Empty chairs & liminal Spaces: Alexandra Metcalf’s Gaaaaaaasp

Initially transformed by 6a architects from a Georgian townhouse

into a John Soane-inspired contemporary art gallery, The Perimeter has been reimagined again by Alexandra Metcalf into a nostalgic waiting room for her

show Gaaaaaaasp. Rochelle Roberts visited to find paintings &

sculptures that evoke familiarity & therapy but an ambiguous & uncanny

insert of institution into the domestic.

On display at The Perimeter gallery in

Bloomsbury, Alexandra Metcalf’s exhibition Gaaaaaaasp brings together

paintings, sculpture, and installations. Drawing on a range of references – from

the Victorian era, 1960s to 70s, and the present day – Metcalf transforms the

gallery into psychological spaces to explore themes of illness, care, autonomy,

and control through time.

![]()

![]()

In the first room, Metcalf recreates the waiting room of a hospital or clinic. The room invites the viewer to interact with it: to sit down on one of the upholstered wooden chairs (sourced from a church), to watch the TV perched on a high shelf in the corner of the room, to assume the role of patient. Although unspecified, we might consider this room to be the waiting room of a Victorian psychiatric facility or asylum – in the accompanying exhibition catalogue, an essay by Jennifer Higgie outlines Metcalf’s interest in the figure of “Crazy Jane”, an archetypal “mad woman” derived from Shakespeare’s Ophelia and popular during the Romantic period, and her portrait painted by Richard Dadd, the Victorian artist who was admitted to Bethlem psychiatric hospital (also known as Bedlam) after murdering his father while believing him to be an impostor. Poor Richard, locked in the asylum, so full of waiting rooms, as Higgie writes.[i]

But Metcalf is not only interested in this period of history. Through her immersive environments, she slips between time, stitching together the past and the present, familiarity and unfamiliarity, the domestic and the institutional. What results is a kind of sensory collage, an in-betweenness that leaves the viewer not quite in one place or the other. The 1960s geometric wallpaper juxtaposed with the Victorian wooden wainscoting panelling feels old-fashioned, while the 90s silver box TV has its own nostalgia. The LED ceiling panels are reminiscent of hospitals or offices – cold, unwelcoming environments that have an air of detachment. Waiting rooms, themselves, are liminal spaces, and this lends itself well to Metcalf’s playful meshing together of different eras.

![]()

![]()

Like many waiting rooms, Metcalf’s is lined with paintings. Their titles speak to medical history, to illness, to care (or the lack thereof). A small painting titled Instruction Manual for Vanishing shows a solitary, wooden chair. The chair seems to be within an empty room. It is cast in shadow, yet a fantastical, swirling, marbled pattern unfolds in front of it. Bringing to mind the ornate, marbled endpapers of antique books, it is also evocative of the psychedelic visual language of the 1960s and 70s and, indeed, the hallucinatory visions produced by taking drugs such as LSD. The title of the painting suggests the absence of a person, yet there is also something anthropomorphic about the chair, alone, isolated, the lexical relationship it has to humans – back, arms, legs. Given the context of the environment in which this painting hangs – a waiting room in a medical facility – the title also perhaps addresses the erasure of identity, of individuality, that can happen within medical settings – patients treated not as people but as objects (again, the anthropomorphic chair), ignored, not taken seriously. This is something that seems especially true for women, with various recent articles about doctors not taking pain experienced by women seriously.

The Victorians sought to “domesticate insanity”, creating facilities that were familiar and comfortable, aiming to create a sense of “homishness”,[ii] while upper-class families of the time could avoid the stigma of having a relative admitted into an asylum by keeping them at home and hidden away.[iii] The domestic is drawn out in Metcalf’s waiting room, also through the evocation of comfort and familiarity. Carpet lines the floor – a feature that is especially relevant as visitors to The Perimeter are usually expected to take off their shoes – while chairs, that could easily be envisioned around a dining room table, line the walls. The TV plays a film in which Metcalf is seen lying in bed (in a bedroom, rather than a hospital). This is interwoven with scenes of her painting and excerpts from therapy sessions, further blurring the line between the home and the institution of medicine.

![]()

![]()

From the waiting room, viewers can look into a second room through a large window set into the wall (a construction made specifically for this exhibition). Inside are five large sculptures – walking sticks looped in such a way that, from the sticks’ slender frames, a circular protrusion emerges, housing a piece of coloured glass with a tree painted on the surface. Like the chair in the painting Instruction Manual for Vanishing, the sticks are human in physicality. The titles of these sculptures suggest pregnancy (Haunted Globus/Womb #3, for example), further solidified by the image of the tree painted onto their swollen stomachs, but also hint at the idea of delusion – a phantom pregnancy. With no access to the room that these sculptures haunt, we might consider the ambiguity between care and confinement. As is suggested in Metcalf’s text for the exhibition catalogue, these sticks could be inhabiting a room, a sanctuary, a prison.[iv]

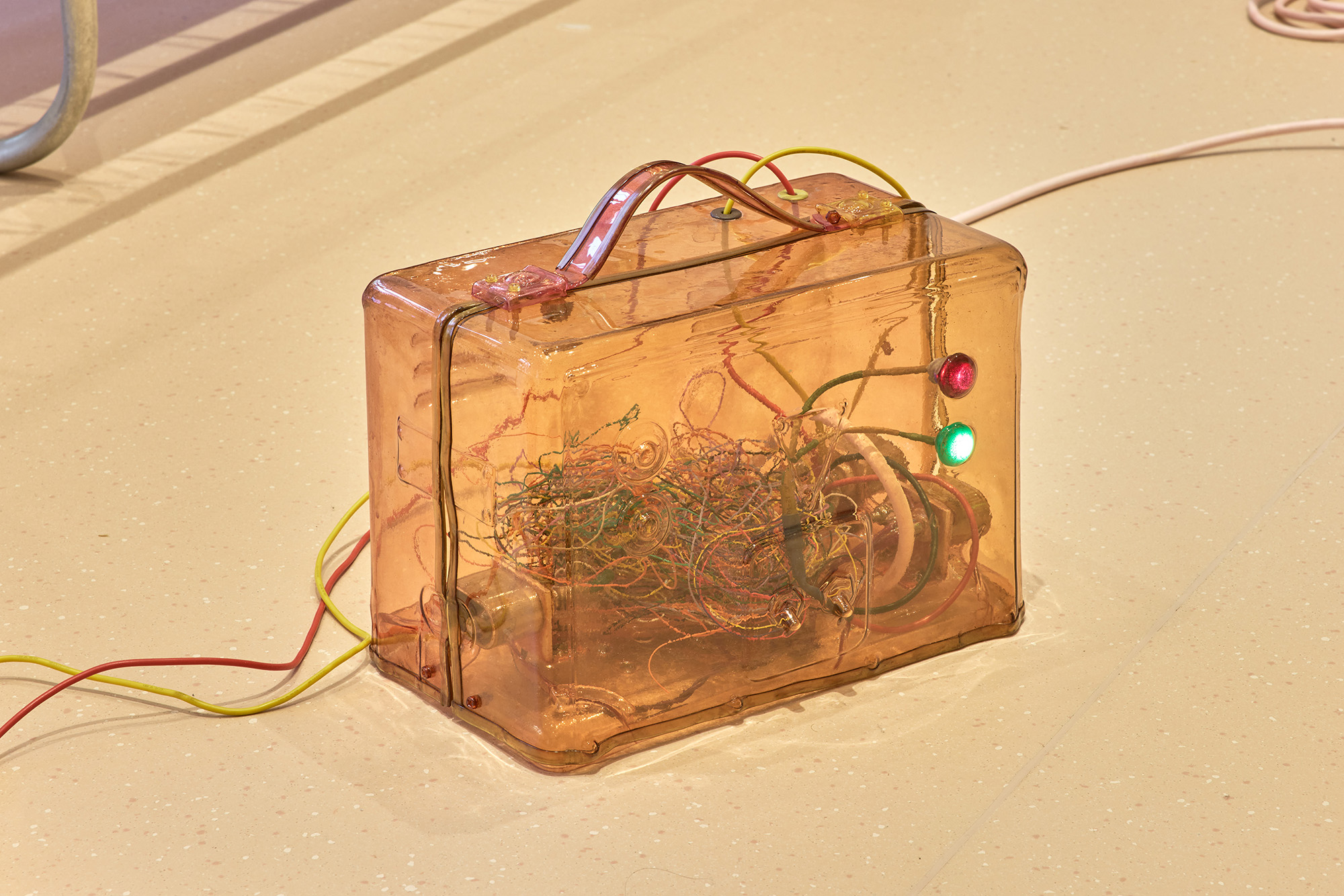

Up the large, curving staircase of the gallery, the second floor presents a hospital ward. Two hospital beds made of vintage sun loungers, with 60s floral and paisley patterns, and old leather trunks, draw our attention. A surgical light takes on the role of a patient, sitting on the edge of the bed in melancholy contemplation. On the second bed, the surgical light patient lays back, perhaps in a medically-induced state of unresponsiveness – half in, half out of the bed. With flesh-pink, speckled vinyl flooring and clinical white walls, it is easy to imagine treading this room in socks and a hospital gown, wheeling along an IV drip.

![]()

![]()

![]()

On the wall, a large oil and watercolour painting titled I AM MY OWN RIOT & BEST FRIEND. Like much of the work in this exhibition, it seems to build up a structure of fragmented memories, drawing from different time periods, incorporating into the painting Victorian lace doilies and mid-century patterns. Young women flit through this painting, sometimes smiling, sometimes faceless (again, maybe a hark back to anonymity, a loss of autonomy). A dominating figure, painted in black and white, could be taken from an old photograph. Another smiling girl brings a ghostly presence, not quite corporeally present, blending into her environment like a half-forgotten thought. These girls inhabit an environment that is collapsing. Gaping holes form in the architecture of their world, along with peeling wallpaper and shadowy presences.

The Perimeter gallery, in many ways, feels like the perfect setting for Metcalf’s installations. Renovated in 2017 by 6a architects, parts of the original fabric date back to the early 1800s. The impressive precast concrete staircase that stretches up through the heart of the building references traditional Georgian cantilever stone stairs, yet there is a feeling of domesticity brought out by the beautiful silver nickel balustrade. The arrangement of the gallery takes cues from the Sir John Soane’s Museum, while the circular skylight at the top of the building feels modern. As the architects put it, “what is old, and what is new, institutional or domestic is ambiguous”,[v] and this sentiment reflects many of the themes found in this exhibition.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

[i] Jennifer Higgie, “Alexandra

Metcalf’s ‘Gaaaaaaap’” in Alexandra Metcalf, The Scissor and Dadd (The

Perimeter, 2025), p.15.

figs.i,ii

In the first room, Metcalf recreates the waiting room of a hospital or clinic. The room invites the viewer to interact with it: to sit down on one of the upholstered wooden chairs (sourced from a church), to watch the TV perched on a high shelf in the corner of the room, to assume the role of patient. Although unspecified, we might consider this room to be the waiting room of a Victorian psychiatric facility or asylum – in the accompanying exhibition catalogue, an essay by Jennifer Higgie outlines Metcalf’s interest in the figure of “Crazy Jane”, an archetypal “mad woman” derived from Shakespeare’s Ophelia and popular during the Romantic period, and her portrait painted by Richard Dadd, the Victorian artist who was admitted to Bethlem psychiatric hospital (also known as Bedlam) after murdering his father while believing him to be an impostor. Poor Richard, locked in the asylum, so full of waiting rooms, as Higgie writes.[i]

But Metcalf is not only interested in this period of history. Through her immersive environments, she slips between time, stitching together the past and the present, familiarity and unfamiliarity, the domestic and the institutional. What results is a kind of sensory collage, an in-betweenness that leaves the viewer not quite in one place or the other. The 1960s geometric wallpaper juxtaposed with the Victorian wooden wainscoting panelling feels old-fashioned, while the 90s silver box TV has its own nostalgia. The LED ceiling panels are reminiscent of hospitals or offices – cold, unwelcoming environments that have an air of detachment. Waiting rooms, themselves, are liminal spaces, and this lends itself well to Metcalf’s playful meshing together of different eras.

figs.iii,iv

Like many waiting rooms, Metcalf’s is lined with paintings. Their titles speak to medical history, to illness, to care (or the lack thereof). A small painting titled Instruction Manual for Vanishing shows a solitary, wooden chair. The chair seems to be within an empty room. It is cast in shadow, yet a fantastical, swirling, marbled pattern unfolds in front of it. Bringing to mind the ornate, marbled endpapers of antique books, it is also evocative of the psychedelic visual language of the 1960s and 70s and, indeed, the hallucinatory visions produced by taking drugs such as LSD. The title of the painting suggests the absence of a person, yet there is also something anthropomorphic about the chair, alone, isolated, the lexical relationship it has to humans – back, arms, legs. Given the context of the environment in which this painting hangs – a waiting room in a medical facility – the title also perhaps addresses the erasure of identity, of individuality, that can happen within medical settings – patients treated not as people but as objects (again, the anthropomorphic chair), ignored, not taken seriously. This is something that seems especially true for women, with various recent articles about doctors not taking pain experienced by women seriously.

The Victorians sought to “domesticate insanity”, creating facilities that were familiar and comfortable, aiming to create a sense of “homishness”,[ii] while upper-class families of the time could avoid the stigma of having a relative admitted into an asylum by keeping them at home and hidden away.[iii] The domestic is drawn out in Metcalf’s waiting room, also through the evocation of comfort and familiarity. Carpet lines the floor – a feature that is especially relevant as visitors to The Perimeter are usually expected to take off their shoes – while chairs, that could easily be envisioned around a dining room table, line the walls. The TV plays a film in which Metcalf is seen lying in bed (in a bedroom, rather than a hospital). This is interwoven with scenes of her painting and excerpts from therapy sessions, further blurring the line between the home and the institution of medicine.

figs.v,vi

From the waiting room, viewers can look into a second room through a large window set into the wall (a construction made specifically for this exhibition). Inside are five large sculptures – walking sticks looped in such a way that, from the sticks’ slender frames, a circular protrusion emerges, housing a piece of coloured glass with a tree painted on the surface. Like the chair in the painting Instruction Manual for Vanishing, the sticks are human in physicality. The titles of these sculptures suggest pregnancy (Haunted Globus/Womb #3, for example), further solidified by the image of the tree painted onto their swollen stomachs, but also hint at the idea of delusion – a phantom pregnancy. With no access to the room that these sculptures haunt, we might consider the ambiguity between care and confinement. As is suggested in Metcalf’s text for the exhibition catalogue, these sticks could be inhabiting a room, a sanctuary, a prison.[iv]

Up the large, curving staircase of the gallery, the second floor presents a hospital ward. Two hospital beds made of vintage sun loungers, with 60s floral and paisley patterns, and old leather trunks, draw our attention. A surgical light takes on the role of a patient, sitting on the edge of the bed in melancholy contemplation. On the second bed, the surgical light patient lays back, perhaps in a medically-induced state of unresponsiveness – half in, half out of the bed. With flesh-pink, speckled vinyl flooring and clinical white walls, it is easy to imagine treading this room in socks and a hospital gown, wheeling along an IV drip.

figs.vii-ix

On the wall, a large oil and watercolour painting titled I AM MY OWN RIOT & BEST FRIEND. Like much of the work in this exhibition, it seems to build up a structure of fragmented memories, drawing from different time periods, incorporating into the painting Victorian lace doilies and mid-century patterns. Young women flit through this painting, sometimes smiling, sometimes faceless (again, maybe a hark back to anonymity, a loss of autonomy). A dominating figure, painted in black and white, could be taken from an old photograph. Another smiling girl brings a ghostly presence, not quite corporeally present, blending into her environment like a half-forgotten thought. These girls inhabit an environment that is collapsing. Gaping holes form in the architecture of their world, along with peeling wallpaper and shadowy presences.

The Perimeter gallery, in many ways, feels like the perfect setting for Metcalf’s installations. Renovated in 2017 by 6a architects, parts of the original fabric date back to the early 1800s. The impressive precast concrete staircase that stretches up through the heart of the building references traditional Georgian cantilever stone stairs, yet there is a feeling of domesticity brought out by the beautiful silver nickel balustrade. The arrangement of the gallery takes cues from the Sir John Soane’s Museum, while the circular skylight at the top of the building feels modern. As the architects put it, “what is old, and what is new, institutional or domestic is ambiguous”,[v] and this sentiment reflects many of the themes found in this exhibition.

figs.x-xiv

[i] Jennifer Higgie, “Alexandra

Metcalf’s ‘Gaaaaaaap’” in Alexandra Metcalf, The Scissor and Dadd (The

Perimeter, 2025), p.15.

[ii] Elaine Showalter, The Female

Malady: Women, Madness and English Culture, 1830–1980 (Virago, 1995), p.

28.

[iii] Ibid., p. 26.

[iv] Alexandra Metcalf, The Scissor

and Dadd (The Perimeter, 2025), p. 136

[v] 6a website, https://6a.co.uk/projects/selected/the-perimeter.

Alexandra Metcalf graduated from the Chelsea College of Art and Design, London and Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Her work has recently been exhibited at No. 9 Cork Street, London; FRAC

Corsica, Corte; Forde, Geneva; Kunsthalle Zürich; Champ Lacombe, Biarritz; 15 Orient Gallery, New York

and Ginny on Frederick, London. Metcalf’s work is held in The Museum of Modern Art Library Collection,

New York; The Perry and Marty Granoff Center for the Creative Arts, Brown University, Providence and

The Perimeter, London..

www.alexandrametcalf.com

The Perimeter is a non-profit exhibition space for contemporary art in London, founded by Alexander

V. Petalas. The exhibition programme is defined by The Perimeter’s objective to elevate British and

international contemporary artists at pivotal moments in their careers.

Since opening in 2018, The Perimeter has staged solo exhibitions dedicated to Carmen Herrera, Sarah

Lucas, Ron Nagle, Anj Smith, Anna Uddenberg and Joseph Yaeger, among others. Group exhibitions,

often in partnership with external curators and institutions, have highlighted the work of artists including

Phyllida Barlow, Anthea Hamilton, Rachel Jones, Helen Marten, Rene Matić, Walter Price, Wolfgang

Tillmans and Salman Toor.

To support the creation of new work and ambitious exhibitions, The Perimeter frequently collaborates

with international institutional partners to co-produce exhibitions and catalogues, and realise new

artwork commissions.

www.theperimeter.co.uk

Rochelle Roberts is a writer and editor based in London. Her writing has been published by Prototype, Arusha gallery, Poetry Birmingham Literary Journal, Art of Choice, and Maximillian William gallery, amongst others. Her debut pamphlet Your Retreating Shadow was published in 2022 by Broken Sleep Books and she is a contributor to the book Cusp: Feminist Writings on Bodies, Myth & Magic (Ache, 2022).

www.rocheller.weebly.com

Since opening in 2018, The Perimeter has staged solo exhibitions dedicated to Carmen Herrera, Sarah Lucas, Ron Nagle, Anj Smith, Anna Uddenberg and Joseph Yaeger, among others. Group exhibitions, often in partnership with external curators and institutions, have highlighted the work of artists including Phyllida Barlow, Anthea Hamilton, Rachel Jones, Helen Marten, Rene Matić, Walter Price, Wolfgang Tillmans and Salman Toor.

To support the creation of new work and ambitious exhibitions, The Perimeter frequently collaborates with international institutional partners to co-produce exhibitions and catalogues, and realise new artwork commissions.

www.theperimeter.co.uk