Designing Empire: the architecture of Tropical Modernism

An exhibition at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum brings

attention to British modernist architecture deployed across the empire, but

does so with nuance and consideration to the politics beneath aesthetics and design.

Matthew Maganga visited

Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence, discovering a deeply-researched

presentation that starts with architecture but goes deep into politics,

post-colonialism, and climate.

The

architectural legacies of British architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry loom

large over India and parts of West Africa: primarily in the infamous city of

Chandigarh in the former; and in the form of civic and educational structures

with the latter. They are synonymous with the style that came to be known as Tropical

Modernism, a British import to its various colonies in the tropics in the 1950s and 60s. Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence at

the V&A Museum takes this legacy as a starting point, using it as a

launching pad for a broader conversation about modernity and political upheaval

– India and Ghana being the primary case studies.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Framed by a timber brise-soleil-style scenography, the exhibition is broadly divided into three areas: an introductory room outlining the origins of Tropical Modernism as a distinct architectural style, an exploration of Tropical Modernism in India, primarily focused on Le Corbusier’s work in Chandigarh, and finally a display examining Tropical Modernism in a Ghanaian context amidst the journey to their independence, culminating in a three-screen film.

The show makes significant use of standard models of display in architectural exhibitions – models, archival photographs, and architectural plans – but in its curation, and indeed in the language of some of the wall texts, there is a clear intention to cultivate a nuanced understanding of Tropical Modernism and its deployment in British colonies. The exhibition seeks to stray away from a reductive aesthetic analysis, instead working to review how this architectural style was both shaped by colonial ideology and how it acted as a symbol of postcolonial liberation.

The big picture political backdrop of the exhibition narrative is provided in its introduction by photographs and book covers, narrating events such as the 1945 Pan-African Congress. The most political moments in this area, however, come through the more intimate archival material. Drew and Fry’s personal documents are presented alongside a selection of their built work in Nigeria, laying bare the paternalism of the British colonial project in West Africa – adjacent to documentation of the University of Ibadan’s expressive brise-soleil facade are letters that present Drew and Fry’s Tropical design system that omit African architects and builders.

The exhibition text furthers this observation, noting how the two architects came across “no indigenous architecture” in West Africa. It is an arresting juxtaposition, speaking to power imbalances in architectural authorship during colonial rule in Africa, while perhaps making a secondary point about aesthetics – images of Drew and Frye’s West African structures are often presented as an exemplar of appropriate ways of Modern building in the Tropics, without necessarily delving into reductionist European attitudes towards building in the continent.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The relationship between Kwame Nkrumah and Jawaharlal Nehru – respectively Ghana’s and India’s first premiers after independence – foregrounds the India section of the exhibition, with connection between the two nations further amplified by Drew and Fry’s architectural input into the Modernist city of Chandigarh. An explicit manifestation of Le Corbusier’s and Nehru’s ideals of what a modern city should be, Chandigarh has been in equal parts celebrated and criticised. Here, the exhibition again is more interested in nuancing, where Chandigarh can be viewed as a microcosm of internal debates taking place in colonies about large-scale, infrastructural nation-building projects.

A selection of Indian artist Nek Chand’s ceramic sculptures of figures hoisting up pots and building materials – made from material discarded from Chandigarh’s construction process – are an arresting artistic commentary of the scale of both labour and resources used to realise the project. These sculptures are part of a larger body of work, a “secret kingdom” of various figures made by Chand that responded to Corbusier’s gridded plan of the city.

Another response to Corbusier’s masterplan is presented in architectural sketches by Aditya Prakash, an architect who worked with Le Corbusier during Chandigarh’s construction, designing the Chandigarh College of Architecture before later becoming its president. Prakash’s drawings present a Chandigarh that – while Modernist– features room for informal urban processes that respond more closely to India’s cultural context. These subversive artistic and architectural responses are a useful medium for understanding how Indian practitioners critiqued the developments taking place in their country, developments that, in Prakash’s case, they were also intimately involved in. In models, life-size furniture, painting, and film, this section of the show is a particular highlight – coherently laying out the speed and intensity of both building innovation and political events during India’s postcolonial period.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Tropical Modernism then shifts the focus to Ghana, outlining the influence of the Tropical Modernism department of London’s Architectural Association on Ghana’s built environment, the formation of the Kwame Nkrumah Institute of Science and Technology, and concluding with a film previously exhibited at the 2023 Venice Biennale of Architecture (00104). Professor Ola Uduku’s smooth narration and a soundtrack from highlife musician E.T Mensah frame a well-shot documentary triptych film on the birth, life, and afterlife of Tropical Modernism in Ghana. Crucial context is given to some of Drew and Fry’s commissions in Ghana (a community centre, for instance, built as a “pacification effort” following riots against the United Africa Company), but most importantly, there is extensive screen time given for John Owusu Addo, a Ghanaian figure central to a post-colonial adaptation of Tropical Modernism in Ghana.

The documentary – also featuring an interview with Nkrumah’s daughter Samia – is extremely informative in terms of its visual documentation of Ghanaian Tropical Modernist structures and delves into the political pressures that framed these buildings: the colonial windfall of funds that financed Drew and Fry’s projects; the wave of postcolonial optimism that created extensive architectural experimentation in both academic and practice settings; and, ultimately, the decline of Tropical Modernism following economic strife and the deposing of Nkrumah – Owusu-Addo commenting that he was a “very good African, but a very poor Ghanaian”.

![]()

![]()

![]()

However, watching the documentary after viewing the India section of Tropical Modernism does raise questions. There was perhaps room for a more developed critique of the structures displayed and systems at play, such as post-independence the growth of a postcolonial elite, and for example how these then played into architectural aesthetics and architectural taste. Contemporary photographs of students in Owusu-Addo’s Unity Hall are a useful glimpse into how some of the non-neglected 1960’s buildings function today, but reflections on it from a current cohort of KNUST students, for instance, might have provided a useful insight into how younger Ghanaians are reckoning with this architectural legacy today.

But again, these examinations are perhaps better placed within a larger curatorial project. Curated by Christopher Turner and Justine Sambrook, with research from Nana Biamah-Ofosu, Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence is thought-provoking and rich in archival detail, recasting Ghanaian and Indian practitioners as active agents in the adaptation of a Western form of building, albeit one tweaked for a Tropical context. It is an exhibition with a myriad of prescient takeaways for contemporary architects and the general public – from ever-relevant concerns on how to appropriately design for the changing climate, to what one does with these buildings after their use and into neglection, and, crucially, how Tropical Modernism continues to be an extremely mutable term and classification.

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.i-iii

Framed by a timber brise-soleil-style scenography, the exhibition is broadly divided into three areas: an introductory room outlining the origins of Tropical Modernism as a distinct architectural style, an exploration of Tropical Modernism in India, primarily focused on Le Corbusier’s work in Chandigarh, and finally a display examining Tropical Modernism in a Ghanaian context amidst the journey to their independence, culminating in a three-screen film.

The show makes significant use of standard models of display in architectural exhibitions – models, archival photographs, and architectural plans – but in its curation, and indeed in the language of some of the wall texts, there is a clear intention to cultivate a nuanced understanding of Tropical Modernism and its deployment in British colonies. The exhibition seeks to stray away from a reductive aesthetic analysis, instead working to review how this architectural style was both shaped by colonial ideology and how it acted as a symbol of postcolonial liberation.

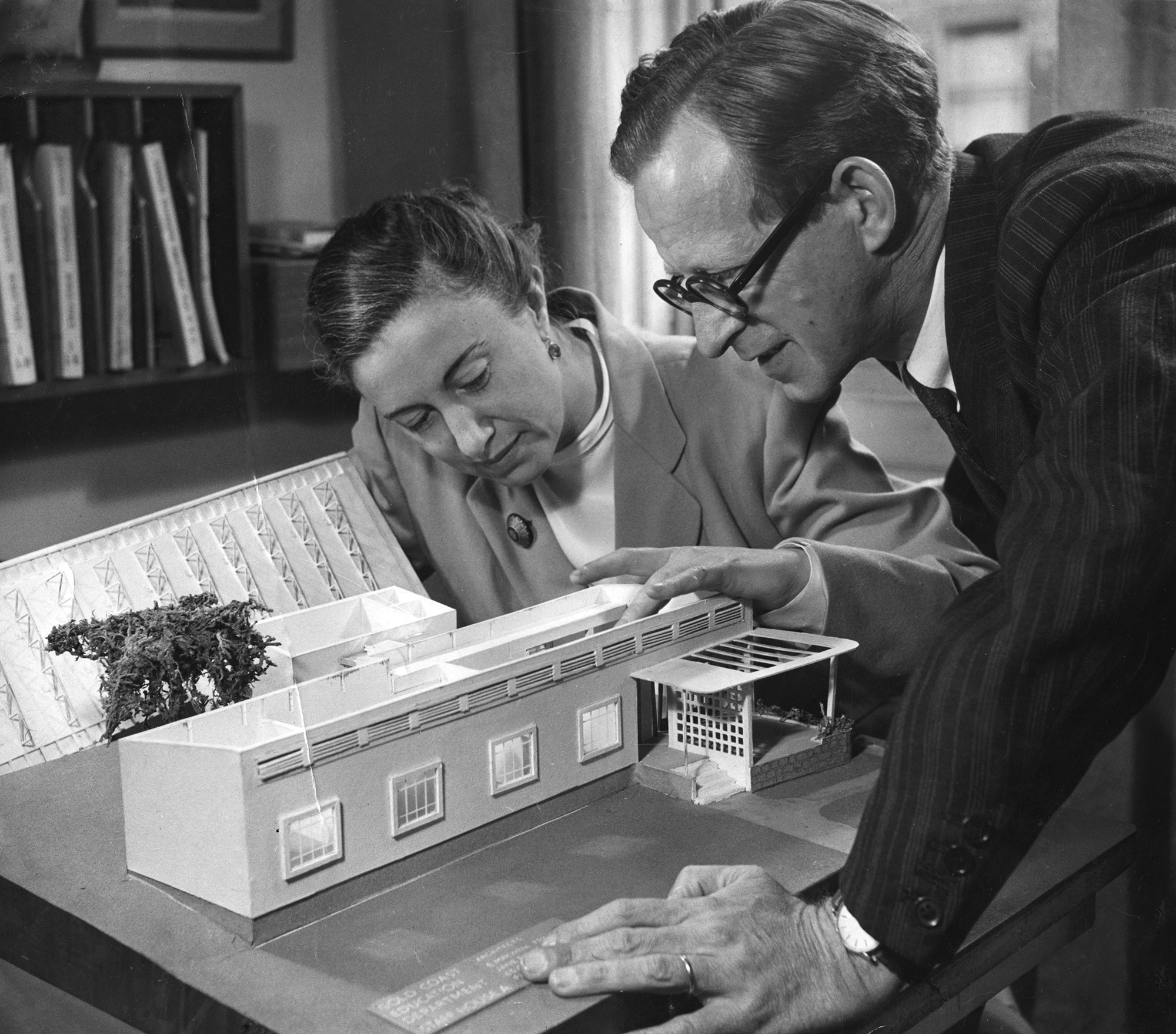

The big picture political backdrop of the exhibition narrative is provided in its introduction by photographs and book covers, narrating events such as the 1945 Pan-African Congress. The most political moments in this area, however, come through the more intimate archival material. Drew and Fry’s personal documents are presented alongside a selection of their built work in Nigeria, laying bare the paternalism of the British colonial project in West Africa – adjacent to documentation of the University of Ibadan’s expressive brise-soleil facade are letters that present Drew and Fry’s Tropical design system that omit African architects and builders.

The exhibition text furthers this observation, noting how the two architects came across “no indigenous architecture” in West Africa. It is an arresting juxtaposition, speaking to power imbalances in architectural authorship during colonial rule in Africa, while perhaps making a secondary point about aesthetics – images of Drew and Frye’s West African structures are often presented as an exemplar of appropriate ways of Modern building in the Tropics, without necessarily delving into reductionist European attitudes towards building in the continent.

figs.iv-vi

The relationship between Kwame Nkrumah and Jawaharlal Nehru – respectively Ghana’s and India’s first premiers after independence – foregrounds the India section of the exhibition, with connection between the two nations further amplified by Drew and Fry’s architectural input into the Modernist city of Chandigarh. An explicit manifestation of Le Corbusier’s and Nehru’s ideals of what a modern city should be, Chandigarh has been in equal parts celebrated and criticised. Here, the exhibition again is more interested in nuancing, where Chandigarh can be viewed as a microcosm of internal debates taking place in colonies about large-scale, infrastructural nation-building projects.

A selection of Indian artist Nek Chand’s ceramic sculptures of figures hoisting up pots and building materials – made from material discarded from Chandigarh’s construction process – are an arresting artistic commentary of the scale of both labour and resources used to realise the project. These sculptures are part of a larger body of work, a “secret kingdom” of various figures made by Chand that responded to Corbusier’s gridded plan of the city.

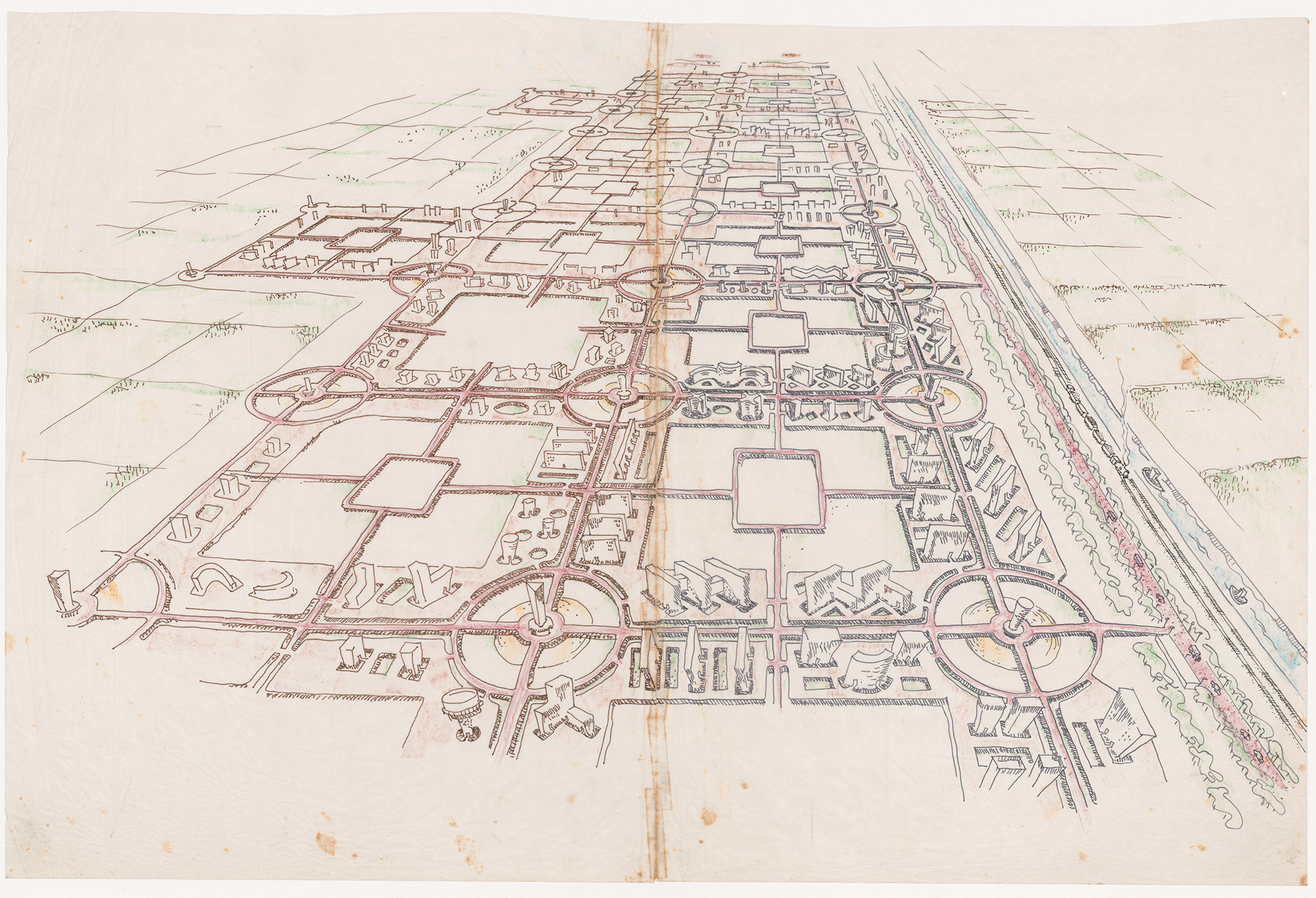

Another response to Corbusier’s masterplan is presented in architectural sketches by Aditya Prakash, an architect who worked with Le Corbusier during Chandigarh’s construction, designing the Chandigarh College of Architecture before later becoming its president. Prakash’s drawings present a Chandigarh that – while Modernist– features room for informal urban processes that respond more closely to India’s cultural context. These subversive artistic and architectural responses are a useful medium for understanding how Indian practitioners critiqued the developments taking place in their country, developments that, in Prakash’s case, they were also intimately involved in. In models, life-size furniture, painting, and film, this section of the show is a particular highlight – coherently laying out the speed and intensity of both building innovation and political events during India’s postcolonial period.

figs.vii-ix

Tropical Modernism then shifts the focus to Ghana, outlining the influence of the Tropical Modernism department of London’s Architectural Association on Ghana’s built environment, the formation of the Kwame Nkrumah Institute of Science and Technology, and concluding with a film previously exhibited at the 2023 Venice Biennale of Architecture (00104). Professor Ola Uduku’s smooth narration and a soundtrack from highlife musician E.T Mensah frame a well-shot documentary triptych film on the birth, life, and afterlife of Tropical Modernism in Ghana. Crucial context is given to some of Drew and Fry’s commissions in Ghana (a community centre, for instance, built as a “pacification effort” following riots against the United Africa Company), but most importantly, there is extensive screen time given for John Owusu Addo, a Ghanaian figure central to a post-colonial adaptation of Tropical Modernism in Ghana.

The documentary – also featuring an interview with Nkrumah’s daughter Samia – is extremely informative in terms of its visual documentation of Ghanaian Tropical Modernist structures and delves into the political pressures that framed these buildings: the colonial windfall of funds that financed Drew and Fry’s projects; the wave of postcolonial optimism that created extensive architectural experimentation in both academic and practice settings; and, ultimately, the decline of Tropical Modernism following economic strife and the deposing of Nkrumah – Owusu-Addo commenting that he was a “very good African, but a very poor Ghanaian”.

figs.x-xii

However, watching the documentary after viewing the India section of Tropical Modernism does raise questions. There was perhaps room for a more developed critique of the structures displayed and systems at play, such as post-independence the growth of a postcolonial elite, and for example how these then played into architectural aesthetics and architectural taste. Contemporary photographs of students in Owusu-Addo’s Unity Hall are a useful glimpse into how some of the non-neglected 1960’s buildings function today, but reflections on it from a current cohort of KNUST students, for instance, might have provided a useful insight into how younger Ghanaians are reckoning with this architectural legacy today.

But again, these examinations are perhaps better placed within a larger curatorial project. Curated by Christopher Turner and Justine Sambrook, with research from Nana Biamah-Ofosu, Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence is thought-provoking and rich in archival detail, recasting Ghanaian and Indian practitioners as active agents in the adaptation of a Western form of building, albeit one tweaked for a Tropical context. It is an exhibition with a myriad of prescient takeaways for contemporary architects and the general public – from ever-relevant concerns on how to appropriately design for the changing climate, to what one does with these buildings after their use and into neglection, and, crucially, how Tropical Modernism continues to be an extremely mutable term and classification.

figs.xiii-xv

Matthew Maganga is a Tanzanian writer and cultural worker currently based in London, UK. He has worked as Curatorial Assistant at the 2023 Sharjah Architecture Triennial and is currently Associate Editor of the Triennial’s catalogue.

Previously, he has worked for ArchDaily as Junior Collaborator, and his writing on architecture and visual culture has been featured on ArchDaily, frieze, The Architectural Review, and the gestalten publication Concrete Jungle: Tropical Architecture and Its Surprising Origins. He is an alumnus of the 2022 Frieze New Writers Programme and 2023 New Architecture Writers Programme. He holds a BA (Hons) in Architecture from the University of Kent.

www.matthewmaganga.com

visit

Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence is

exhibited at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, until 22 September.

Further details available at: www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/tropical-modernism-architecture-and-independence

images

figs.i,v,x,iv Installation shots of Tropical Modernism - Architecture and Independence at the V&A South Kensington (c) Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

fig.ii Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry with a model of one of their many buildings for the Gold Coast, 1945. Image courtesy of RIBA.

fig.iii Sick Hagemeyer shop assistant as a seventies icon posing in front of the United Trading Company headquarters, Accra, 1971 © James Barnor. Courtesy of galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

fig.iv Suresh Kumar, photographer. Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret at Sukhna Lake in Chandigarh, India, circa 1960. Pierre Jeanneret fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture. Gift of Jacqueline Jeanneret. © Suresh Kumar.

fig.vi Illustration from The Architectural Review, 1953. Courtesy RIBA Collections © Gordon Cullen Estate.

fig.vii

Film still of Scott House, Accra by Kenneth Scott -

'Tropical Modernism - Architecture and Independence' © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

fig.viii

Film still of Black Star Square, Accra by Ghana Public Works Department - for 'Tropical Modernism - Architecture and Independence' © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

fig.ix

Film still of Mfantsipim School, Cape Coast by Fry, Drew _ Partners - for 'Tropical Modernism - Architecture and Independence' © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

fig.xi Le Corbusier in Chandigarh with the plan of the city and a model of the Modular Man, his universal system of proportion, 1951 © FDL, ADAGP 2014

fig.xii Aditya Prakash, sketch perspective of Linear City, Chandigarh, India, 1975-1987 © Aditya Prakash fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture. Gift of Vikramaditya Prakash.

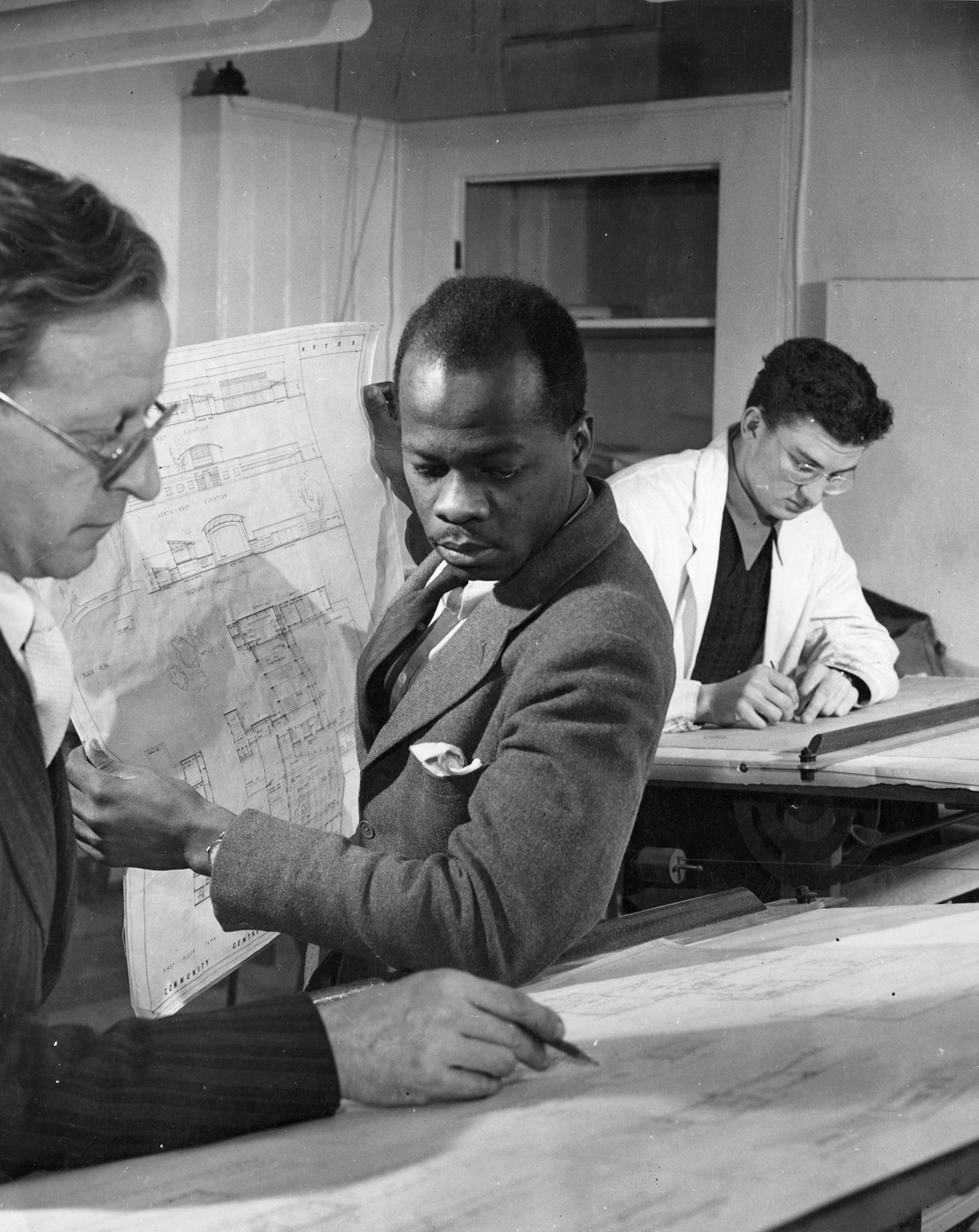

fig.xiii Maxwell Fry in his London office with John Noah, an architect from Sierra Leone, 1940s, Central Office of Information London, Ghana. Courtesy of RIBA.

fig.xiv Boy and concrete screen at University College Ibadan, 1962. Courtesy of RIBA.

publication date

06 May 2024

tags

Africa, Nana Biamah-Ofosu, Brise-soleil, British Empire, Nek Chand, Chandigarh, City, Climate, Colonial, Jane Drew, Maxwell Fry, Ghana, Imperial, India, Kwame Nkrumah Institute of Science and Technology, Le Corbusier, Matthew Maganga, E.T Mensah, Modernism, Jawaharlal Nehru, Nigeria, Kwame Nkrumah, Samia Kkrumah, John Owusu Addo, Pan-African Congress, Politics, Aditya Prakash, Justine Sambrook, Tropical Modernism, Christopher Turner, Urban, Venice Biennale, V&A, Victoria & Albert Museum, West Africa

images