A night-time flâneuse of the nonplace: Tales of

Estrangement by Effie Paleologou

In her book Tales of Estrangement, photographer artist Effie Paleologou leads us on an uncanny & unnerving journey through an anonymous, desolate urbanity. A compression of Athens & London, the Mack Books-published project is a psychological exploration of the shadows.

There is no introductory text to Effie Paleologou’s book Tales

of Estrangement. It opens with an image of the back of a road sign and we

could be anywhere. We know it’s the night, the only light coming from yellow

streetlight reflecting from the metal signage and distant, hazy clouds, but we

have been deposited into a nonplace, an anywhereplace, or perhaps an

everywhereplace. That we can only see the back of the signage is a warning that

we will not be given directions on the journey we about to undertake.

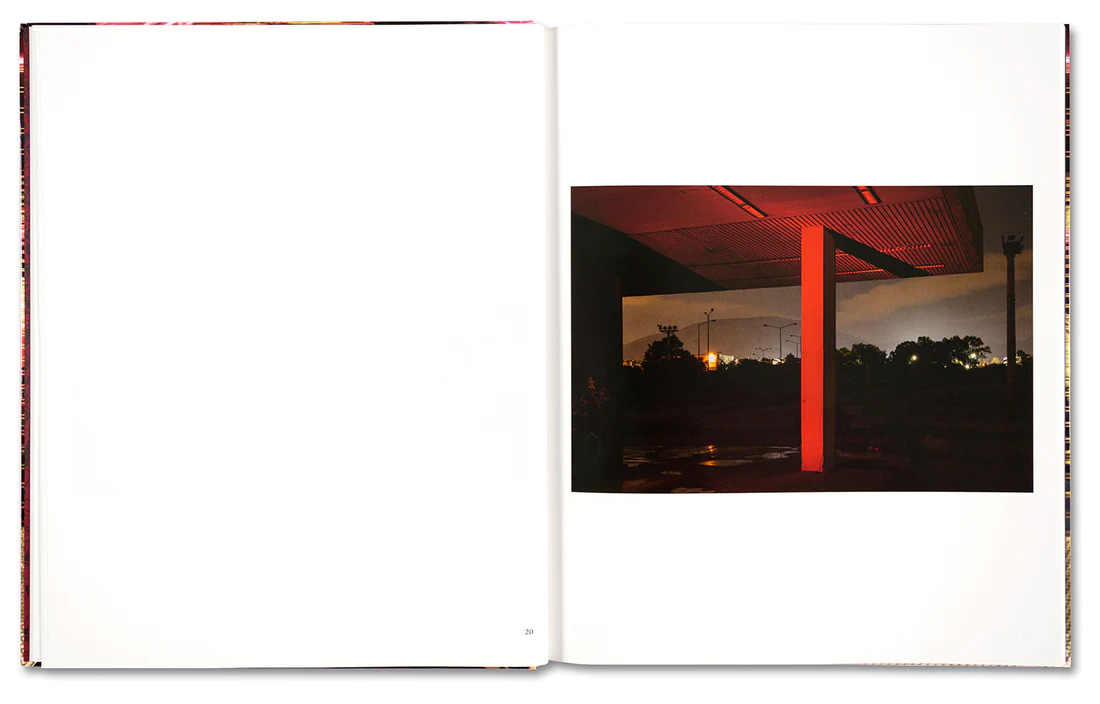

The images continue, snapshots of what seems to be a solitary walk through a place that refuses to reveal itself. Artificial lighting, from civic infrastructure and through windows, implies there is life somewhere, but a scene of an empty pram by itself in a snow-covered empty public space suggests otherwise.

![]()

![]()

It is haunting, and every glimpse of the camera – whether directly across open space, or more often trying to find evidence of presence within reflections, open windows, and fleeting moments of city detail – only serve to deepen the sense of loneliness and otherness. The photographs constantly remind us we are deep within urbanity, but don’t help us know where. An image looking down onto a motorway, presumably from a pedestrian bridge, reveals the road as empty and silent. A photograph gazing towards what seems to be a small doorway into a multistorey carpark, a bright light glowing from within, suggests signs of life, but none comes.

The images in Paleologou’s series combine to create an eerie, unnerving night-time walk around a city, the photographs acting as furtive glances towards corners, crevices, and spaces where a sense of life might be found, but the longer the search goes on, the sense of abandonment and absence grows stronger. There is an image of a towerblock’s concrete and gridded rebar shell, lights inside giving it an air of hauntedness. This is surely a building site, you think, but has it – like everything seems to in this book – stopped?

![]()

![]()

Time is strange on this journey. The building site seems to suggest a city paused, where we viewers have somehow glitched our way into an existence where all other life has momentarily withdrawn. But other images are lit by the slow-exposure drag of vehicle lights across the frame, but though we are left unsure as to whether we the viewer are standing still as a car drives past, or if it’s some kind of pre-glitch ghostly afterimage lingering in the atmosphere, movement fixed in air.

Another image captures a glass-fronted office built into a container, the interior clearly in a state of abandonment and disrepair: the pinboard is empty, the desktop fan motionless, there are cracks in the glazing – was someone trying to get in, or get out? It’s bright inside, almost as if, like the Mary Celeste, it was discovered by Paleologou floating in a sea of darkness, its inhabitants long gone. Perhaps this the site office for the abandoned building site? The images do seem to show the city as construction site, or perhaps deconstruction site. A Potemkin city within which we are searching for a way out.

![]()

![]()

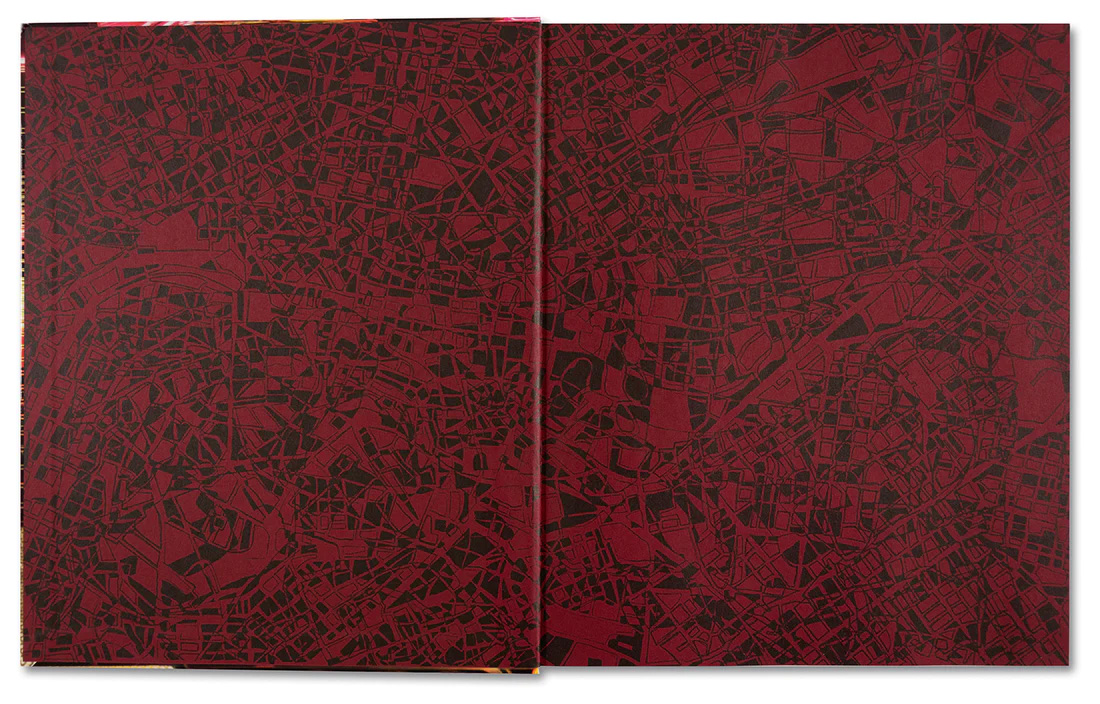

There are, after 47 photographs which act to dislocate and compound a sense of both loss and being lost, two texts which may be the key to revealing something of the journey just undertaken. The first is by Iain Sinclair, no stranger to walking cities and searching for meaning within discovered fragments, and a second from Brian Dillon titled Everything Merges With The Night. We learn from Sinclair that the photographs are a mix of London and Athens, compressing the two together into an alliance of unnamed urbanity. Fantasy novels often lead with a map of the territory to aid the reader understand the geography of the unfolding drama, and in Tales of Estrangement there is something similar. With this new knowledge of London and Athens we might revisit the book’s endpapers, which had initially perhaps been read as an abstract pattern but now can be seen as conflated noll maps of the two capital cities, but it only serves to further disorientate our physical and psychological predicament.

In his text, Dillon tells us of the artist’s interest in the flâneur, that imaginary character forged by Edgar Allen Poe, developed by Charles Beaudelaire as The Man of the Crowd, and then revisited by Walter Benjamin, much-loved by architects and artists alike. In 2016 the flâneur again evolved, this time through writer Lauren Elkin in her book Flâneuse. The feminine title of her book she says is “an imaginary definition” not included in most French dictionaries, a slang word created in the 1840s but never achieved the usage or romance of the male flaneur, nearly all historic literature of urban walkers – as with art, culture, politics, and society – is male led.

![]()

![]()

The city Paleologou has forged within the pages of Tales of Estrangement speak more to this feminine gaze than the men of the city written about before. This is not to say that a woman’s existence in the city is one of constant fear or threat, but the images speak to an awareness of the shadows, a constant eye on what might be around the corner, a reading of place that many of us – especially men – simply don’t need to read into our urban realm to the same level.

Tales of Estrangement was published in 2022, in the shadow of Covid lockdowns, and carries a memorial aura of how the pandemic turned busy, familiar urban spaces into uncanny, strange, and cold voids. A time saturated with loss, one senses that the estrangement within Effie Paleologou’s series of images is not one of separation from other people, so much as from the very city itself.

![]()

The images continue, snapshots of what seems to be a solitary walk through a place that refuses to reveal itself. Artificial lighting, from civic infrastructure and through windows, implies there is life somewhere, but a scene of an empty pram by itself in a snow-covered empty public space suggests otherwise.

It is haunting, and every glimpse of the camera – whether directly across open space, or more often trying to find evidence of presence within reflections, open windows, and fleeting moments of city detail – only serve to deepen the sense of loneliness and otherness. The photographs constantly remind us we are deep within urbanity, but don’t help us know where. An image looking down onto a motorway, presumably from a pedestrian bridge, reveals the road as empty and silent. A photograph gazing towards what seems to be a small doorway into a multistorey carpark, a bright light glowing from within, suggests signs of life, but none comes.

The images in Paleologou’s series combine to create an eerie, unnerving night-time walk around a city, the photographs acting as furtive glances towards corners, crevices, and spaces where a sense of life might be found, but the longer the search goes on, the sense of abandonment and absence grows stronger. There is an image of a towerblock’s concrete and gridded rebar shell, lights inside giving it an air of hauntedness. This is surely a building site, you think, but has it – like everything seems to in this book – stopped?

Time is strange on this journey. The building site seems to suggest a city paused, where we viewers have somehow glitched our way into an existence where all other life has momentarily withdrawn. But other images are lit by the slow-exposure drag of vehicle lights across the frame, but though we are left unsure as to whether we the viewer are standing still as a car drives past, or if it’s some kind of pre-glitch ghostly afterimage lingering in the atmosphere, movement fixed in air.

Another image captures a glass-fronted office built into a container, the interior clearly in a state of abandonment and disrepair: the pinboard is empty, the desktop fan motionless, there are cracks in the glazing – was someone trying to get in, or get out? It’s bright inside, almost as if, like the Mary Celeste, it was discovered by Paleologou floating in a sea of darkness, its inhabitants long gone. Perhaps this the site office for the abandoned building site? The images do seem to show the city as construction site, or perhaps deconstruction site. A Potemkin city within which we are searching for a way out.

There are, after 47 photographs which act to dislocate and compound a sense of both loss and being lost, two texts which may be the key to revealing something of the journey just undertaken. The first is by Iain Sinclair, no stranger to walking cities and searching for meaning within discovered fragments, and a second from Brian Dillon titled Everything Merges With The Night. We learn from Sinclair that the photographs are a mix of London and Athens, compressing the two together into an alliance of unnamed urbanity. Fantasy novels often lead with a map of the territory to aid the reader understand the geography of the unfolding drama, and in Tales of Estrangement there is something similar. With this new knowledge of London and Athens we might revisit the book’s endpapers, which had initially perhaps been read as an abstract pattern but now can be seen as conflated noll maps of the two capital cities, but it only serves to further disorientate our physical and psychological predicament.

In his text, Dillon tells us of the artist’s interest in the flâneur, that imaginary character forged by Edgar Allen Poe, developed by Charles Beaudelaire as The Man of the Crowd, and then revisited by Walter Benjamin, much-loved by architects and artists alike. In 2016 the flâneur again evolved, this time through writer Lauren Elkin in her book Flâneuse. The feminine title of her book she says is “an imaginary definition” not included in most French dictionaries, a slang word created in the 1840s but never achieved the usage or romance of the male flaneur, nearly all historic literature of urban walkers – as with art, culture, politics, and society – is male led.

The city Paleologou has forged within the pages of Tales of Estrangement speak more to this feminine gaze than the men of the city written about before. This is not to say that a woman’s existence in the city is one of constant fear or threat, but the images speak to an awareness of the shadows, a constant eye on what might be around the corner, a reading of place that many of us – especially men – simply don’t need to read into our urban realm to the same level.

Tales of Estrangement was published in 2022, in the shadow of Covid lockdowns, and carries a memorial aura of how the pandemic turned busy, familiar urban spaces into uncanny, strange, and cold voids. A time saturated with loss, one senses that the estrangement within Effie Paleologou’s series of images is not one of separation from other people, so much as from the very city itself.

Effie Paleologou is a London-based visual artist whose work has been exhibited internationally & is held in collections such as the Victoria & Albert Museum in London & the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens.

buy

Tales of Estrangement is published by Mack Books and available from their website:

www.mackbooks.co.uk/products/tales-of-estrangement-br-effie-paleologou

images

All images from Tales of Estrangement by Effie Paleologou, courtesy of the artist & Mack books.

publication date

28 February 2024

tags

Absence, Athens, Covid, Darkness, Brian Dillon, Lauren Elkin, Flâneur, Flâneuse, Light, London, Mack Books, Night, Night-time, Effie Paleologou, Photography, Shadows, Iain Sinclair, Walking, Windows

www.mackbooks.co.uk/products/tales-of-estrangement-br-effie-paleologou