How Uzbekistan’s incredible Sun Heliocomplex brought light

to Venice Biennale

One hour outside Uzbekistan’s capital city, Tashkent, is the

incredible Sun Heliocomplex, a late-Soviet-era scientific experiment –

architecture at a giant scale to reflect the sun beams to reach a temperature half

that of the sun’s surface. Will Jennings visited, then saw how the complex was presented

at the Uzbekistan pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale, one of the national

highlights of the edition.

Architecture comes in all shapes and sizes. But, amongst

that variation there are general typologies and aesthetic forms that repeat.

However much a building is dressed up in style, usually the programme and

purpose of a building is the main prerogative. Hospitals may not all look quite

the same, but their function requires a certain form. An art gallery may have

its own specific visual identity, but the arrangement of space and light to

serve the display of art rarely changes drastically.

Then a building turns up that looks like no other, because its programme and purpose is unique, requiring a bespoke architectural language and appearance. This is the case with the Sun Heliocomplex an hour’s drive outside Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Constructed between 1981 and 1987 at 1,200 metres above sea level, the building has a singular purpose: to reflect the rays of the sun into a small chamber, within which temperatures can reach 3000°C, in order to study the behaviour of newly designed materials.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Architecturally, this is no standard laboratory. Visible on the approach road from some distance as a large monolithic form standing proud on rocky foothills, two huge concentric yellow circles decorating a facade formed of a horizontal rhythm interrupted by a central tower pushing into the sky. It is an intriguing site, but only a foreshadow for the extraordinary arrangement of buildings and ancillary structures that forms the complex.

A series of 62 highly-reflective square mirrors are arranged over eight terraces. This graphic grid of south-facing reflectors can be programmed to follow the path of the sun, accurately reflecting its rays towards the largest building of the complex, the monolith that could be seen from surrounding plains. The other side of the block to the concentric circles faces the mirrored terraces, a concave mirrored surface of 10,700 mirrored tiles that receive the reflected sun rays. They too reflect the beams, but tightening the focus through a small diameter of 30cm into a central furnace where temperatures reaching half that of the surface of the sun can be reached.

![]()

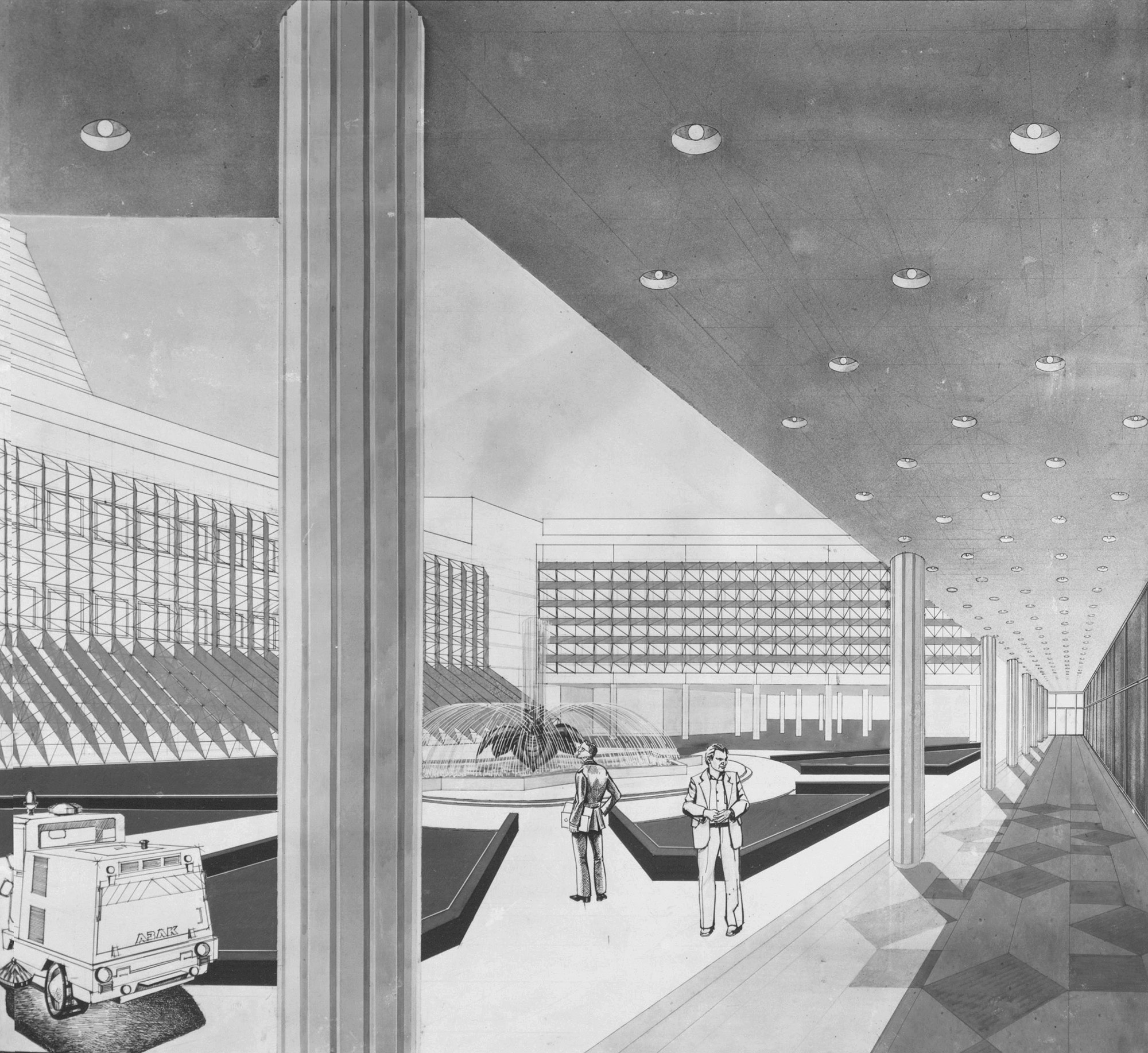

fig.iv

Still operating following the collapse of the Soviet Union shortly after its completion, and now called the Sun Institute of Material Science (and sometimes referred to as the Big Solar Furnace), recessed.space visited the Heliocomplex on a trip supported by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF) who have included the structure on a list of ten buildings presented to UNESCO to consider listing as world heritage for their unique architectural value as Tashkent Modernism. The Heliocomplex is perhaps an outlier in the list, with the other nine all found in the centre of Tashkent and speaking more closely to the specific identified Tashkent Modernism vernacular, softening Soviet order and principles with ornamentation, detail, and geometric pattern that speak to historic Uzbek and Islamic design.

There are, however, moments of such aesthetic within the 30,000 square metres of laboratory and offices within the complex designed by Viktor Zakharov, including ceramic panelling and a spectacular chandelier – titled Parade of Planets – by Latvian artist Irena Lipene. There is a wonderful coming together of scientific programme and applied arts across the complex, something recognised by Milan-based Grace architects, led by Ekaterina Golovatyuk and Giacomo Cantoni, who lead the preservation strategy for not only the Heliocomplex but the wider body of Tashkent Modernism.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The ACDF and Grace architects are also behind the Uzbekistan national pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale of Architecture, one of the most successful national offerings with a delightfully arranged focus upon the Heliocomplex. Titled A Matter of Radiance, it is an airy presentation that does in curation what so many Biennale pavilions that try to cram in vast amounts of information into models, long wall texts, and dense theory, Grace’s curation has clarity and joy.

A number of fragments from the Heliocomplex are spread across the Uzbek Arsenale hall. One of the rectangular heliostat mirrors stands as a sculpture when detached from its context, but the engineering and intelligence of the mirrors and framework are richly seen. Crossing the breadth of the space, and nearly filling the height, is a geometric framework façade sunscreen from the office buildings.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A 1984 painting by Vladimir Burmakin of the Leaders of Modern Science in Uzbekistan hangs on the wall watching over and a control room table sits in the centre of it all with an arrangement of smaller material elements spread across. Irena Lipene’s Parade of Planets chandelier glows brightly, and will return to Parkent resplendent with repairs by Venetian glassworkers. Photographs by Armin Linke (who we previously featured, see 00062) capture details from the Heliocomplex in his inimitable style.

But there is more than aesthetic presentation and creating sculpture from architectural fragments. A model of the complex is presented to help visitors understand the spatial arrangements, there is a long section of the site on the wall to explain the process of the sun’s rays, and a new publication explores the history of the scientific architectural experiment with interviews of those involved working or running the centre alongside conceptual underpinning for how the solar project could feed into new thinking for energy sustainability.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Heliocomplex is located where it is following a Soviet search for the best location for such a scientific project. It sits on a single rock outcrop, meaning any earthquake tremors don’t lead to minute movement of the mirrors while the location receives the most annual sunlight across all the Soviet regions. It does mean that even though it does open to the public for viewing, the site is not on most tourist or architectural trails, with most visitors following the Silk Road towards ancient cities including Samarkland and Khiva. It is an incredible, enormous complex, and in a Biennale context there can be the urge for curators to in some way squeeze the building into the Pavilion space as if to give visitors as much of a similar experience as possible.

Here, Grace and ACDF take a richer and more intelligent approach, and in doing so extract details and fragments that communicate the true essence of the site without overloading the visitor with too much information. The exhibit stands as a cleverly formed sculptural installation as well as a tantalising tease into the rich history and possible future of the Heliocomplex. If you can, do go to Parkent to experience it in all its glory, but if you can’t get to Uzbekistan any time soon then a trip to Venice to see A Matter of Radiance is a great alternative.

Then a building turns up that looks like no other, because its programme and purpose is unique, requiring a bespoke architectural language and appearance. This is the case with the Sun Heliocomplex an hour’s drive outside Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Constructed between 1981 and 1987 at 1,200 metres above sea level, the building has a singular purpose: to reflect the rays of the sun into a small chamber, within which temperatures can reach 3000°C, in order to study the behaviour of newly designed materials.

figs.i-iii

Architecturally, this is no standard laboratory. Visible on the approach road from some distance as a large monolithic form standing proud on rocky foothills, two huge concentric yellow circles decorating a facade formed of a horizontal rhythm interrupted by a central tower pushing into the sky. It is an intriguing site, but only a foreshadow for the extraordinary arrangement of buildings and ancillary structures that forms the complex.

A series of 62 highly-reflective square mirrors are arranged over eight terraces. This graphic grid of south-facing reflectors can be programmed to follow the path of the sun, accurately reflecting its rays towards the largest building of the complex, the monolith that could be seen from surrounding plains. The other side of the block to the concentric circles faces the mirrored terraces, a concave mirrored surface of 10,700 mirrored tiles that receive the reflected sun rays. They too reflect the beams, but tightening the focus through a small diameter of 30cm into a central furnace where temperatures reaching half that of the surface of the sun can be reached.

fig.iv

Still operating following the collapse of the Soviet Union shortly after its completion, and now called the Sun Institute of Material Science (and sometimes referred to as the Big Solar Furnace), recessed.space visited the Heliocomplex on a trip supported by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF) who have included the structure on a list of ten buildings presented to UNESCO to consider listing as world heritage for their unique architectural value as Tashkent Modernism. The Heliocomplex is perhaps an outlier in the list, with the other nine all found in the centre of Tashkent and speaking more closely to the specific identified Tashkent Modernism vernacular, softening Soviet order and principles with ornamentation, detail, and geometric pattern that speak to historic Uzbek and Islamic design.

There are, however, moments of such aesthetic within the 30,000 square metres of laboratory and offices within the complex designed by Viktor Zakharov, including ceramic panelling and a spectacular chandelier – titled Parade of Planets – by Latvian artist Irena Lipene. There is a wonderful coming together of scientific programme and applied arts across the complex, something recognised by Milan-based Grace architects, led by Ekaterina Golovatyuk and Giacomo Cantoni, who lead the preservation strategy for not only the Heliocomplex but the wider body of Tashkent Modernism.

figs.v-xi

The ACDF and Grace architects are also behind the Uzbekistan national pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale of Architecture, one of the most successful national offerings with a delightfully arranged focus upon the Heliocomplex. Titled A Matter of Radiance, it is an airy presentation that does in curation what so many Biennale pavilions that try to cram in vast amounts of information into models, long wall texts, and dense theory, Grace’s curation has clarity and joy.

A number of fragments from the Heliocomplex are spread across the Uzbek Arsenale hall. One of the rectangular heliostat mirrors stands as a sculpture when detached from its context, but the engineering and intelligence of the mirrors and framework are richly seen. Crossing the breadth of the space, and nearly filling the height, is a geometric framework façade sunscreen from the office buildings.

figs.xii-xvii

A 1984 painting by Vladimir Burmakin of the Leaders of Modern Science in Uzbekistan hangs on the wall watching over and a control room table sits in the centre of it all with an arrangement of smaller material elements spread across. Irena Lipene’s Parade of Planets chandelier glows brightly, and will return to Parkent resplendent with repairs by Venetian glassworkers. Photographs by Armin Linke (who we previously featured, see 00062) capture details from the Heliocomplex in his inimitable style.

But there is more than aesthetic presentation and creating sculpture from architectural fragments. A model of the complex is presented to help visitors understand the spatial arrangements, there is a long section of the site on the wall to explain the process of the sun’s rays, and a new publication explores the history of the scientific architectural experiment with interviews of those involved working or running the centre alongside conceptual underpinning for how the solar project could feed into new thinking for energy sustainability.

figs.xviii-xx

The Heliocomplex is located where it is following a Soviet search for the best location for such a scientific project. It sits on a single rock outcrop, meaning any earthquake tremors don’t lead to minute movement of the mirrors while the location receives the most annual sunlight across all the Soviet regions. It does mean that even though it does open to the public for viewing, the site is not on most tourist or architectural trails, with most visitors following the Silk Road towards ancient cities including Samarkland and Khiva. It is an incredible, enormous complex, and in a Biennale context there can be the urge for curators to in some way squeeze the building into the Pavilion space as if to give visitors as much of a similar experience as possible.

Here, Grace and ACDF take a richer and more intelligent approach, and in doing so extract details and fragments that communicate the true essence of the site without overloading the visitor with too much information. The exhibit stands as a cleverly formed sculptural installation as well as a tantalising tease into the rich history and possible future of the Heliocomplex. If you can, do go to Parkent to experience it in all its glory, but if you can’t get to Uzbekistan any time soon then a trip to Venice to see A Matter of Radiance is a great alternative.

figs.xxii-xxvi

The Uzbekistan Art & Culture Development Foundation (ACDF)

preserves, promotes & nurtures Uzbekistan’s heritage, arts & culture.

Positioned at the forefront of Uzbekistan’s cultural development, ACDF is

committed to fostering the cultural ecosystem of the country, driving the

creative economy & providing opportunities for practitioners on a local,

regional & global stage. ACDF believes that culture & heritage are

vital in shaping society, uniting communities, bridging generations & facilitating

cross-cultural conversations.

ACDF has successfully led the fourth edition of the World

Conference on Creative Economy (WCCE) (2–4 October 2024) in Tashkent & the

inaugural Aral Culture Summit (4–6 April 2025) in Nukus, Karakalpakstan. The

Foundation currently spearheads Uzbekistan’s participation in Expo 2025 Osaka,

Kansai, Japan (April–October 2025), the renovation of the Centre for

Contemporary Art in Tashkent, the construction of the new State Museum of Arts

designed by Tadao Ando & the restoration & partial reconstruction of

the Palace of the Grand Duke of Romanov. ACDF has also launched “Tashkent

Modernism XX/XXI”, an ongoing research project documenting & protecting the

city's modernist architecture, highlighted by two significant publications in

collaboration with Rizzoli New York (published in November 2024) & Lars

Müller Publishers. In Bukhara, ACDF is launching the first Bukhara Biennial in

September 2025.

www.acdf.uz

Grace is an international studio of architecture,

urbanism & research, based in Milan. It was founded by Ekaterina Golovatyuk

& Giacomo Cantoni, whose past work experience includes a long-term

collaboration with OMA/AMO, focusing on cultural & research projects in

Europe & Hong Kong.

Preservation is a central theme of the studio’s work, with

particular focus on 20th-century heritage. As well as several individual

projects in Central Asia, Grace’s current collaboration with the Uzbekistan Art

& Culture Development Foundation, Politecnico di Milano & a group of

local & international researchers to revise the legal framework & develop

strategies to preserve 21 modernist buildings in Tashkent has led to the

forming of a particular expertise & the establishment of a critical

position on the subject, beyond the current ideological & market-driven

paradigm.

www.grace.eu

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist & educator interested in cities, architecture & culture. He has written for Wallpaper*, Canvas, The Architect’s Newspaper, RIBA Journal, Icon, Art Monthly & more. He teaches history & theory at UCL Bartlett & is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

Preservation is a central theme of the studio’s work, with particular focus on 20th-century heritage. As well as several individual projects in Central Asia, Grace’s current collaboration with the Uzbekistan Art & Culture Development Foundation, Politecnico di Milano & a group of local & international researchers to revise the legal framework & develop strategies to preserve 21 modernist buildings in Tashkent has led to the forming of a particular expertise & the establishment of a critical position on the subject, beyond the current ideological & market-driven paradigm.

www.grace.eu