Venice Biennale 2025: part 3, the ugly

In the final part of our trio of articles originally published on our Substack at the opening week of the Venice Biennale of Architecture, we look at the Ugly.

The last two articles looked at the Good and Bad of the recently-ended 2025 Venice Biennale of Architecture. To complete the trio of pieces we originally publshed on our Substack during the opening weeks vernissage, we turn our attention to The Ugly. This is not Ugly architecture in aesthetics, but in politics, power, privilege, and ethics — and ironically it involves a designer who declares that he hates “ugly” buildings as, somehow, they are the direct opposite to “human” on a scale of his own making, Thomas Heatherwick:

No Biennale would be a Biennale without some political drama bubbling away – last year, for example, the Saudi megaproject of NEOM and The Line opened a pavilion away from the action and a day after most journalists had left the pre-presentation, arguably deliberately to avoid noise over a project that has been accused of resulting in over 21,000 deaths of migrant workers so far.

This year, the dark politics is present with the Russian Pavilion, a building on the Giardini main drag that closed in 2022 after the violent invasion of Ukraine. Owned by the Russian Federation, in 2024 it was ‘lent’ to Bolivia for in a deal understood to relate to access to up to 23 million tonnes of lithium in the South American nation.

For 2025, the Biennale organisers entered into “a collaboration agreement” with the Russian Federation gave their otherwise abandoned building to the Biennale organisers as a space “for cooperation and visibility for activities dedicated to universities, schools, families, and the general public as part of La Biennale’s Educational programme.” While a grand building, well located, it does however shout “RUSSIA” on the façade, so you might think that most educators, charities, and architects might want to stay well away for the obvious risk to public perception and reputation.

But not Heatherwick Studio, who gladly opened the Russia Pavilion space with a ‘public debate’ titled “How do we make the outside of buildings radically more human?” as part of their ongoing Humanise campaign off the back of designer Heatherwick’s book (a text described by Karrie Jacobs in recessed.space as “a relentless sales pitch” — see 00151).

![]()

figs.i-iii

We spoke to Michal Murawski, the curator of this year’s Ukraine pavilion, who expressed shock and anger, especially with the organisers of La Biennale who he suggested had betrayed the Ukrainian Pavilion team. He said: “Architecture is always about politics. Why must the Biennale be a site where the violence of the world is simply legitimated and reinforced?”

We also reached out to Heatherwick Studio for comment who said the event had to be held there “Due to the renovation of the Central Pavilion where many events would usually be held.” Venice is a city with more events and for-hire spaces than most others, and indeed the Biennale sites of Giardini and Arsenale have a wealth of other spaces, so from the outside it does seem to be a choice to accept use the Russian Pavilion, one that could have been avoided if desired.

Heatherwick Studio say that the event wasn’t held after press-preview days in order avoid critical coverage, but that it was “intended for the general public” and so occurred on the opening public day. that however did not prevent protestors, including the Ukrainian Pavilion team from raising opposition with statements and banners at the event.

“On the website of the Venice Biennale, it is written that the Venice Biennale signed a collaboration agreement with the Russian Federation, literally the Venice Biennale calls itself a collaborator with the Russian Federation!” Murawski informed the audience during the event, adding that “by being here and having this event about humanising architecture in the Russian pavilion, you are also collaborating with the Russian Federation – it’s not misinformation, it is literally written on the website.”

Heatherwick responded by saying that “in 2023, because Russia was banned, the Ukrainian government said to use the Russian Pavilion for education … there is information you don’t have.” Other than the date being slightly wrong, as Russia did not take part in Biennale from 2022, they in fact were not banned from the event but instead withdrew after the curator and artists of the 29th International Art Exhibition withdrew from the project, with one of the two artists, Alexandra Sukhareva, writing on Instagram at the time: “There is no place for art when civilians are dying under the fire of missiles, when citizens of Ukraine are hiding in shelters [and] when Russian protestors are getting silenced. As a Russian-born, I won’t be presenting my work at Venice.” The pavilion which was rejected by Russian artists, three years later has been accepted by Heatherwick Studio and Humanise.

The event was billed as a Public Debate, but in the end there was little actual genuine debate despite having a large audience of an estimated 100+ people. With little discussion amongst the panel and few questions from the floor (other than the protestor’s remonstration), it seemed in the main to be a promotional event for Heatherwick and Humanise, with the designer speaking for over 70% of the debate.

![]()

fig.iv

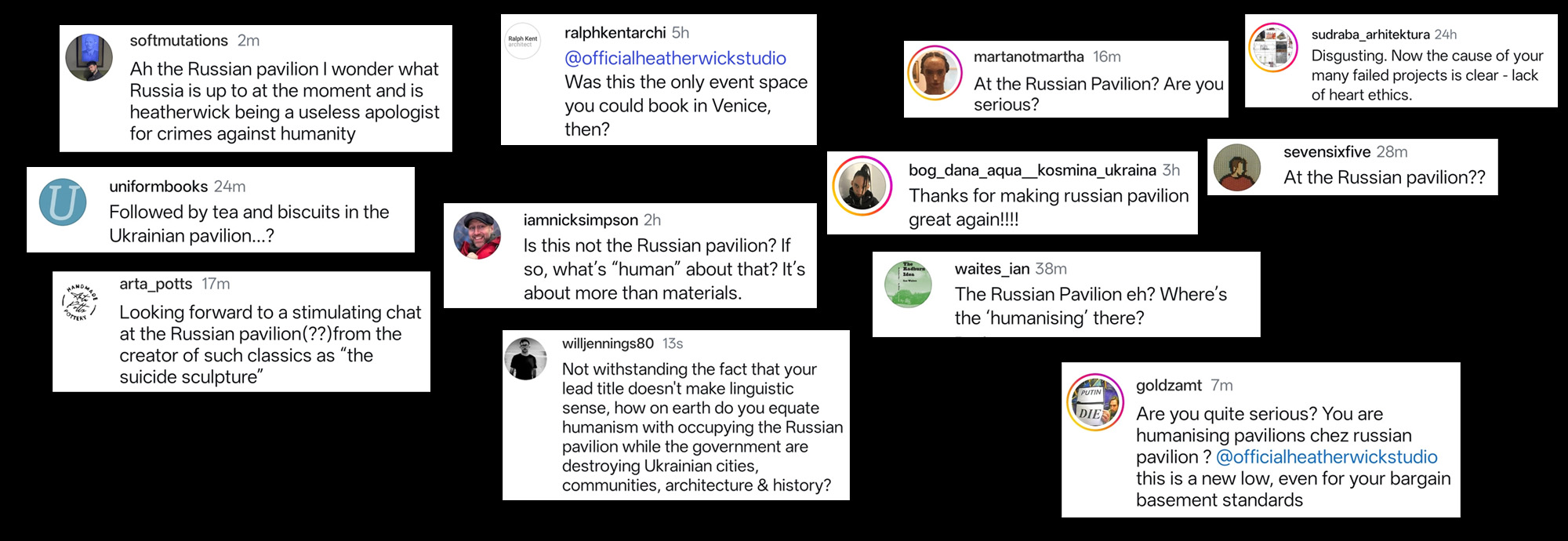

On Instagram, the conversation was also overwhelmingly one-sided, though in the counter direction. Under the announcement post from Heatherwick Studio and the Humanise campaign were a flow of comments of surprise, anger, and irony, including: “Thanks for making the Russian Pavilion great again!”, “Was this the only event space you could book?”, and “[being human] is about more than materials.”

Asked for a more general response to the wider situation at play, beyond the confines of Biennale, Heatherwick Studio responded: “In light of the invasion, we made the decision to withdraw from any projects in Russia in 2022. We stand in solidarity with everyone affected by the conflict.”

We wonder if rejecting the offer of a building directly connected to Russia for over a century, with “RUSSIA” on the façade, and owned by the Russian Federation for their use as a space of soft power, might also have been a strong, public act of solidarity, especially to Ukrainian architects, students, and citizens.

No Biennale would be a Biennale without some political drama bubbling away – last year, for example, the Saudi megaproject of NEOM and The Line opened a pavilion away from the action and a day after most journalists had left the pre-presentation, arguably deliberately to avoid noise over a project that has been accused of resulting in over 21,000 deaths of migrant workers so far.

This year, the dark politics is present with the Russian Pavilion, a building on the Giardini main drag that closed in 2022 after the violent invasion of Ukraine. Owned by the Russian Federation, in 2024 it was ‘lent’ to Bolivia for in a deal understood to relate to access to up to 23 million tonnes of lithium in the South American nation.

For 2025, the Biennale organisers entered into “a collaboration agreement” with the Russian Federation gave their otherwise abandoned building to the Biennale organisers as a space “for cooperation and visibility for activities dedicated to universities, schools, families, and the general public as part of La Biennale’s Educational programme.” While a grand building, well located, it does however shout “RUSSIA” on the façade, so you might think that most educators, charities, and architects might want to stay well away for the obvious risk to public perception and reputation.

But not Heatherwick Studio, who gladly opened the Russia Pavilion space with a ‘public debate’ titled “How do we make the outside of buildings radically more human?” as part of their ongoing Humanise campaign off the back of designer Heatherwick’s book (a text described by Karrie Jacobs in recessed.space as “a relentless sales pitch” — see 00151).

figs.i-iii

We spoke to Michal Murawski, the curator of this year’s Ukraine pavilion, who expressed shock and anger, especially with the organisers of La Biennale who he suggested had betrayed the Ukrainian Pavilion team. He said: “Architecture is always about politics. Why must the Biennale be a site where the violence of the world is simply legitimated and reinforced?”

We also reached out to Heatherwick Studio for comment who said the event had to be held there “Due to the renovation of the Central Pavilion where many events would usually be held.” Venice is a city with more events and for-hire spaces than most others, and indeed the Biennale sites of Giardini and Arsenale have a wealth of other spaces, so from the outside it does seem to be a choice to accept use the Russian Pavilion, one that could have been avoided if desired.

Heatherwick Studio say that the event wasn’t held after press-preview days in order avoid critical coverage, but that it was “intended for the general public” and so occurred on the opening public day. that however did not prevent protestors, including the Ukrainian Pavilion team from raising opposition with statements and banners at the event.

“On the website of the Venice Biennale, it is written that the Venice Biennale signed a collaboration agreement with the Russian Federation, literally the Venice Biennale calls itself a collaborator with the Russian Federation!” Murawski informed the audience during the event, adding that “by being here and having this event about humanising architecture in the Russian pavilion, you are also collaborating with the Russian Federation – it’s not misinformation, it is literally written on the website.”

Heatherwick responded by saying that “in 2023, because Russia was banned, the Ukrainian government said to use the Russian Pavilion for education … there is information you don’t have.” Other than the date being slightly wrong, as Russia did not take part in Biennale from 2022, they in fact were not banned from the event but instead withdrew after the curator and artists of the 29th International Art Exhibition withdrew from the project, with one of the two artists, Alexandra Sukhareva, writing on Instagram at the time: “There is no place for art when civilians are dying under the fire of missiles, when citizens of Ukraine are hiding in shelters [and] when Russian protestors are getting silenced. As a Russian-born, I won’t be presenting my work at Venice.” The pavilion which was rejected by Russian artists, three years later has been accepted by Heatherwick Studio and Humanise.

The event was billed as a Public Debate, but in the end there was little actual genuine debate despite having a large audience of an estimated 100+ people. With little discussion amongst the panel and few questions from the floor (other than the protestor’s remonstration), it seemed in the main to be a promotional event for Heatherwick and Humanise, with the designer speaking for over 70% of the debate.

fig.iv

On Instagram, the conversation was also overwhelmingly one-sided, though in the counter direction. Under the announcement post from Heatherwick Studio and the Humanise campaign were a flow of comments of surprise, anger, and irony, including: “Thanks for making the Russian Pavilion great again!”, “Was this the only event space you could book?”, and “[being human] is about more than materials.”

Asked for a more general response to the wider situation at play, beyond the confines of Biennale, Heatherwick Studio responded: “In light of the invasion, we made the decision to withdraw from any projects in Russia in 2022. We stand in solidarity with everyone affected by the conflict.”

We wonder if rejecting the offer of a building directly connected to Russia for over a century, with “RUSSIA” on the façade, and owned by the Russian Federation for their use as a space of soft power, might also have been a strong, public act of solidarity, especially to Ukrainian architects, students, and citizens.

Lorem Ipsum is dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. In aliquet elementum nulla, blandit tempor nunc. Phasellus ullamcorper lorem risus. Nulla in molestie dui.

www.url.com

Lorem Ipsum is dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. In aliquet elementum nulla, blandit tempor nunc. Phasellus ullamcorper lorem risus. Nulla in molestie dui.

www.url.com

Lorem Ipsum is dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. In aliquet elementum nulla, blandit tempor nunc. Phasellus ullamcorper lorem risus. Nulla in molestie dui.

www.url.com

www.url.com

Lorem Ipsum is dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. In aliquet elementum nulla, blandit tempor nunc. Phasellus ullamcorper lorem risus. Nulla in molestie dui.

www.url.com

images

fig.i Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Vivamus pulvinar risus quis feugiat commodo. Suspendisse rhoncus diam et viverra dignissim. Integer ac quam sed lectus eleifend volutpat.

fig.ii Sed consequat ante eget magna rhoncus ultricies laoreet sit amet odio. © Lorem Ipsum

images

fig.i

The Russian Pavilion. Photograph © Will Jennnings

fig.ii Event promotional image. © Heatherwick Studio & Humanise

fig.iii Image of protest at event. Photographer whishes to remain anonymous.

fig.iv Comments under the Heatherwick Studio/Humanise event announcement on Instagram

publication date

30 November 2025

tags

Thomas Heatherwick, Heatherwick Studio, Humanise, Karrie Jacobs, Michal Murawski, Politics, Russia, Ukraine, Venice, Venice Biennale

fig.ii Sed consequat ante eget magna rhoncus ultricies laoreet sit amet odio. © Lorem Ipsum