Hugh Pearman on writing About Buildings

In his new book, About Buildings, published by Yale University Press, architectural journalist Hugh Pearman guides the reader on a journey of the history of the built world through 55 carefully chosen case studies. Here, he speaks about the process of selecting which made the cut & why, sharing some thoughts on cultural buildings along the way.

Academics and writers have spent their entire careers working

to shed light upon and open up tiny details and ideas in architecture. So, it’s

no easy feat to present the history of architecture in a single book, thought

that is exactly what journalist Hugh Pearman has attempted with About

Buildings, published by Yale University Press.

Plotting a trajectory across the story of architecture from antiquity to the 21st century, Pearman breaks the story down into 11 thematic chapters and 55 buildings (and some landscapes), with digestible case studies which join together to present a whistlestop yet illuminating race through architectural history. All written, he says, “with absolutely none of that archibabble.”

“The selection was key, which is why these rules emerge,” Pearman says of a series of undeclared editorial rules which informed his selection, three of which are: “Only one building per named architect, only five examples of each type, and it must still exist.” Before these rules were imposed, it could have grown into a much larger beast: “Originally it was going to be twice as big – eleven types could have been thirty, or I could have had ten case studies for each, not five. But it would have taken me another five years… so I'm quite glad.”

These rules prevent the book turning into predictable repeat of the white male canon of architects from all textbooks and one which offers a delightful array of studied and celebrated projects alongside the unexpected. Langham Place Shopping Mall, for example, is a 2004 “nondescript, 15-storeys building” in Mong Kok, Hong Kong, designed by Jon Jerde. It is an architecture, however, that speaks to the modern world of consumerism, but while not iconic or aesthetically remarkable, to Pearman is fascinating through it’s context and symbolism. “Mong Kok is a quite astonishing place – it was the inspiration for Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, a seething commercial centre out of which this tower erupts, surrounded by tiny alleyways.” For similar reasons, but with an entirely different aesthetic, Chetwoods-designed Magna Park, a series of vast Amazon distribution warehouses in the Milton Keynes countryside.

![]()

![]()

That such projects are present illustrates that About Buildings is not designed to be a list of iconic starchitect-designed showpieces: “I am avoiding a lot of the showy stuff. I'm avoiding Bjarke Ingels and so on, it can tend to dominate, and I'm quite fond of good, ordinary, more pragmatic buildings – I think that landmarks can look after themselves!” That said, the obvious big names do make an appearance: “There had to be a Mies van der Rohe, a Frank Lloyd Wright and a Le Corbusier.”

“I wrote about 10% more buildings that were included,” Pearman says, adding that with the rules of one-building-per-designer they had to get culled. Mies’s Seagram Building in New York, for example, made way for his Villa Tugendhat in Czechia. There were many from Le Corbusier to choose from, but Pearman plumped for Notre Dame du Haut, his chapel at Ronchamp. “It completely blew me away – it was an obvious example to have,” Pearman says, though he has not been to every building in the book: “These days our lives have been transformed by Google Earth and Street View, they’re just so incredibly useful to get an idea of the surroundings – it’s not the same as going to see a building but often, and certainly with cultural buildings, people have photographed the inside.”

![]()

![]()

fig.iii - About Buildings spread featuring Johnson Wax Headquarters. fig.iv - Villa Tugendhat

The two themed chapters on Museums and Performance will interest readers of recessed.space. Here, Pearman compresses the history of cultural architecture into five case studies – though in chapter introductions he always manages to squeeze in a few other references to broaden the discussion, such as a discussion of Andrea Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico in the Performance chapter. “For instance,” he adds, “I thought how can I not have Lina Bo Bardi, so she's the intro to culture building section but she's not one of the case studies – I was trying to cheat by trying to get lots more buildings into the intros.”

The Bo Bardi building mentioned is her São Paulo Museum of Modern Art, included in the introduction to the Museums section in an introductory text which starts with Elias Ashmole, who in 1683 transferred 26 wooden chests containing is eclectic collection of worldly objects from London to Oxford. Once unpacked, they formed the basis of the world’s first purpose-built museum, the Ashmolean.

“It all comes down to stuff in boxes. Obviously, the British Museum is a prime example because it also started from the personal collection of Hans Sloane – I think that we need nerds to collect stuff don't we? If you go to any museum it seems like it’s all nerds specialising in some sort of thing just getting their boxes together.”

![]()

![]()

Now, however, the boxes are grander and larger than ever before. Museums and cultural buildings now are perhaps more akin to the Amazon warehouses than any other type of place in the book. In a way, Pearman says, this is at the root of the book from synopsis stage, wondering “why do buildings look different from each other? Not because of style, or because of geography, but just because of their uses. Why does a theatre look different to a factory?” He continues with an example, “In fact, the big museums now are actually factories, look at all the set design taking place in the Royal Opera House for example, they've got conveyor belts and machinery.”

Manchester’s Aviva Studios (see 00147) by OMA – who do make an entry with the CCTV building in Beijing – was finished too late for inclusion in About Buildings, but it speaks to Pearman’s interests. “I went to it and thought that it was very meta – we used to do culture in found industrial spaces, so they made a new building which looks like a found industrial space. I can understand the logic of that actually, although it’s a masterwork of value engineering! But you'd never have this in London, there's some kind of Manchester-ey thing going on.”

The five selected museums are the Uffizi (1583) by Giorgio Vasari and Bernardo Buontalenti, John Soane’s Dulwich Picture Gallery (1814), the Pompidou Centre (1977) by Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, and Gianfranco Franchini, Ningbo History Museum (2008) by Amateur Architecture Studio, and David Adjaye’s Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (2016).

![]()

![]()

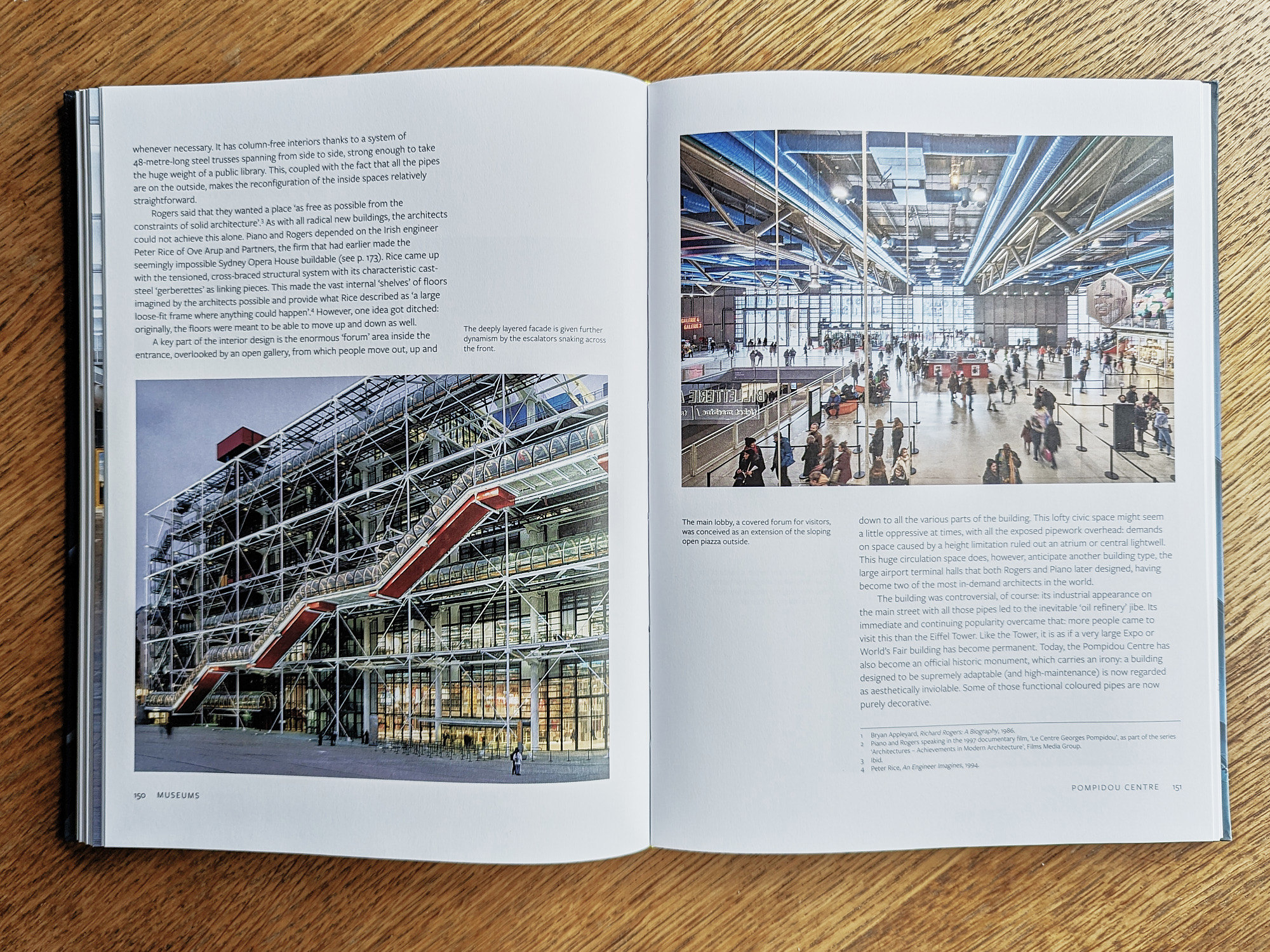

fig.vii - About Buildings spread featuring the Pompidou Centre. fig.viii - Tugendhat Villa

There are, you can see, many omissions enforced by the editorial rules. No Zaha Hadid, for example, who perhaps fell into the “showy stuff” category, but Pearman nearly included MAXXI Museum in Rome: “I'm more forgiving of MAXXI, because I think it was the last Zaha building that was pretty much hand drawn, as opposed to using Patrik Schumacher’s computers.”

Another starchitect, Frank Gehry, did make the cut with the Performance section including leading up to his LA Walt Disney Concert Hall (2003), having already toured through: the Theatre at Epidauros (4th century BCE) by Polykleitos the Younger; the 1997 rebuild of Richard Burbage’s 1614 Globe Theatre by Theo Crosby, Peter Street, and John Orrell; the Bayreuth Festspielhaus (1876) by Richard Wagner, Gottfried Semper, Otto Brückwald, and Carl Brandt; and the Sydney Opera House (1973) by Jørn Utzon.

“I featured it rather than the Guggenheim Bilbao,” Pearman explains, “which is another obviously missing one from the book. Because it is one building per architect, I thought I'd go for Walt Disney because although it was a little later than the Guggenheim but was designed before it.” Gehry is clearly an architect who can be included in the “showy stuff” category, and also divides opinions like few others. “I do get disarmed by Gehry. I know I shouldn't, but I do go wanting to hate a building and then I end up thinking, ‘oh Frank, you old rascal, you!’” Pearman says, adding “the one I visited expecting to hate and came away going, ‘oh, you've done it again,’ was the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Bois de Boulogna, Paris. There's all the usual acres of leftover space and it's really crude because Gehry doesn’t do fine details – and I rather loved it!”

![]()

![]()

Across the 55 places eloquently described and discussed in About Buildings, there will be many which similarly divide the reader. Across all periods and typologies there will be designs and ideas which disgust as well as delight, but this is not a coffee table book of aesthetic titillation, despite a rich selection of images throughout. About Buildings is a guidebook across the globe and into the past, taking the reader not only into buildings they may never visit in the flesh, but into the stories and meaning behind them also. Pearman is an excellent guide.

![]()

fig.xi - About Buildings cover

Plotting a trajectory across the story of architecture from antiquity to the 21st century, Pearman breaks the story down into 11 thematic chapters and 55 buildings (and some landscapes), with digestible case studies which join together to present a whistlestop yet illuminating race through architectural history. All written, he says, “with absolutely none of that archibabble.”

“The selection was key, which is why these rules emerge,” Pearman says of a series of undeclared editorial rules which informed his selection, three of which are: “Only one building per named architect, only five examples of each type, and it must still exist.” Before these rules were imposed, it could have grown into a much larger beast: “Originally it was going to be twice as big – eleven types could have been thirty, or I could have had ten case studies for each, not five. But it would have taken me another five years… so I'm quite glad.”

These rules prevent the book turning into predictable repeat of the white male canon of architects from all textbooks and one which offers a delightful array of studied and celebrated projects alongside the unexpected. Langham Place Shopping Mall, for example, is a 2004 “nondescript, 15-storeys building” in Mong Kok, Hong Kong, designed by Jon Jerde. It is an architecture, however, that speaks to the modern world of consumerism, but while not iconic or aesthetically remarkable, to Pearman is fascinating through it’s context and symbolism. “Mong Kok is a quite astonishing place – it was the inspiration for Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, a seething commercial centre out of which this tower erupts, surrounded by tiny alleyways.” For similar reasons, but with an entirely different aesthetic, Chetwoods-designed Magna Park, a series of vast Amazon distribution warehouses in the Milton Keynes countryside.

fig.i - About Buildings spread featuring Langham Shopping Mall. fig.ii - Magna Park

That such projects are present illustrates that About Buildings is not designed to be a list of iconic starchitect-designed showpieces: “I am avoiding a lot of the showy stuff. I'm avoiding Bjarke Ingels and so on, it can tend to dominate, and I'm quite fond of good, ordinary, more pragmatic buildings – I think that landmarks can look after themselves!” That said, the obvious big names do make an appearance: “There had to be a Mies van der Rohe, a Frank Lloyd Wright and a Le Corbusier.”

“I wrote about 10% more buildings that were included,” Pearman says, adding that with the rules of one-building-per-designer they had to get culled. Mies’s Seagram Building in New York, for example, made way for his Villa Tugendhat in Czechia. There were many from Le Corbusier to choose from, but Pearman plumped for Notre Dame du Haut, his chapel at Ronchamp. “It completely blew me away – it was an obvious example to have,” Pearman says, though he has not been to every building in the book: “These days our lives have been transformed by Google Earth and Street View, they’re just so incredibly useful to get an idea of the surroundings – it’s not the same as going to see a building but often, and certainly with cultural buildings, people have photographed the inside.”

fig.iii - About Buildings spread featuring Johnson Wax Headquarters. fig.iv - Villa Tugendhat

The two themed chapters on Museums and Performance will interest readers of recessed.space. Here, Pearman compresses the history of cultural architecture into five case studies – though in chapter introductions he always manages to squeeze in a few other references to broaden the discussion, such as a discussion of Andrea Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico in the Performance chapter. “For instance,” he adds, “I thought how can I not have Lina Bo Bardi, so she's the intro to culture building section but she's not one of the case studies – I was trying to cheat by trying to get lots more buildings into the intros.”

The Bo Bardi building mentioned is her São Paulo Museum of Modern Art, included in the introduction to the Museums section in an introductory text which starts with Elias Ashmole, who in 1683 transferred 26 wooden chests containing is eclectic collection of worldly objects from London to Oxford. Once unpacked, they formed the basis of the world’s first purpose-built museum, the Ashmolean.

“It all comes down to stuff in boxes. Obviously, the British Museum is a prime example because it also started from the personal collection of Hans Sloane – I think that we need nerds to collect stuff don't we? If you go to any museum it seems like it’s all nerds specialising in some sort of thing just getting their boxes together.”

fig.v - About Buildings spread featuring São Paulo Museum of Modern Art. fig.vi - Moulin Saulnier Cocoa Mill

Now, however, the boxes are grander and larger than ever before. Museums and cultural buildings now are perhaps more akin to the Amazon warehouses than any other type of place in the book. In a way, Pearman says, this is at the root of the book from synopsis stage, wondering “why do buildings look different from each other? Not because of style, or because of geography, but just because of their uses. Why does a theatre look different to a factory?” He continues with an example, “In fact, the big museums now are actually factories, look at all the set design taking place in the Royal Opera House for example, they've got conveyor belts and machinery.”

Manchester’s Aviva Studios (see 00147) by OMA – who do make an entry with the CCTV building in Beijing – was finished too late for inclusion in About Buildings, but it speaks to Pearman’s interests. “I went to it and thought that it was very meta – we used to do culture in found industrial spaces, so they made a new building which looks like a found industrial space. I can understand the logic of that actually, although it’s a masterwork of value engineering! But you'd never have this in London, there's some kind of Manchester-ey thing going on.”

The five selected museums are the Uffizi (1583) by Giorgio Vasari and Bernardo Buontalenti, John Soane’s Dulwich Picture Gallery (1814), the Pompidou Centre (1977) by Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, and Gianfranco Franchini, Ningbo History Museum (2008) by Amateur Architecture Studio, and David Adjaye’s Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (2016).

fig.vii - About Buildings spread featuring the Pompidou Centre. fig.viii - Tugendhat Villa

There are, you can see, many omissions enforced by the editorial rules. No Zaha Hadid, for example, who perhaps fell into the “showy stuff” category, but Pearman nearly included MAXXI Museum in Rome: “I'm more forgiving of MAXXI, because I think it was the last Zaha building that was pretty much hand drawn, as opposed to using Patrik Schumacher’s computers.”

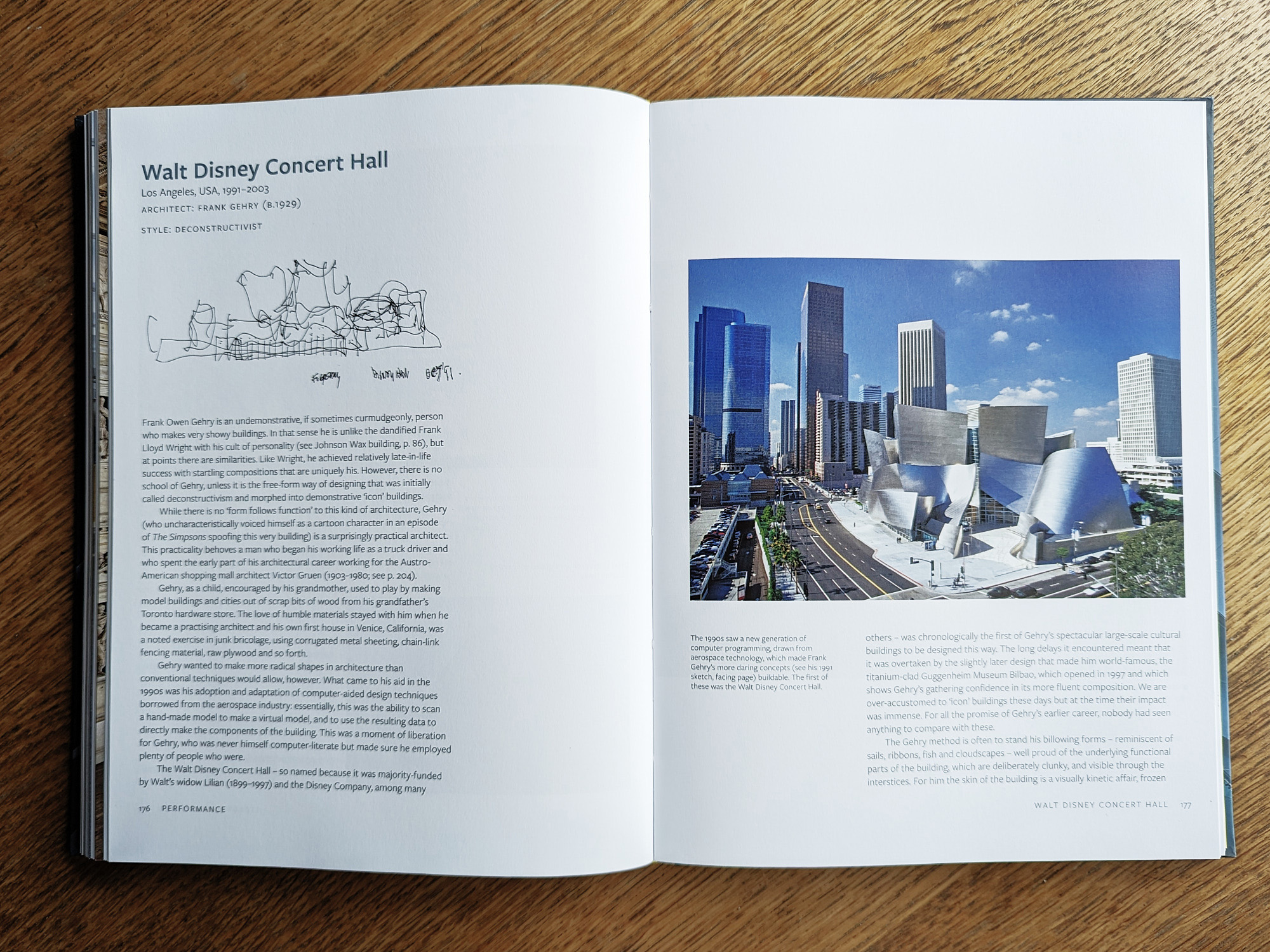

Another starchitect, Frank Gehry, did make the cut with the Performance section including leading up to his LA Walt Disney Concert Hall (2003), having already toured through: the Theatre at Epidauros (4th century BCE) by Polykleitos the Younger; the 1997 rebuild of Richard Burbage’s 1614 Globe Theatre by Theo Crosby, Peter Street, and John Orrell; the Bayreuth Festspielhaus (1876) by Richard Wagner, Gottfried Semper, Otto Brückwald, and Carl Brandt; and the Sydney Opera House (1973) by Jørn Utzon.

“I featured it rather than the Guggenheim Bilbao,” Pearman explains, “which is another obviously missing one from the book. Because it is one building per architect, I thought I'd go for Walt Disney because although it was a little later than the Guggenheim but was designed before it.” Gehry is clearly an architect who can be included in the “showy stuff” category, and also divides opinions like few others. “I do get disarmed by Gehry. I know I shouldn't, but I do go wanting to hate a building and then I end up thinking, ‘oh Frank, you old rascal, you!’” Pearman says, adding “the one I visited expecting to hate and came away going, ‘oh, you've done it again,’ was the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Bois de Boulogna, Paris. There's all the usual acres of leftover space and it's really crude because Gehry doesn’t do fine details – and I rather loved it!”

fig.ix - About Buildings spread featuring Walt Disney Concert Hall. fig.x - Galleria Vittorio Emmanuele II

Across the 55 places eloquently described and discussed in About Buildings, there will be many which similarly divide the reader. Across all periods and typologies there will be designs and ideas which disgust as well as delight, but this is not a coffee table book of aesthetic titillation, despite a rich selection of images throughout. About Buildings is a guidebook across the globe and into the past, taking the reader not only into buildings they may never visit in the flesh, but into the stories and meaning behind them also. Pearman is an excellent guide.

fig.xi - About Buildings cover

Hugh Pearman is a writer, architecture critic, editor, and Chairman

of the Twentieth Century Society. Previously architecture and design critic of

The Sunday Times and editor of the RIBA Journal, he also contributes to many

other media including RA Magazine, Architectural Record, and the BBC.

buy

About Buildings is available direct from the Yale University Press website, or from most bookshops. More information available at:

www.yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300263442/about-architecture

images

fig.i,iii,v,vii,ix,xi About Buildings, by Hugh Pearman, published by Yale University Press. Photo

© Carlo Zambon.

fig.ii

Magna

Park, Milton Keynes, UK, 1987–2020, Chetwoods. Image courtesy of GLP / Sky

Revolutions

figs.iv,viii

Villa Tugendhat,

Brno, Czechia, 1928–30, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with designer Lilly Reich. ©

photos David Zidlicky.

fig.vi

Moulin Saulnier Cocoa

Mill, Noisiel, France, 1869–72, Jules Saulnier and Armand Moisant. Cellen

Wikipedia.

fig.x

Galleria Vittorio

Emmanuele II, Milan, Italy, 1861–78, Giuseppe Mengoni. Foto Andrea Scuratti /

Comune di Milano

publication date

15 December 2023

tags

David Adjaye, Amateur Architecture Studio, Elias Ashmole, The Ashmolean, Aviva Studios, Bayreuth Festspielhaus, Bladerunner, Lina Bo Bardi, Book, Carl Brandt, The British Museum, Otto Brückwald, Richard Burbage, Bernardo Buontalenti, CCTV, Chetwoods, Theo Crosby, Dulwich Picture Gallery, Gianfranco Franchini, Frank Gehry, The Globe Theatre, The Guggenheim Bilbao, Zaha Hadid, History, Bjarke Ingels, Jon Jerder, Langham Place Shopping Mall, Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, The Louis Vuitton foundation, MAXXI, Ningbo History Museum, OMA, John Orrell, Magna Park, Andrea Palladio, Hugh Pearman, Renzo Piano, Polykleitos the Younger, The Pompidou Centre, Richard Rogers, The Royal Opera House, São Paulo Museum of Modern Art, Gottfried Semper, Hans Sloane, The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, John Soane, Peter Street, The Sydney Opera House, Teatro Olimpico, The Theatre at Epidauros, The Uffizi, Jørn Utzon, Mies van der Rohe, Giorgio Vasari, Villa Tugendhat, Richard Wagner, Walt Disney Concert Hall, Yale University Press

www.yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300263442/about-architecture