Venice 2024: Robert Zhao Renhui’s study of a Singaporean

secondary forest

For the Singapore pavilion at Venice Biennale of Art 2024, artist

Robert Zhao Renhui considered a forest from his apartment’s window. Having

regrown from an ancient woodland, destroyed by human occupation over the 20th

century, it offers a space of co-existence, regrowth & analysis of both

past and possible futures.

The edgeland between one thing and another is rich territory

in both architecture and art. Somewhat indeterminate, a space of shifting encounter,

where meaning, form, expectation, and meaning morph from one norm to another,

these are places where exciting things happen – intentionally or otherwise.

For the Singapore Pavilion of the 2024 Venice Biennale or Art, Robert Zhao Renhui has taken his creative lens to such a space, and he didn’t have to travel far. Considering Singapore’s secondary forests – woodlands that have regrown after the original was lost through human destruction or plantation – some of the work within the mixed-media installation was filmed from his apartment window. Singapore is a compressed space of shared existence, emphasised by the fact that the artist’s own domestic space might overlook the penumbra of a secondary forest that is also lived in by a wide variety of animals, who also treat the edgeland as their own.

![]()

![]()

Zhao’s work records the coming together of the various inhabitants of this space between. This could take the form of humans on a walk who suddenly find themselves a little deeper into nature than expected and confronted by a python or a cobra, or it could be a variety of animals – nightjars, herons, tree shrews, otters, fish owls, or crab-eating macaques, for example – leaving the sanctity of the forest and encroaching on the human realm.

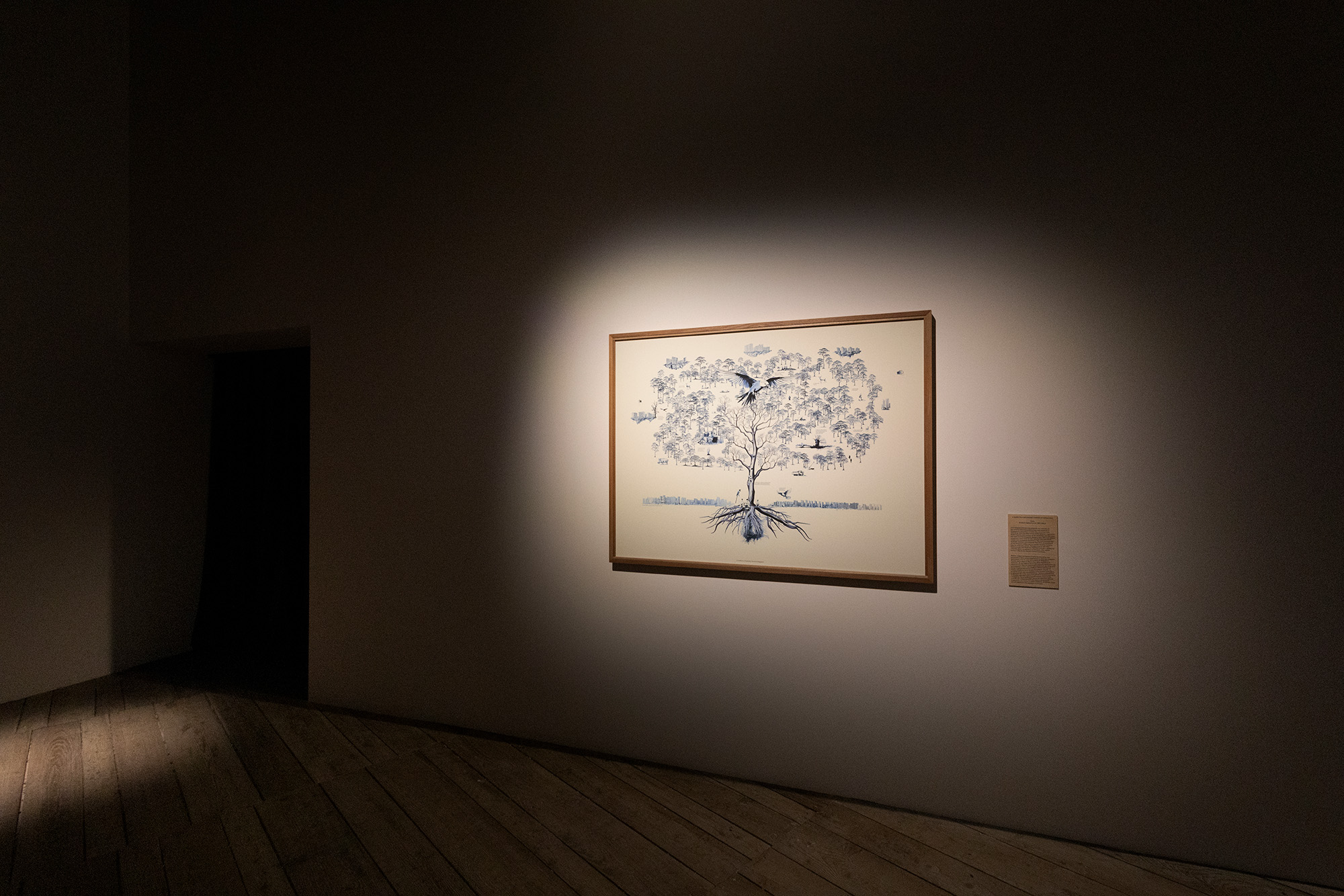

His installation for Biennale, Seeing Forest, comprises a two-screen video work, documentation from his windows – towards the secondary forest and encounters between humans and animals, and how all species coexist in such a space – and a sculptural installation comprising video and found objects enmeshed within a collapsed geometric timber structure. It starts, however, as the visitor enters the main space with a small archival pigment print, A guide to a secondary forest of Singapore (2024).

This drawing of a tree, roots, and distant city, acts as an introductory map to the territory and shared ecology. Short phrases fill the gaps of the drawing: “a trash bin that is also a pond,” “45 deer roam in a field that used to be a hill,” “this was a Colonial British artillery barracks, a plantation, a village.” Central is an oversized parrot launching into flight, with an overlaid phrase, “who knows what the parrot knows.”

![]()

![]()

The two-channel film inside might glimpse into that parrot’s insight. It uses not only footage from Zhao’s apartment window, but also journeys in and through the secondary forest, utilising body temperature and motion-capture cameras to create a slightly othered version of a BBC nature documentary. It captures tents of homeless people, birds washing in a broken concrete drain, a recently considered extinct Sambar deer casually walking through the woods, and boars that leave the sanctity of the trees. A wall text reconsiders these observed moments as quasi spiritual journeys of man and beast through nature, and beyond.

The sculpture offers a compressed imaginary of the secondary forest experience, with foraged objects displayed around the chaotic timber framework, representing a collapsed cabinet of curiosities and all the patriarchal, colonial structures it represents. Inside this mound are various pieces, dutifully listed on a board nearby: “fragments of medicinal bottles issued to the Japanese Imperial Army, 1930s,” “Fragments of ceramics from England and Scotland, most likely belonging to British Soldiers, 1920s-1950s,” “Alcohol bottles discarded by a vagrant living in the forest, laid in neat rows, 1990s,” “A fragment of a rubber cup used for rubber collection, 1900s, “Fallen birds nests found on the road near the hill,” “Fragments of bricks from a British Military Barracks built in 1935, demolished in the late 1960s. The bricks have been worn down by running water from a drain, which used to be a stream.”

![]()

![]()

Enmeshed within are also images of the forest from its use as a rubber plantation, of the deforestation that followed in the 1910s, and of the military occupations that came after. But, this is not completely dystopian as a long list catalogues the various non-human animals that also call this place home, as observed by Zhao from a single 1 squared metre spot: Tiger Shrike, Black-throated Laughing Thrush, Common Sun Skink, Plantain Squirrel, Water Monitor, Reticulated Python, Crab-eating Macaque, Smooth-coated Otter, Brahminy Kite, Pin-striped Tit-Babbler, and many, many more.

Altogether, Zhao’s Seeing Forest is an archive of a place that has never stayed still. Primary shifts in its formation and ecology came from human use and abuse, but within the cracks and with closer analysis the detritus and remains of humanity new societies of nature and animal flourish, despite ongoing deforestation and incursion by man. From his window, Zhao records an occurrence that happens every day at 7pm – parrots flocking to a single tree to roost. And he wonders what they know, and what they may know about the future of the place.

![]()

![]()

For the Singapore Pavilion of the 2024 Venice Biennale or Art, Robert Zhao Renhui has taken his creative lens to such a space, and he didn’t have to travel far. Considering Singapore’s secondary forests – woodlands that have regrown after the original was lost through human destruction or plantation – some of the work within the mixed-media installation was filmed from his apartment window. Singapore is a compressed space of shared existence, emphasised by the fact that the artist’s own domestic space might overlook the penumbra of a secondary forest that is also lived in by a wide variety of animals, who also treat the edgeland as their own.

figs.i,ii

Zhao’s work records the coming together of the various inhabitants of this space between. This could take the form of humans on a walk who suddenly find themselves a little deeper into nature than expected and confronted by a python or a cobra, or it could be a variety of animals – nightjars, herons, tree shrews, otters, fish owls, or crab-eating macaques, for example – leaving the sanctity of the forest and encroaching on the human realm.

His installation for Biennale, Seeing Forest, comprises a two-screen video work, documentation from his windows – towards the secondary forest and encounters between humans and animals, and how all species coexist in such a space – and a sculptural installation comprising video and found objects enmeshed within a collapsed geometric timber structure. It starts, however, as the visitor enters the main space with a small archival pigment print, A guide to a secondary forest of Singapore (2024).

This drawing of a tree, roots, and distant city, acts as an introductory map to the territory and shared ecology. Short phrases fill the gaps of the drawing: “a trash bin that is also a pond,” “45 deer roam in a field that used to be a hill,” “this was a Colonial British artillery barracks, a plantation, a village.” Central is an oversized parrot launching into flight, with an overlaid phrase, “who knows what the parrot knows.”

figs.iii,iv

The two-channel film inside might glimpse into that parrot’s insight. It uses not only footage from Zhao’s apartment window, but also journeys in and through the secondary forest, utilising body temperature and motion-capture cameras to create a slightly othered version of a BBC nature documentary. It captures tents of homeless people, birds washing in a broken concrete drain, a recently considered extinct Sambar deer casually walking through the woods, and boars that leave the sanctity of the trees. A wall text reconsiders these observed moments as quasi spiritual journeys of man and beast through nature, and beyond.

The sculpture offers a compressed imaginary of the secondary forest experience, with foraged objects displayed around the chaotic timber framework, representing a collapsed cabinet of curiosities and all the patriarchal, colonial structures it represents. Inside this mound are various pieces, dutifully listed on a board nearby: “fragments of medicinal bottles issued to the Japanese Imperial Army, 1930s,” “Fragments of ceramics from England and Scotland, most likely belonging to British Soldiers, 1920s-1950s,” “Alcohol bottles discarded by a vagrant living in the forest, laid in neat rows, 1990s,” “A fragment of a rubber cup used for rubber collection, 1900s, “Fallen birds nests found on the road near the hill,” “Fragments of bricks from a British Military Barracks built in 1935, demolished in the late 1960s. The bricks have been worn down by running water from a drain, which used to be a stream.”

figs.v,vi

Enmeshed within are also images of the forest from its use as a rubber plantation, of the deforestation that followed in the 1910s, and of the military occupations that came after. But, this is not completely dystopian as a long list catalogues the various non-human animals that also call this place home, as observed by Zhao from a single 1 squared metre spot: Tiger Shrike, Black-throated Laughing Thrush, Common Sun Skink, Plantain Squirrel, Water Monitor, Reticulated Python, Crab-eating Macaque, Smooth-coated Otter, Brahminy Kite, Pin-striped Tit-Babbler, and many, many more.

Altogether, Zhao’s Seeing Forest is an archive of a place that has never stayed still. Primary shifts in its formation and ecology came from human use and abuse, but within the cracks and with closer analysis the detritus and remains of humanity new societies of nature and animal flourish, despite ongoing deforestation and incursion by man. From his window, Zhao records an occurrence that happens every day at 7pm – parrots flocking to a single tree to roost. And he wonders what they know, and what they may know about the future of the place.