Venice 2024:

Iceland’s

Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir cartoonishly shows invisible systems

In our latest report from the 2024 Venice Biennale of Art, we look at the Icelandic pavilion where Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir has absurd fun while creating a 21st century update of Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau. Using the mundane systems of art production as the work itself, Birgisdóttir creates a subtle & uncanny space.

February 2022 was a different age. A lot has happened in the

25 months since, not just for recessed.space which has grown from just a few

articles to now nearly 200 in a growing archive of art and architecture, but in

the world more widely. On 02 February 2022, in one of the first pieces on the

platform (00011) we reported from Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir’s exhibition at GES-2,

a huge (in scale and expense) new arts centre designed by Renzo Piano for V-A-C

Foundation. Birgisdóttir’s playful interruption of the white walls GES-2’s

basement gallery, which saw capitalist objects from drying racks to plastic

garden furniture buried into the plaster walls, was a highlight from the

opening series of projects headlined and co-curated by fellow Icelandic artist,

Ragnar Kjartansson.

GES-2 was a conversion of an historic, redundant gas power station in the heart of Moscow. Three weeks after we reported on Birgisdóttir’s exhibition, Russia invaded Ukraine. All the items the artist concealed within the gallery walls were purchased from international retailers and all delivered to the museum, presenting a broken time-capsule of everyday mundanity wrought in disposable and cheaply made objects, but also invoking the international trade network and how Russia, since the lowering of the hammer and sickle over the Kremlin in late 1991, had become a deep part of that network.

![]()

Two years of bloody conflict later, the trade network between much of the world – particularly the Global North – and Russia has nearly stopped, other than oil sales funnelled through Luxembourg and a grey-market of luxury goods still finding their way to the upper-middle classes and oligarchs. Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir’s practice, though, is still profoundly interested in the networks and structures of late-capitalism, with the artist selected to present for her country with the installation That’s a Very Large Number — A Commerzbau by Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir, curated by Dan Byers. It takes something as violent and aggressive as Putin’s actions for a country to even be semi-extracted from the global markets, such a deep part of our political and social construct that they are, and Iceland’s presentation seeks to shed a little light on those networks through an artistic lens.

There are aesthetic ties to the work presented at GES-2 and seen by only a handful of people before the exhibitions were pulled and the arts space was turned over less politically interesting and international work. In Iceland’s partitioned white cube in the Arsenale, the artist has similarly embedded objects into the walls, some of which are cartoonishly large while others so discreet they may not be spotted at first. Many of the objects are versions of domestic items from a child’s dollhouse, scanned, enlarged, then 3D printed to create uncanny, smooth and dislocated objects of trainee domestic capitalism. A pizza, dentistry equipment, a steak, and half a lettuce take on new identities losing much detail, but gaining new ones also – the steak has the word “THAILAND” embossed on one side, “CHINA” is on the back of the pizza.

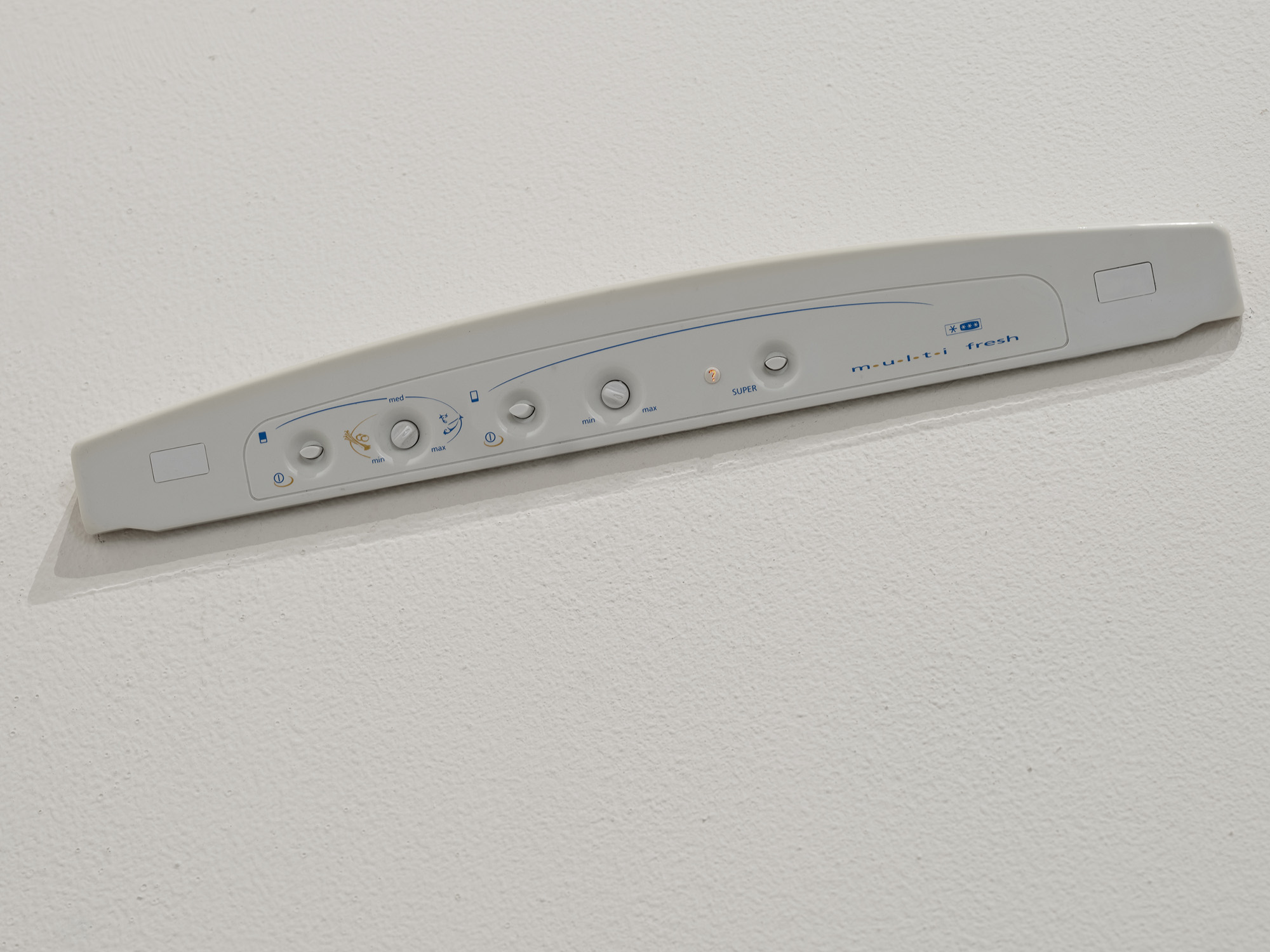

Mirroring the Arsenale’s arched window, but at a skew, is a massive version of some cardboard packaging but here, instead of being thrown away, it is celebrated and recognised as a cultural object as valuable as the unknown consumer item it was once the backing to. The control panels from a home printer and fridge, also embedded into the wall, relentlessly blink error warnings. Something has gone wrong.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

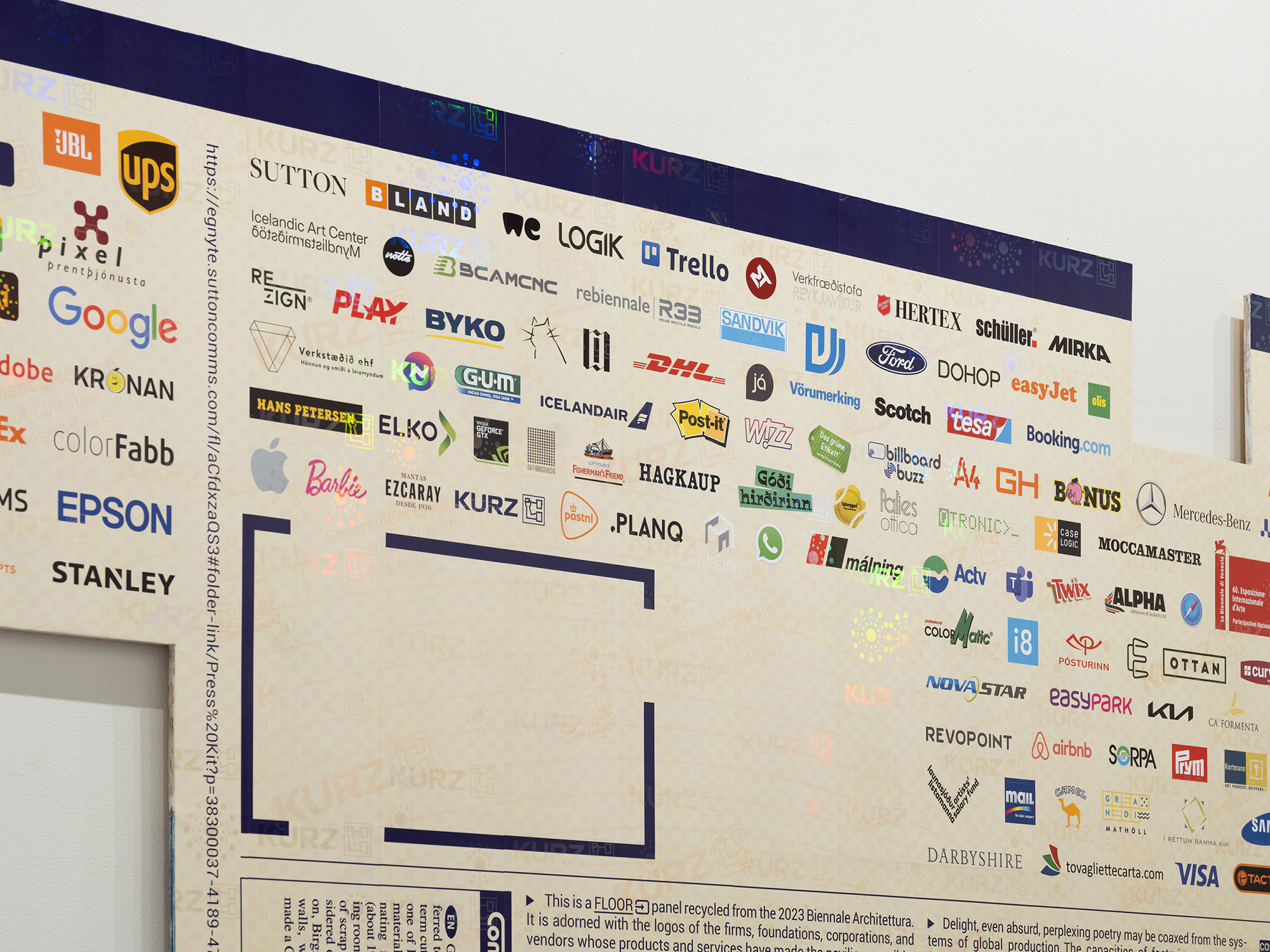

A giant wall panel, which recycles the floor of Argentina’s 2023 Architecture Biennale presentation, lists every firm and organisation that led to the creation of the work. Art organisations who front such projects – the Venice Biennale logo is present, as is Birgisdóttir’s Reykjavík gallery, i8 – sit alongside art-ecosystem elements often invisible at the surface, such as PR company Sutton and framers Darbyshire. But, most logos are from everyday companies from Apple to Scotch tape, DHL to Zoom, reminding that the art world, however special it tries to appear, is just another producer of content in the wider world of content. The logo of Kurz, a company who produce holograms for bank notes, sparkles back in sharp gallery lighting. The arrangement is chaotic and democratic, no special hierarchy of importance, prestige, nation state, or logo aesthetic.

Through the window, across a canal, an electronic billboard blinks back. As with the smooth, enlarged dollhouse items, a visitor may not notice it at first but it’s another transnational connection, Birgisdóttir having set up a camera pointing at a digital advert in the Iceland capital, but we only ever see a square fragment of it and not the wider commercial context. Unidentifiable moments of text and logos flash back, maybe a bit of grinning face, perhaps a product.

The subtitle of the work, A Commerzbau by Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir, is a nod to dadaist Kurt Schwitters who created immersive collages from found items. The German artist adopted the word “Merz” for his practice having used a fragment of a paper headlined “Commerz Bank”, also created Merzbau – Merz Building – as immersive architectural collages. Here, Birgisdóttir repairs the broken word and reintroduces “Com-” to it, as if trying to recognise the contract commerce has with everything (especially making and showing art) and trying to repair the invisible depths of abstract and conceptual art practices.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Buried within such a plein air critique of capitalism, consumerism, and conceptual art, is the idea of value. Had Iceland won the Golden Lion instead of Australia (see 00194) the financial value of each component within That’s a Very Large Number would have increased greatly, even though they remain constructs of international networks of making, communication, and delivery. Logos, adverts, packaging, and toys to train children to be adults are used to preserve and project a value beyond financial, devoid of process, labour, and deeper meaning, a phantasmagoric presence of commodity.

The panel of logos in Iceland’s presentation is an artwork, but it is also an exaggerated version of the contextual information wall presented alongside the normal art objects. It is within and apart from its categorisation. Here, the artist is not presented as some magical being creating objects with aura from a garret, but acknowledges they simply organise elements of consumer society into slightly absurd objects that may seem separate to other systems, yet as deeply implicated as any other consumer goods.

GES-2 was a conversion of an historic, redundant gas power station in the heart of Moscow. Three weeks after we reported on Birgisdóttir’s exhibition, Russia invaded Ukraine. All the items the artist concealed within the gallery walls were purchased from international retailers and all delivered to the museum, presenting a broken time-capsule of everyday mundanity wrought in disposable and cheaply made objects, but also invoking the international trade network and how Russia, since the lowering of the hammer and sickle over the Kremlin in late 1991, had become a deep part of that network.

fig.i

Two years of bloody conflict later, the trade network between much of the world – particularly the Global North – and Russia has nearly stopped, other than oil sales funnelled through Luxembourg and a grey-market of luxury goods still finding their way to the upper-middle classes and oligarchs. Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir’s practice, though, is still profoundly interested in the networks and structures of late-capitalism, with the artist selected to present for her country with the installation That’s a Very Large Number — A Commerzbau by Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir, curated by Dan Byers. It takes something as violent and aggressive as Putin’s actions for a country to even be semi-extracted from the global markets, such a deep part of our political and social construct that they are, and Iceland’s presentation seeks to shed a little light on those networks through an artistic lens.

There are aesthetic ties to the work presented at GES-2 and seen by only a handful of people before the exhibitions were pulled and the arts space was turned over less politically interesting and international work. In Iceland’s partitioned white cube in the Arsenale, the artist has similarly embedded objects into the walls, some of which are cartoonishly large while others so discreet they may not be spotted at first. Many of the objects are versions of domestic items from a child’s dollhouse, scanned, enlarged, then 3D printed to create uncanny, smooth and dislocated objects of trainee domestic capitalism. A pizza, dentistry equipment, a steak, and half a lettuce take on new identities losing much detail, but gaining new ones also – the steak has the word “THAILAND” embossed on one side, “CHINA” is on the back of the pizza.

Mirroring the Arsenale’s arched window, but at a skew, is a massive version of some cardboard packaging but here, instead of being thrown away, it is celebrated and recognised as a cultural object as valuable as the unknown consumer item it was once the backing to. The control panels from a home printer and fridge, also embedded into the wall, relentlessly blink error warnings. Something has gone wrong.

figs.ii-vi

A giant wall panel, which recycles the floor of Argentina’s 2023 Architecture Biennale presentation, lists every firm and organisation that led to the creation of the work. Art organisations who front such projects – the Venice Biennale logo is present, as is Birgisdóttir’s Reykjavík gallery, i8 – sit alongside art-ecosystem elements often invisible at the surface, such as PR company Sutton and framers Darbyshire. But, most logos are from everyday companies from Apple to Scotch tape, DHL to Zoom, reminding that the art world, however special it tries to appear, is just another producer of content in the wider world of content. The logo of Kurz, a company who produce holograms for bank notes, sparkles back in sharp gallery lighting. The arrangement is chaotic and democratic, no special hierarchy of importance, prestige, nation state, or logo aesthetic.

Through the window, across a canal, an electronic billboard blinks back. As with the smooth, enlarged dollhouse items, a visitor may not notice it at first but it’s another transnational connection, Birgisdóttir having set up a camera pointing at a digital advert in the Iceland capital, but we only ever see a square fragment of it and not the wider commercial context. Unidentifiable moments of text and logos flash back, maybe a bit of grinning face, perhaps a product.

The subtitle of the work, A Commerzbau by Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir, is a nod to dadaist Kurt Schwitters who created immersive collages from found items. The German artist adopted the word “Merz” for his practice having used a fragment of a paper headlined “Commerz Bank”, also created Merzbau – Merz Building – as immersive architectural collages. Here, Birgisdóttir repairs the broken word and reintroduces “Com-” to it, as if trying to recognise the contract commerce has with everything (especially making and showing art) and trying to repair the invisible depths of abstract and conceptual art practices.

figs.vii-ix

Buried within such a plein air critique of capitalism, consumerism, and conceptual art, is the idea of value. Had Iceland won the Golden Lion instead of Australia (see 00194) the financial value of each component within That’s a Very Large Number would have increased greatly, even though they remain constructs of international networks of making, communication, and delivery. Logos, adverts, packaging, and toys to train children to be adults are used to preserve and project a value beyond financial, devoid of process, labour, and deeper meaning, a phantasmagoric presence of commodity.

The panel of logos in Iceland’s presentation is an artwork, but it is also an exaggerated version of the contextual information wall presented alongside the normal art objects. It is within and apart from its categorisation. Here, the artist is not presented as some magical being creating objects with aura from a garret, but acknowledges they simply organise elements of consumer society into slightly absurd objects that may seem separate to other systems, yet as deeply implicated as any other consumer goods.