Cities & sculpture: An interview with Ai Weiwei

In an exhibition at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, Chinese artist Ai Weiwei explores the ideas of value, fakery, and doubt. Included in the exhibition is a new film Cockroach, following Hong Kong pro-democracy protesters of 2019 through the city, with both cities and politics folding into this interview with Will Jennings.

The oak floorboard creeks my arrival and Ai Weiwei,

comfortably reclined in an armchair looked up. He is in the living room of

Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, a house made for comfort and ease, in which light and

space are as central architectural components as the fabric of the building.

Originally home of Jim and Hellen Ede (Jim had been a Tate curator over the 1920s and 30s), it is formed of four interconnected cottages as a space to not only live but also carefully display their collection of 20th century art and ceramics. Kettle’s Yard is a place rooted in creativity, looking, and slow contemplation, and Weiwei seemed quite at home, settled. I asked if it was a place he was familiar with.

“I have been here many, many times. I feel so familiar to the environment and I feel comfortable, and it feels real, natural. I like it because I feel I belong to it, you know. [Jim Ede] understood how to make his life as art, make art as his life. So, I very much identify to the environment.”

Winter sun floods the window, caressing stones on the sill and rippling the silent floorboards, I wondered if it was something about the surfaces and famed light of the house, how the materials carry a patina of age and aesthetic. “No, it's not nothing about that. It’s about the ordinary feeling of how you can imagine what kind of life used to be in here. So, it’s more information than just space or material. It's a total information,” he laughed.

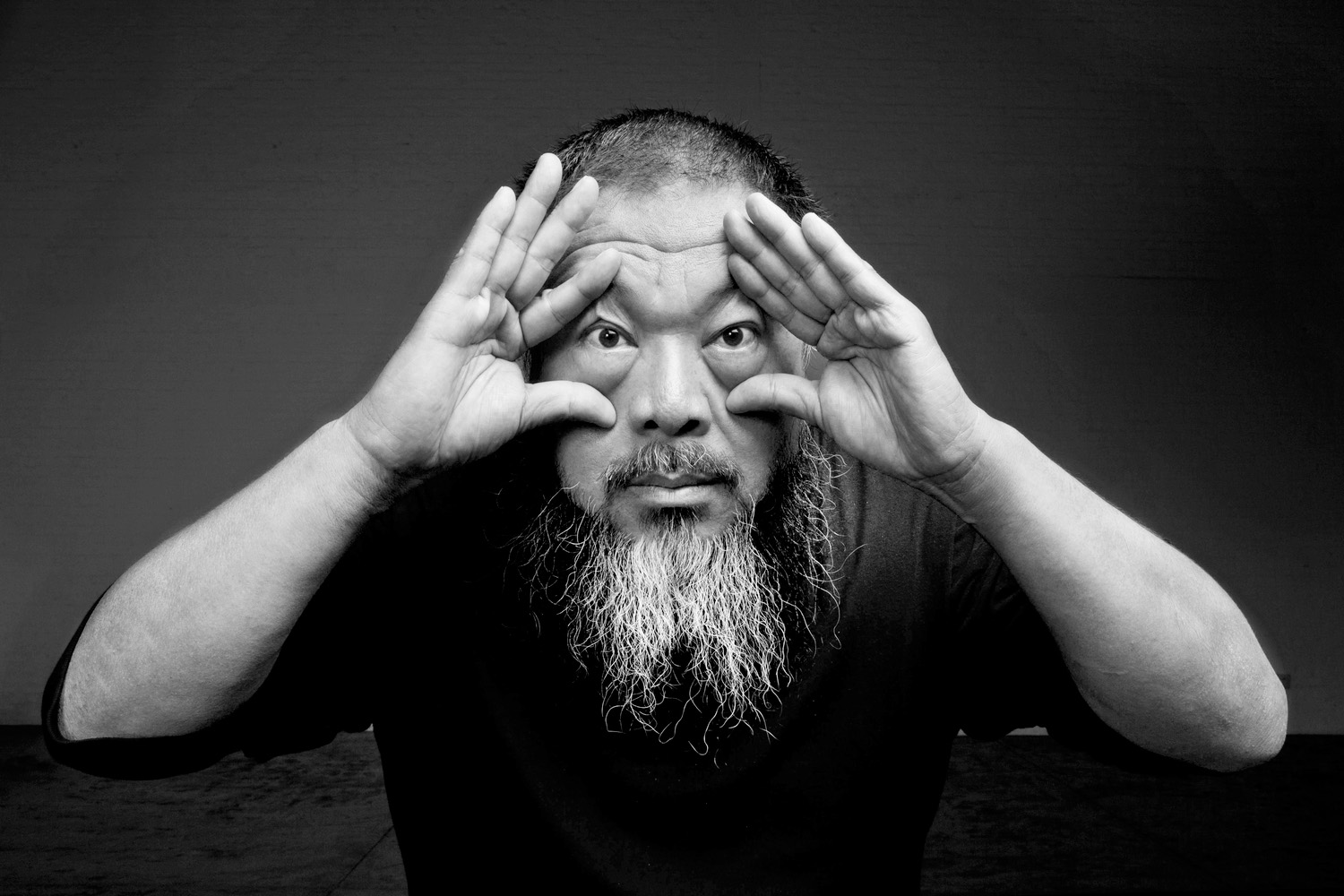

![]()

Weiwei may look settled and at home, but it’s a relationship to the domestic which he admits isn’t natural to him. His father, Ai Qing, was also an artist, a poet exiled by the government to Xinjiang in the northwest of China, a landscape of deserts and mountains, suffering a relentless punishment of harsh manual labour. In his blog, which ran for three years from 2006 until the Chinese state shut it down, Weiwei spoke about the domestic space of his childhood:

“My earliest experience with architecture was when I was eight years old, and we were sent down to Xinjiang; as punishment we were forced to live in an earthen pit. I think that in political circumstances like those, living underground can provide an incredible feeling of security - it was a pit dug right into the ground, in the winter it was warm, and in the summer it was cool. Its walls were linked with America, and its roof and floor were flush, and often enough, when pigs would run overhead, their bottoms would fall through our roof, making us too familiar with the sight of swine nether regions.”[1]

His father was too tall for the subterranean space, and so they dug the house deeper to give more headroom – an approach to dealing with architecture, material, and space from a place of simplicity and need - qualities he has taken not only into sculptural works but also architectural projects through his studio, FAKE Design.

Weiwei now lives across Europe, with his main studio in Berlin and primary residence in Portugal. He does, however, have a property in Cambridge after moving to the city in 2019, though says “I cannot call [Cambridge] my home-town, but my residence.” The word home is one he doesn’t quite recognise, adding, “I never had that privilege because I always see myself as a traveller. Every space to me is just the place to prepare me for the next trip.”

This precarious relationship to settling is perhaps contained in both his childhood displacement as well as the constant sense of being followed by the Chinese government. Instead, his rootedness is in creative making, as his father’s was before, something he has written about but still finds hard to speak of - “The story is too dramatic to tell. But all my understanding of art has come from him.”

Creativity comes from a place of need, especially within a climate when an ability to question and propose can be crushed. “What is imagination?” he wonders, “It’s got to be some kind of desire, and it's always about something we don't have. Or it's thinking what would be a good idea if it can exist.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

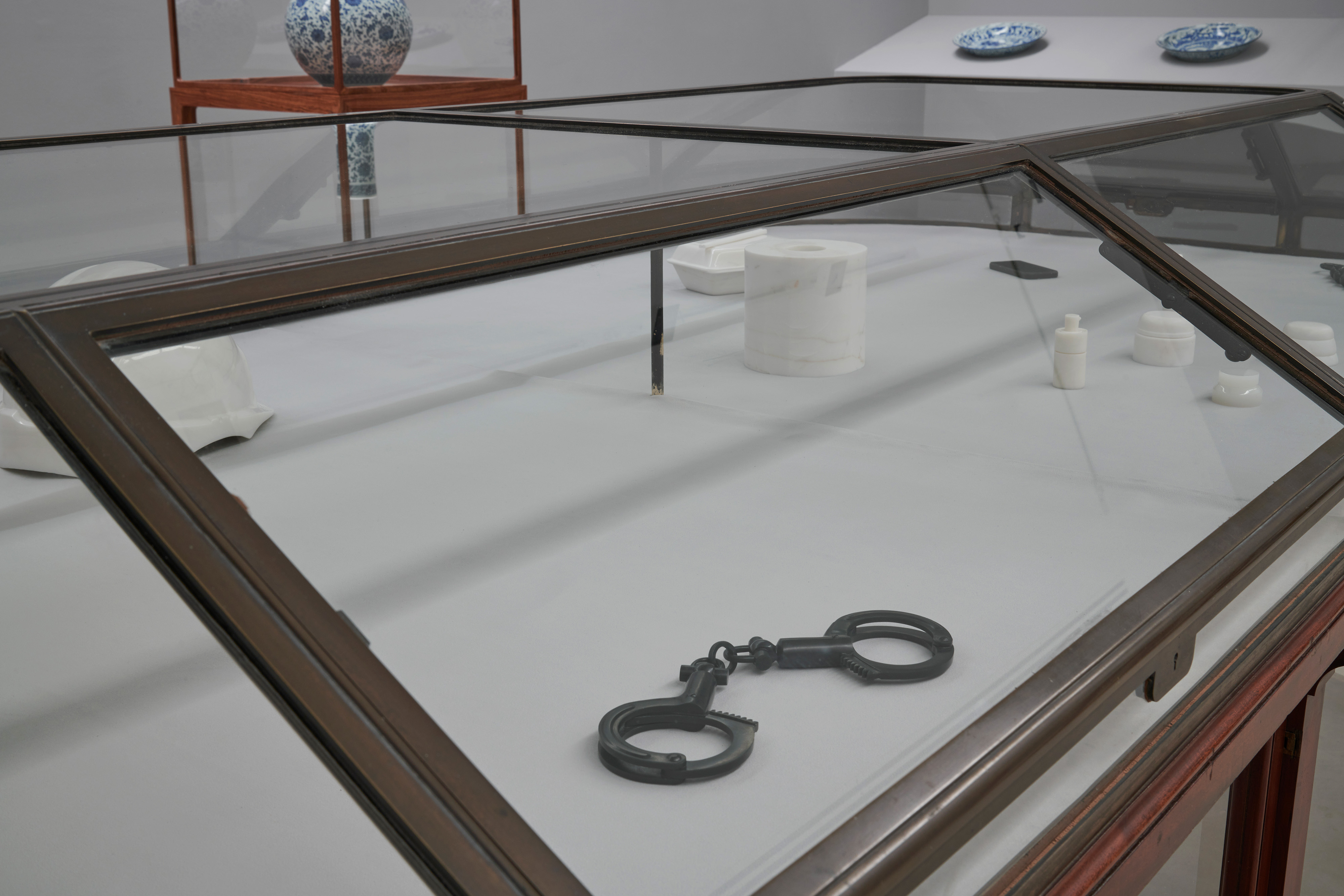

Scattered around Kettle’s Yard are works by Brancusi, Nicholson, Hepworth, Miró, and Hamilton Finlay amongst many more. Downstairs, in the new Jamie Fobert Architects’ designed gallery, they are joined by Weiwei’s exhibition The Liberty of Doubt, a collection of existing small works exploring value and meaning, alongside a second room with a grid of vitrines of Chinese antiquities bought at a Cambridge. He later discovered a number were fakes, though a typical visitor wouldn’t know which ones were authentic historical objects and which date to the last few decades - it was only through antique expert acquaintances in New York and China that the artist himself was sure which were real and which were fake.

Of course, they are all real, and this is at the heart of Weiwei’s provocation, that even fakes are legitimate art objects with a level of craftsmanship and material knowledge which should be respected and are worthy of exhibition. I thought of these objects when Weiwei made that quip about total information, and how to look beyond knowing something as a binary within a single frame but consider a material or object beyond surface. It touches on value systems and imbued power, as well as social or cultural narratives contained within its history.

Much of Weiwei’s sculptural works are carved from jade, a material he says has “the longest history in human’s fascination with objects”, and a mineral used in Chinese craft for 6,000 years as, he explains, “a tradition which has never stopped, not interrupted by war, or different kinds of religion … an ordinary piece of stone picked up from a river or a mountain range, then given such power by carving it.”

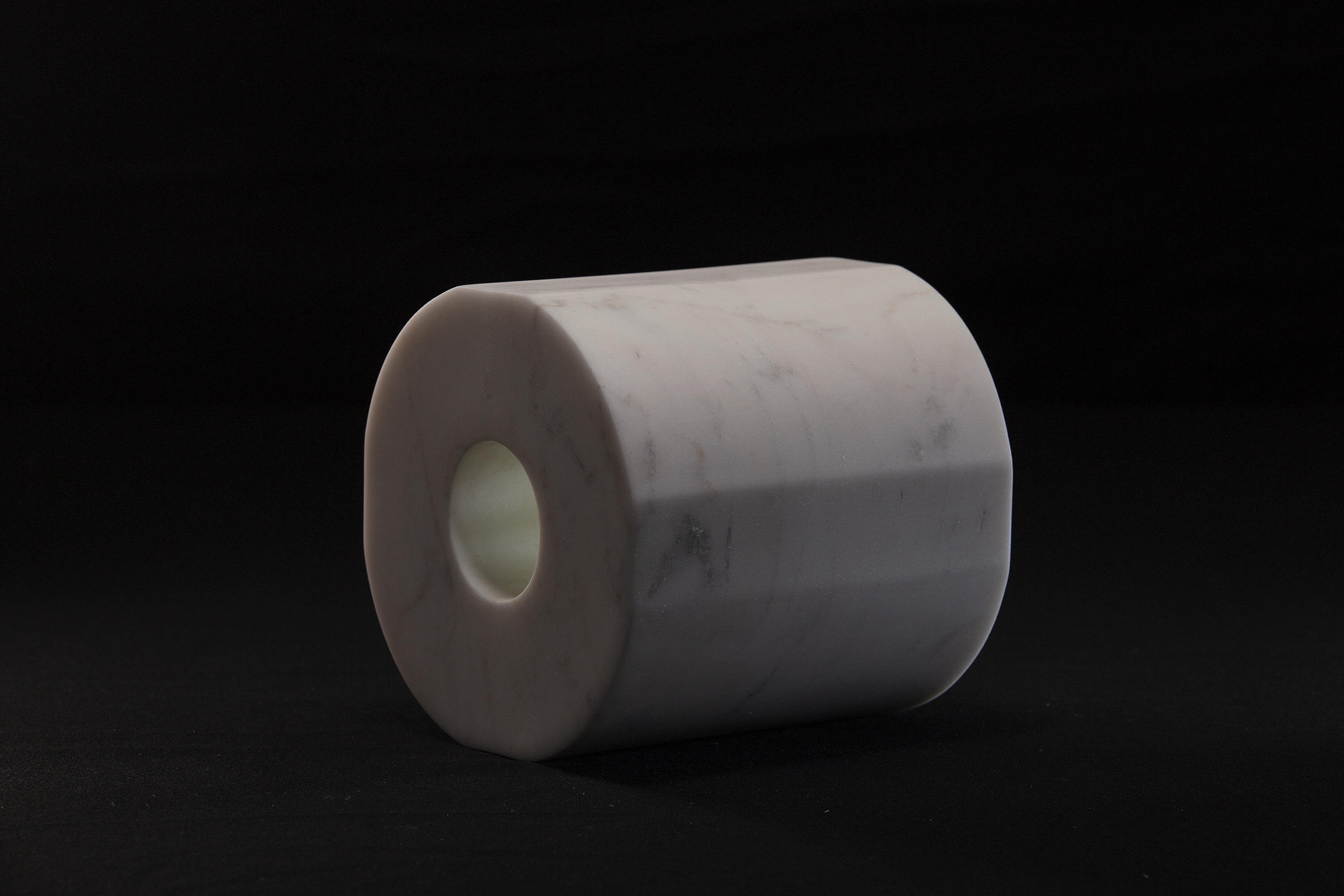

In a large Mahogany display case (made by British Museum to contain Chinese earthenware, now owned by Weiwei) sit a range of marble and jade sculptures, remakes of everyday objects carrying a carved power, carrying stories and meaning. Cosmetics (2013) are jade forms of throwaway plastic cosmetics bottles. Marble Takeout Box (2015) transforms Styrofoam disposability into a permanence.

The cabinet also holds other playful forms – Marble Toilet Paper (2020), made over the pandemic, celebrates an everyday object we rely on but not considered with value by our modern sense of selves. It also has the more serious – Marble Helmet (2015) recreates a builder’s hard-hat, referencing those used by rescue workers saving lives from the rubble of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake in which over 80,000 died.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Architecture has been ever present in Weiwei’s artistic practice. In response to that 2008 earthquake, he created Straight (2008-2012), a vast array of iron bars laid in piles, each a rebar from the substandard collapsed buildings clandestinely collected by Weiwei and his team, then meticulously straightened out as an act of de-traumatising the material, presenting it as evidence. For Remembering (2009) he covered the façade of Munich’s Haus der Kunst with 9,000 schoolchildren’s backpacks, symbolising lives lost as corruption-engineered, state-built schools crumbled. For seven years she lived happily on this earth, the bags spelt in Chinese characters, quoting a mother.

Not long after this work Weiwei was arrested and imprisoned in secret for 81 days, a period of intense and intimate surveillance within a compact cell, an interior he recreated in detail through six scaled dioramas in S.A.C.R.E.D. (2013). That arrest is also referenced here with Handcuffs (2011), a solid marble rendering of those locked onto his wrists. Carved from a single piece of stone, including interlinked chains of immense craftsmanship, there’s an attempt here to make beauty from the profoundly ugly, through tradition, craft, and material.

![]()

fig.viii

In 2007 for documenta 12 in Kassel, Weiwei created Template, an architectural-scale sculpture formed of wooden doors and windows from Ming and Qing Dynasty buildings. Shaped as a cross, at its centre an absence outlined the suggested form of a Chinese temple. It was formed of components salvaged from historic buildings cleared for speculative developments in the Shanxi region, at a time entire towns were demolished for the new. It stood as a form of rescue, reinterpretation, and questioning of value, form, and connection through material.

A storm hit the German town, pulling at the installation, pushing it to the ground. The artist chose to leave it crumpled instead of re-erection, enjoying its poetic return to ruin from a genesis of destruction. He tells me: “The collapse created another form. I always say the art is not the end but the beginning. A challenge to raise questions, raise doubt, rather than to say absolutely: This is the best painting in history. If you said to Van Van Gogh or Rembrandt that they had made the ultimate painting, they would laugh. They would not do another painting.”

![]()

Template, as so much of Weiwei’s work, is about transformation. How events, impositions, opinions, or imposed value systems can shift the meaning or importance of an original object – both through a revaluation of architectural salvage, as well as a change in its own artistic meaning following the collapse. This speaks to the vases downstairs, both the original antiques, and the original fakes. One has more value not because it is inherently better or more functional, but because it has lasted longer, has some patina of meaning through survival and stories picked up along the way.

There is a romance in Weiwei’s approach to material, and a respect given to the everyday or ordinary object as much as the antique or celebrated. He speaks of a sensitivity we have as humans, “we always want to grab something which we identify with - not just the excitement of foreignness, but rather an unspeakable familiarness.” He fears, however, that this sense is nearly destroyed in a time of disposability and dispossession. Material is one way we can keep a connection to the past and future, whether with the jade, the Qing architectural salvage, or a more mundane object:

“I remember my son when he was young, he always wanted to grab one piece of fabric when falling into sleep. But nothing can quite describe why I still keep that piece of fabric. That’s not scientific, one piece of fabric is not much different from another one. But have we lost that? We are lost – but we don’t even know we are lost.”

![]()

fig.x

Weiwei imbues his transformed objects with stories. Referencing the state constantly watching the artist, and his Beijing studio complex surrounded by 24 CCTV cameras, Surveillance Camera with Plinth (2014) is a powerful form solidifying the anxiety the cameras are designed to instill just as much as they are made to observe. Here it sits alongside a Chinese black limestone pedestal oil-lamp from the Northern Wei Dynasty, with squares and circles of its plinth referring to traditional Chinese cosmic symbolism recreated in Weiwei’s marble plinth. There is also the transformation of narrative – where Weiwei has a camera watching over, the ancient lamp would have had a wick floating in vegetable oil, a continuation of an architectural form, but deployed to different political ends.

Three Ai Weiwei films are shown within the Kettle’s Yard exhibition, two of which are new - Coronation (2020), observing Wuhan during the outbreak of Covid-19, and Cockroach (2020) following Hong Kong student activists standing up to the Chinese state in 2019’s pro-democracy protests.[2] Both also show a transformation of built space, and how the personal and political intertwine within infrastructure and architecture.

I think of the marble camera when Cockroach dwells on surveillance infrastructure, and how an historic city can be retrofitted for a totalitarian future. However, the film also shows how the existing city can be co-opted and rearranged by the people themselves, including incredible scenes of construction and defence of barricades formed of urban furniture. The city is both backdrop and protagonist: Groups of youths in yellow helmets – not unlike Weiwei’s marble reproduction – flood down shopping centre elevators armed with umbrellas; blood dribbles on the tarmac; flames lick up a building; a Chinese-owned shopping centre is ransacked.

“I really enjoy becoming part of the city, but the city of course is a huge machine we all become one one part of it – to feel the big machines running – om ta ta, om ta ta,” Weiwei emphasising the mechanical rhythm. In Cockroach we see that system of machinery, of collective organisation but also authoritarian control. The film is incredibly emotional – in both uplifting and terrifying ways.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A drone shot slowly passes over empty and silent post-riot roads. It brings to mind two of Weiwei’s older filmic city studies, Chang’an Boulevard (2004) and Beijing: The Second Ring (2005). Each considers road infrastructure across the capital, transects of time and place observing a place unsettled under rapid economic development. Loss, transformation, and rhythm repeat through Weiwei’s practice, and in photo series Provisional Landscapes (2002-2008) the artist recorded vast urban landscapes razed in preparation of redevelopment. In his blog, Weiwei described these sites as “a void because no one speaks, no one asks the question of who is behind it … a void with many questions, yet people don’t want to look, or raise these questions”.[3] That is, if they are afforded the space and ability to ask the questions.

In today’s culture of demolition and clearance of community for financial uplift, at a time of Evergrande and mass speculative development teetering as nervously as Template before the storm, I ask Weiwei his thoughts on developer-led global architecture, which we can see from Nine Elms to Nanjing:

“Today’s architecture has lost a very essential meaning of architecture – to describe the human's environment with who we are, how we use that architecture, and how to relate it to our moral and aesthetic beliefs. If you just want to make an object or sculpture to be photographed … that's not architecture. That's just an exaggeration of ego.”

I think of the students in Cockroach rearranging the city to their immediate needs, layering new meanings and stories into existing surfaces and materials. Their imagined future would be one built on the traces and layers of the present, not formed from a tabula rasa. Recalling Weiwei’s earlier comment about imagination being “some kind of desire”, I ask if imagination is enough to fight the machinery of such violent power, but he has less optimism: “Well, no imagination can cope with capital - and the desire to fulfil everything with profit.”

This speaks to the theme of the exhibition at Kettle’s Yard, The Liberty of Doubt. Imagination feeds on doubt, and with a totalitarian restriction of questioning and doubt, the space for imagination and creating a future is also closed. Weiwei states that we “…need doubt, doubt is important. And in today's social political situation, there's a tendency to really erase the possibility of doubt. Which is dangerous … your state of mind comes from doubt.”

Since I spoke to Weiwei, the world has shifted gear after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Doubt is a luxury for those who are free enough to consider, be wrong, and personally test or entertain ideas. It is a privilege, and one focused more sharply in light of aggressive authoritarianism.

The troop movements and violence that have unfolded represent a state of violence the artist is not unfamiliar with, telling me that “we are living in a very shattered world - it’s like a stone thrown through a window or mirror, completely shattered that it reflects different images because the angle changed.”

His work in reimagining matter with a simplicity of form, his invocation and rescue of the past before transforming it for future imaginaries, is Weiwei’s way of making sense of that shattering. Throughout his life he has dealt calmly with those shards, and methodically tried to rebuild what remains in the wake of the machinery of politics. It is a stoic and creative approach we may all need, now more than ever as the shattering continues, because, as he tells me, “in the most difficult times only art or poetry can fill the area authoritarians can never touch.”

![]()

fig.xv

[1] See Ai Weiwei’s Blog (2006-2009), published by MIT Press (2011), page 52.

Originally home of Jim and Hellen Ede (Jim had been a Tate curator over the 1920s and 30s), it is formed of four interconnected cottages as a space to not only live but also carefully display their collection of 20th century art and ceramics. Kettle’s Yard is a place rooted in creativity, looking, and slow contemplation, and Weiwei seemed quite at home, settled. I asked if it was a place he was familiar with.

“I have been here many, many times. I feel so familiar to the environment and I feel comfortable, and it feels real, natural. I like it because I feel I belong to it, you know. [Jim Ede] understood how to make his life as art, make art as his life. So, I very much identify to the environment.”

Winter sun floods the window, caressing stones on the sill and rippling the silent floorboards, I wondered if it was something about the surfaces and famed light of the house, how the materials carry a patina of age and aesthetic. “No, it's not nothing about that. It’s about the ordinary feeling of how you can imagine what kind of life used to be in here. So, it’s more information than just space or material. It's a total information,” he laughed.

fig.i

Weiwei may look settled and at home, but it’s a relationship to the domestic which he admits isn’t natural to him. His father, Ai Qing, was also an artist, a poet exiled by the government to Xinjiang in the northwest of China, a landscape of deserts and mountains, suffering a relentless punishment of harsh manual labour. In his blog, which ran for three years from 2006 until the Chinese state shut it down, Weiwei spoke about the domestic space of his childhood:

“My earliest experience with architecture was when I was eight years old, and we were sent down to Xinjiang; as punishment we were forced to live in an earthen pit. I think that in political circumstances like those, living underground can provide an incredible feeling of security - it was a pit dug right into the ground, in the winter it was warm, and in the summer it was cool. Its walls were linked with America, and its roof and floor were flush, and often enough, when pigs would run overhead, their bottoms would fall through our roof, making us too familiar with the sight of swine nether regions.”[1]

His father was too tall for the subterranean space, and so they dug the house deeper to give more headroom – an approach to dealing with architecture, material, and space from a place of simplicity and need - qualities he has taken not only into sculptural works but also architectural projects through his studio, FAKE Design.

Weiwei now lives across Europe, with his main studio in Berlin and primary residence in Portugal. He does, however, have a property in Cambridge after moving to the city in 2019, though says “I cannot call [Cambridge] my home-town, but my residence.” The word home is one he doesn’t quite recognise, adding, “I never had that privilege because I always see myself as a traveller. Every space to me is just the place to prepare me for the next trip.”

This precarious relationship to settling is perhaps contained in both his childhood displacement as well as the constant sense of being followed by the Chinese government. Instead, his rootedness is in creative making, as his father’s was before, something he has written about but still finds hard to speak of - “The story is too dramatic to tell. But all my understanding of art has come from him.”

Creativity comes from a place of need, especially within a climate when an ability to question and propose can be crushed. “What is imagination?” he wonders, “It’s got to be some kind of desire, and it's always about something we don't have. Or it's thinking what would be a good idea if it can exist.”

figs.ii-iv

Scattered around Kettle’s Yard are works by Brancusi, Nicholson, Hepworth, Miró, and Hamilton Finlay amongst many more. Downstairs, in the new Jamie Fobert Architects’ designed gallery, they are joined by Weiwei’s exhibition The Liberty of Doubt, a collection of existing small works exploring value and meaning, alongside a second room with a grid of vitrines of Chinese antiquities bought at a Cambridge. He later discovered a number were fakes, though a typical visitor wouldn’t know which ones were authentic historical objects and which date to the last few decades - it was only through antique expert acquaintances in New York and China that the artist himself was sure which were real and which were fake.

Of course, they are all real, and this is at the heart of Weiwei’s provocation, that even fakes are legitimate art objects with a level of craftsmanship and material knowledge which should be respected and are worthy of exhibition. I thought of these objects when Weiwei made that quip about total information, and how to look beyond knowing something as a binary within a single frame but consider a material or object beyond surface. It touches on value systems and imbued power, as well as social or cultural narratives contained within its history.

Much of Weiwei’s sculptural works are carved from jade, a material he says has “the longest history in human’s fascination with objects”, and a mineral used in Chinese craft for 6,000 years as, he explains, “a tradition which has never stopped, not interrupted by war, or different kinds of religion … an ordinary piece of stone picked up from a river or a mountain range, then given such power by carving it.”

In a large Mahogany display case (made by British Museum to contain Chinese earthenware, now owned by Weiwei) sit a range of marble and jade sculptures, remakes of everyday objects carrying a carved power, carrying stories and meaning. Cosmetics (2013) are jade forms of throwaway plastic cosmetics bottles. Marble Takeout Box (2015) transforms Styrofoam disposability into a permanence.

The cabinet also holds other playful forms – Marble Toilet Paper (2020), made over the pandemic, celebrates an everyday object we rely on but not considered with value by our modern sense of selves. It also has the more serious – Marble Helmet (2015) recreates a builder’s hard-hat, referencing those used by rescue workers saving lives from the rubble of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake in which over 80,000 died.

figs.v-vii

Architecture has been ever present in Weiwei’s artistic practice. In response to that 2008 earthquake, he created Straight (2008-2012), a vast array of iron bars laid in piles, each a rebar from the substandard collapsed buildings clandestinely collected by Weiwei and his team, then meticulously straightened out as an act of de-traumatising the material, presenting it as evidence. For Remembering (2009) he covered the façade of Munich’s Haus der Kunst with 9,000 schoolchildren’s backpacks, symbolising lives lost as corruption-engineered, state-built schools crumbled. For seven years she lived happily on this earth, the bags spelt in Chinese characters, quoting a mother.

Not long after this work Weiwei was arrested and imprisoned in secret for 81 days, a period of intense and intimate surveillance within a compact cell, an interior he recreated in detail through six scaled dioramas in S.A.C.R.E.D. (2013). That arrest is also referenced here with Handcuffs (2011), a solid marble rendering of those locked onto his wrists. Carved from a single piece of stone, including interlinked chains of immense craftsmanship, there’s an attempt here to make beauty from the profoundly ugly, through tradition, craft, and material.

fig.viii

In 2007 for documenta 12 in Kassel, Weiwei created Template, an architectural-scale sculpture formed of wooden doors and windows from Ming and Qing Dynasty buildings. Shaped as a cross, at its centre an absence outlined the suggested form of a Chinese temple. It was formed of components salvaged from historic buildings cleared for speculative developments in the Shanxi region, at a time entire towns were demolished for the new. It stood as a form of rescue, reinterpretation, and questioning of value, form, and connection through material.

A storm hit the German town, pulling at the installation, pushing it to the ground. The artist chose to leave it crumpled instead of re-erection, enjoying its poetic return to ruin from a genesis of destruction. He tells me: “The collapse created another form. I always say the art is not the end but the beginning. A challenge to raise questions, raise doubt, rather than to say absolutely: This is the best painting in history. If you said to Van Van Gogh or Rembrandt that they had made the ultimate painting, they would laugh. They would not do another painting.”

fig.ix

Template, as so much of Weiwei’s work, is about transformation. How events, impositions, opinions, or imposed value systems can shift the meaning or importance of an original object – both through a revaluation of architectural salvage, as well as a change in its own artistic meaning following the collapse. This speaks to the vases downstairs, both the original antiques, and the original fakes. One has more value not because it is inherently better or more functional, but because it has lasted longer, has some patina of meaning through survival and stories picked up along the way.

There is a romance in Weiwei’s approach to material, and a respect given to the everyday or ordinary object as much as the antique or celebrated. He speaks of a sensitivity we have as humans, “we always want to grab something which we identify with - not just the excitement of foreignness, but rather an unspeakable familiarness.” He fears, however, that this sense is nearly destroyed in a time of disposability and dispossession. Material is one way we can keep a connection to the past and future, whether with the jade, the Qing architectural salvage, or a more mundane object:

“I remember my son when he was young, he always wanted to grab one piece of fabric when falling into sleep. But nothing can quite describe why I still keep that piece of fabric. That’s not scientific, one piece of fabric is not much different from another one. But have we lost that? We are lost – but we don’t even know we are lost.”

fig.x

Weiwei imbues his transformed objects with stories. Referencing the state constantly watching the artist, and his Beijing studio complex surrounded by 24 CCTV cameras, Surveillance Camera with Plinth (2014) is a powerful form solidifying the anxiety the cameras are designed to instill just as much as they are made to observe. Here it sits alongside a Chinese black limestone pedestal oil-lamp from the Northern Wei Dynasty, with squares and circles of its plinth referring to traditional Chinese cosmic symbolism recreated in Weiwei’s marble plinth. There is also the transformation of narrative – where Weiwei has a camera watching over, the ancient lamp would have had a wick floating in vegetable oil, a continuation of an architectural form, but deployed to different political ends.

Three Ai Weiwei films are shown within the Kettle’s Yard exhibition, two of which are new - Coronation (2020), observing Wuhan during the outbreak of Covid-19, and Cockroach (2020) following Hong Kong student activists standing up to the Chinese state in 2019’s pro-democracy protests.[2] Both also show a transformation of built space, and how the personal and political intertwine within infrastructure and architecture.

I think of the marble camera when Cockroach dwells on surveillance infrastructure, and how an historic city can be retrofitted for a totalitarian future. However, the film also shows how the existing city can be co-opted and rearranged by the people themselves, including incredible scenes of construction and defence of barricades formed of urban furniture. The city is both backdrop and protagonist: Groups of youths in yellow helmets – not unlike Weiwei’s marble reproduction – flood down shopping centre elevators armed with umbrellas; blood dribbles on the tarmac; flames lick up a building; a Chinese-owned shopping centre is ransacked.

“I really enjoy becoming part of the city, but the city of course is a huge machine we all become one one part of it – to feel the big machines running – om ta ta, om ta ta,” Weiwei emphasising the mechanical rhythm. In Cockroach we see that system of machinery, of collective organisation but also authoritarian control. The film is incredibly emotional – in both uplifting and terrifying ways.

figs.xi-xiv

A drone shot slowly passes over empty and silent post-riot roads. It brings to mind two of Weiwei’s older filmic city studies, Chang’an Boulevard (2004) and Beijing: The Second Ring (2005). Each considers road infrastructure across the capital, transects of time and place observing a place unsettled under rapid economic development. Loss, transformation, and rhythm repeat through Weiwei’s practice, and in photo series Provisional Landscapes (2002-2008) the artist recorded vast urban landscapes razed in preparation of redevelopment. In his blog, Weiwei described these sites as “a void because no one speaks, no one asks the question of who is behind it … a void with many questions, yet people don’t want to look, or raise these questions”.[3] That is, if they are afforded the space and ability to ask the questions.

In today’s culture of demolition and clearance of community for financial uplift, at a time of Evergrande and mass speculative development teetering as nervously as Template before the storm, I ask Weiwei his thoughts on developer-led global architecture, which we can see from Nine Elms to Nanjing:

“Today’s architecture has lost a very essential meaning of architecture – to describe the human's environment with who we are, how we use that architecture, and how to relate it to our moral and aesthetic beliefs. If you just want to make an object or sculpture to be photographed … that's not architecture. That's just an exaggeration of ego.”

I think of the students in Cockroach rearranging the city to their immediate needs, layering new meanings and stories into existing surfaces and materials. Their imagined future would be one built on the traces and layers of the present, not formed from a tabula rasa. Recalling Weiwei’s earlier comment about imagination being “some kind of desire”, I ask if imagination is enough to fight the machinery of such violent power, but he has less optimism: “Well, no imagination can cope with capital - and the desire to fulfil everything with profit.”

This speaks to the theme of the exhibition at Kettle’s Yard, The Liberty of Doubt. Imagination feeds on doubt, and with a totalitarian restriction of questioning and doubt, the space for imagination and creating a future is also closed. Weiwei states that we “…need doubt, doubt is important. And in today's social political situation, there's a tendency to really erase the possibility of doubt. Which is dangerous … your state of mind comes from doubt.”

Since I spoke to Weiwei, the world has shifted gear after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Doubt is a luxury for those who are free enough to consider, be wrong, and personally test or entertain ideas. It is a privilege, and one focused more sharply in light of aggressive authoritarianism.

The troop movements and violence that have unfolded represent a state of violence the artist is not unfamiliar with, telling me that “we are living in a very shattered world - it’s like a stone thrown through a window or mirror, completely shattered that it reflects different images because the angle changed.”

His work in reimagining matter with a simplicity of form, his invocation and rescue of the past before transforming it for future imaginaries, is Weiwei’s way of making sense of that shattering. Throughout his life he has dealt calmly with those shards, and methodically tried to rebuild what remains in the wake of the machinery of politics. It is a stoic and creative approach we may all need, now more than ever as the shattering continues, because, as he tells me, “in the most difficult times only art or poetry can fill the area authoritarians can never touch.”

fig.xv

[1] See Ai Weiwei’s Blog (2006-2009), published by MIT Press (2011), page 52.

[2] Ai Weiwei’s films are available to view online for a small price at www.aiweiwei.com

[3] Ai Weiwei in Ai Weiwei: Spatial Matters: Art, Architecture and Activisim, by Ai Weiwei and Anthony Pins, published MIT Press, p.336

Ai Weiwei is a global citizen, artist and thinker, moving between modes of production and investigation, subject

to the direction and outcome of his research. Ai’s production

expanded to encompass architecture, public art and performance. Beyond concerns of form or protest, Ai now measures our existence in relation to economic,

political, natural and social forces, uniting craftsmanship with conceptual creativity. Universal symbols of humanity and community, such as bicycles, flowers and

trees, as well as the perennial problems of borders and conflicts are given renewed potency through

installations, sculptures, films and photographs, while Ai continues to speak out publicly on issues he believes important. He is one of the leading cultural figures of his

generation and serves as an example for free expression both in China and internationally.

www.lissongallery.com/artists/ai-weiwei

Kettle’s Yard is the University of Cambridge’s modern and contemporary art gallery. Kettle’s Yard is a beautiful House with a remarkable collection of modern art and a gallery that hosts modern and contemporary art exhibitions.

www.kettlesyard.co.uk/events/ai-weiwei-the-liberty-of-doubt

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

images

fig.i Ai Weiwei portrait, 2022. P

hotograph by Gao Yuan © Ai Weiwei Studio, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

fig.ii-iv The Liberty of Doubt, by 2022. Installation images. © Jo Underhill

fig.v Marble Takeout Box, by Ai Weiwei, 2015.

© Jo Underhill

fig.vi Marble Toilet Paper, by Ai Weiwei, 2020.

© Jo Underhill

fig.vii Handcuffs, by Ai Weiwei, 2011.

© Jo Underhill

fig.viii Template, by Ai Weiwei, 2007. © documenta archiv, photograph by Monika Nikoilic

fig.ix Template, by Ai Weiwei, 2007. © David Gómez Fontanills

fig.x Surveillance Camera with Plinth, by Ai Weiwei, 2014 (l), and

A Chinese black limestone pedestal oil-lamp, Northern Wei Dynasty (r)

. © Will Jennings

fig.xi Coronation, by Ai Weiwei, 2020.

© Jo Underhill

fig.xii Cockroach, by Ai Weiwei, 2020. © Jo Underhill

fig.xiii Beijing: The Second Ring, by Ai Weiwei, 2005, at 1hr 6mins

© Ai Weiwei, Courtesy Lisson

Gallery

fig.xiv Chang’an Boulevard, by Ai Weiwei, 2004,

at 10hrs 13mins

© Ai Weiwei, Courtesy Lisson

Gallery

fig.xv Portrait of Ai Weiwei, 2020. © Thierry Bal

publication date

28 February January 2022

tags

Architecture, Activism, Antiques, Beijing, Cambridge, Craft, Covid, Documenta, Domestic, Film, Hong Kong, Home, Infrastructure, Jade, Will Jennings, Kettle’s Yard, Landscape, Lisson Gallery, Marble, Material, Politics, Protest, Sculpture, Ai Weiwei

fig.ii-iv The Liberty of Doubt, by 2022. Installation images. © Jo Underhill

fig.v Marble Takeout Box, by Ai Weiwei, 2015. © Jo Underhill

fig.vi Marble Toilet Paper, by Ai Weiwei, 2020. © Jo Underhill

fig.vii Handcuffs, by Ai Weiwei, 2011. © Jo Underhill

fig.viii Template, by Ai Weiwei, 2007. © documenta archiv, photograph by Monika Nikoilic

fig.ix Template, by Ai Weiwei, 2007. © David Gómez Fontanills

fig.x Surveillance Camera with Plinth, by Ai Weiwei, 2014 (l), and A Chinese black limestone pedestal oil-lamp, Northern Wei Dynasty (r) . © Will Jennings

fig.xi Coronation, by Ai Weiwei, 2020. © Jo Underhill

fig.xii Cockroach, by Ai Weiwei, 2020. © Jo Underhill

fig.xiii Beijing: The Second Ring, by Ai Weiwei, 2005, at 1hr 6mins

© Ai Weiwei, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

fig.xiv Chang’an Boulevard, by Ai Weiwei, 2004, at 10hrs 13mins

© Ai Weiwei, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

fig.xv Portrait of Ai Weiwei, 2020. © Thierry Bal

publication date

28 February January 2022

tags

Architecture, Activism, Antiques, Beijing, Cambridge, Craft, Covid, Documenta, Domestic, Film, Hong Kong, Home, Infrastructure, Jade, Will Jennings, Kettle’s Yard, Landscape, Lisson Gallery, Marble, Material, Politics, Protest, Sculpture, Ai Weiwei