Venice 2024: an interview with Australia’s Golden Lion

winner Archie Moore & architect Kevin O’Brien

The winning national pavilion of this year’s Venice Biennale

of art was awarded to Australia for their pavilion looking at indigenous family

history by artist Archie Moore. Will Jennings spoke to Moore & the pavilion’s

architect, Kevin O’Brien, to discover more about the project and the design behind

it.

The winner of this year’s Venice Biennale of Art’s Golden Lion for best National Participation went to Archie Moore and his project for the Australia pavilion, the first time the nation had received the award. Moore’s work, kith and kin, was curated by Ellie Buttrose and comprises two main elements: a meticulously hand-drawn family tree on the four internal walls of the pavilion, and a central table over a pool of water on which piles of stacked white documents covered like a landscape. recessed.space’s editor, Will Jennings, spoke to the Archie Moore and the project’s architect, Kevin O’Brien.

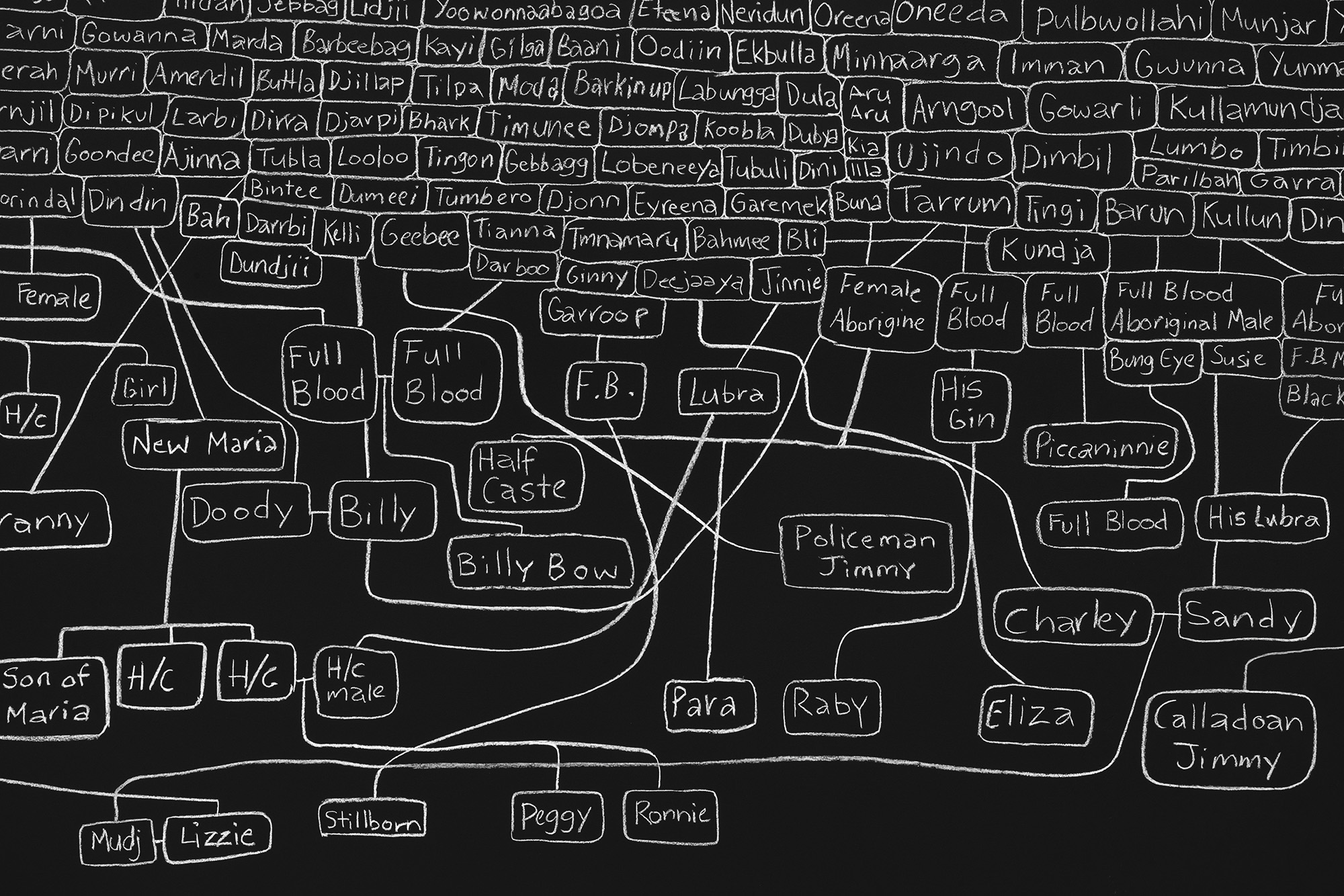

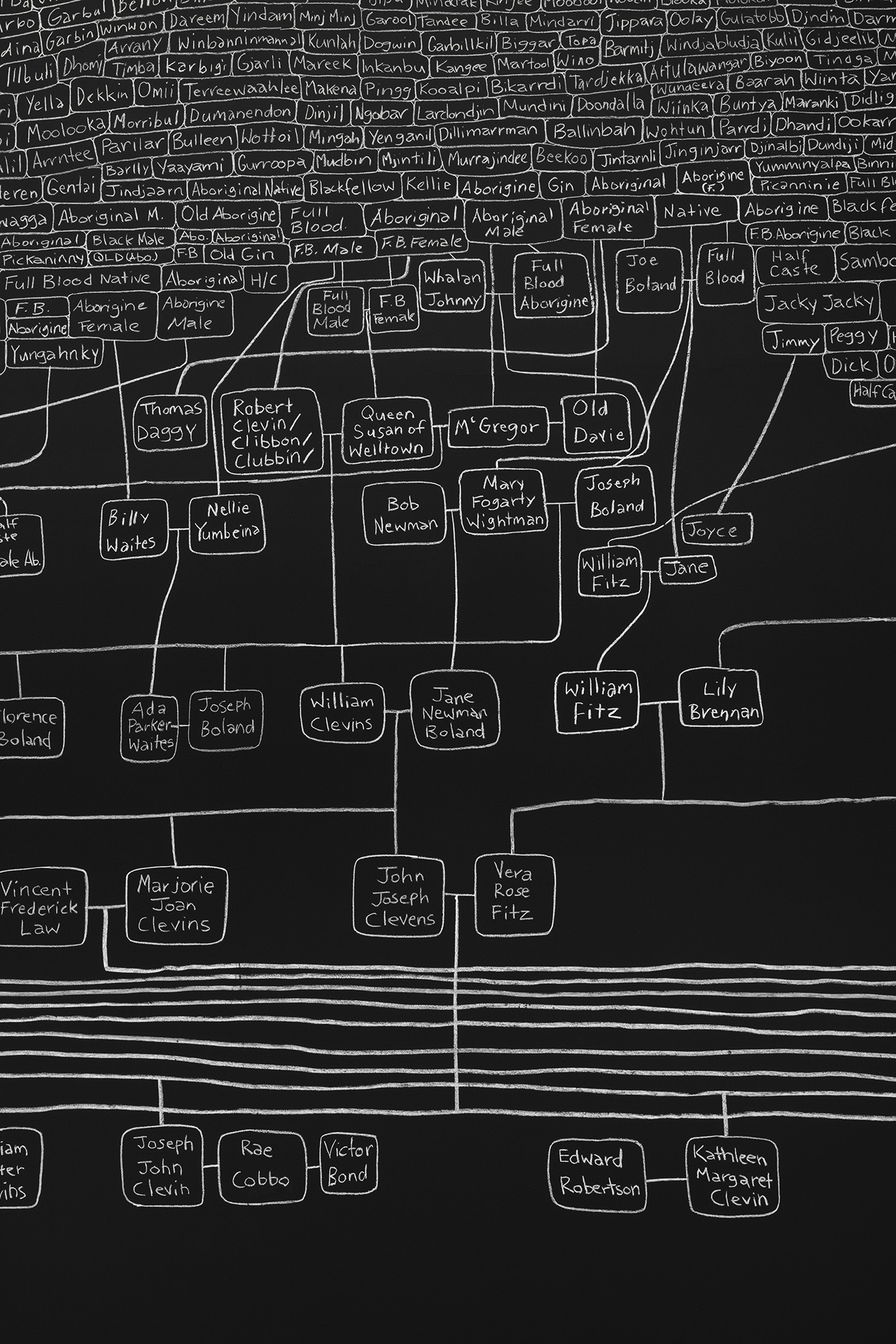

kith and kin is a project that speaks to Moore’s personal and family

history, but through it looks at the Aboriginal experience of identity,

ancestry, familial structures, and colonial practices and violence. The names

covering the walls number into the thousands, each an individual discovered

through deep research through a variety of archives, though with many gaps

where records were not made or retained. The names themselves also reflect the

relationship of individuals to the state, archives, and the coming together of

different modes of considering family and history. More recent names, at the

bottom of the tree, fit into a Western naming logic, and as the tree rises up

the wall names become derogatory, then shortened, and then fit an Aboriginal

system of kinship.

In Venice, recessed.space spoke to both Archie Moore and the

architect of the project, Kevin O’Brien, a Principal at BVN, an Australian firm

with offices in Sydney, Brisbane, London, and New York. Moore and O’Brien have

worked on projects in the past, and while both the work and architectural

setting may at first appear simple, both required deep thinking and work to

create that sense of levity: Moore spending many hours in the archives before months in Venice writing the family tree onto the black walls; and

O’Brien deeply considering the existing Denton Corker Marshall-designed

pavilion building before collaborating with Moore with a nuanced approach to design to best support and amplify the work and its deeper meanings.

ARCHIE MOORE

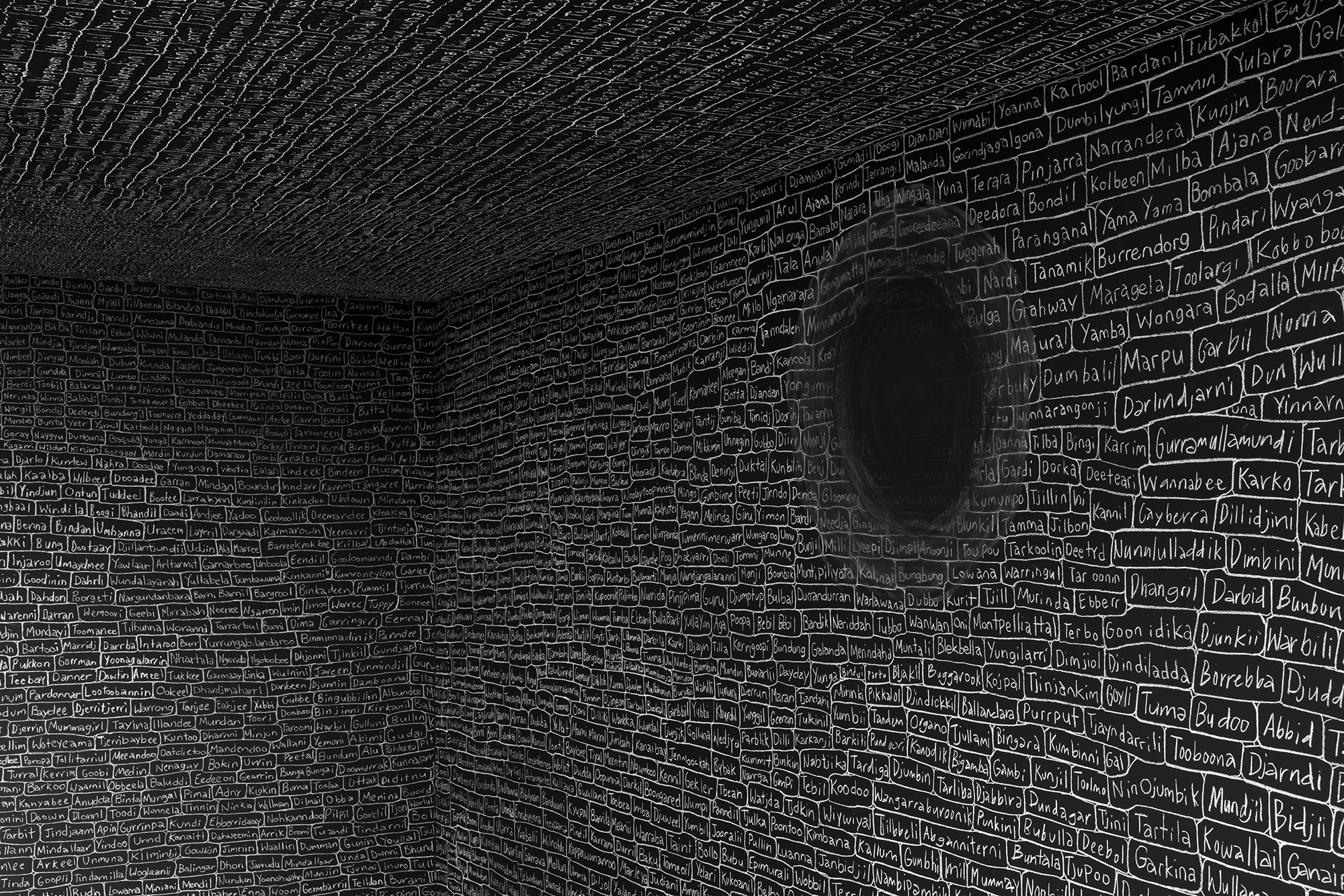

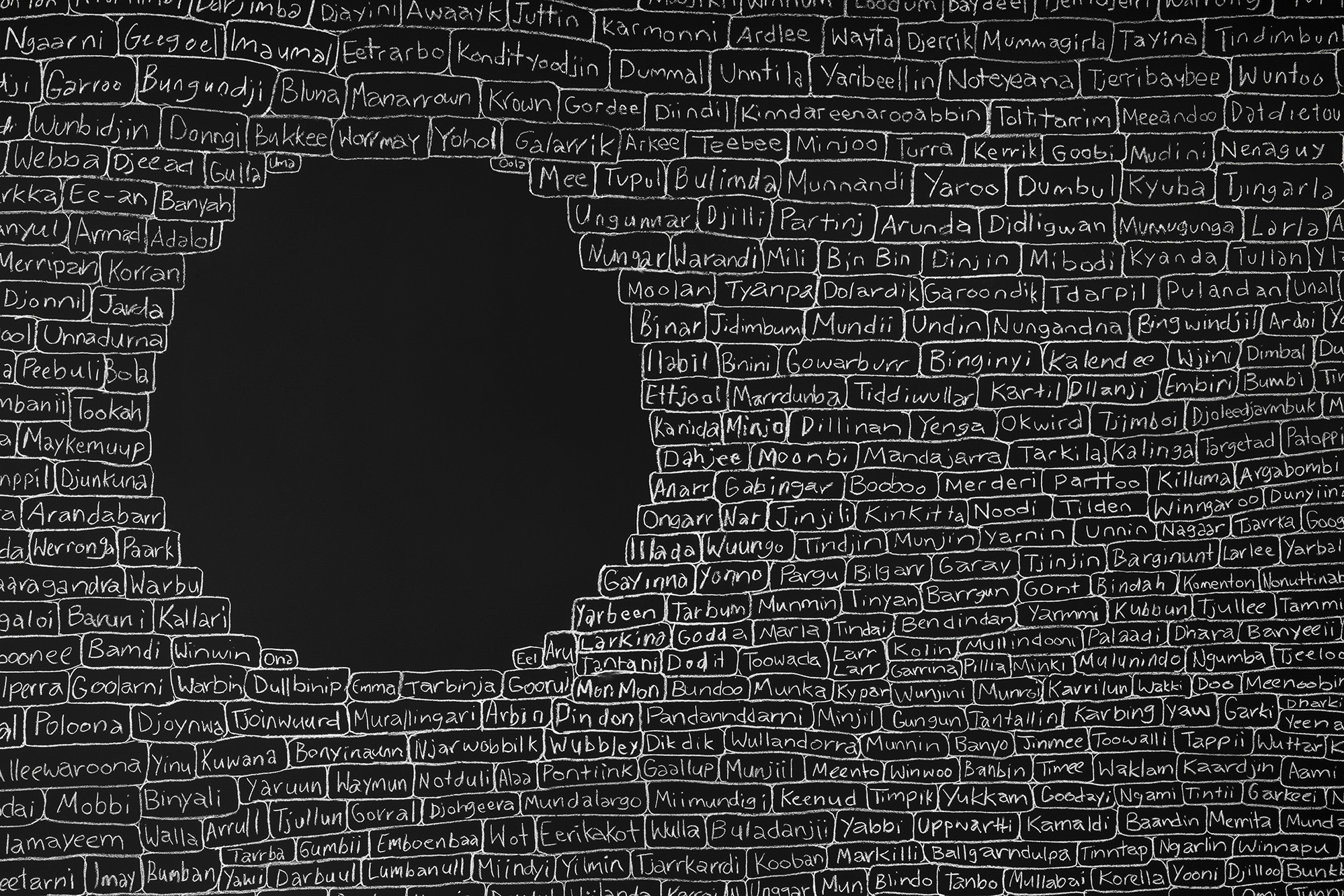

“The installation is intended to be like a shrine or a memorial, a place for quiet reflection and remembrance. The walls of the pavilion are painted in blackboard paint and I drew on my family tree in chalk, or as much as I know of my tree going back as far as I can on the Aboriginal side.”

“And as the tree goes beyond, to what is intended to be 65,000 years – t he accepted amount of time Aboriginal people have lived on the Australian continent – it continues off the wall and onto the ceiling. It’s as if you're looking up into the night sky and the stars, and there are places between the stars in the sky, places where the kamilaroi side of my Aboriginal lineage believed they went after death.”

“The installation is intended to be like a shrine or a memorial, a place for quiet reflection and remembrance. The walls of the pavilion are painted in blackboard paint and I drew on my family tree in chalk, or as much as I know of my tree going back as far as I can on the Aboriginal side.”

“And as the tree goes beyond, to what is intended to be 65,000 years – t he accepted amount of time Aboriginal people have lived on the Australian continent – it continues off the wall and onto the ceiling. It’s as if you're looking up into the night sky and the stars, and there are places between the stars in the sky, places where the kamilaroi side of my Aboriginal lineage believed they went after death.”

ARCHIE MOORE

“The names in the tree give you an idea of time as well as how language is used. Down at the bottom of the tree, people have two or three names that are very European sounding – both my grandparents have German surnames and I'm not sure where they originate from. But then, above that is the next layer of the tree where a person may have one name, a shortened version of their proper name, like Billy from William or Tommy from Thomas, and then as you get higher it's just a description and not a name. It'll be like black, coloured, or tall half caste, these derogatory names. I've seen these on records – it’s a person, it's someone connected to my family, but it's just a description and I don't know what their real name is. Then above that it goes back to a singular name, but this time it's indigenous.”

“The names in the tree give you an idea of time as well as how language is used. Down at the bottom of the tree, people have two or three names that are very European sounding – both my grandparents have German surnames and I'm not sure where they originate from. But then, above that is the next layer of the tree where a person may have one name, a shortened version of their proper name, like Billy from William or Tommy from Thomas, and then as you get higher it's just a description and not a name. It'll be like black, coloured, or tall half caste, these derogatory names. I've seen these on records – it’s a person, it's someone connected to my family, but it's just a description and I don't know what their real name is. Then above that it goes back to a singular name, but this time it's indigenous.”

KEVIN O’BRIEN

“The two lighting rings have different intensities and there was really interesting discussions around how dark or how bright it should be, and Archie got to the point where the idea is so when you come in your eyesight is still adjusting from the outside, but by the time you actually get the full distance around your eyes have adjusted. Then you get to a bench and you’re ready to sit down, your eyes should be alright and then you can actually pick up the rest of the detail in the ceiling. We were trying to get this whole metaphysical experience happening through the lighting.”

“The two lighting rings have different intensities and there was really interesting discussions around how dark or how bright it should be, and Archie got to the point where the idea is so when you come in your eyesight is still adjusting from the outside, but by the time you actually get the full distance around your eyes have adjusted. Then you get to a bench and you’re ready to sit down, your eyes should be alright and then you can actually pick up the rest of the detail in the ceiling. We were trying to get this whole metaphysical experience happening through the lighting.”

ARCHIE MOORE

“In the centre of the room are coroners reports into Aboriginal deaths in police custody. From the Royal Commission final report, an independent investigation into why Aboriginal people were dying at the hands of police while in custody, there were over 300 recommendations on how to address this problem – and none of those recommendations have been implemented so far. Included amongst those documents are nineteen family documents I found in the archives that talk about my family, that talk about what every Aboriginal family has experienced: being under surveillance or needing permission to marry another Aboriginal person.”

“In the centre of the room are coroners reports into Aboriginal deaths in police custody. From the Royal Commission final report, an independent investigation into why Aboriginal people were dying at the hands of police while in custody, there were over 300 recommendations on how to address this problem – and none of those recommendations have been implemented so far. Included amongst those documents are nineteen family documents I found in the archives that talk about my family, that talk about what every Aboriginal family has experienced: being under surveillance or needing permission to marry another Aboriginal person.”

ARCHIE MOORE

“Underneath the documents there's a pool of water that’s a feature of memorials, and if you look into that pool of water you will see the tree reflected as you also see the documents – it’s a way of saying that they're real people. I have also kept part of the window open – I think every other Australia pavilion has had the window completely filled in, but I want viewers to look out into the canal as it flows into the lagoon and into the sea and into the rest of the world, eventually surrounding the continent of Australia, as a way to show connection between everyone.”

“Underneath the documents there's a pool of water that’s a feature of memorials, and if you look into that pool of water you will see the tree reflected as you also see the documents – it’s a way of saying that they're real people. I have also kept part of the window open – I think every other Australia pavilion has had the window completely filled in, but I want viewers to look out into the canal as it flows into the lagoon and into the sea and into the rest of the world, eventually surrounding the continent of Australia, as a way to show connection between everyone.”

KEVIN O’BRIEN

“The window works in two directions. The idea of not closing it fully, but pulling it down so we are squeezing, compressing the light in one direction, also frames the view directly into the water as a way of connecting in terms of the story that Archie spoke of, as a way of connecting all the way back to where we are from. That also architecturally sets the character of the space, so it has a memorial-like calmness in the space and for me that sits really well with the architecture of the building because it has a heavy brooding silent kind of presence.”

“The window works in two directions. The idea of not closing it fully, but pulling it down so we are squeezing, compressing the light in one direction, also frames the view directly into the water as a way of connecting in terms of the story that Archie spoke of, as a way of connecting all the way back to where we are from. That also architecturally sets the character of the space, so it has a memorial-like calmness in the space and for me that sits really well with the architecture of the building because it has a heavy brooding silent kind of presence.”

ARCHIE MOORE

“There are also three holes in the tree to represent a disruption to the genealogical lineage. It might be a massacre perpetrated by white people on Aboriginal people. It may be a viral outbreak – smallpox was a disease that was introduced to Australia when people arrived and indigenous people didn't have resistance or immunities. Or the hole could also represent information that has been destroyed or erased intentionally or accidentally, or information that hasn't been recorded in the first place.”

“There are also three holes in the tree to represent a disruption to the genealogical lineage. It might be a massacre perpetrated by white people on Aboriginal people. It may be a viral outbreak – smallpox was a disease that was introduced to Australia when people arrived and indigenous people didn't have resistance or immunities. Or the hole could also represent information that has been destroyed or erased intentionally or accidentally, or information that hasn't been recorded in the first place.”

KEVIN O’BRIEN

“The table that is meant to help keep the documents afloat – so it's not meant to be a table with documents on it. We did a lot of work to try to cantilever the table as much as possible and to use the structure itself to hold the parts locking together as one. We really think about where we position people, so how people move around the space, where they stop, what their posture is, what you want them to see when they're sitting down, it's all been calibrated in a particular way.”

“Another thing is the distance to the edge of the documents. It's just at the right height so you can't quite read them. The documents are just out of reach. First Nation people that have gone looking for documents in the archival system in Australia, we know they exist but just couldn’t get hold of them, they're just out of reach.”

“The table that is meant to help keep the documents afloat – so it's not meant to be a table with documents on it. We did a lot of work to try to cantilever the table as much as possible and to use the structure itself to hold the parts locking together as one. We really think about where we position people, so how people move around the space, where they stop, what their posture is, what you want them to see when they're sitting down, it's all been calibrated in a particular way.”

“Another thing is the distance to the edge of the documents. It's just at the right height so you can't quite read them. The documents are just out of reach. First Nation people that have gone looking for documents in the archival system in Australia, we know they exist but just couldn’t get hold of them, they're just out of reach.”

ARCHIE MOORE

“The title is kith and kin, and most English speaking people will be familiar with this phrase as meaning friends and family. When I was looking into the definition, I saw there was a much earlier old English definition of kith meaning countrymen or of one's own country or land. So I was drawn to this idea, seeing that English people have a very indigenous way of thinking about the land, or belonging to the land, and that they were thinking this way in the 1300s on their own landmass, England.”

“I've used the website ancestry.com, but there was also an anthropologist that visited my great grandmother’s smal country town in 1938. He was a part of a wider expedition across the whole of Australia and interviewed a lot of Aboriginal people, asking who their parents were, who their siblings and children were, and he drew family trees in a western anthropological way. So, this references that, but as it gets larger with other ancestors it takes a more indigenous look, so I am comparing these two ideas of families – Western nuclear family ideas and Aboriginal people who had more than one mother and father in a kinship system.”

“The title is kith and kin, and most English speaking people will be familiar with this phrase as meaning friends and family. When I was looking into the definition, I saw there was a much earlier old English definition of kith meaning countrymen or of one's own country or land. So I was drawn to this idea, seeing that English people have a very indigenous way of thinking about the land, or belonging to the land, and that they were thinking this way in the 1300s on their own landmass, England.”

“I've used the website ancestry.com, but there was also an anthropologist that visited my great grandmother’s smal country town in 1938. He was a part of a wider expedition across the whole of Australia and interviewed a lot of Aboriginal people, asking who their parents were, who their siblings and children were, and he drew family trees in a western anthropological way. So, this references that, but as it gets larger with other ancestors it takes a more indigenous look, so I am comparing these two ideas of families – Western nuclear family ideas and Aboriginal people who had more than one mother and father in a kinship system.”

KEVIN O’BRIEN

“This is an arts endeavour, so the role of the architect is to sit behind that, and if you are noticing anything that's an architectural move then it means the art hasn't come forward enough. So, being very mindful that we've collaborated in the past, we were aware of the idea Archie was pursuing, and we worked as much as possible to make the architectural techniques to be in service to it.”

“I think it's one of the the first exhibition architectures I've seen that isn't trying to fill the room, but it just creates a tension between the thing in the middle and the rest of the room at just the right charge and tension between what's on the wall and what's on the table.”

“This is an arts endeavour, so the role of the architect is to sit behind that, and if you are noticing anything that's an architectural move then it means the art hasn't come forward enough. So, being very mindful that we've collaborated in the past, we were aware of the idea Archie was pursuing, and we worked as much as possible to make the architectural techniques to be in service to it.”

“I think it's one of the the first exhibition architectures I've seen that isn't trying to fill the room, but it just creates a tension between the thing in the middle and the rest of the room at just the right charge and tension between what's on the wall and what's on the table.”

abo

Archie Moore (b. 1970, toowoomba) is a Kamilaroi/Bigambul artist who works across media in conceptual, research-based portrayals of self and national histories. His ongoing interests include key signifiers of identity (skin, language, smell, home, genealogy, flags), the borders of intercultural understanding and misunderstanding, and the wider concerns of racism. recent solo exhibitions by Archie include: Pillors of Democracy, 2023, Cairns Art Gallery; Dwelling (Victorian Issue), 2022, Gertrude Contemporary, Melbourne; The Colour Line: Archie Moore & W.E.B. du Bois, 2021, University of New South Wales Galleries, Sydney; and Archie Moore 1970–2018, 2018, Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane.

Significant recent group exhibitions comprise: Ever Present: First Peoples Art of Australia, 2022, National Gallery of Singapore; Embodied Knowledge: Queensland Contemporary Art, 2022, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane; Un/Learning Australia, 2021, Aeoul Museum of Art; Indigenous Art Triennial, 2017, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; The National: New Australian Art, 2017, Carriageworks, Sydney; and Biennale of Sydney, 2016, Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney. in 2018, Archie’s United Neytions was permanently installed at Sydney Airport’s International Terminal.

Archie’s artworks are held in major public collections across australia including: Artbank; Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane; Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne; Murray Art Museum Albury; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; National Portrait Gallery, Canberra; Newcastle Art Gallery; Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane; Queensland University

of technology art museum, brisbane; University of Queensland Art Museum, Brisbane; and University of Sydney; and University of Technology sydney. His art is also held in the collection of Fondation Opale, Lens, Switzerland.

Kevin O’Brien (1972) is an architect practising in Queensland, Australia, noted for drawing on indigenous concepts of space in his work. O'Brien was born in Melbourne, Australia, graduating from the University of Queensland with a Bachelor of Architecture degree in 1995. In 2006, he studied Aboriginality and Architecture, gaining a Master of Philosophy under Paul Memmott.

O'Brien established Kevin O'Brien Architects in Brisbane, completing projects throughout several Australian states. In 2000, he travelled around the Pacific Rim as a Churchill Fellow to investigate regional construction strategies in indigenous communities.

O'Brien directed the Finding Country Exhibition at the 13th Venice Architecture Biennale in 2012 and was appointed as a Professor of Design at the Queensland University of Technology.

Kevin O'Brien Architects merged with BVN Architecture in 2018.

www.bvn.com.au/person/kevin-o-brien

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

O'Brien established Kevin O'Brien Architects in Brisbane, completing projects throughout several Australian states. In 2000, he travelled around the Pacific Rim as a Churchill Fellow to investigate regional construction strategies in indigenous communities. O'Brien directed the Finding Country Exhibition at the 13th Venice Architecture Biennale in 2012 and was appointed as a Professor of Design at the Queensland University of Technology. Kevin O'Brien Architects merged with BVN Architecture in 2018.

www.bvn.com.au/person/kevin-o-brien