Kanal-Centre Pompidou in Brussels: a masterplan for culture

In November, Brussels opens one of the largest cultural

centres in the world. Kanal-Centre Pompidou transforms a vast former Citroën

factory into an internal landscape for culture, with a huge glass roof

punctured by three towers of galleries and infrastructure. It’s all overseen by

a trio of architects – EM2N, noArchitecten & Sergison Bates – & Will

Jennings went along to see it under construction.

The appropriation of huge post-industrial lumps of

architecture for contemporary cultural uses is nothing new. Warehouses, power

stations, factories, and brutalist sheds make almost perfect ready-mades for

art: often in the right parts of city to support the desired gentrification;

strong structural and secure bones with high ceilings and few windows; and recognisable

and powerful buildings even if not always classically beautiful.

Tate Modern was not the first, but in the quarter of a century since it opened the void of H&dM’s Turbine Hall to the public there has been a recognisable wave of industrial>cultural conversions globally, usually with a singular designer adding their recognisable flourish to the project: Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town by Heatherwick Studio, Milan’s Fondazione Prada by OMA, Kunsthalle Praha by Schindler Seko Architects (see 00240), and many, many more. In 2007, Brussels joined the club when a concrete deco brewery building was appropriated to become WIELS art gallery, but now the same city is taking the game to a whole new level – and in the process radically reimagining the trope.

![]()

![]()

In November this year, Kanal-Centre Pompidou opens its doors to the people of Brussels. The largest museum project in Europe, encompassing 40,000 square metres of a former Citroën factory, it does not follow the tried and tested patterns for post-industrial cultural occupation. Not only would the building not really allow the traditional approach, but the institutional and design teams never wanted to recreate what had gone before.

“We wanted to tread the line between being a building and part of the city,” said Yves Goldstein, the Director-General of the organisation, who has spent nearly a decade seeing this project grow from kernel of an idea to the bustling building site it is when recessed.space visited. He is not quite there yet – there is still a lot to do before the opening ten exhibitions and on a tour around the site it seems that nine months may look a little optimistic.

Piles of construction equipment and materials fill the enormous site: there are gaps in the roof still awaiting glazing; welders erupt in brightness in dark shadows; kilometres of cabling track the structure; huge pipework ventilates closed-off spaces where dirty works are still taking place; scaffolding, Heras fencing, containers, Portaloos, and piles of materials make the entire place seem like a salvage yard; and amongst it all, cherry pickers dance. This does not look like an art gallery.

![]()

![]()

![]()

All this activity and use of space, however, speaks to the unique approach of this building both in construction and eventual use. Most construction sites would pile all their goods and materials off site, or in an adjoining yard, to compartmentalise the ingredients and outcome of construction. The vast internal spaces of Kanal allowed all these construction activities to happen inside, which means far more is complete than seems at first glance – and once all the detritus is whisked away, an arts centre will become legible. Perhaps they may make that hard colmpletion deadline.

Framed by two intersecting avenues that meet at a crossroads, across two levels there are large open spaces that make spaces of the Turbine Hall or Pirelli HangarBicocca (see 00105) seem small. The plan is not to fill these spaces up, but leave them as semi-public, open voids, for the city to occupy. It is an approach best seen at the Cent Quatre cultural centre in the 19th arrondissement of Paris, a former train shed turned by Atelier Novembre architects into a community space, but importantly leaving the central atrium free of programme and free to be occupied. That space is a hive of activity: people meeting, circus performers practicing, dance groups rehearsing, footballers practicing flicks, other sitting reading or revising alone. It is a genuinely generous place which is offered up to locals to use as they wish, and it has been seized with spirit.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Goldstein wants Kanal-Centre Pompidou to be seized in a similar way. Following a competition, a team of architects comprising EM2N, noArchitecten, and Sergison Bates were selected in part because they proposed simply stripping back and leaving most of the 1930s car factory empty, as a free open space to be used in unknown, unexpected civic ways.

There still is a lot of architecture though. Once open, the building will contain a new outpost of the Centre Pompidou, the city’s architecture museum and library, a new museum of modern and contemporary art, an array of workshops, a cinema, auditoriums, restaurants and countless other spaces including the vast back of house and offices required by an institution. There’s even going to be a bakery, community printers and an Assemble-designed playground.

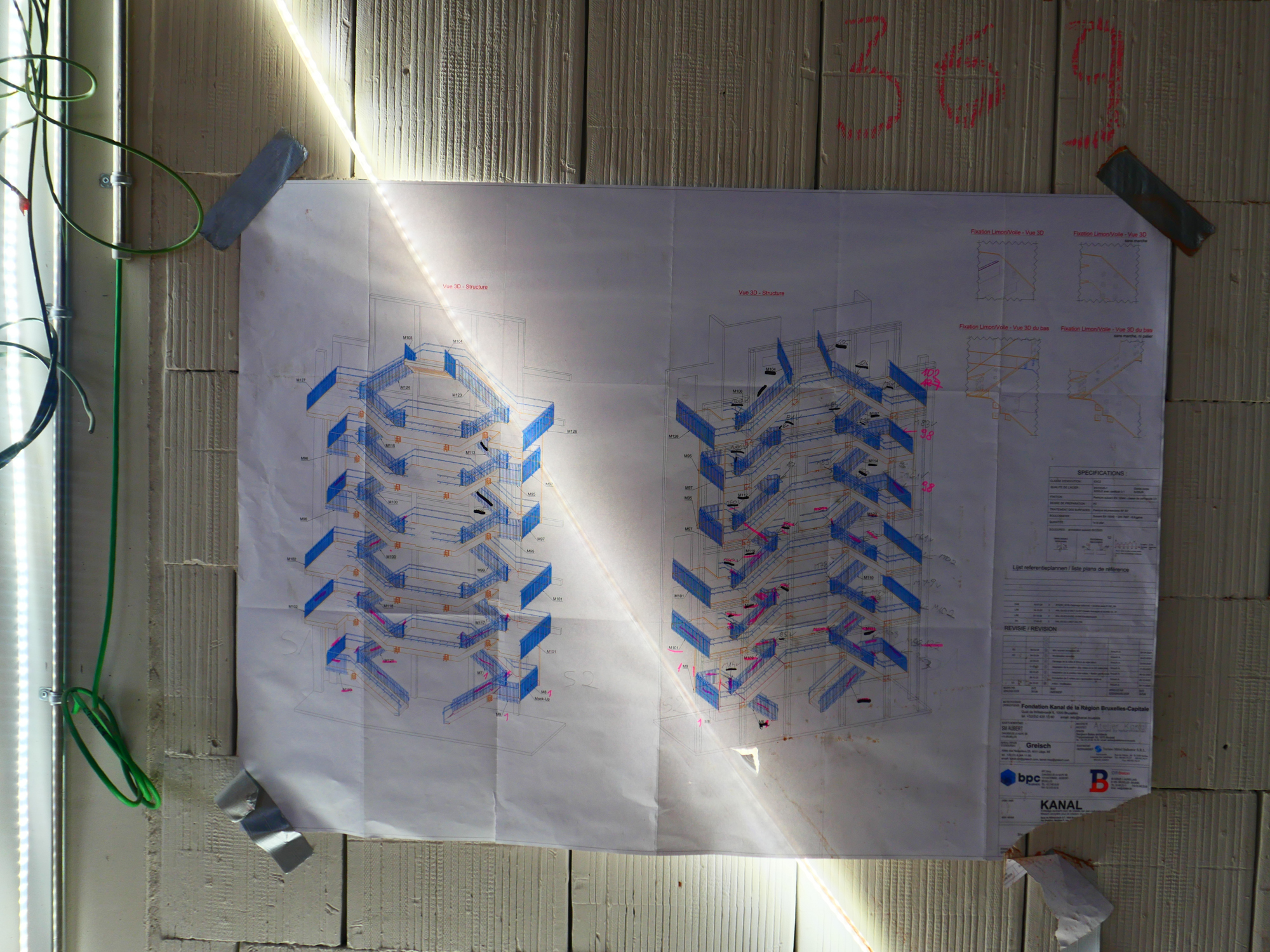

It seems as if the team of architects – who rebranded as the collective Atelier Kanal rather than use their normal practice titles – treated this more of an urban masterplan than an architectural project, treating the 100x200m more as a landscape than building. They have still provided all the required bits of new building needed, largely contained within three towers that puncture the glass roof, containing the climate-controlled and programmed uses, but most of the internal terrain seems to be left as fallow, a kind of post-industrial commons.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Some modern museums are so tightly designed, so detailed and meticulously formed, that there is little space left over for unplanned or as-yet-unknown cultural uses. Curators, artists, and visitors all enjoy the possibilities of accidental spaces, niches, corners, shadows, and other spatial characteristics that seem difficult to build into a singular cohesive design, but more emerge from piecemeal growth of place (Tate Modern’s Tanks spaces are an exception here – discovered during construction then incorporated into the design, these found forms have now become the institution’s most exciting and interesting gallery spaces). Kanal seems like it will be only be formed of such incidental and poetic spaces, whether they be the long ramps that until 2017 allowed Citroën cars to follow a Fordian path, shadowy undercrofts, vast open concrete plazas, or connecting pathways. This will be a building that artists, curators, and visitors will have fun with, through the complete lack of following contemporary gallery orthodoxy.

In 2018, after the factory closed but before architects had been appointed, the building was opened for a year of community-led activation, Kanal Brut. Not only did this let the surrounding public into a building that they had spent their life navigating around, it allowed the institution to see how people occupied the place, what culture emerged from what corners, what could be left, what was redundant, what inspired, and what was obstruction. It informed more than the spatial approach, but also the intent of horizontality, participation, and open expansiveness.

Stephen Bates – one half of the directors of Sergison Bates, and one seventh of the combined directors making up the ‘shared-authorship’ firm of Atelier Kanal – uses architectural language to describe the spatial approach. The large avenue is a “nave”, the open first floor is “the Piano Nobile”, the three roof-bursting blocks are “houses”, the largest open space is termed “the Stage of Brussels”, and whole conceptual approach is referred to as “A Third Place”, following Ray Oldenburg’s research into spaces where people linger and be, between first and second places of home and work.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The visiting international tourist will arrive through the grand cathedral-like steel and glass deco ‘front’ of the complex. The 21-metre-tall landmark showroom was where cars produced in the factory – designed by Alexis Dumont, Marcel Van Goethem and Maurice-Jacques Ravaze – ended up, shining in daylight flooding through a grid of glazing, asking to be purchased and driven into the city.

In its new life, this space will be a grand, welcoming atrium, a space for congregating, welcoming, largescale artistic intervention. A restaurant and viewing gallery overlook, an auditorium sits to the side, on the roof is a vast new public terrace and bar. It is a space that will offer Instagram moments from inside and out, become the signature of the place, and offer the sense of arrival for tourists and travellers.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

But there are other entrances around the city block, and these are more important for the way Kanal integrates into the city, and the way local citizens integrate the place into their daily lives. Three smaller entrances sit at the ends of the axis of avenues, opening at a more domestic scale, and presenting onto different urban situations. Goldstein states that fewer than 10% of Brussels residents visit a museum or cultural centre each year, and if Kanal is going to seriously help to inflate that then these entrances are arguably more important than the showroom space. It is through these ‘side doors’ that people will come through to occupy the place as Parisians have Cent Quatre, with the sense of simply using it as part of their city, not as as a visitor stepping into private space.

In nine months, Kanal will open, but this is where the hard work starts. It is one thing creating the concept and spatial forms of an open institution, but another thing to organise, manage, and programme one. It would be easy for barriers to form, for the idea of flexibility to slowly disappear as complications from project management, ticketing, exhibition curation, and spatial security demand barriers, thresholds, and control. Locals may look back fondly at the year of Kanal Brut and think the new institution will carry that anarchic spirit and sense of raw industrial occupation, and feel that the final Atelier Kanal project has ripped out the grit and magic that such abandoned spaces can conjure. It would be easy for it to become a bastion of gentrification, projecting across the canal into socially diverse neighbouring Molenbeek-Saint-Jean district as an iconic symbol of international tourism, cultural wealth, and investment in baubles.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

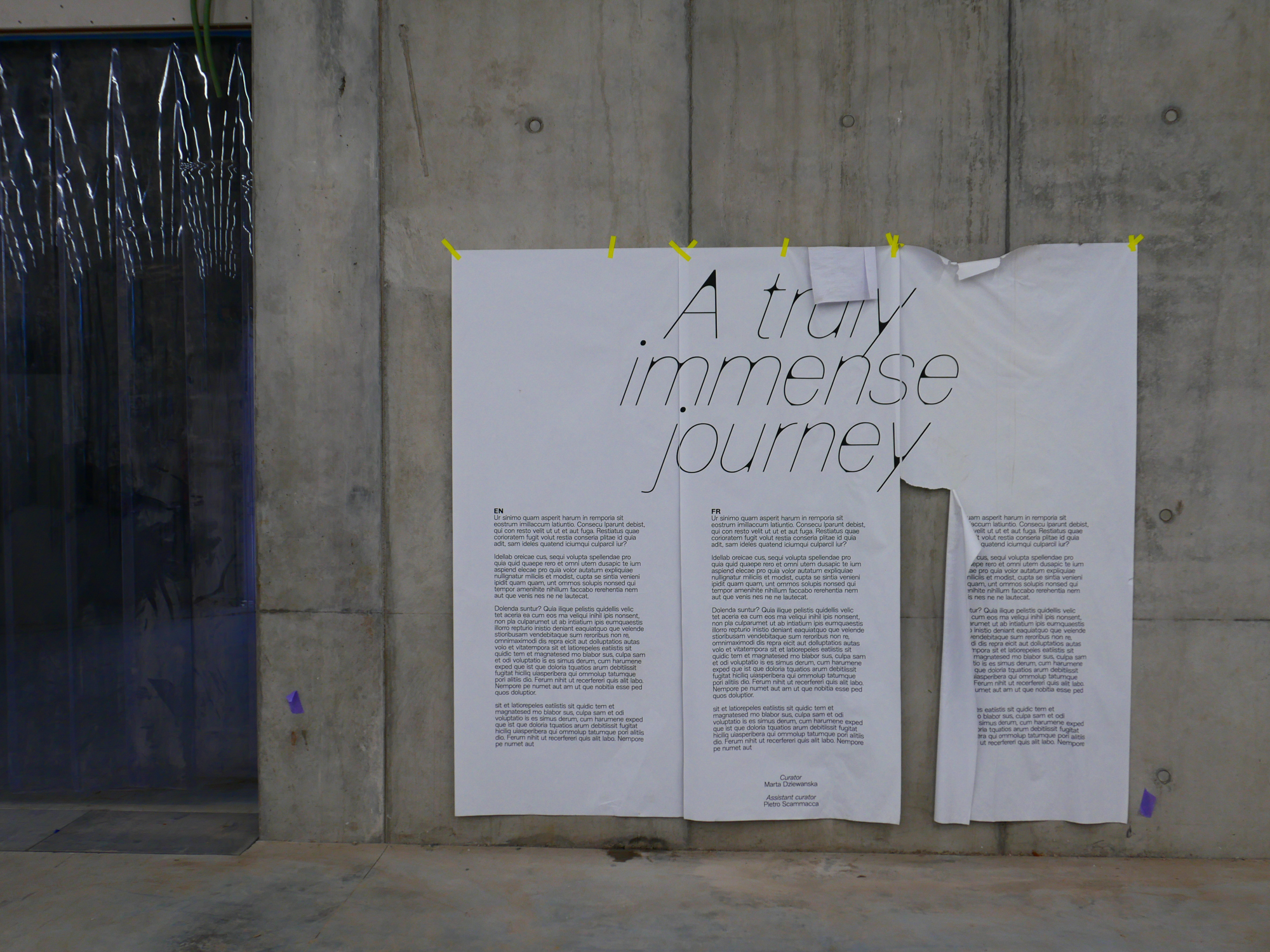

Some of the opening events speak to the organisational intent to prevent Kanal landing this way. Yes, there are the landmark and global-headline grabbing exhibitions: A Truly Immense Journey, led by partner venue Centre Pompidou, brings over 350 works by the likes of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Sonia Delaunay, and Wifredo Lam into a study of the movement and circulation of culture and people beyond Belgium; Banu Cennetoğlu presents the opening work in the former showroom, her project right? carrying a critique of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights though slowly deflating letter balloons; and An Infinite Woman: Black Archives in Two Acts, explores the image of black women in art, as colonial symbol and more recent reclamation.

But there is much more besides, and much more deeply rooted in a genuine idea of public and people. Otobong Nkanga is turning a large open space into a landscape of wooden looms, allowing mass participation to create an eventual work weaving not only threads but stories and sharing that emerge through the process – a feminist, decolonised act, reclaiming the idea of work in the former-factory. Kanal Architecture (formerly CIVA) presents Right to the City – Right to the Future, riffing off 1968’s global urban ambitions to consider a transversal approach to architecture that marries the work of building and landscape practitioners with the work of citizens, civic engagement, and associations. WERKER Collective will operate a cooperative print room as a space of communal creativity, collective authorship, and gathering space. There is space for community radio, partnerships with existing arts and community festivals, a series of film clubs with alternative and political programming, and a huge schools programme that is looking to bring 3,000 children to after-school clubs, projects to remedy digital exclusion, and empowering learning through arts.

![]()

![]()

![]()

This is all hugely ambitions, and it will be no easy balancing act for the institution to present world-leading exhibitions that require years of advance planning and experimental, pop-up, weird, provocative projects in the same space. But that is the plan, and if anywhere can contain such multifarious cultural uses – the ones we already know about and the ones that haven’t even been created yet – then the weird, sprawling, post-industrial landscape of Kanal-Centre Pompidou might be the place where it happens.

Tate Modern was not the first, but in the quarter of a century since it opened the void of H&dM’s Turbine Hall to the public there has been a recognisable wave of industrial>cultural conversions globally, usually with a singular designer adding their recognisable flourish to the project: Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town by Heatherwick Studio, Milan’s Fondazione Prada by OMA, Kunsthalle Praha by Schindler Seko Architects (see 00240), and many, many more. In 2007, Brussels joined the club when a concrete deco brewery building was appropriated to become WIELS art gallery, but now the same city is taking the game to a whole new level – and in the process radically reimagining the trope.

figs.i,ii

In November this year, Kanal-Centre Pompidou opens its doors to the people of Brussels. The largest museum project in Europe, encompassing 40,000 square metres of a former Citroën factory, it does not follow the tried and tested patterns for post-industrial cultural occupation. Not only would the building not really allow the traditional approach, but the institutional and design teams never wanted to recreate what had gone before.

“We wanted to tread the line between being a building and part of the city,” said Yves Goldstein, the Director-General of the organisation, who has spent nearly a decade seeing this project grow from kernel of an idea to the bustling building site it is when recessed.space visited. He is not quite there yet – there is still a lot to do before the opening ten exhibitions and on a tour around the site it seems that nine months may look a little optimistic.

Piles of construction equipment and materials fill the enormous site: there are gaps in the roof still awaiting glazing; welders erupt in brightness in dark shadows; kilometres of cabling track the structure; huge pipework ventilates closed-off spaces where dirty works are still taking place; scaffolding, Heras fencing, containers, Portaloos, and piles of materials make the entire place seem like a salvage yard; and amongst it all, cherry pickers dance. This does not look like an art gallery.

figs.iii-v

All this activity and use of space, however, speaks to the unique approach of this building both in construction and eventual use. Most construction sites would pile all their goods and materials off site, or in an adjoining yard, to compartmentalise the ingredients and outcome of construction. The vast internal spaces of Kanal allowed all these construction activities to happen inside, which means far more is complete than seems at first glance – and once all the detritus is whisked away, an arts centre will become legible. Perhaps they may make that hard colmpletion deadline.

Framed by two intersecting avenues that meet at a crossroads, across two levels there are large open spaces that make spaces of the Turbine Hall or Pirelli HangarBicocca (see 00105) seem small. The plan is not to fill these spaces up, but leave them as semi-public, open voids, for the city to occupy. It is an approach best seen at the Cent Quatre cultural centre in the 19th arrondissement of Paris, a former train shed turned by Atelier Novembre architects into a community space, but importantly leaving the central atrium free of programme and free to be occupied. That space is a hive of activity: people meeting, circus performers practicing, dance groups rehearsing, footballers practicing flicks, other sitting reading or revising alone. It is a genuinely generous place which is offered up to locals to use as they wish, and it has been seized with spirit.

figs.vi-viii

Goldstein wants Kanal-Centre Pompidou to be seized in a similar way. Following a competition, a team of architects comprising EM2N, noArchitecten, and Sergison Bates were selected in part because they proposed simply stripping back and leaving most of the 1930s car factory empty, as a free open space to be used in unknown, unexpected civic ways.

There still is a lot of architecture though. Once open, the building will contain a new outpost of the Centre Pompidou, the city’s architecture museum and library, a new museum of modern and contemporary art, an array of workshops, a cinema, auditoriums, restaurants and countless other spaces including the vast back of house and offices required by an institution. There’s even going to be a bakery, community printers and an Assemble-designed playground.

It seems as if the team of architects – who rebranded as the collective Atelier Kanal rather than use their normal practice titles – treated this more of an urban masterplan than an architectural project, treating the 100x200m more as a landscape than building. They have still provided all the required bits of new building needed, largely contained within three towers that puncture the glass roof, containing the climate-controlled and programmed uses, but most of the internal terrain seems to be left as fallow, a kind of post-industrial commons.

figs.ix-xi

Some modern museums are so tightly designed, so detailed and meticulously formed, that there is little space left over for unplanned or as-yet-unknown cultural uses. Curators, artists, and visitors all enjoy the possibilities of accidental spaces, niches, corners, shadows, and other spatial characteristics that seem difficult to build into a singular cohesive design, but more emerge from piecemeal growth of place (Tate Modern’s Tanks spaces are an exception here – discovered during construction then incorporated into the design, these found forms have now become the institution’s most exciting and interesting gallery spaces). Kanal seems like it will be only be formed of such incidental and poetic spaces, whether they be the long ramps that until 2017 allowed Citroën cars to follow a Fordian path, shadowy undercrofts, vast open concrete plazas, or connecting pathways. This will be a building that artists, curators, and visitors will have fun with, through the complete lack of following contemporary gallery orthodoxy.

In 2018, after the factory closed but before architects had been appointed, the building was opened for a year of community-led activation, Kanal Brut. Not only did this let the surrounding public into a building that they had spent their life navigating around, it allowed the institution to see how people occupied the place, what culture emerged from what corners, what could be left, what was redundant, what inspired, and what was obstruction. It informed more than the spatial approach, but also the intent of horizontality, participation, and open expansiveness.

Stephen Bates – one half of the directors of Sergison Bates, and one seventh of the combined directors making up the ‘shared-authorship’ firm of Atelier Kanal – uses architectural language to describe the spatial approach. The large avenue is a “nave”, the open first floor is “the Piano Nobile”, the three roof-bursting blocks are “houses”, the largest open space is termed “the Stage of Brussels”, and whole conceptual approach is referred to as “A Third Place”, following Ray Oldenburg’s research into spaces where people linger and be, between first and second places of home and work.

figs.xii-xiv

The visiting international tourist will arrive through the grand cathedral-like steel and glass deco ‘front’ of the complex. The 21-metre-tall landmark showroom was where cars produced in the factory – designed by Alexis Dumont, Marcel Van Goethem and Maurice-Jacques Ravaze – ended up, shining in daylight flooding through a grid of glazing, asking to be purchased and driven into the city.

In its new life, this space will be a grand, welcoming atrium, a space for congregating, welcoming, largescale artistic intervention. A restaurant and viewing gallery overlook, an auditorium sits to the side, on the roof is a vast new public terrace and bar. It is a space that will offer Instagram moments from inside and out, become the signature of the place, and offer the sense of arrival for tourists and travellers.

figs.xv-xviii

But there are other entrances around the city block, and these are more important for the way Kanal integrates into the city, and the way local citizens integrate the place into their daily lives. Three smaller entrances sit at the ends of the axis of avenues, opening at a more domestic scale, and presenting onto different urban situations. Goldstein states that fewer than 10% of Brussels residents visit a museum or cultural centre each year, and if Kanal is going to seriously help to inflate that then these entrances are arguably more important than the showroom space. It is through these ‘side doors’ that people will come through to occupy the place as Parisians have Cent Quatre, with the sense of simply using it as part of their city, not as as a visitor stepping into private space.

In nine months, Kanal will open, but this is where the hard work starts. It is one thing creating the concept and spatial forms of an open institution, but another thing to organise, manage, and programme one. It would be easy for barriers to form, for the idea of flexibility to slowly disappear as complications from project management, ticketing, exhibition curation, and spatial security demand barriers, thresholds, and control. Locals may look back fondly at the year of Kanal Brut and think the new institution will carry that anarchic spirit and sense of raw industrial occupation, and feel that the final Atelier Kanal project has ripped out the grit and magic that such abandoned spaces can conjure. It would be easy for it to become a bastion of gentrification, projecting across the canal into socially diverse neighbouring Molenbeek-Saint-Jean district as an iconic symbol of international tourism, cultural wealth, and investment in baubles.

figs.xix-xxii

Some of the opening events speak to the organisational intent to prevent Kanal landing this way. Yes, there are the landmark and global-headline grabbing exhibitions: A Truly Immense Journey, led by partner venue Centre Pompidou, brings over 350 works by the likes of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Sonia Delaunay, and Wifredo Lam into a study of the movement and circulation of culture and people beyond Belgium; Banu Cennetoğlu presents the opening work in the former showroom, her project right? carrying a critique of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights though slowly deflating letter balloons; and An Infinite Woman: Black Archives in Two Acts, explores the image of black women in art, as colonial symbol and more recent reclamation.

But there is much more besides, and much more deeply rooted in a genuine idea of public and people. Otobong Nkanga is turning a large open space into a landscape of wooden looms, allowing mass participation to create an eventual work weaving not only threads but stories and sharing that emerge through the process – a feminist, decolonised act, reclaiming the idea of work in the former-factory. Kanal Architecture (formerly CIVA) presents Right to the City – Right to the Future, riffing off 1968’s global urban ambitions to consider a transversal approach to architecture that marries the work of building and landscape practitioners with the work of citizens, civic engagement, and associations. WERKER Collective will operate a cooperative print room as a space of communal creativity, collective authorship, and gathering space. There is space for community radio, partnerships with existing arts and community festivals, a series of film clubs with alternative and political programming, and a huge schools programme that is looking to bring 3,000 children to after-school clubs, projects to remedy digital exclusion, and empowering learning through arts.

figs.xxiii-xxv

This is all hugely ambitions, and it will be no easy balancing act for the institution to present world-leading exhibitions that require years of advance planning and experimental, pop-up, weird, provocative projects in the same space. But that is the plan, and if anywhere can contain such multifarious cultural uses – the ones we already know about and the ones that haven’t even been created yet – then the weird, sprawling, post-industrial landscape of Kanal-Centre Pompidou might be the place where it happens.

Kanal is a museum of modern and contemporary art, architecture and landscape architecture, established and funded by the Brussels-Capital Region since 2017. Located in the former Citroën garage by the canal, just a short walk away from the historic centre, it is a meeting place that brings together artists, creators, architects and audiences.

Through a rich exhibition programme developed with diverse cultural and artistic partners and via its singular collection, Kanal showcases both established and emerging artists.

The strategic partnership with the Centre Pompidou provides Kanal with sustained access to one of the leading collections of modern and contemporary art. Works from the Centre Pompidou collection are presented in Brussels as an integral part of the artistic offer, with many pieces being shown in the city for the very first time. In parallel, Kanal Architecture's collections and programming spark reflection and debate on architecture, landscape and ecosystems that shape the city and society.

But Kanal is more than a museum. It is an extension of the city where artistic disciplines combine and converge. With ample room for performance, dance, music and film, but also freely accessible spaces to read, learn and create. With a library and archives, auditoriums and its very own print shop. With a brasserie, restaurant, bakery and rooftop bar. As a museum forever in the making, Kanal wants to engage with its visitors and start a conversation. A place for everyone to simply come by and celebrate art together, façon Kanal.

www.kanal.brussels

Atelier Kanal is the design team behind Kanal-Centre Pompidou. It comprises noAarchitecten, EM2N & Sergison Bates architects.

www.atelierkanal.cargo.site

www.noaarchitecten.net

www.em2n.ch

www.sergisonbates.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist & educator interested in cities, architecture & culture. He has written for Wallpaper*, Canvas, The Architect’s Newspaper, RIBA Journal, Icon, Art Monthly & more. He teaches history & theory at UCL Bartlett, is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios & is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics.

www.willjennings.info

www.atelierkanal.cargo.site

www.noaarchitecten.net

www.em2n.ch

www.sergisonbates.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist & educator interested in cities, architecture & culture. He has written for Wallpaper*, Canvas, The Architect’s Newspaper, RIBA Journal, Icon, Art Monthly & more. He teaches history & theory at UCL Bartlett, is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios & is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics.

www.willjennings.info