Tolia Astakhishvili’s architectural excavation in Venice changes

the way artists use the city

The new home of the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation in Venice has opened, but it is markedly different from other exhibition spaces in the city. Supported by curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, artist

Tolia Astakhishvili has excavated the architectural history of the Dorsoduro building to create an uncanny, haunting, poetic exploration of the space between de- & re-construction.

Whenever a Venice palazzo comes up for sale, the chances are

that the eventual buyer will be an art foundation or an individual looking to

start one up. This is the case with the recent purchase of the 15th

century ornate Palazzo Pisani Moretta by Belgian fashion designer Dries Van

Noten for an estimated €36m. Overlooking the Grand Canal, Van Noten plans to

turn the Baroque and Gothic palazzo into a centre of artisanship and craft,

following a model that can be found in countless grand houses and deconsecrated

churches across La Serenissima.

It's a model almost perfectly set up for rich artistic presentations. The glowing, romantic, and rich art object carefully positioned to juxtapose with the classical setting, a view onto the water, or in eyeshot of historic artwork, sculpture, or furniture. It can be sublime. It can, however, also be boring. Venice is not short of ornate interior and over Biennale season there is similarly no shortage of incredibly expensive contemporary art objects juxtaposed into these interiors. To trawl all the spaces, being repeatedly hammered in the face by luxurious historical and modern art objects can be easy on the eye, but repetitive and eventually less exciting and interesting. A new opening turns this approach completely on its head, and in doing so brings to Venice a more playful, architecturally responsive, and cutting way to present work than the city currently offers.

![]()

![]()

![]()

to love and devour is an exhibition curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist that marks the opening of the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation in the floating city. At once a curated show and an artwork in itself, it distorts and interjects itself into the stripped back archi

That playing has largely been carried out by Georgian artist Tolia Astakhishvili who lived and worked in the building for months before the Foundation’s opening. Over that time, she removed surfaces, chopped out partition walls, entangled and disentangled pipework and ducts, and generally surgically fucked up the guts of the place in a way that leaves the resultant shell as an uncanny site between dereliction and rebirth.

![]()

![]()

![]()

This is not by accident. Italian collector and arts patron Nicoletta Fiorucci told recessed.space that she had wanted to expand her foundation, which focuses on emerging artists, into Venice but did not want to follow that well-trodden path of singular art objects sitting in a grand palazzo setting. Instead of buying herself a residence, she rents (a still extremely grand) floor in a Grand Canal palazzo, and instead decided to put capital investment into the Foundation’s building. She wants it to grow, but does not completely know in what way yet, but knew that she wanted artists to be central to the reading and evolution of the building rather than simply being presented with a completed, perfected, gallery context.

As all architects know, to understand how a project might progress in the future it is important to strip it back both physically and conceptually, to understand its physicality but also its history, stories, context, and feeling. The Dorsoduro building has interesting histories to unravel, even beyond being owned by the artist Ettore Tito in the 1920s. The property, comprising shops and merchant spaces on the ground floor with a series of large residential rooms above, had been owned by a school for orphaned girls, connected to the Priory of Saint Agnese, which relied on the property’s rental income. Repeatedly suffering from decay and leaks, not to mention theft of windows, doors, and other architectural features, the school in 1793 set about overhauling the properties to again benefit from the rent.

Again, however, it started to fall apart. By the time Ettore Tito, who resided next door, bought it in 1923 it had again fallen into an uninhabitable and ruinous condition. Tito began to renovate the building and add to it, including with a painter’s studio. In 1937, architect Angelo Scattolin further remodelled the building, with 1973 improvements adding further layers of architectural strata.

Consequently, when Nicoletta Fiorucci took ownership, the building was not easy to read as a coherent whole. Keen to use culture to shape as well as occupy its next incarnation, Fiorucci invited Astakhishvili to physically and conceptually explore these architectural ghosts, her resultant project at first reading as a dishevelled form of abandonment, but slowly revealing potential pasts and futures.

![]()

![]()

![]()

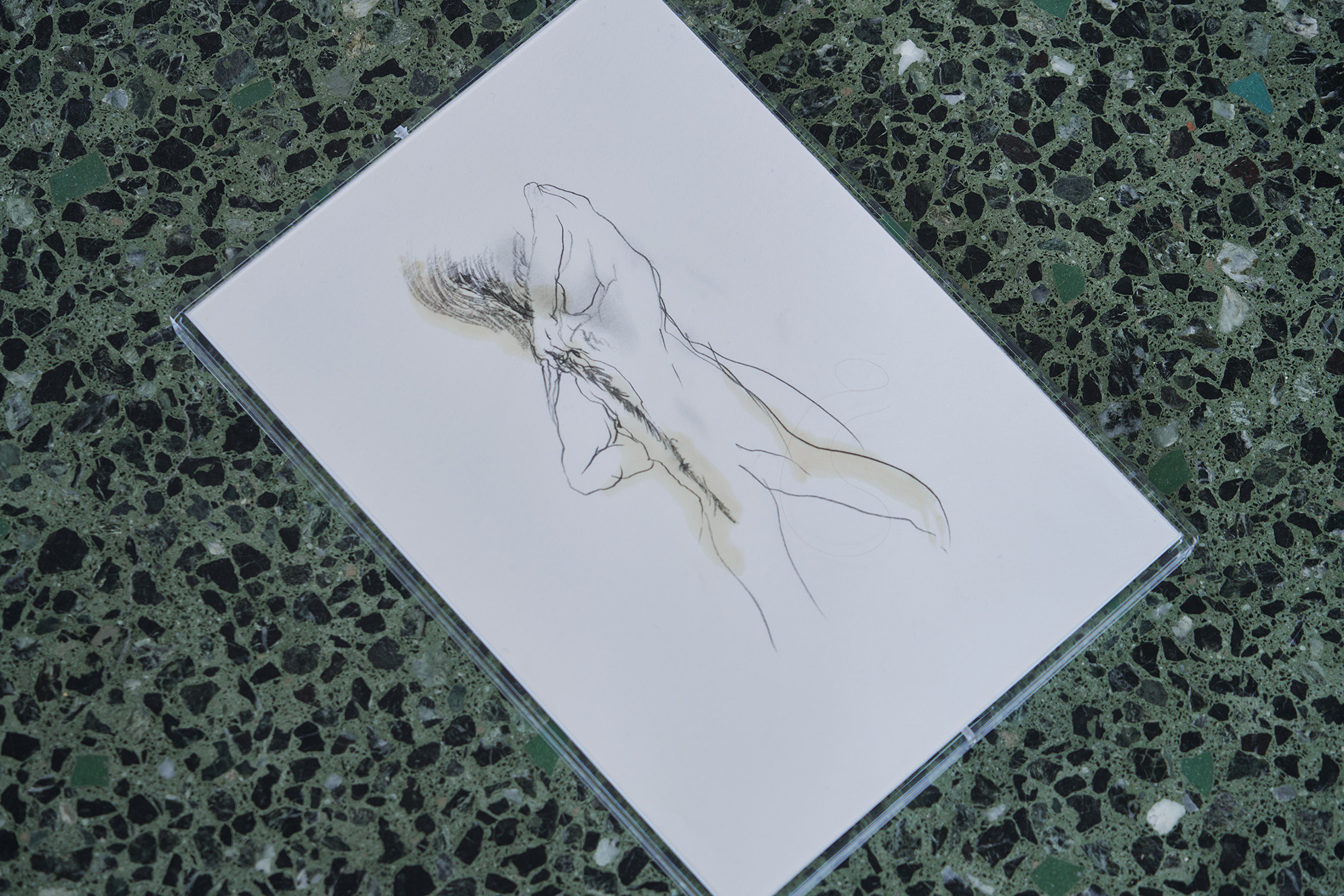

She has done this, with the support of Obrist, and by inviting other artists into a conversation with the building. Many of those works relate to the practice of drawing, making connection perhaps between the act of impermanent sketching and the fact that however solid architecture seems it is but a momentary drawing of an idea, one which will change in unknown ways. As drawing contains within it a looseness of being, so too does Astakhishvili’s transformation of the built context. If a drawing is a process of addition and removal, of layering and shifting weight on the page, the artist’s approach to reforming the architecture is similarly sketched.

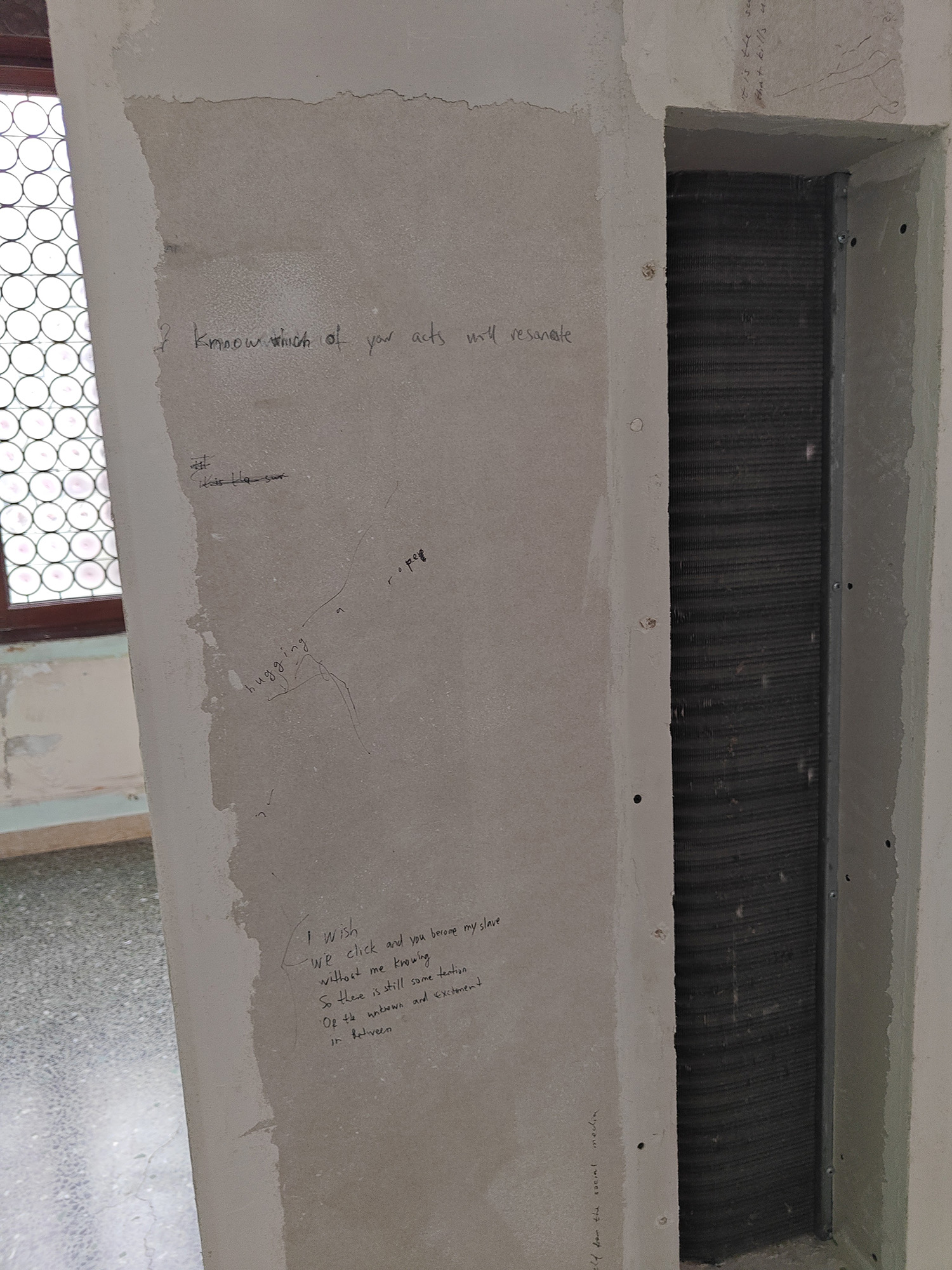

Lines across walls and ceilings track where walls once were, or perhaps will be. Text and marks on the wall might belong to previous occupants, they may have been added by the artist or her friends, or perhaps they sit there as construction notations for future builders to draw meaning from. Spaces have been stripped back, some infilled. Surfaces have been added, openings formed, material scraped, debris piled.

Toilets and sinks seem to have been relocated, suggesting an unfixed internal system and further destabilising the very truths one expects of architectural fundamentals. Pipework that was once subsumed into walls and floors now stands free, sculpturally centred in a room and asking questions around whether it was relocated or if the fabric around it was meticulously removed.

![]()

![]()

![]()

In the unravelling, aesthetic choices from the mid-19th century rub up against more historic features. Where we normally see the skin of architecture, from a single organised moment, here strata and histories are revealed and reordered. A compression of indeterminable times creates a version of the place that somehow straddles its entire life, from the 15th to 21st centuries.

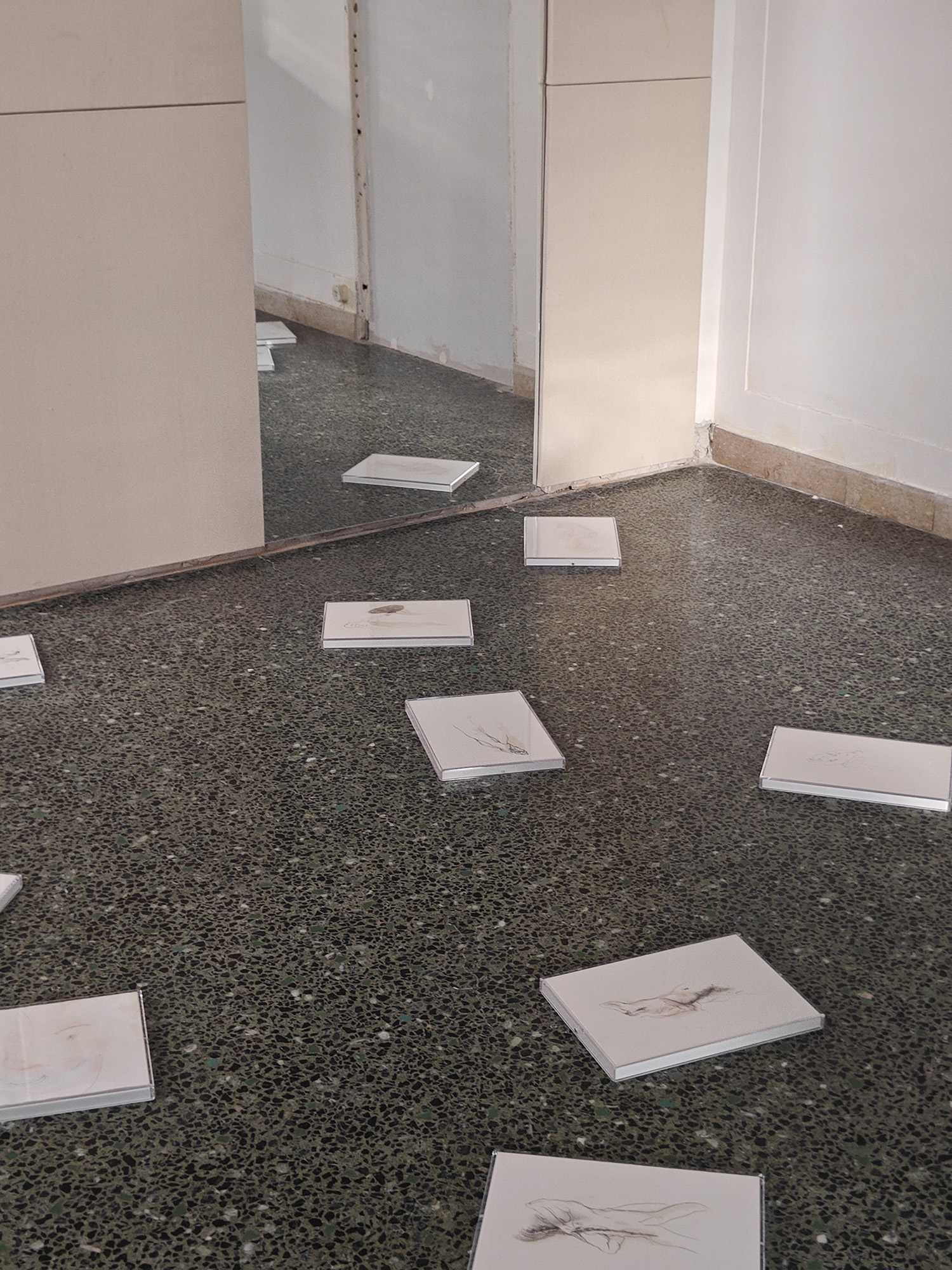

This is an approach that Astakhishvili has used before, though more often in a white-walled gallery space, turning artworld perfection into a construction site space of betweenness. Here, with the artist working onto and into a building lost to ruin and ahead of it becoming a (re)construction site, the artist had opportunity to more deeply play with the methodology. Then, into it all are 47 artworks, some presented with absolute clarity – on plinths or in frames – and others disappearing into the atmosphere and shadows of the place.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Artworks by Astakhishvili carry other architectural memories. Beautiful neighbour (2024) contains a 3d-printed architectural model in collage with drawing on a slapdash plaster backing. taste (snoring and the sound of pigeons) (2025) sits as a monolith in the ground floor, cutlery and found objects embedded into what reads as a concrete mass filling a room. I love seeing myself through the eyes of others (2025) is a vast lightbox of plastic covered in paint and photos, a light inside where visitors can’t go, an unreachable room within a room.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Works by others are positioned within the building as if to suggest they had always been there, perhaps uncovered by artistic excavation. A work made with Dylan Peirce appropriates a dismantled ventilation unit and drywall plaster. Thea Djorjadze’s sculptural work is formed of eight twisted and torn pieces of aluminium which could easily be read as construction site castoffs. Astakhishvili and James Richards collaborated to create Our Friends In the Audience (2024), a marouflage on canvas print, a portrait of a young girl solemnly staring back – a hauntological reach, perhaps, to the girls of the school that once owned this building.

One work, Suddenly the world became loud II, made last year with Zurab Astakhishvili, the artist’s father, reads like a cardboard tower block encased in Perspex, as if a preservation, protection, or prison. Shortly after the opening of to love and devour, Zurab passed away, ending a familial artistic dialogue. The work now takes on other meanings, standing as a self-crafted memorial, just as the building surrounding it also contains palimpsests of lives lived, loves lost, stories made and remade, some visible, some secreted.

![]()

Many works may not be noticed. Photos left on ledges, scribbles into the architectural marginalia, and print covering windows. The project relies on natural light, further creating the mood and sense of timelessness. Altogether, it’s a gesamtkunstwerk in which architecture and artwork combine into some new space between. And in a city punctuated by annual art and architecture Biennials, resplendent in the grand, gaudy, and sublime, it’s a welcome disruption and exciting start to what the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation and building may evolve to become.

It's a model almost perfectly set up for rich artistic presentations. The glowing, romantic, and rich art object carefully positioned to juxtapose with the classical setting, a view onto the water, or in eyeshot of historic artwork, sculpture, or furniture. It can be sublime. It can, however, also be boring. Venice is not short of ornate interior and over Biennale season there is similarly no shortage of incredibly expensive contemporary art objects juxtaposed into these interiors. To trawl all the spaces, being repeatedly hammered in the face by luxurious historical and modern art objects can be easy on the eye, but repetitive and eventually less exciting and interesting. A new opening turns this approach completely on its head, and in doing so brings to Venice a more playful, architecturally responsive, and cutting way to present work than the city currently offers.

figs.i-iii

to love and devour is an exhibition curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist that marks the opening of the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation in the floating city. At once a curated show and an artwork in itself, it distorts and interjects itself into the stripped back archi

That playing has largely been carried out by Georgian artist Tolia Astakhishvili who lived and worked in the building for months before the Foundation’s opening. Over that time, she removed surfaces, chopped out partition walls, entangled and disentangled pipework and ducts, and generally surgically fucked up the guts of the place in a way that leaves the resultant shell as an uncanny site between dereliction and rebirth.

figs.iv-vi

This is not by accident. Italian collector and arts patron Nicoletta Fiorucci told recessed.space that she had wanted to expand her foundation, which focuses on emerging artists, into Venice but did not want to follow that well-trodden path of singular art objects sitting in a grand palazzo setting. Instead of buying herself a residence, she rents (a still extremely grand) floor in a Grand Canal palazzo, and instead decided to put capital investment into the Foundation’s building. She wants it to grow, but does not completely know in what way yet, but knew that she wanted artists to be central to the reading and evolution of the building rather than simply being presented with a completed, perfected, gallery context.

As all architects know, to understand how a project might progress in the future it is important to strip it back both physically and conceptually, to understand its physicality but also its history, stories, context, and feeling. The Dorsoduro building has interesting histories to unravel, even beyond being owned by the artist Ettore Tito in the 1920s. The property, comprising shops and merchant spaces on the ground floor with a series of large residential rooms above, had been owned by a school for orphaned girls, connected to the Priory of Saint Agnese, which relied on the property’s rental income. Repeatedly suffering from decay and leaks, not to mention theft of windows, doors, and other architectural features, the school in 1793 set about overhauling the properties to again benefit from the rent.

Again, however, it started to fall apart. By the time Ettore Tito, who resided next door, bought it in 1923 it had again fallen into an uninhabitable and ruinous condition. Tito began to renovate the building and add to it, including with a painter’s studio. In 1937, architect Angelo Scattolin further remodelled the building, with 1973 improvements adding further layers of architectural strata.

Consequently, when Nicoletta Fiorucci took ownership, the building was not easy to read as a coherent whole. Keen to use culture to shape as well as occupy its next incarnation, Fiorucci invited Astakhishvili to physically and conceptually explore these architectural ghosts, her resultant project at first reading as a dishevelled form of abandonment, but slowly revealing potential pasts and futures.

figs.vii-ix

She has done this, with the support of Obrist, and by inviting other artists into a conversation with the building. Many of those works relate to the practice of drawing, making connection perhaps between the act of impermanent sketching and the fact that however solid architecture seems it is but a momentary drawing of an idea, one which will change in unknown ways. As drawing contains within it a looseness of being, so too does Astakhishvili’s transformation of the built context. If a drawing is a process of addition and removal, of layering and shifting weight on the page, the artist’s approach to reforming the architecture is similarly sketched.

Lines across walls and ceilings track where walls once were, or perhaps will be. Text and marks on the wall might belong to previous occupants, they may have been added by the artist or her friends, or perhaps they sit there as construction notations for future builders to draw meaning from. Spaces have been stripped back, some infilled. Surfaces have been added, openings formed, material scraped, debris piled.

Toilets and sinks seem to have been relocated, suggesting an unfixed internal system and further destabilising the very truths one expects of architectural fundamentals. Pipework that was once subsumed into walls and floors now stands free, sculpturally centred in a room and asking questions around whether it was relocated or if the fabric around it was meticulously removed.

figs.x-xii

In the unravelling, aesthetic choices from the mid-19th century rub up against more historic features. Where we normally see the skin of architecture, from a single organised moment, here strata and histories are revealed and reordered. A compression of indeterminable times creates a version of the place that somehow straddles its entire life, from the 15th to 21st centuries.

This is an approach that Astakhishvili has used before, though more often in a white-walled gallery space, turning artworld perfection into a construction site space of betweenness. Here, with the artist working onto and into a building lost to ruin and ahead of it becoming a (re)construction site, the artist had opportunity to more deeply play with the methodology. Then, into it all are 47 artworks, some presented with absolute clarity – on plinths or in frames – and others disappearing into the atmosphere and shadows of the place.

figs.xiii-xv

Artworks by Astakhishvili carry other architectural memories. Beautiful neighbour (2024) contains a 3d-printed architectural model in collage with drawing on a slapdash plaster backing. taste (snoring and the sound of pigeons) (2025) sits as a monolith in the ground floor, cutlery and found objects embedded into what reads as a concrete mass filling a room. I love seeing myself through the eyes of others (2025) is a vast lightbox of plastic covered in paint and photos, a light inside where visitors can’t go, an unreachable room within a room.

figs.xvi-xviii

Works by others are positioned within the building as if to suggest they had always been there, perhaps uncovered by artistic excavation. A work made with Dylan Peirce appropriates a dismantled ventilation unit and drywall plaster. Thea Djorjadze’s sculptural work is formed of eight twisted and torn pieces of aluminium which could easily be read as construction site castoffs. Astakhishvili and James Richards collaborated to create Our Friends In the Audience (2024), a marouflage on canvas print, a portrait of a young girl solemnly staring back – a hauntological reach, perhaps, to the girls of the school that once owned this building.

One work, Suddenly the world became loud II, made last year with Zurab Astakhishvili, the artist’s father, reads like a cardboard tower block encased in Perspex, as if a preservation, protection, or prison. Shortly after the opening of to love and devour, Zurab passed away, ending a familial artistic dialogue. The work now takes on other meanings, standing as a self-crafted memorial, just as the building surrounding it also contains palimpsests of lives lived, loves lost, stories made and remade, some visible, some secreted.

fig.xix

Many works may not be noticed. Photos left on ledges, scribbles into the architectural marginalia, and print covering windows. The project relies on natural light, further creating the mood and sense of timelessness. Altogether, it’s a gesamtkunstwerk in which architecture and artwork combine into some new space between. And in a city punctuated by annual art and architecture Biennials, resplendent in the grand, gaudy, and sublime, it’s a welcome disruption and exciting start to what the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation and building may evolve to become.

Tolia Astakhishvili (b. 1971) works and lives between Berlin and Tbilisi. Her art practice includes sculpture, drawing, painting, sound, video and writing. Her architectural environments, which integrate these various media, are designed in conversation with the exhibition site. They evoke spaces in transformation, like a suspended construction site whose origins and completion remain undefined. Everyday objects, drawings, photographs, mural inscriptions and videos suggest a diffuse human presence. Together, they weave a fictional narrative marked by a psychological dimension, sometimes tinged with surrealism. Her recent solo exhibitions include Result, LC Queisser, Tbilisi; between father and mother, Sculpture Center, New York (2024); The First Finger (chapter II), Haus am Waldsee, Berlin (2023); The First Finger, Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn (2023); I Think It's Closed, Bielefelder Kunstverein, Bielefeld (2023); I am the secret meat, Felix Gaudlitz, Vienna (2022). She has also participated in group exhibitions at the MACRO Museum, Rome; Condo Complex, London (2024); Kunsthalle Zürich, Zürich; Emalin, London; Molitor Gallery, Berlin; LC Queisser, Tbilisi (2023); Shahin Zarinbal, Berlin; LC Queisser, Tbilisi (2022); Art Hub Copenhagen, Copenhagen; Räume für Kunst, Kerpen; Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn; Capitain Petzel Gallery, Berlin (2021); Malmö Konsthall, Malmö (2019); Cabinet, London (2018). In 2025, her work will be exhibited at the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation in Venice, under the direction of Hans Ulrich Obrist, and as part of The Gatherers at MoMA PS1, in New York.

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist & educator interested in cities, architecture & culture. He has written for Wallpaper*, Canvas, The Architect’s Newspaper, RIBA Journal, Icon, Art Monthly & more. He teaches history & theory at UCL Bartlett & is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.willjennings.info