punchdrunk, Skepta, Christine Sun Kim, The xx, and Robert Wilson.

These and other world-renowned artists from different art

forms and backgrounds create dynamic, innovative and forward-thinking new work

reflecting the spectrum of performing arts, visual arts and popular culture,

staged across Greater Manchester – from theatres, galleries and concert halls

to railway depots, churches and car parks. Working closely with cultural

organisations globally, whose financial and creative input helps to make many

of these projects possible, much of the work made at MIF also goes on to travel

the world, reaching an audience of 1.8 million people in more than 30 countries

to date.

www.factoryinternational.org

Ellen van Loon is Partner at OMA. She joined the

office in 1998 and has led award-winning building projects that combine

sophisticated design with precise execution. Her recently completed projects

include Jacquemus' shops in London and Paris (2022), Tiffany & Co's

temporary showroom in Doha (2023) and temporary store on Avenue Montaigne

(2022) in Paris, the BVLGARI Fine Jewelry Show in Milan (2021), Brighton

College in Brighton (2020), BLOX / DAC in Copenhagen (2018), Rijnstraat 8 in

The Hague (2017), and Lab City CentraleSupélec (2017). Other projects in her

portfolio include Fondation Galeries Lafayette (2018) in Paris; Qatar National

Library (2017); Amsterdam’s G-Star Raw Headquarters (2014); De Rotterdam, the

largest building in the Netherlands (2013); CCTV Headquarters in Beijing

(2012); New Court Rothschild Bank in London (2011); Maggie's Centre in Glasgow

(2011); Casa da Musica in Porto (2005) – winner of the 2007 RIBA Award; and the

Dutch Embassy in Berlin (2003) – winner of the European Union Mies van der Rohe

Award in 2005.

Ellen van Loon is currently working on the transformation of

Kaufhaus des Westens (KaDeWe) Berlin – Europe’s biggest department store;

Lamarr, a new store for the KaDeWe Group in Vienna; and the Palais de Justice

de Lille.

www.oma.com/partners/ellen-van-loon

John McGrath was appointed in 2015 to lead Manchester

International Festival (MIF) as Artistic Director and Chief Executive, and the

development of its new building, John McGrath has since curated three

festivals, as well as leading the vision and strategy for Factory

International’s new venue, Aviva Studios. Under John, MIF has built on its

reputation for commissioning extraordinary work from the world’s great artists,

while also forming ever-deeper relationships with Manchester’s many

communities. Artists commissioned by John for the Festival include New Order

and Liam Gillick, Yoko Ono, David Lynch, Philip Glass and Phelim McDermott,

Laurie Anderson, Maxine Peake and Sarah Frankcom, Idris Elba and Kwame

Kwei-Armah, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, Ibrahim Mahama, Tania Bruguera and Marta

Minujín.

Prior to MIF, John was the founding Artistic Director of

National Theatre Wales, commissioning landmark site-specific work such as

Michael Sheen’s The Passion of Port Talbot and Mike Pearson’s The Persians.

Shows directed for National Theatre Wales include the award-winning The

Radicalisation of Bradley Manning. Previous roles include Artistic Director of

Contact, where John led the re-opening of the venue, and its re-focus on young

people as decision-makers, and Associate Director at legendary New York experimental

company Mabou Mines. Awards include NESTA Cultural Leadership Fellowship, and

Honorary Doctorate from the Open University. Publications include ‘Loving Big

Brother: Performance, Privacy and Surveillance Space’ (Routledge 2004).

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

These and other world-renowned artists from different art forms and backgrounds create dynamic, innovative and forward-thinking new work reflecting the spectrum of performing arts, visual arts and popular culture, staged across Greater Manchester – from theatres, galleries and concert halls to railway depots, churches and car parks. Working closely with cultural organisations globally, whose financial and creative input helps to make many of these projects possible, much of the work made at MIF also goes on to travel the world, reaching an audience of 1.8 million people in more than 30 countries to date.

www.factoryinternational.org

Ellen van Loon is Partner at OMA. She joined the office in 1998 and has led award-winning building projects that combine sophisticated design with precise execution. Her recently completed projects include Jacquemus' shops in London and Paris (2022), Tiffany & Co's temporary showroom in Doha (2023) and temporary store on Avenue Montaigne (2022) in Paris, the BVLGARI Fine Jewelry Show in Milan (2021), Brighton College in Brighton (2020), BLOX / DAC in Copenhagen (2018), Rijnstraat 8 in The Hague (2017), and Lab City CentraleSupélec (2017). Other projects in her portfolio include Fondation Galeries Lafayette (2018) in Paris; Qatar National Library (2017); Amsterdam’s G-Star Raw Headquarters (2014); De Rotterdam, the largest building in the Netherlands (2013); CCTV Headquarters in Beijing (2012); New Court Rothschild Bank in London (2011); Maggie's Centre in Glasgow (2011); Casa da Musica in Porto (2005) – winner of the 2007 RIBA Award; and the Dutch Embassy in Berlin (2003) – winner of the European Union Mies van der Rohe Award in 2005.

Ellen van Loon is currently working on the transformation of Kaufhaus des Westens (KaDeWe) Berlin – Europe’s biggest department store; Lamarr, a new store for the KaDeWe Group in Vienna; and the Palais de Justice de Lille.

www.oma.com/partners/ellen-van-loon

John McGrath was appointed in 2015 to lead Manchester International Festival (MIF) as Artistic Director and Chief Executive, and the development of its new building, John McGrath has since curated three festivals, as well as leading the vision and strategy for Factory International’s new venue, Aviva Studios. Under John, MIF has built on its reputation for commissioning extraordinary work from the world’s great artists, while also forming ever-deeper relationships with Manchester’s many communities. Artists commissioned by John for the Festival include New Order and Liam Gillick, Yoko Ono, David Lynch, Philip Glass and Phelim McDermott, Laurie Anderson, Maxine Peake and Sarah Frankcom, Idris Elba and Kwame Kwei-Armah, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, Ibrahim Mahama, Tania Bruguera and Marta Minujín.

Prior to MIF, John was the founding Artistic Director of National Theatre Wales, commissioning landmark site-specific work such as Michael Sheen’s The Passion of Port Talbot and Mike Pearson’s The Persians. Shows directed for National Theatre Wales include the award-winning The Radicalisation of Bradley Manning. Previous roles include Artistic Director of Contact, where John led the re-opening of the venue, and its re-focus on young people as decision-makers, and Associate Director at legendary New York experimental company Mabou Mines. Awards include NESTA Cultural Leadership Fellowship, and Honorary Doctorate from the Open University. Publications include ‘Loving Big Brother: Performance, Privacy and Surveillance Space’ (Routledge 2004).