A new way of seeing: Thomas Huber’s landscapes

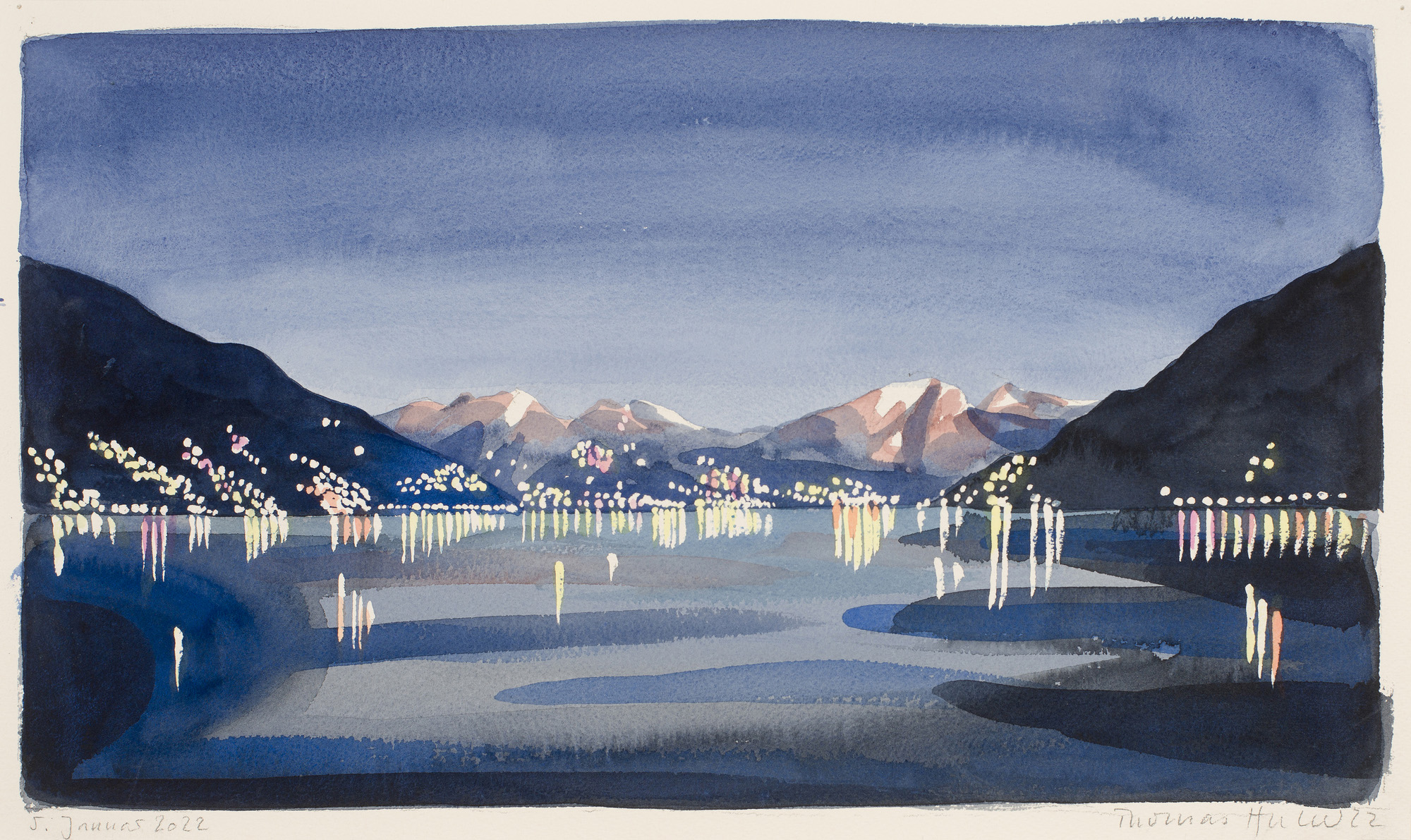

An exhibition at MASI Lugano presents a large new body of work from painter Thomas Huber, an artist known for depicting architecture turns his eye to Swiss & Italian mountains surrounding Lake Lugano. Robert Barry immersed himself in the landscapes & spoke to the artist about his new way of seeing.

Thomas Huber wanted the mountains to paint themselves. He had

returned to these territories, amongst the great alpine lakes on the border

between Switzerland and Italy, in search of some sort of homecoming, a

reminiscence of his childhood home in the mountains above Lake Lugano. What he

found was something quite different: a new way of seeing.

“I started really to observe the surroundings,” Huber told me when we spoke recently. “I noticed, for instance, in the evening time, when the sunset started, that the shadows of the mountains behind me were projected. The mountains projected their shadows onto the mountains in front of me, so the mountains were reflecting their own image on another mountain.” It was as though nature were depicting itself in real time, fashioning its own representation. “I started trying to draw that and to paint it with aquarelles,” Huber continues, “but it didn’t work. I couldn’t do that. That started the whole thing.”

![]()

![]()

The whole thing in question is an exhibition of seventy new works currently on display at the Museo d’arte della Svizzera Italiana (MASI) in Lugano. Collectively, the works mark a new direction and a new chapter in the artist’s oeuvre. The show is called Lago Maggiore and it takes inspiration from the view from the house Huber bought four years ago overlooking the eponymous lake just forty-odd kilometres from here down the Cassarate river.

Growing up in a family of architects (his mother worked with Le Corbusier and Jean Prouvé), Huber is known principally for his paintings of buildings. Classic works like Rede in der Schule (1983) and Große Rauten (2005) presented surreal-looking architectures recalling De Chirico and Piranesi. For the most part, such man-made structures are absent here, with the painter’s gaze focused instead on the eponymous lake and surrounding peaks. These natural forms are rendered first in hastily sketched watercolours on paper, notable for their rapid brushstrokes and painterly, almost impressionistic appearance; later, in much larger oil paintings with a far flatter, smoother surface and cooler overall style (both are included in the show).

Sometimes the titles give a hint towards the lapse of time between the two. One of the oils, for instance, is titled 20.6.17 but dated 2021. Other times, you won’t find one particular aquarelle sketch to correspond to a later oil on canvas, but you get the sense that two or more sketches have led to a single painting, as if Huber were trying to obtain, from a number of preliminary studies, something like the essence of eveningness or autumnness.

![]()

![]()

The paintings, then, are more synthetic than naturalistic. With their bright colours and swirling shapes, they remind me of the graphic images on advertising posters promoting alpine resorts that I recall seeing on family holidays as a child. Here and there, you’ll also notice the strong influence of Ferdinand Hodler and Félix Vallotton, placing Huber in a peculiarly Swiss tradition of landscape painters. But if we compare the images down here in the basement with some of the works from MASI’s main collection upstairs – like Hodler’s Die Waadtländer Alpen von des Rochers de Naye aus, Richard Seewald’s Mädchen auf dem Balkon, Luigi Rossi’s Il sogno del pescatore, and Mariane von Werefkin’s Il Ticino, all local lake and mountain-scapes – though certain similarities in technique and framing can be drawn, what suddenly becomes striking is the complete absence of any human figures in Huber’s paintings. It’s as if the artist is leaving room for you, the viewer (some of the pictures even contain an empty bench looking out over the lake, quite similar to the benches dotted around the gallery).

I say ‘for the most part’ because in a few of these works we seem to have taken a step back, from the view itself to the room and the open window through which it’s been viewed. In one painting, for example, Wilmas Zimmer (2022), we find ourselves in apricot-coloured room. We can see a patterned rug on the floor, the corner post of a bed, its sheets rumpled from being slept in, one end of a chaise longue. And at the far end of the room, centre frame, an open door revealing a view of the lake and the mountains much like those filling the other paintings here in the gallery. There is also a framed picture on the wall of the room in this picture (and its wooden frame is almost identical to the door jamb). Then, on the wall next to the door, there is a mirror (with a rather more ornate frame) which reflects the image of another framed picture (or possibly another small window). There are frames within frames within frames within frames. After seeing this painting, it’s impossible not to see the implied window frame around all the other paintings, the frame the gallery infrastructure provides for the whole show – and perhaps also to start to see the mountains themselves as a frame around the oleaginous play of colours on the lake, too.

![]()

![]()

Huber demurred at my suggestion of this as some sort of analogy. “The lake is something like a metaphor for myself,” he insisted, “because it also reflects the landscape, so it’s doing the same thing as I do.” He was keener to draw my attention to the way the diagonals of the mountainsides draw your focus into the middle of the frame, explaining that “these things are very important to create an image.”

“When I started my career as an artist,” he continues, “I was aways wondering what it is about a painting: what does a painting mean, what is the reason of a painting? And finally, if I look now at these landscapes, I would say, the meaning is just in the contemplation. The painting is done if you can look at it. If you can look a long time at it.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

“I started really to observe the surroundings,” Huber told me when we spoke recently. “I noticed, for instance, in the evening time, when the sunset started, that the shadows of the mountains behind me were projected. The mountains projected their shadows onto the mountains in front of me, so the mountains were reflecting their own image on another mountain.” It was as though nature were depicting itself in real time, fashioning its own representation. “I started trying to draw that and to paint it with aquarelles,” Huber continues, “but it didn’t work. I couldn’t do that. That started the whole thing.”

Fig.i,ii

The whole thing in question is an exhibition of seventy new works currently on display at the Museo d’arte della Svizzera Italiana (MASI) in Lugano. Collectively, the works mark a new direction and a new chapter in the artist’s oeuvre. The show is called Lago Maggiore and it takes inspiration from the view from the house Huber bought four years ago overlooking the eponymous lake just forty-odd kilometres from here down the Cassarate river.

Growing up in a family of architects (his mother worked with Le Corbusier and Jean Prouvé), Huber is known principally for his paintings of buildings. Classic works like Rede in der Schule (1983) and Große Rauten (2005) presented surreal-looking architectures recalling De Chirico and Piranesi. For the most part, such man-made structures are absent here, with the painter’s gaze focused instead on the eponymous lake and surrounding peaks. These natural forms are rendered first in hastily sketched watercolours on paper, notable for their rapid brushstrokes and painterly, almost impressionistic appearance; later, in much larger oil paintings with a far flatter, smoother surface and cooler overall style (both are included in the show).

Sometimes the titles give a hint towards the lapse of time between the two. One of the oils, for instance, is titled 20.6.17 but dated 2021. Other times, you won’t find one particular aquarelle sketch to correspond to a later oil on canvas, but you get the sense that two or more sketches have led to a single painting, as if Huber were trying to obtain, from a number of preliminary studies, something like the essence of eveningness or autumnness.

Fig.iii,iv

The paintings, then, are more synthetic than naturalistic. With their bright colours and swirling shapes, they remind me of the graphic images on advertising posters promoting alpine resorts that I recall seeing on family holidays as a child. Here and there, you’ll also notice the strong influence of Ferdinand Hodler and Félix Vallotton, placing Huber in a peculiarly Swiss tradition of landscape painters. But if we compare the images down here in the basement with some of the works from MASI’s main collection upstairs – like Hodler’s Die Waadtländer Alpen von des Rochers de Naye aus, Richard Seewald’s Mädchen auf dem Balkon, Luigi Rossi’s Il sogno del pescatore, and Mariane von Werefkin’s Il Ticino, all local lake and mountain-scapes – though certain similarities in technique and framing can be drawn, what suddenly becomes striking is the complete absence of any human figures in Huber’s paintings. It’s as if the artist is leaving room for you, the viewer (some of the pictures even contain an empty bench looking out over the lake, quite similar to the benches dotted around the gallery).

I say ‘for the most part’ because in a few of these works we seem to have taken a step back, from the view itself to the room and the open window through which it’s been viewed. In one painting, for example, Wilmas Zimmer (2022), we find ourselves in apricot-coloured room. We can see a patterned rug on the floor, the corner post of a bed, its sheets rumpled from being slept in, one end of a chaise longue. And at the far end of the room, centre frame, an open door revealing a view of the lake and the mountains much like those filling the other paintings here in the gallery. There is also a framed picture on the wall of the room in this picture (and its wooden frame is almost identical to the door jamb). Then, on the wall next to the door, there is a mirror (with a rather more ornate frame) which reflects the image of another framed picture (or possibly another small window). There are frames within frames within frames within frames. After seeing this painting, it’s impossible not to see the implied window frame around all the other paintings, the frame the gallery infrastructure provides for the whole show – and perhaps also to start to see the mountains themselves as a frame around the oleaginous play of colours on the lake, too.

Fig.v,vi

Huber demurred at my suggestion of this as some sort of analogy. “The lake is something like a metaphor for myself,” he insisted, “because it also reflects the landscape, so it’s doing the same thing as I do.” He was keener to draw my attention to the way the diagonals of the mountainsides draw your focus into the middle of the frame, explaining that “these things are very important to create an image.”

“When I started my career as an artist,” he continues, “I was aways wondering what it is about a painting: what does a painting mean, what is the reason of a painting? And finally, if I look now at these landscapes, I would say, the meaning is just in the contemplation. The painting is done if you can look at it. If you can look a long time at it.”

Figs.vii-x

Thomas Huber, born in Zurich, comes from a family of architects, studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Basel from 1977 to 1978, before continuing his training at the Royal College of Art in London in 1979 and the Staatliche Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf from 1980 to 1983. In 1984 Kasper König invited him to Düsseldorf, to take part in the group show "Von hier aus" (From here on), which brought him international recognition. Since then, his works have been exhibited in major international institutions and museums such as Centre Pompidou in Paris (1988), Kunsthaus in Zurich (1993), Fundación Joan Miró in Barcelona (2002), Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam (2004), Aargauer Kunsthaus in Aarau (2004), MAMCO in Geneva (2012), Kunstmuseum in Bonn (2016), and MONA in Hobart (2017). From 1992 to 1999 he taught at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Braunschweig, and in 1992 he became temporary director of the Centraal Museum in Utrecht. From 2000 to 2002 he was president of the Deutscher Künstlerbund. He has received numerous awards, including the Kiefer Hablitzel prize (1984), the Zurich Kunstgesellschaft prize for young Swiss artists (1993), the Heitland Foundation prize (2004) and the Meret Oppenheim Prize (2013). In 2023 his project Dawn/Dusk was selected for the Art Unlimited section of Art Basel.

MASI Lugano (Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana) was established in 2015, when two long-standing Lugano museums - the Museo Cantonale d’Arte and Museo d’Arte della Città di Lugano – merged.

Thanks to its strategic position, at this cultural crossroads between the north and south of the Alps, MASI Lugano has quickly become one of the most popular art museums in Switzerland.

In its two venues – the modern LAC cultural centre and the historical Palazzo Reali – MASI hosts /presents a packed programme of temporary shows and ever-changing exhibitions devoted to the works in its collection. It offers a wide range of mediation activities in multiple languages, upholding the values of inclusion and accessibility. MASI is committed to providing a participatory, engaging museum experience for all. Its artistic scope is expanded by its partnership with the Giancarlo and Danna Olgiati Collection - part of the MASI circuit – which is entirely dedicated to modern and contemporary art.

www.masilugano.ch

Robert Barry is a freelance writer and musician based in London. His most recent book, Compact Disc, was published by Bloomsbury in 2020.

www.writingbyrobertbarry.tumblr.com

www.masilugano.ch