Deeper than surface: an interview with Navine G. Dossos

Navine G. Dossos is an artist who creates murals, but her interest in the applied imagery goes deeper than the surface of a wall. With research & interest in Ottoman art & Islamic geometry, she applies the language of glyph as a communication to discuss Orientalism, architecture, otherness, & concerns of contemporary society. In this interview with Will Jennings, Dossos talks about how architecture intersects with her practice.

I asked about the HSBC logo running horizontally across

the wall, not far fom the Mastercard one. I got a puzzled look

in reply. Then after a pause, “Oh, I know exactly which one you mean when you say that – and actually

when I first saw it, I saw the target and negatives. That’s one thing I am

interested in is on old buildings, when you have the little targets for lasers

when they’re checking to see if the building is moving.”

![]()

I was talking to artist Navine G. Dossos about her mural work Ta Nea Xysta (2021), a black and white wall of glyphs which acted as temporal entrance to the former Santaroza Courthouse, one of the hub buildings for Athens Biennale. Her design was deliberately open to interpretation, and if it was graphical Rorschach test then I began to wonder why I saw decorative images of financial organisations while Dossos saw markers of fragility.

“I don't see this work is purely decorative. It tends to have meanings in it and it's for the viewer to try and understand how the meanings reflect specificity of the site or the or the subject matter. When I build images they're not abstract, I tend to think of them informationally. I might use a 12-pointed star if I'm talking about authority, 12 is the number of authority often, you have 12 members of the jury or 12 seasons. But I've also recently started to think more about symbols of our own time, specific to our contemporary moment. The Twitter bird, or Covid, or Wi-Fi, and I think that while people maybe don’t recognise the meaning of a triangle and as having spiritual meaning, they know what a Twitter bird is immediately.”

Looking into the Athens mural, I now see the Twitter, Covid, and Wi-Fi signifiers, alongside others I don’t recognise (if they are even designed to be recognisable), and more which are more universal, classically held forms – like the justice scales touching on the building’s former use. What I thought was a rotated Mastercard logo was in fact “the sun and moon and cycles of seasons”, the role of iconography as a timeless and ongoing universal language shifting from local agricultural to international capital. At the bottom of the work a vertical motif repeated, Dossos telling me they are tassels of a rug which once would have hung over the building as architectural cloak.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Dossos studied History of Art in England, Arabic in Kuwait, and then Islamic Art and an MA in Fine art in London, and it’s this shifting between east and west, and ancient modern practices, which define her practice.

“My background is in Ottoman art and architecture, and part of that training was to think about geometry particularly as an aniconic language, a nonfigurative language but actually containing meaning. In Islamic tradition - and many other traditions as well - geometry itself is quite symbolic of certain terms and ideas. Geometric structures are not just pretty patterns, they actually mean something. Even in architecture, the joining of a sphere or dome with the square building - the square is always the earth and the dome and the circle is the heavens. So a building that that joins those two tends to be a sacred space. And that gets more complicated as you get five sided shapes and sizes and so on.”

Both art and architecture are perhaps overly dominated by the surface. A building cannot be understood or judged solely from its skin, but also an artwork contains within its aesthetic a depth of art-historical connections, ideas, and meanings which take deeper looking or knowing. The skin, however, is important, and can act as conduit to that deeper knowing. The Athens mural was a temporary installation, the entrance architecture it created transforming the usual façade of a building locals would have been familiar with, though likely not entered in its disused state – both the architectural form and the graphical detail acting as invitation:

“A lot of people would have seen this work without necessarily knowing what the Bienniale was about or that it exists, but because they’re Greek, they recognise this type of design, this decoration. I really wanted to make it for the local audience, for them to have a sense of familiarity but then potentially strangeness, and when getting close go ‘that's a Wi-Fi symbol, what is it doing there?’ So it's a familiarity and the slightly strange that I’m playing with.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.iii

The approach of drawing an audience in with aesthetics, then allowing time to slowly consider the form and meaning, repeats in Dossos’ approach, and when the underlying subject matter is darker it can be a way of holding back the shock and allowing

“It's a way of getting people into the surface, and into a subject, because I think a lot of the work I’ve done in the past the subjects aren't necessarily very nice or comfortable, but if people are drawn to pattern and decoration things are naturally quite ordered, and if you draw them in and you get them to pay attention, then they can unpick the work, and it reveals something. It's not an aggression - a lot of the work is aggressive, but it's not an aggression in that sense. I think it gives people a moment of meditation to just be with thing and the ideas of the thing, so the confrontation unfolds.”

I like this idea of an unfolding confrontation, and how through an art object an alien, forceful, progressive, or counter argument can be made, but through an oblique or tangential communication which demands slow reception. In an age of immediacy and binary, it’s a form of delivery which could be valuable.

“I think that's why I make murals. I'm interested in a person being surrounded by a painting, that they’re enveloped in it, they’re in the idea. Like the Rothko Chapel, being surrounded by a painting as sensation, a painting holding space for an idea and being able to take time with it.”

![]()

fig.iv

For the Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art group exhibition Testament, which invited 45 artists to consider what monuments could mean in today’s climate, Dossos created BLE (2022). A small photograph pinned to the wall, it shows a public sculpture formed of ten circles with the logo of a person within, interconnected with thin spindles and mounted on a base carved wit the phrase “2.402 Ghz – 2.48 GHz”. The public square it sits within seems devoid of people, yet its very form conjures ideas of networking, interconnectivity, and – in a time of Covid – social bubbles.

The title is short for Bluetooth Low Energy, the always-on connections between mobile devices which is the root of Covid apps which monitored our proximity to others. Such tracing apps were banned in some states, including Norway and Lithuania, on the basis of data privacy concerns. There is also a connection here to hi-tech companies such as Israel’s NSO, who within the pandemic adapted their infamous Pegasus spyware into Covid contact tracing software.

“The question of contact tracing varies in different places, and people's trust technology varies in different places. I wanted to make a monument that was a bit of a grey area - it's both a celebration and a warning. Something I didn't want it to be was a gesture of heroics. I wanted it to be a kind of boundary of a moment, or the marking of a moment in time.”

The sculpture of heroics, or more commonly the white, male hero, is a legacy not uncommon in our cities and public spaces. I asked about the Edward Colston statue in Bristol, ceremoniously de-plinthed and plunged into the Avon, and how it was erected as an heroic monument by a group of people who wanted to reinforce and sustain a legacy of power and class which he and it symbolised, but how by remaining up for so long it became a monument as warning.

Dossos’ sculpture, however, only exists as this image. It is a digital render, as if for a planning application which will never be submitted. Working with Greek designer Dimitris Papousakis, who creates 3D renders for architectural firms, the piece was designed for Victoria Square in the centre of Athens. It’s a specific site. Built into the render is its very impossibility - the spindles are too slender to support black marble, the heads of the logo-characters appear to be floating unsupported – a play between what can exist, what’s possible and what’s utopian imaginary.

“It is where a lot of the refugees arrive in Athens, a real hotspot in 2015 when I first arrived in Greece. This is a place that is kind of untouched by contact tracing in a way because I feel a lot of people who are in the space probably aren't traced in that way. But where could you ever put up a monument like this in London? Kings Cross? Next to the Google building? We were trying to choose an urban space and ended up with Victoria Square, but I think the idea of it being a truly public space is quite important.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.v

The sculpture also acts as a graphical form, as other works have, touching back on the relationship between logomark or glypth and abstract artwork. This is the case with a series of works from 2012-13, each showing a rotated grid of rigid geometric forms. They could be mappings of modernist housing, or the underlying grid of semiconductors, maybe a QR code. The mind wonders as it looks at the arrangements. They are in fact aerial calibrations, vast interventions in desert landscapes used for surveillance and calibration of cameras from satellites and aircraft.

The desert landscapes in which these land-art-like symbols sit is of interest to Dossos, who lived in Kuwait when the second Iraq war began, an event she describes as being “massively formative for me, politically. In Kuwait the desert was a place you didn’t go, because it was full of mines from the first Gulf War. So not only was stuff going up through Kuwait into Iraq at the time, but it wasn't really a space you could go and spend time in any way, because it was dangerous.”

As well as a space of potential physical danger, the desert has been a figurative stand in for otherness from a western and predominantly white canon. A uniform aesthetic into which presumption, colonial- and post-colonialism, shorthand narratives, and racialised stereotyping can be loaded into a heady mix of exoticness.

“When I studied Ottoman art and architecture [I was interested in a] post-colonial approach to reading Orientalist architecture in a western context, so it was very much a critical view of how, for example, mosque architecture became pavilions and spaces to have tea. That’s always fascinated me - there was a power structure involved in doing this that needed to be spoken about. The desert has always been this kind of space of incredible imagination for the West, and for many writers and artists in particular.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.vi

One artist is Richard Dadd, 19th century British watercolourist who travelled through the lands west of Iraq as artist-accompaniment Welshman Sir Thomas Phillips on his Grand Tour through Venice, Greece and Egypt. On the trip, Dadd had a breakdown, returned to England and tragically murdered his father before being locked up in Bethlem Hospital, where he continued to paint.

Dossos’ mural installation Komt Hier Aan Deze Gele Vlaktes (Come Unto These Yellow Sands) (2015) takes its name from an 1842 Dadd painting, in turn drawing its title from Ariel’s song in Act I, Scene II of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. It was a work for Probe, a physical 6.6m² space only viewable by the public online as a Dutch project running from 2008-2019.

“I wanted to think more about the idea of an interior desert, in the Netherlands there is actually a desert, a lot of sand that came from a glacier is right in the centre of the Netherlenads as a desert. I wanted to say that sometimes you have to stop looking for the other on the outside and actually look for the desert within, and for the otherness within yourself - instead of the exoticisation of the other, or the desert of Arabia, we need to examine these things that exist within ourselves. That’s why it’s also referencing Dadd, somebody who really looked for these interior landscapes with an incredible imagination that came from within himself - he also spent time in Egypt and there is a whole Orientalist conversation to be had about what happened to him before he killed his father.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.vii

The duality of symbolism in landscape and nature runs through Dossos’ work. Another project, Imagine a Palm Tree (2016) explores just this, through the history of palm trees in Athens. The artist had moved to Athens the previous year, and heard a story told repeatedly with slight variations which spoke about the city once being covered in palm trees before being removed to make the city appear more European and less Orientalwith only a few remaining in the botanical gardens and surrounding churches.

“Palm trees used to exist in Athens and had done for centuries, and when the Ottomans were kicked out and Athens specifically became the centre of the new independent Greece that was very much framed around a kind of northern European notion of what Hellenic culture should look like, all the palm trees were basically cut down because they made it look to African or exotic, or oriental. They were only brought back for the [2004] Olympic Games, when they had a completely different meaning of luxury and summer holidays, so the whole meaning of this tree had changed.”

Dossos used the motif of the palm tree within the café of the Benaki Museum’s Islamic Art Collection, showing the tree, its leaves, and roots penetrating a CCTV infused sky and metro-excavated depths as a continuity, speaking to all versions of place, including those not visible at first glance.

![]()

![]()

![]()

For A Year Without Movement (2017), Dossos made visible more unseen urbanity. The House of Saint Barnabas - a Grade I listed building, ethical members club, and homeless charity - found itself directly above the subterranean digging for London’s Crossrail railway line. The artist created a series of site specific wall paintings throughout the panelled interior, pulling symbols of Crossrail into the building above, itself being precariously observed for movement and subsidence as engineering took place below.

“Crossrail is a massive undertaking, churning up earth underneath, doing something very profound to the city. The very ground these buildings are standing on is affected and there is a fragility of the structures that needs to be recognised, especially somewhere like Soho – these buildings are so familiar, they seem so solid, and so present.”

Dossos is inquiring about the perceived strength of our architectures – and the institutions, social contracts, economies, and structures which shape the city. She used to walk past the House of Saint Barnabas as a child, and growing older began to understand its history as a space of security and safety, especially for women, and through this how the very ecosystem of the city is as precarious as the heritage which holds it.

“The systems are fragile and the building is fragile, because of this other kind of system underneath. But if we can make visible some of those systems perhaps it give us an understanding of what's happening. The intention is to try and bring about a conversation about what's happening and how these things affect each other, how that digging and creation of new links can undermine a building, but also other kinds of social structures as well.”

The construction of Crossrail, as with all urban infrastructure, will see tectonic plates of value, cost of living, regeneration, and development shift, and with that who can call London home, and who has none.

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.ix

This touches on Dossos’ next project, and (on a personal level at least) the most personal and important – a house for her family: “My partner and I are planning to self-build our own house over the next few years, using the Walter Segal method, mixing it with more Greek vernacular architectures and using local materials. I think it's an interesting progression for me to go from not just painting the wall but making the wall - making the structure and understanding it fundamentally. I don't want to take the structure for granted any more, but to really think about what it means to make that structure and the volumes of it as well.”

![]()

fig.x

fig.i

I was talking to artist Navine G. Dossos about her mural work Ta Nea Xysta (2021), a black and white wall of glyphs which acted as temporal entrance to the former Santaroza Courthouse, one of the hub buildings for Athens Biennale. Her design was deliberately open to interpretation, and if it was graphical Rorschach test then I began to wonder why I saw decorative images of financial organisations while Dossos saw markers of fragility.

“I don't see this work is purely decorative. It tends to have meanings in it and it's for the viewer to try and understand how the meanings reflect specificity of the site or the or the subject matter. When I build images they're not abstract, I tend to think of them informationally. I might use a 12-pointed star if I'm talking about authority, 12 is the number of authority often, you have 12 members of the jury or 12 seasons. But I've also recently started to think more about symbols of our own time, specific to our contemporary moment. The Twitter bird, or Covid, or Wi-Fi, and I think that while people maybe don’t recognise the meaning of a triangle and as having spiritual meaning, they know what a Twitter bird is immediately.”

Looking into the Athens mural, I now see the Twitter, Covid, and Wi-Fi signifiers, alongside others I don’t recognise (if they are even designed to be recognisable), and more which are more universal, classically held forms – like the justice scales touching on the building’s former use. What I thought was a rotated Mastercard logo was in fact “the sun and moon and cycles of seasons”, the role of iconography as a timeless and ongoing universal language shifting from local agricultural to international capital. At the bottom of the work a vertical motif repeated, Dossos telling me they are tassels of a rug which once would have hung over the building as architectural cloak.

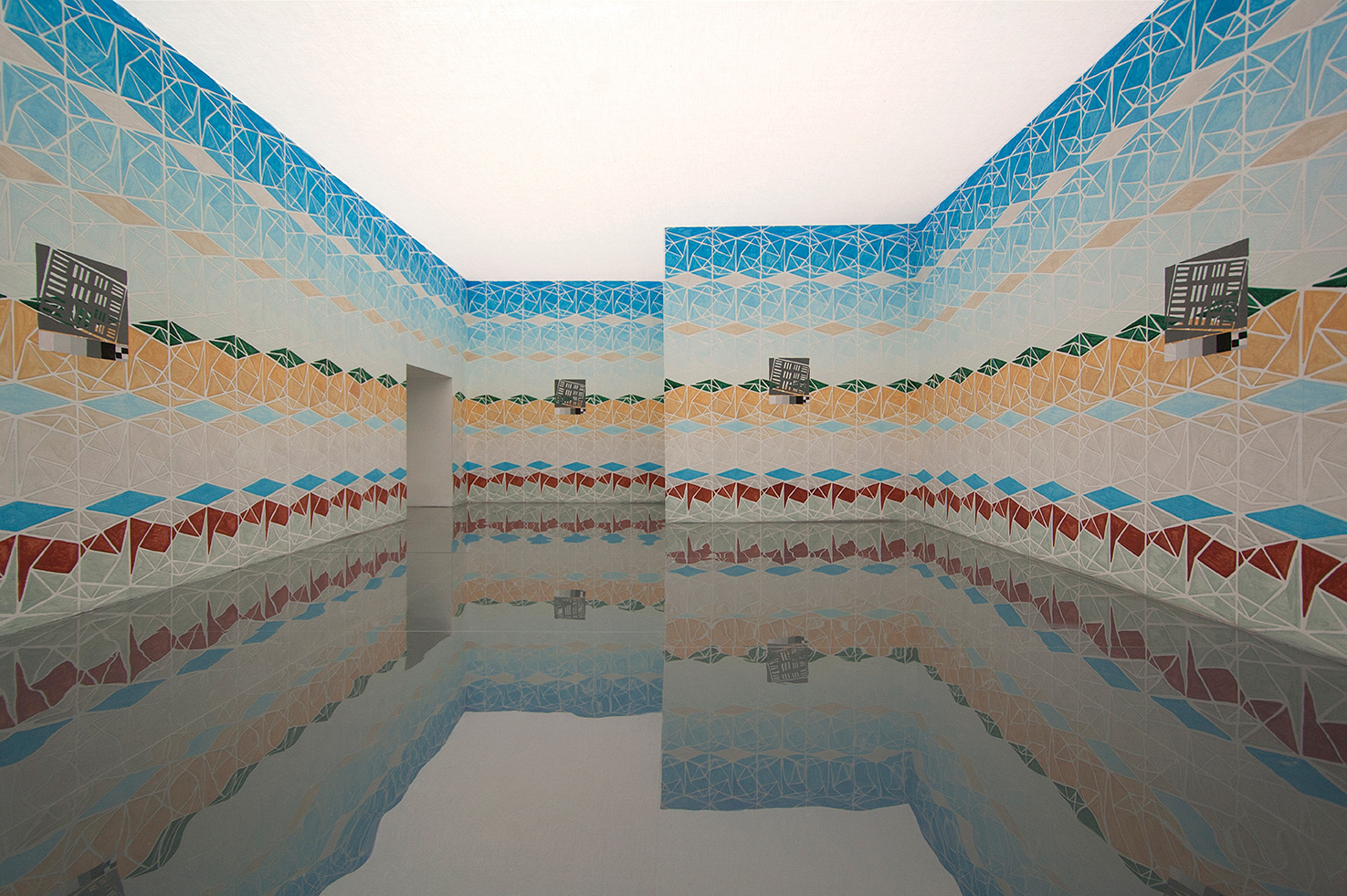

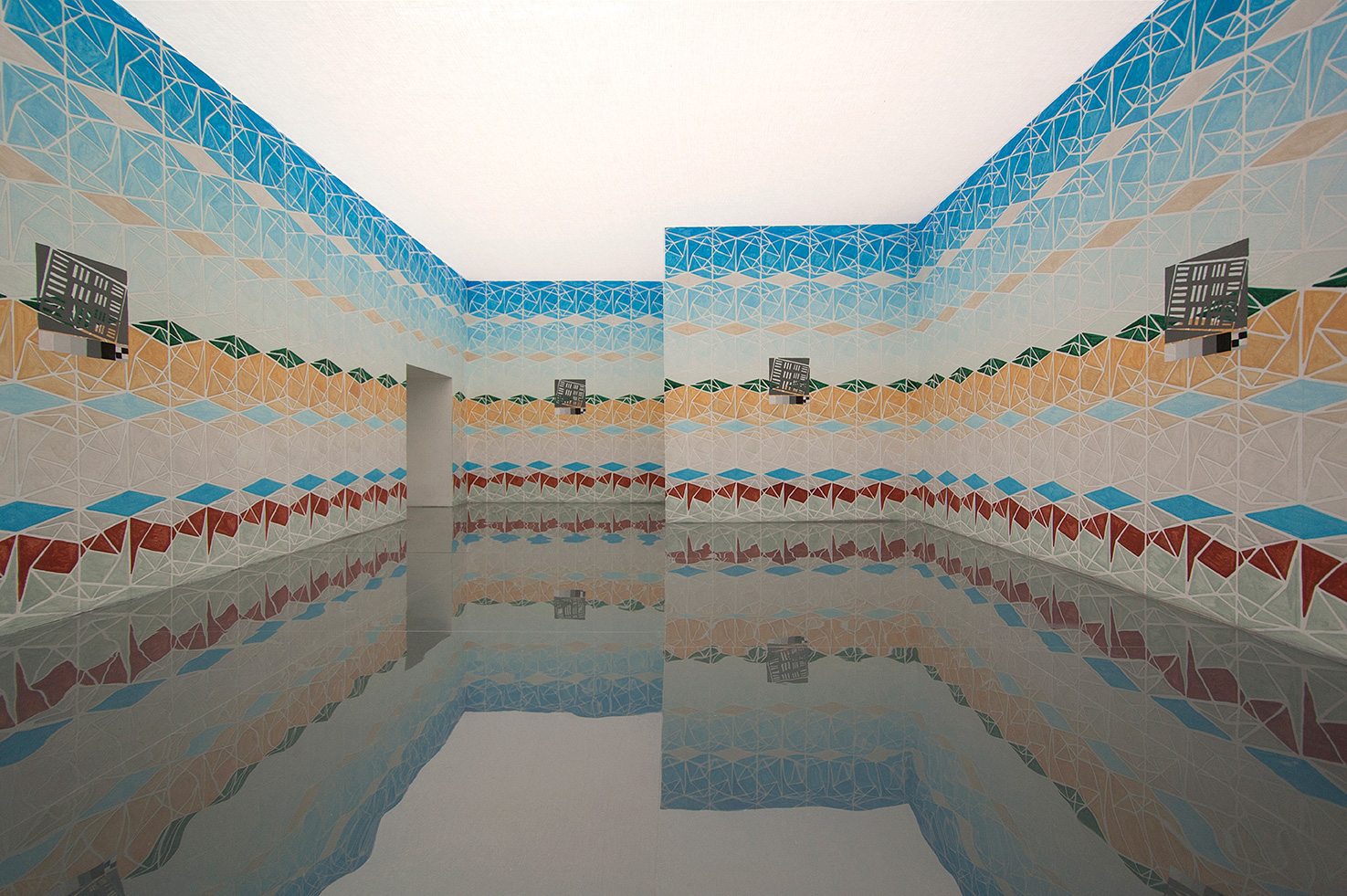

figs.ii

Dossos studied History of Art in England, Arabic in Kuwait, and then Islamic Art and an MA in Fine art in London, and it’s this shifting between east and west, and ancient modern practices, which define her practice.

“My background is in Ottoman art and architecture, and part of that training was to think about geometry particularly as an aniconic language, a nonfigurative language but actually containing meaning. In Islamic tradition - and many other traditions as well - geometry itself is quite symbolic of certain terms and ideas. Geometric structures are not just pretty patterns, they actually mean something. Even in architecture, the joining of a sphere or dome with the square building - the square is always the earth and the dome and the circle is the heavens. So a building that that joins those two tends to be a sacred space. And that gets more complicated as you get five sided shapes and sizes and so on.”

Both art and architecture are perhaps overly dominated by the surface. A building cannot be understood or judged solely from its skin, but also an artwork contains within its aesthetic a depth of art-historical connections, ideas, and meanings which take deeper looking or knowing. The skin, however, is important, and can act as conduit to that deeper knowing. The Athens mural was a temporary installation, the entrance architecture it created transforming the usual façade of a building locals would have been familiar with, though likely not entered in its disused state – both the architectural form and the graphical detail acting as invitation:

“A lot of people would have seen this work without necessarily knowing what the Bienniale was about or that it exists, but because they’re Greek, they recognise this type of design, this decoration. I really wanted to make it for the local audience, for them to have a sense of familiarity but then potentially strangeness, and when getting close go ‘that's a Wi-Fi symbol, what is it doing there?’ So it's a familiarity and the slightly strange that I’m playing with.”

figs.iii

The approach of drawing an audience in with aesthetics, then allowing time to slowly consider the form and meaning, repeats in Dossos’ approach, and when the underlying subject matter is darker it can be a way of holding back the shock and allowing

“It's a way of getting people into the surface, and into a subject, because I think a lot of the work I’ve done in the past the subjects aren't necessarily very nice or comfortable, but if people are drawn to pattern and decoration things are naturally quite ordered, and if you draw them in and you get them to pay attention, then they can unpick the work, and it reveals something. It's not an aggression - a lot of the work is aggressive, but it's not an aggression in that sense. I think it gives people a moment of meditation to just be with thing and the ideas of the thing, so the confrontation unfolds.”

I like this idea of an unfolding confrontation, and how through an art object an alien, forceful, progressive, or counter argument can be made, but through an oblique or tangential communication which demands slow reception. In an age of immediacy and binary, it’s a form of delivery which could be valuable.

“I think that's why I make murals. I'm interested in a person being surrounded by a painting, that they’re enveloped in it, they’re in the idea. Like the Rothko Chapel, being surrounded by a painting as sensation, a painting holding space for an idea and being able to take time with it.”

fig.iv

For the Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art group exhibition Testament, which invited 45 artists to consider what monuments could mean in today’s climate, Dossos created BLE (2022). A small photograph pinned to the wall, it shows a public sculpture formed of ten circles with the logo of a person within, interconnected with thin spindles and mounted on a base carved wit the phrase “2.402 Ghz – 2.48 GHz”. The public square it sits within seems devoid of people, yet its very form conjures ideas of networking, interconnectivity, and – in a time of Covid – social bubbles.

The title is short for Bluetooth Low Energy, the always-on connections between mobile devices which is the root of Covid apps which monitored our proximity to others. Such tracing apps were banned in some states, including Norway and Lithuania, on the basis of data privacy concerns. There is also a connection here to hi-tech companies such as Israel’s NSO, who within the pandemic adapted their infamous Pegasus spyware into Covid contact tracing software.

“The question of contact tracing varies in different places, and people's trust technology varies in different places. I wanted to make a monument that was a bit of a grey area - it's both a celebration and a warning. Something I didn't want it to be was a gesture of heroics. I wanted it to be a kind of boundary of a moment, or the marking of a moment in time.”

The sculpture of heroics, or more commonly the white, male hero, is a legacy not uncommon in our cities and public spaces. I asked about the Edward Colston statue in Bristol, ceremoniously de-plinthed and plunged into the Avon, and how it was erected as an heroic monument by a group of people who wanted to reinforce and sustain a legacy of power and class which he and it symbolised, but how by remaining up for so long it became a monument as warning.

Dossos’ sculpture, however, only exists as this image. It is a digital render, as if for a planning application which will never be submitted. Working with Greek designer Dimitris Papousakis, who creates 3D renders for architectural firms, the piece was designed for Victoria Square in the centre of Athens. It’s a specific site. Built into the render is its very impossibility - the spindles are too slender to support black marble, the heads of the logo-characters appear to be floating unsupported – a play between what can exist, what’s possible and what’s utopian imaginary.

“It is where a lot of the refugees arrive in Athens, a real hotspot in 2015 when I first arrived in Greece. This is a place that is kind of untouched by contact tracing in a way because I feel a lot of people who are in the space probably aren't traced in that way. But where could you ever put up a monument like this in London? Kings Cross? Next to the Google building? We were trying to choose an urban space and ended up with Victoria Square, but I think the idea of it being a truly public space is quite important.”

figs.v

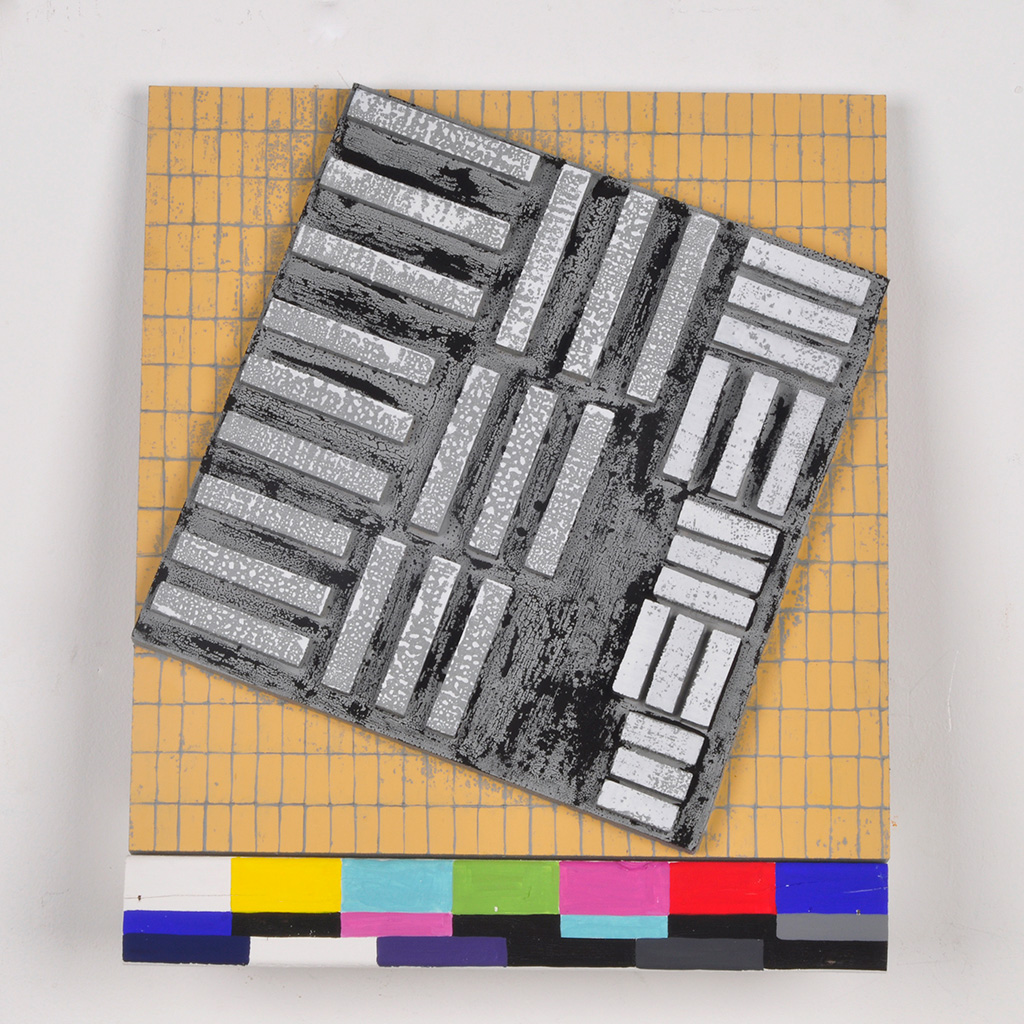

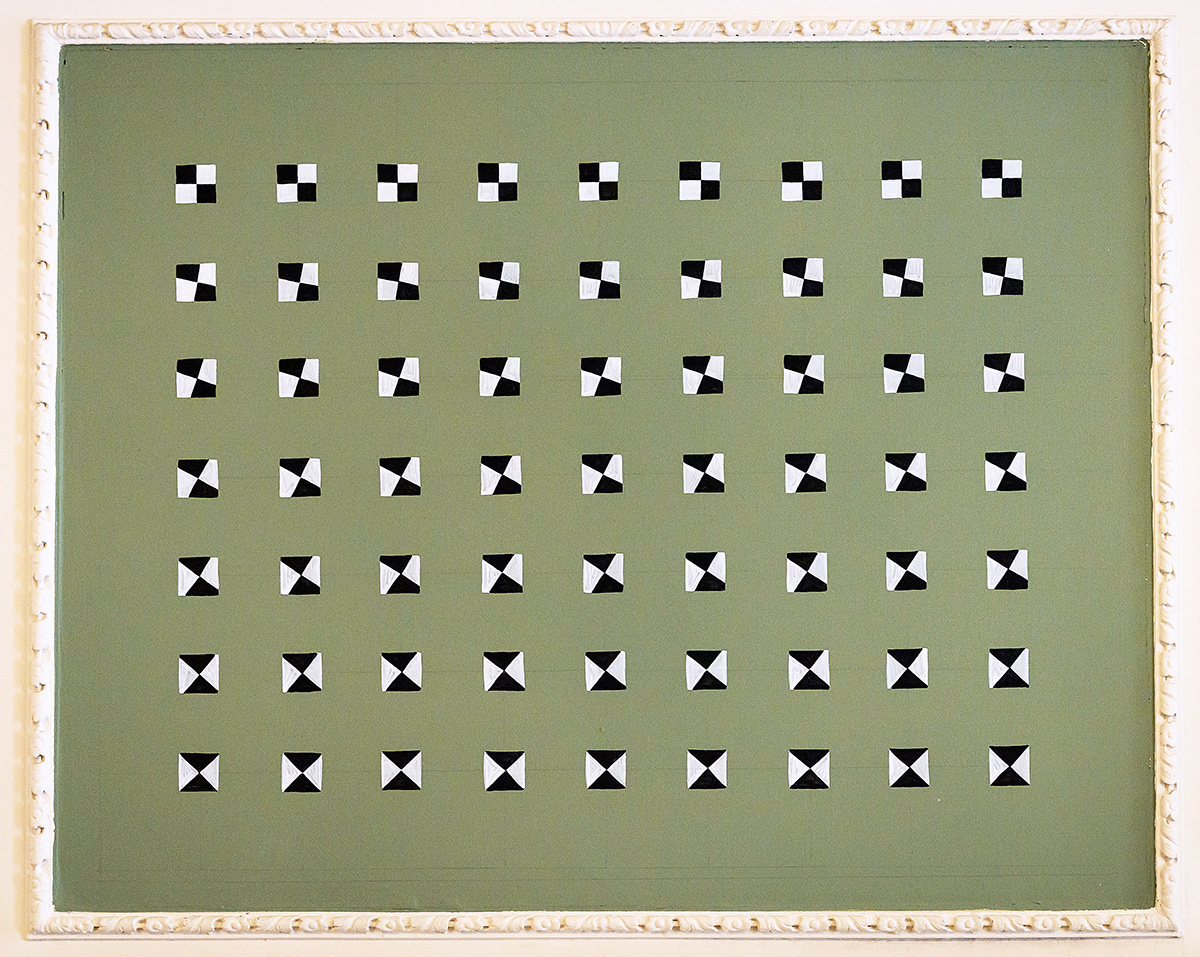

The sculpture also acts as a graphical form, as other works have, touching back on the relationship between logomark or glypth and abstract artwork. This is the case with a series of works from 2012-13, each showing a rotated grid of rigid geometric forms. They could be mappings of modernist housing, or the underlying grid of semiconductors, maybe a QR code. The mind wonders as it looks at the arrangements. They are in fact aerial calibrations, vast interventions in desert landscapes used for surveillance and calibration of cameras from satellites and aircraft.

The desert landscapes in which these land-art-like symbols sit is of interest to Dossos, who lived in Kuwait when the second Iraq war began, an event she describes as being “massively formative for me, politically. In Kuwait the desert was a place you didn’t go, because it was full of mines from the first Gulf War. So not only was stuff going up through Kuwait into Iraq at the time, but it wasn't really a space you could go and spend time in any way, because it was dangerous.”

As well as a space of potential physical danger, the desert has been a figurative stand in for otherness from a western and predominantly white canon. A uniform aesthetic into which presumption, colonial- and post-colonialism, shorthand narratives, and racialised stereotyping can be loaded into a heady mix of exoticness.

“When I studied Ottoman art and architecture [I was interested in a] post-colonial approach to reading Orientalist architecture in a western context, so it was very much a critical view of how, for example, mosque architecture became pavilions and spaces to have tea. That’s always fascinated me - there was a power structure involved in doing this that needed to be spoken about. The desert has always been this kind of space of incredible imagination for the West, and for many writers and artists in particular.”

figs.vi

One artist is Richard Dadd, 19th century British watercolourist who travelled through the lands west of Iraq as artist-accompaniment Welshman Sir Thomas Phillips on his Grand Tour through Venice, Greece and Egypt. On the trip, Dadd had a breakdown, returned to England and tragically murdered his father before being locked up in Bethlem Hospital, where he continued to paint.

Dossos’ mural installation Komt Hier Aan Deze Gele Vlaktes (Come Unto These Yellow Sands) (2015) takes its name from an 1842 Dadd painting, in turn drawing its title from Ariel’s song in Act I, Scene II of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. It was a work for Probe, a physical 6.6m² space only viewable by the public online as a Dutch project running from 2008-2019.

“I wanted to think more about the idea of an interior desert, in the Netherlands there is actually a desert, a lot of sand that came from a glacier is right in the centre of the Netherlenads as a desert. I wanted to say that sometimes you have to stop looking for the other on the outside and actually look for the desert within, and for the otherness within yourself - instead of the exoticisation of the other, or the desert of Arabia, we need to examine these things that exist within ourselves. That’s why it’s also referencing Dadd, somebody who really looked for these interior landscapes with an incredible imagination that came from within himself - he also spent time in Egypt and there is a whole Orientalist conversation to be had about what happened to him before he killed his father.”

figs.vii

The duality of symbolism in landscape and nature runs through Dossos’ work. Another project, Imagine a Palm Tree (2016) explores just this, through the history of palm trees in Athens. The artist had moved to Athens the previous year, and heard a story told repeatedly with slight variations which spoke about the city once being covered in palm trees before being removed to make the city appear more European and less Orientalwith only a few remaining in the botanical gardens and surrounding churches.

“Palm trees used to exist in Athens and had done for centuries, and when the Ottomans were kicked out and Athens specifically became the centre of the new independent Greece that was very much framed around a kind of northern European notion of what Hellenic culture should look like, all the palm trees were basically cut down because they made it look to African or exotic, or oriental. They were only brought back for the [2004] Olympic Games, when they had a completely different meaning of luxury and summer holidays, so the whole meaning of this tree had changed.”

Dossos used the motif of the palm tree within the café of the Benaki Museum’s Islamic Art Collection, showing the tree, its leaves, and roots penetrating a CCTV infused sky and metro-excavated depths as a continuity, speaking to all versions of place, including those not visible at first glance.

figs.viii

For A Year Without Movement (2017), Dossos made visible more unseen urbanity. The House of Saint Barnabas - a Grade I listed building, ethical members club, and homeless charity - found itself directly above the subterranean digging for London’s Crossrail railway line. The artist created a series of site specific wall paintings throughout the panelled interior, pulling symbols of Crossrail into the building above, itself being precariously observed for movement and subsidence as engineering took place below.

“Crossrail is a massive undertaking, churning up earth underneath, doing something very profound to the city. The very ground these buildings are standing on is affected and there is a fragility of the structures that needs to be recognised, especially somewhere like Soho – these buildings are so familiar, they seem so solid, and so present.”

Dossos is inquiring about the perceived strength of our architectures – and the institutions, social contracts, economies, and structures which shape the city. She used to walk past the House of Saint Barnabas as a child, and growing older began to understand its history as a space of security and safety, especially for women, and through this how the very ecosystem of the city is as precarious as the heritage which holds it.

“The systems are fragile and the building is fragile, because of this other kind of system underneath. But if we can make visible some of those systems perhaps it give us an understanding of what's happening. The intention is to try and bring about a conversation about what's happening and how these things affect each other, how that digging and creation of new links can undermine a building, but also other kinds of social structures as well.”

The construction of Crossrail, as with all urban infrastructure, will see tectonic plates of value, cost of living, regeneration, and development shift, and with that who can call London home, and who has none.

figs.ix

This touches on Dossos’ next project, and (on a personal level at least) the most personal and important – a house for her family: “My partner and I are planning to self-build our own house over the next few years, using the Walter Segal method, mixing it with more Greek vernacular architectures and using local materials. I think it's an interesting progression for me to go from not just painting the wall but making the wall - making the structure and understanding it fundamentally. I don't want to take the structure for granted any more, but to really think about what it means to make that structure and the volumes of it as well.”

fig.x

Navine G. Dossos (1982, London) is a visual artist working between London & Athens. Her interests include Orientalism in the digital realm, geometry as information and decoration, image calibration, & aniconism in contemporary culture. She has developed a form of geometric abstraction that merges the traditional aniconism of Islamic art with the algorithmic nature of the interconnected world we live in. This is not the formal abstraction we understand from the western history of art, but something essentially informational, & committed to investigation & communication. Dossos studied History of Art at Cambridge University, Arabic at Kuwait University, Islamic Art at the Prince’s School of Traditional Art in London, & holds an MA in Fine Art from Chelsea College of Art & Design, London.

www.khandossos.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, & educator interested in cities, architecture, & culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, & Icon. He teaches history & theory at UCL Bartlett & Greenwich University, & is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

images

fig.i

Ta Nea Xysta (2021), photograph

© Yiannis Hadjiaslanis

figs.ii-iii

Ta Nea Xysta (2021), photograph © Yiannis Hadjiaslanis. Image of artwork being painted

©

Emilios Haralambous / Nysos Vasilopoulos for AB7.

fig.iv BLE (2021), inkjet print

on fine art paper, image

©

Navine G. Dossos in collaboration with Dimitris Papoutsakis.

figs.v

Aerial Calibration Horizontal (2012),

Aerial Calibration Vertical (2012), &

Aerial Calibration Square (2013), all oil & gouache on wood, © Navine G. Dossos

figs.vi

Komt Hier Aan Deze Gele Vlaktes (Come Unto These Yellow Sands) (2015) © Navine G. Dossos. For more information see Project Probe at: www.projectprobe.net/probe/30/8

fig.vii Imagine a Palm Tree (2016). Photographs ©

Yiannis Hadjiaslanis.

fig.viii-ix

Navine G. Dossos at Athens Biennale 7. Photograph © Emilios Haralambous / Nysos Vasilopoulos for AB7

publication date

23 February 2022

tags

Athens, Athens Bienniale, CCTV, Communication, Crossrail, Decoration, Desert, Geometry, House of Saint Barnabas, Murals, Navine Dossos, Kuwait, Landscape, Language, Nature, Orientalism, Ottoman, Painting, Palm Tree, Render, Sculpture, Walter Segal, Surveillance

figs.ii-iii Ta Nea Xysta (2021), photograph © Yiannis Hadjiaslanis. Image of artwork being painted © Emilios Haralambous / Nysos Vasilopoulos for AB7.

fig.iv BLE (2021), inkjet print on fine art paper, image © Navine G. Dossos in collaboration with Dimitris Papoutsakis.

figs.v Aerial Calibration Horizontal (2012), Aerial Calibration Vertical (2012), & Aerial Calibration Square (2013), all oil & gouache on wood, © Navine G. Dossos

figs.vi Komt Hier Aan Deze Gele Vlaktes (Come Unto These Yellow Sands) (2015) © Navine G. Dossos. For more information see Project Probe at: www.projectprobe.net/probe/30/8

fig.vii Imagine a Palm Tree (2016). Photographs © Yiannis Hadjiaslanis.

fig.viii-ix Navine G. Dossos at Athens Biennale 7. Photograph © Emilios Haralambous / Nysos Vasilopoulos for AB7

publication date

23 February 2022

tags

Athens, Athens Bienniale, CCTV, Communication, Crossrail, Decoration, Desert, Geometry, House of Saint Barnabas, Murals, Navine Dossos, Kuwait, Landscape, Language, Nature, Orientalism, Ottoman, Painting, Palm Tree, Render, Sculpture, Walter Segal, Surveillance