Exploring the soft city of Saul Leiter

At MK Gallery, the work of photographer Saul Leiter is eplored in an exhibition that transports the visitor from the British new town of Milton Keynes into the streets of New York. With an eye that deeply reads the nuances & textures of the city, the images have a softness & shyness that give the hard urban edge a more gentle form, as Will Jennings writes.

Saul Leiter might perhaps not be as recognised in the canon of

20th century street photographers as names such as the likes of

William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, Garry Winogrand, or William Klein, but a new

exhibition at MK Gallery in Milton Keynes sets out to ensure his name is firmly

remembered alongside his contemporaries. His photographs are soft, and he used

his camera within America’s modernising streets in an almost shy manner, and

was equally as reserved and quietly spoken in person when discussing his

practice and legacy.

This sense of distance and calm – as opposed, for example, to the busyness of Shore, proximity of Winogrand, or colour play of Eggleston – might be a reason why his name has not been quite as widely known, but Anne Morin’s curation – co-produced by the Rencontres d'Arles and DiChromaPhotography, Madrid, with the collaboration of the Saul Leiter Foundation, New York – makes a strong contribution to increasing recognition.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Leiter had been expected to become a Rabbi, and had begun the theological education that at least 27 males in his family had undertaken previously before he decided to pursue his dream of becoming a painter. While establishing his painterly practice, he began to develop an interest in the camera, emerging into a circle of photographers including Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, and Robert Frank. Drawing inspiration from a range of historic and cultural sources, much of his work was concerned with looking at the city streets, particularly those of the East Village neighbourhood, home to the apartment he lived in for sixty years and which is now his foundation.

He went on to work across fashion, with shoots in magazines including Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Elle from the 1950s to 1980s, though while continuing this commercial work he continued to document the city, its people, and every small moment his eye caught, building up an archive of 15,000 black and white prints, 40,000 colour slides and nearly as many black and white negatives. He was prolific, but the scale of the archive is daunting, and it’s only since his death in 2013 that the richness of this work has been discovered and presented across publications and exhibitions.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.iv-vii

Through Leiter’s lens, the city is the main protagonist. There are people present, often centre to the frame where the eye may be expected to focus, but instead Leiter’s compositions force the viewer to dart around the image, seemingly looking at everything except the central figure. Often, his images are captured through a narrow opening of part of the city, reducing the city to a tight, voyeuristic glimpse. Sometimes his focus falls on the window between him and the street, capturing the architectural surface and marks upon it, relegating the figures walking by to out of focus background. On a sunny day, the shade may cast over the face of the person who may be expected to be the main character of the image, and instead the everyday signage, awnings, vehicles, and fractured hubbub of the city becomes the main feature. The focus may fall short of what may be expected to be the feature component, and obliquely pick up an inconsequential puddle, paving, or other urban mundanity.

While these areas of focus may be mundane, they are not uninteresting. They enable the images to work as rich studies of place, as time capsules from the everyday hum of modern Manhattan, and in such a democratic flattening of place, people simply become another part of the city, interesting but not more interesting than the rich palette Leiter’s eye catches. This is not to say he is oblivious to people, they are nearly always present, but anonymous.

![]()

![]()

There are 171 photographs across the series of 6a architects-designed MK Gallery gallery spaces, and amongst the selection themes begin to emerge: the frequency of lamp posts cutting across faces, umbrellas, windows, hats, reflections, rain, and a recurring top-down vantage. Leiter’s own apartment, on East 10th Street, was 30 metres above the city’s elevated trainline, and for three years before the line closed Leiter frequently made images looking down onto the platform from the heights of the city. But his gaze just as frequently poked through gaps in the city surfaces, through a vehicle window, or towards a forgotten urban corner.

The images, which are hung in a very traditional singular line throughout the enfilade of galleries without really trying to make use of the generous height and sense of space, are supplemented by selected quotes extracted from writings and interviews of the artist. In places they are cute, but rarely offer any deep insight into his drive or help the visitor deepen their experience of the images. Similarly, there are a couple of vitrines showing published fashion work alongside contact sheets, as well as some personal paraphernalia, and a final room features a video of an interview with the artist, but there is little in the curation or mode of display which supports the poetry, play, or intrigue of his images – the images themselves are rich, deep, and alluring but feel a little dragged back by a rather cold and monotonous presentation on grey walls.

![]()

![]()

Photographs are not always the easiest medium to show by themselves (though the William Klein + Daido Moriyama exhibition at Tate Modern in 2012 did very well at showing how such rich street photography could own a gallery space, rather than be subsumed by it) and here there is the addition of select Saul Leiter paintings to break the rhythm of framed prints. His paintings are interesting considering it was his starting-out artform, and that it was something he worked at alongside his photography throughout his life, though a medium he was far less well known for. The archive he left behind includes some 4,000 paintings, some on large canvases but often on found cardboard or spread-out papers.

There could potentially be a rich exhibition pairing his painting and photographs, but with this curation there are too few paintings to really read in any motifs or ongoing relationships across his ways of making, and with very little contextual writing or framing to help the reader draw their own conclusions. Certainly, the paintings and photographs are hung in proximity enough to offer curious and pleasant aesthetic relationships, but without any of the depth that the curation shows of Leiter’s reading of the city.

None of this, however, detracts from individual moments within many of the selected images and the imagined stories the reader is invited to concoct across and between them. A triptych of unrelated images – red stairs, a worker painting a large W from a city sign, and a portrait of a man in a cap and tattered work clothes – reads as if a city symphony storyboard or frames from a multitude of possible dramas and city events which go on day after day after day. They only make the viewer wonder what other stories and readings of the city exist between the other 100,000 images in his archive.

![]()

This sense of distance and calm – as opposed, for example, to the busyness of Shore, proximity of Winogrand, or colour play of Eggleston – might be a reason why his name has not been quite as widely known, but Anne Morin’s curation – co-produced by the Rencontres d'Arles and DiChromaPhotography, Madrid, with the collaboration of the Saul Leiter Foundation, New York – makes a strong contribution to increasing recognition.

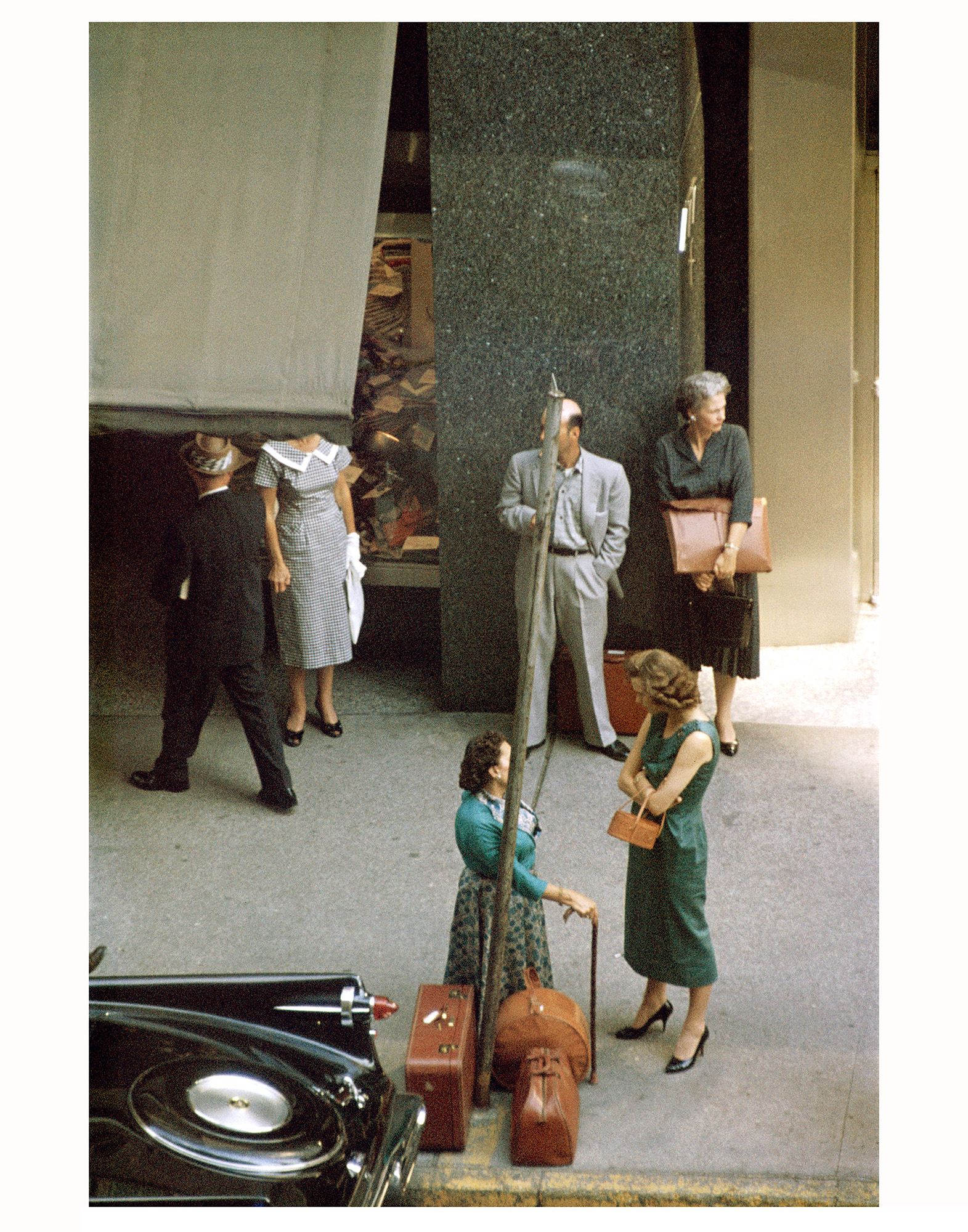

figs.i-iii

Leiter had been expected to become a Rabbi, and had begun the theological education that at least 27 males in his family had undertaken previously before he decided to pursue his dream of becoming a painter. While establishing his painterly practice, he began to develop an interest in the camera, emerging into a circle of photographers including Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, and Robert Frank. Drawing inspiration from a range of historic and cultural sources, much of his work was concerned with looking at the city streets, particularly those of the East Village neighbourhood, home to the apartment he lived in for sixty years and which is now his foundation.

He went on to work across fashion, with shoots in magazines including Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Elle from the 1950s to 1980s, though while continuing this commercial work he continued to document the city, its people, and every small moment his eye caught, building up an archive of 15,000 black and white prints, 40,000 colour slides and nearly as many black and white negatives. He was prolific, but the scale of the archive is daunting, and it’s only since his death in 2013 that the richness of this work has been discovered and presented across publications and exhibitions.

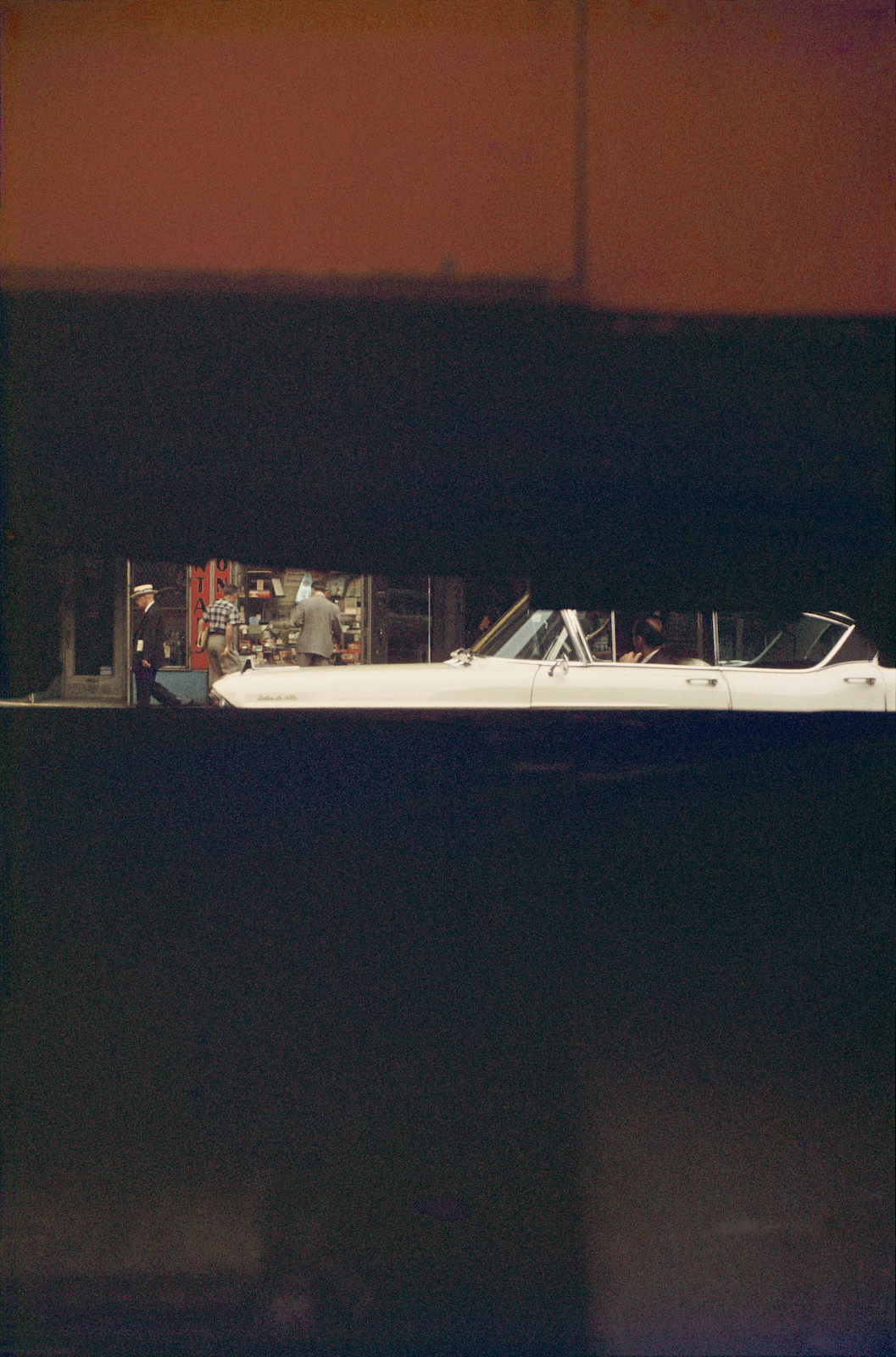

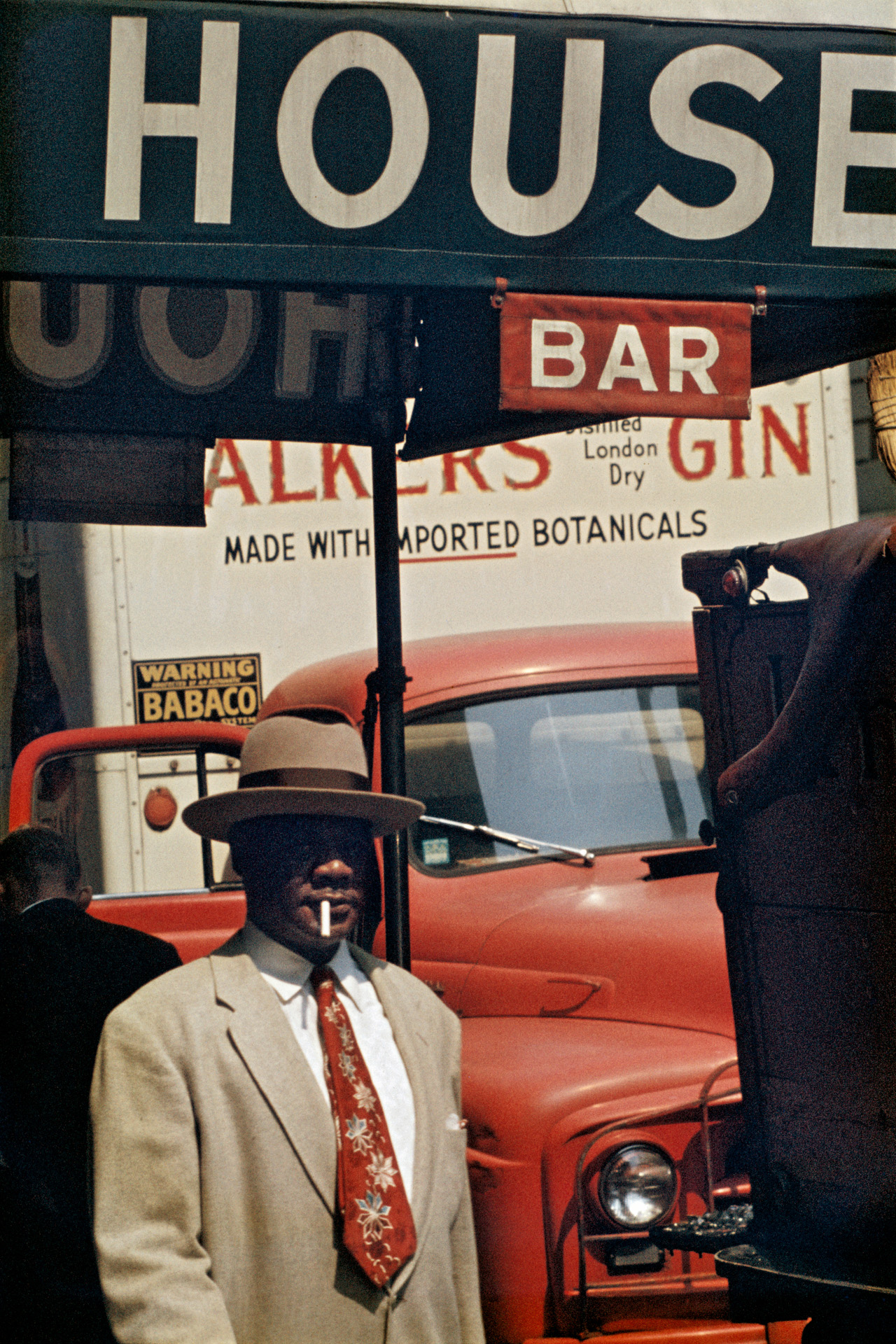

figs.iv-vii

Through Leiter’s lens, the city is the main protagonist. There are people present, often centre to the frame where the eye may be expected to focus, but instead Leiter’s compositions force the viewer to dart around the image, seemingly looking at everything except the central figure. Often, his images are captured through a narrow opening of part of the city, reducing the city to a tight, voyeuristic glimpse. Sometimes his focus falls on the window between him and the street, capturing the architectural surface and marks upon it, relegating the figures walking by to out of focus background. On a sunny day, the shade may cast over the face of the person who may be expected to be the main character of the image, and instead the everyday signage, awnings, vehicles, and fractured hubbub of the city becomes the main feature. The focus may fall short of what may be expected to be the feature component, and obliquely pick up an inconsequential puddle, paving, or other urban mundanity.

While these areas of focus may be mundane, they are not uninteresting. They enable the images to work as rich studies of place, as time capsules from the everyday hum of modern Manhattan, and in such a democratic flattening of place, people simply become another part of the city, interesting but not more interesting than the rich palette Leiter’s eye catches. This is not to say he is oblivious to people, they are nearly always present, but anonymous.

figs.viii,ix

There are 171 photographs across the series of 6a architects-designed MK Gallery gallery spaces, and amongst the selection themes begin to emerge: the frequency of lamp posts cutting across faces, umbrellas, windows, hats, reflections, rain, and a recurring top-down vantage. Leiter’s own apartment, on East 10th Street, was 30 metres above the city’s elevated trainline, and for three years before the line closed Leiter frequently made images looking down onto the platform from the heights of the city. But his gaze just as frequently poked through gaps in the city surfaces, through a vehicle window, or towards a forgotten urban corner.

The images, which are hung in a very traditional singular line throughout the enfilade of galleries without really trying to make use of the generous height and sense of space, are supplemented by selected quotes extracted from writings and interviews of the artist. In places they are cute, but rarely offer any deep insight into his drive or help the visitor deepen their experience of the images. Similarly, there are a couple of vitrines showing published fashion work alongside contact sheets, as well as some personal paraphernalia, and a final room features a video of an interview with the artist, but there is little in the curation or mode of display which supports the poetry, play, or intrigue of his images – the images themselves are rich, deep, and alluring but feel a little dragged back by a rather cold and monotonous presentation on grey walls.

figs.x,xi

Photographs are not always the easiest medium to show by themselves (though the William Klein + Daido Moriyama exhibition at Tate Modern in 2012 did very well at showing how such rich street photography could own a gallery space, rather than be subsumed by it) and here there is the addition of select Saul Leiter paintings to break the rhythm of framed prints. His paintings are interesting considering it was his starting-out artform, and that it was something he worked at alongside his photography throughout his life, though a medium he was far less well known for. The archive he left behind includes some 4,000 paintings, some on large canvases but often on found cardboard or spread-out papers.

There could potentially be a rich exhibition pairing his painting and photographs, but with this curation there are too few paintings to really read in any motifs or ongoing relationships across his ways of making, and with very little contextual writing or framing to help the reader draw their own conclusions. Certainly, the paintings and photographs are hung in proximity enough to offer curious and pleasant aesthetic relationships, but without any of the depth that the curation shows of Leiter’s reading of the city.

None of this, however, detracts from individual moments within many of the selected images and the imagined stories the reader is invited to concoct across and between them. A triptych of unrelated images – red stairs, a worker painting a large W from a city sign, and a portrait of a man in a cap and tattered work clothes – reads as if a city symphony storyboard or frames from a multitude of possible dramas and city events which go on day after day after day. They only make the viewer wonder what other stories and readings of the city exist between the other 100,000 images in his archive.

fig.xii

Saul Leiter (American, 1923–2013) was a photographer & painter whose work was an integral part of the creation of the New York School. Growing up in Pittsburgh, PA, Leiter studied to become a rabbi. When he was 23 years old, he exchanged school for New York City and a career as an artist. In his early years, Leiter was encouraged by Pousette-Dart & W. Eugene Smith to try his hand at photography, venturing into color photography in 1948. In 1953, Leiter's black-and-white photographs were included in an exhibition of Edward Steichen’s entitled Always the Young Stranger at The Museum of Modern Art. Leiter's color fashion photographs were published by Henry Wolfe in Esquire and Harper's Bazaar in the late 1950s with a 20-year fashion photography career leading to publications in such magazines as British Vogue, Elle, Nova, Show & Queen.

In 2008, Leiter had six solo exhibitions spanning the globe, including shows in Paris, Milan, New York & London. His work is known worldwide. Leiter's first museum exhibition in Europe was hosted by the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris.

www.saulleiterfoundation.org

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.willjennings.info

visit

Saul Leiter: An Unfinished World is on at MK Gallery until 2

June.

Further details available at: https://mkgallery.org/event/saul-leiter/

images

fig.i Saul Leiter, Untitled, undated.

© Saul Leiter Foundation

fig.iii Saul Leiter, Footprints, c. 1950.

© Saul Leiter Foundation

fig.iv Saul Leiter, Pull, c. 1960.

© Saul Leiter Foundation

fig.v Saul Leiter, Untitled, undated.

© Saul Leiter Foundation

fig.vi Saul Leiter, Through Boards, 1957.

© Saul Leiter Foundation. Courtesy Florence and Damien

fig.vi Saul Leiter, Harlem, 1960.

© Saul Leiter Foundation

figs.ii,viii-xii Saul Leiter: An Unfinished World, at MK Gallery. Installation photographs

© Rob Harris

publication date

26 February 2024

tags

6a architects, Archive, Black and white, City, East Village, Fashion, Fashion photography, Will Jennings, Saul Leiter, Manhattan, MK Gallery, New York, Anne Morin, Painting, Photography, Street photography, Urban

Further details available at: https://mkgallery.org/event/saul-leiter/