Goldsmiths degree show: the highlights

We visit the degree shows at Goldsmiths College, University of London, to take a closer look at nine artists whose fine art practice intersects with architecture & landscape architecture. Featuring the work of Tom Bull, Pascal Marcel Dreier, Ali Glover, Jean-François Krebs, Chris MacInnes, Barney Pau, Jacob George Wilson, Scott Young, & Anna Wachsmuth.

Degree shows are hard. They are hard for the finishing

students, who must encapsulate years of knowledge and exploratory research into

a single installation for public and adjudicator consumption. But, they can

also be hard for a visitor who must navigate countless numbers of creatives and

disparate ideas all vying for attention, consideration, and critical impact.

But works can jump out, especially when navigating the wealth of works with a particular vantage. And so recessed.space visited the graduate exhibition of Goldsmiths College 2022 Degree Shows to select which works interrogate that particular space between fine arts and architectures, and through them which issues are bubbling to the surface…

Jean-François Krebs

Photophilia

www.jeanfrancoiskrebs.com

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.i-ix

For a generation born deep within the Anthropocene, and who will be tasked with developing, communicating, and enacting the solutions to its ever-increasing impacts, it’s unsurprising that ecology recurs frequently amongst the works and research of Goldsmiths’ graduates. It doesn’t all, however, interact with architecture in the way Krebs’ plays and corrupts the safe space of the building’s form.

It's not only opening up the floor void, but utilising its very infrastructure and form – the darkness displays the fluorescence of uranium glass, while the cables and pipes offer a substructure to build the installation around. It hugs the architecture, erupting through it. At a time when celebrity architects seem distracted by packing reinforced concrete balconies with hanging plants to impress an ideas of ecological soundness, Krebs suggests a world in which that same ecology can grow from within, using the very physicality of a building to flourish.

The work has been shown before, each time responding to site conditions and its own evolution. This is its third iteration, sinking beneath the supported floor and into the darkness beneath. Krebs hopes that its next incarnation will be permanent, as an architectural structure – perhaps a greenhouse – with plants chosen for their transformative properties. Having previously studied horticulture and landscape architecture at various European institutions, the artist now seems ready to root that research and knowledge into a physical space.

Barney Pau

Arcadia

www.barneypau.com

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.x-xiv

A domestic scene. Lace curtains gently dance in a light breeze coming through an open window which frames a view upon romantic industrial fields – neatly mowed lawn, combine, clouds, crops, and a lorry transporting freshly baked bread. Look close, it’s not as it seems, the domesticity here is queer – a flaccid breadstick flops over the window frame, and upon inspection the decorative pattern of the wallpaper isn’t a floral theme but rural buggery. This is the imagined house of a radical queer baker, and Pau is interested in important conflation of ecology and nature in queer and homosexual thinking.

The baker kneads his bread, and it needs him, it is a compassionate relationship. Pau writes about the notion of monocultures, an agricultural term relating to use of a singular crop in a given area, and while this kind of singularity and narrowing may be culturally perceived as a strength, a unity, in actual fact it is through mixing, diversity, with queer and minority ingredients that a recipe not only becomes more interesting and flavoursome but also stronger – as in the case of this baker’s 12 hour fermented sourdough loaf, baked from a deep mix of grains, legumes and seeds.

The framing, we inside the mise en scene and the neat, picket-fenced world outside, creates acknowledgement of the personal and public, the way our internal lives may be hidden from those outside, and yet the product of them – in the bakers’ case his bread – is still valuable nourishment, despite its genesis remaining unknown to those who benefit from its strength.

Ali Glover

When the seeping starts & vibrations, slipping, walking

www.aliglover.com

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.xv-xix

It’s a sudden shock to turn the corner in the Will Alsop designed high-ceiling factory to contemporary art that is the Ben Pimlott tower at Goldsmiths and find yourself under an office-like suspended ceiling and standing upon tired, dry carpet tiles. It’s an uncanny shift, and there’s a feeling of Mike Nelson meets Jacques Tati’s Playtime, the way mundane interior becomes this site of artistic concern.

It's MFA Fine Art graduate Ali Glover’s installation. An artist interested in site interventions to think about architectural infrastructure, the use of pre-fabricated objects makes one think of how decoration not only changes situation, but also how it covers up. Step back from the installation and you can see that the space above the dropped ceiling seems larger than that below, and compression and concealment become architectural devices.

Two carpet tiles and a ceiling panel are worn. Has everything else been maintained while these left to rot, or have these suffered more than the rest? There are speakers in the ceiling. Glover’s work utilises field recordings to document space, then imposing them into these new situated spaces. Where artists in such situations as a degree show feel as if they must fill the space, to draw the eye to visual spectacle, it takes a bravery to create a hollow, which a visitor may pass through without any realisation other than subconscious unease, but which provokes a more curious anxiety if they were to dwell.

Pascal Marcel Dreier

Imorthufora

www.pascaldreier.com

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.xx-xxvi

In 2006 a juvenile female bottlenose whale swam up the Thames estuary and into central London. Five metres long, she became a spectacle followed not only by TV cameras but also crowds lining the bank. Her slow, traumatic death only became more public when hoisted out of the river and carried back to the Thames’ mouth by barge, slowly crushing under her own weight, eventually dying onboard convulsing, panicking, and with muscle problems. She was in distress and lost, collisions with boats and the riverbed contributing to her death, and while humans were trying to help the situation the public exhibitionism and live-streaming of such trauma was unnerving and odd.

The foreshore of the Thames is an ossuary. Bones of boars, deer, and other past dinners have been disposed of into the water and now form the beach as waters drift out. Showing the marks of Medieval to Victorian knife marks where meat has been scraped away, Dreier has mudlarked some of those bones, forming an imagined Monstrum from the variously scavenged animal components. It is laid out on the floor, a Frankenstein imaginary formed of all London’s histories, of all the individual stories of animalistic loss compounded into the darkness of the waters.

Alongside the installation, the artist is conducting public mudlarking events under the umbrella of IMORTHUFORA, the name and acronym of his institution. These are publicly participatory events, and through the extraction of stories of human violence against the city’s animal citizens over previous centuries, there is perhaps an undoing or redress to the kind of public

London may be a metropolis manmade over centuries with concrete, tarmac, pollution, and brick, but underneath all that modernity and progression is an historic nature. Overwhelmingly, however, it is dead – crushed under all we have created.Dreier is interested in those lost lives, and how they compound into the city’s history, guilt, and possible future.

Tom Bull

www.tombull.co.uk

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.xxvii-xxxiii

There’s a horror film feel here. A stool in front of a wood burner seemed to have been subjected to something traumatic as if melted by napalm or intense heat. A nearby horse trough has the same black tarnish, but inside there’s water. No horse drinking, nobody on the stool, there’s an eeriness and absence which is also noticeable on the noticeboards, frames tarnished and burnt, there are no pinned notices.

His work extends outside, onto the paved terrace which sits under Will Alsop’s birds nest like sculptural appendage to the building. Here, hay bales tightly wrapped in black plastic sit, adrift from their rural logic and as punctuation to an unknowable sentence. A small house sits slightly sunken in the paving. Reminiscent of a child’s Wendy house it is formed of clay and soil, a metal chimney puncturing its pitched roof delivering smoke to the city sky from a burner which takes up half of the internal floorplan.

Inside again, a single rabbit hutch with a thatched roof seems to have survived the devastation, but its inside has childhood photos pinned up, and an unsettling image of a kitchen scene with breezeblocked up window. These photos, and the cosy hutch and architectural thatch above, are symbols of nostalgia, but both nostalgia and the rural are often scared of external realities puncturing their myth. Perhaps the breezeblocked window is to keep out the fire and napalm that seems to have taken over everything else in this set piece, to lock inside and protect a romantic idea from external forces.

Christopher MacInnes

Impotent Island

www.christophermacinnes.com

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.xxxiv-xxxvii

“All I see up inside, the sort of innards of the warehouse, there’s a sort of gantry, then above the gantry … somebody had sort of painted this grinning face in spray paint, it was dead high up, really high up, it must’ve been dangerous to get up there.”

It’s the face itself telling me this, the graffiti animated into a stuck talking head speaking of its own existence. The northern English male voice speaks of a personal experience of industrial sheds, detritus from another age littering a Sheffield which wishes to project a more modern, polished existence. But the sheds remain, and the history of the place echoes within their empty shells.

The voice speaks of those innards: “It was quite hard for me to imagine that these sort of foundries and warehouses and things had some kind of like interior.” Industrial architecture like this has two existences, one as part of the urban silhouette, structural fabric of the city, and then the insides which are apart from the city, spaces of memory, haunting, absence, and once energy. Here, the architecture is a narrow shell, a robust exterior projecting a different reality to the thoughtful reverberation inside.

But such architecture is also cliché, especially when considered down south in a contemporary art setting. The shape it projects, how its read, speaks of industrial grit, logical and rational brute power, a mechanical force which transforms materials into cold solid steel. To mould and compress steel requires immense pressure, these suspended models richly glowing from within exuding a sublime power despite the void.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.xxxviii-xlii

The elements are seemingly scattered around the space, but there’s a deliberateness in the way they are distributed. Glazed ceramic circular – or parts of a circle – are placed around, one slipping off a concrete slab. But, as eyes dart around the arrangement they are constantly pulled back to a video on the back wall. Flames are lapping into the dark night, the only movement in this fragmented still life.

The roof that’s on fire in the video is of a hotel in eastern Germany. It was due to have been reopened as emergency refugee accommodation until the fire broke out. The artist is interested in the symbolism of this at a time of a resurgence in the far right in Germany and across Europe. The wider arrangement uses materials to think about German transgenerational trauma, a subject perhaps notably broached culturally by the generation of the likes of Paul Celan, WG Sebald, and Anselm Kiefer, but with a new generation looking both backwards and forwards the thoughts are becoming considered within a conceptual art frame.

The pebbled concrete slabs speak to the materials of post-war public space, a ceramic glazed vase standing in for the domestic. And it’s the relationship between these materials and spaces in which trauma is preserved, aired, and understood. Pebbledash sections are framed and project from the wall as if advertisements. But the cold concrete doesn’t project anything, it only sucks in the atmosphere and keeps meaning as tightly bound as the trapped pebbles

Jacob George Wilson

Low Low's Air-Raid, before and after congress

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.xliii-xlix

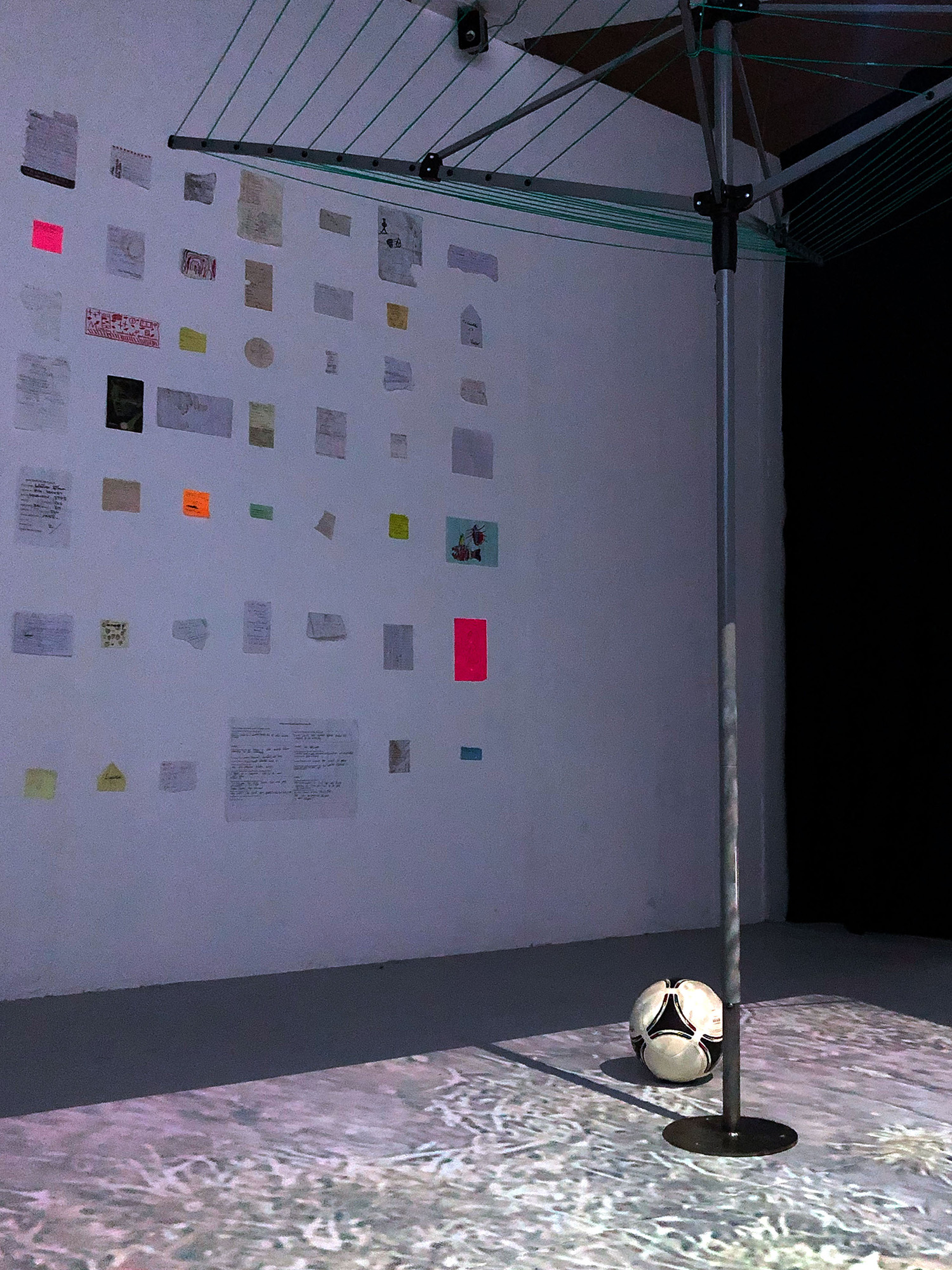

Having studied MA Artist Film & Moving Image, Wilson’s work is more sculptural and immersive than a traditional durational film projection. Central in his space is an empty four-sided rotary garden clothes dryer, a football sat near its base. A patch of this imaginary domestic garden’s grass is projected down, as if an inverse shadow of the rail itself. Over time, the setting changes through different nature and into a more urban setting. A parallelogram projection against the corner of the room is another video work, aeroplanes recurring an passing shot. In the corner, a CRT monitor on the floor with a slideshow of South London mundane urbanity, a series of answering machine messages playing over the top, rambling, confused, angry or nervous voice notes.

All together they create as much a mood as an installation, it’s not one of joy or excitement, just the everyday and ordinary, simple urban fragments of place and those who get through each day within it. More fragments form a grid on the wall, notes found on the ground by the artist which are now presented with an authorial presence the originator would never have expected. A note to Gemma from Susan with a reference to a Bible verse in Romans. A shopping list. A pink Post It with the ominous words endtimes video. Directions for the 63 bus from Stop D to Kings Cross. Christopher Green’s hospital number. Ripped extracts of a children’s musical score.

These, the answering machine messages, and all the other details of the everyday speak to a celebration of that which is not even really considered, but is a lived experience. But here, they are recomposed into a poetry, elevating the ordinary through rhythm.

Scott Young

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

An ornate marble panel runs along the length of the space, light flooding in through the rooflight above only seeming to pick out its veins more. We are in the Laurie Grove Baths, a former swimming pool now used by Goldsmiths as studio and degree show exhibition space, and the light flooding down seems to meet the clouds in the artist’s paintings. The wipe-clean marble surfaces seem to be at home here, the luxurious material of domestic bathrooms and private spas, there’s an allure and richness.

On closer inspection, the marble is not what it seems. It is not quarried but a flat print, the compounded geology hinted at in its marbling but an illusion. Similarly, the marble plinth in the centre of the space is not solid stone, and the trompe l'oeils paintings suggest a depth in both space and meaning that we now question.

Marble is a sensual material, asking to be caressed. But it’s not just a sybaritic space, it also hints at the erotic, carnal, fetishistic. Painted and physical ironmongery punctuates the installation and the paintings, one work features a leather harness, another a close up of sensual lipsticked lips on a head rocking back and out of the frame. The faux wood and marble plinths have their luxurious surface penetrated with hardware, like a pierced body. Another painting eschews anything bodily, but reads like a shop counter of office sideboard, displaying phantasmagoric sculptures and exotic flowers. These are all spaces of consumption - whether bodily, architecturally, or commercially - but who is consumed, who is consuming?

But works can jump out, especially when navigating the wealth of works with a particular vantage. And so recessed.space visited the graduate exhibition of Goldsmiths College 2022 Degree Shows to select which works interrogate that particular space between fine arts and architectures, and through them which issues are bubbling to the surface…

Jean-François Krebs

Photophilia

www.jeanfrancoiskrebs.com

figs.i-ix

For a generation born deep within the Anthropocene, and who will be tasked with developing, communicating, and enacting the solutions to its ever-increasing impacts, it’s unsurprising that ecology recurs frequently amongst the works and research of Goldsmiths’ graduates. It doesn’t all, however, interact with architecture in the way Krebs’ plays and corrupts the safe space of the building’s form.

It's not only opening up the floor void, but utilising its very infrastructure and form – the darkness displays the fluorescence of uranium glass, while the cables and pipes offer a substructure to build the installation around. It hugs the architecture, erupting through it. At a time when celebrity architects seem distracted by packing reinforced concrete balconies with hanging plants to impress an ideas of ecological soundness, Krebs suggests a world in which that same ecology can grow from within, using the very physicality of a building to flourish.

The work has been shown before, each time responding to site conditions and its own evolution. This is its third iteration, sinking beneath the supported floor and into the darkness beneath. Krebs hopes that its next incarnation will be permanent, as an architectural structure – perhaps a greenhouse – with plants chosen for their transformative properties. Having previously studied horticulture and landscape architecture at various European institutions, the artist now seems ready to root that research and knowledge into a physical space.

Barney Pau

Arcadia

www.barneypau.com

figs.x-xiv

A domestic scene. Lace curtains gently dance in a light breeze coming through an open window which frames a view upon romantic industrial fields – neatly mowed lawn, combine, clouds, crops, and a lorry transporting freshly baked bread. Look close, it’s not as it seems, the domesticity here is queer – a flaccid breadstick flops over the window frame, and upon inspection the decorative pattern of the wallpaper isn’t a floral theme but rural buggery. This is the imagined house of a radical queer baker, and Pau is interested in important conflation of ecology and nature in queer and homosexual thinking.

The baker kneads his bread, and it needs him, it is a compassionate relationship. Pau writes about the notion of monocultures, an agricultural term relating to use of a singular crop in a given area, and while this kind of singularity and narrowing may be culturally perceived as a strength, a unity, in actual fact it is through mixing, diversity, with queer and minority ingredients that a recipe not only becomes more interesting and flavoursome but also stronger – as in the case of this baker’s 12 hour fermented sourdough loaf, baked from a deep mix of grains, legumes and seeds.

The framing, we inside the mise en scene and the neat, picket-fenced world outside, creates acknowledgement of the personal and public, the way our internal lives may be hidden from those outside, and yet the product of them – in the bakers’ case his bread – is still valuable nourishment, despite its genesis remaining unknown to those who benefit from its strength.

Ali Glover

When the seeping starts & vibrations, slipping, walking

www.aliglover.com

figs.xv-xix

It’s a sudden shock to turn the corner in the Will Alsop designed high-ceiling factory to contemporary art that is the Ben Pimlott tower at Goldsmiths and find yourself under an office-like suspended ceiling and standing upon tired, dry carpet tiles. It’s an uncanny shift, and there’s a feeling of Mike Nelson meets Jacques Tati’s Playtime, the way mundane interior becomes this site of artistic concern.

It's MFA Fine Art graduate Ali Glover’s installation. An artist interested in site interventions to think about architectural infrastructure, the use of pre-fabricated objects makes one think of how decoration not only changes situation, but also how it covers up. Step back from the installation and you can see that the space above the dropped ceiling seems larger than that below, and compression and concealment become architectural devices.

Two carpet tiles and a ceiling panel are worn. Has everything else been maintained while these left to rot, or have these suffered more than the rest? There are speakers in the ceiling. Glover’s work utilises field recordings to document space, then imposing them into these new situated spaces. Where artists in such situations as a degree show feel as if they must fill the space, to draw the eye to visual spectacle, it takes a bravery to create a hollow, which a visitor may pass through without any realisation other than subconscious unease, but which provokes a more curious anxiety if they were to dwell.

Pascal Marcel Dreier

Imorthufora

www.pascaldreier.com

figs.xx-xxvi

In 2006 a juvenile female bottlenose whale swam up the Thames estuary and into central London. Five metres long, she became a spectacle followed not only by TV cameras but also crowds lining the bank. Her slow, traumatic death only became more public when hoisted out of the river and carried back to the Thames’ mouth by barge, slowly crushing under her own weight, eventually dying onboard convulsing, panicking, and with muscle problems. She was in distress and lost, collisions with boats and the riverbed contributing to her death, and while humans were trying to help the situation the public exhibitionism and live-streaming of such trauma was unnerving and odd.

The foreshore of the Thames is an ossuary. Bones of boars, deer, and other past dinners have been disposed of into the water and now form the beach as waters drift out. Showing the marks of Medieval to Victorian knife marks where meat has been scraped away, Dreier has mudlarked some of those bones, forming an imagined Monstrum from the variously scavenged animal components. It is laid out on the floor, a Frankenstein imaginary formed of all London’s histories, of all the individual stories of animalistic loss compounded into the darkness of the waters.

Alongside the installation, the artist is conducting public mudlarking events under the umbrella of IMORTHUFORA, the name and acronym of his institution. These are publicly participatory events, and through the extraction of stories of human violence against the city’s animal citizens over previous centuries, there is perhaps an undoing or redress to the kind of public

London may be a metropolis manmade over centuries with concrete, tarmac, pollution, and brick, but underneath all that modernity and progression is an historic nature. Overwhelmingly, however, it is dead – crushed under all we have created.Dreier is interested in those lost lives, and how they compound into the city’s history, guilt, and possible future.

Tom Bull

www.tombull.co.uk

figs.xxvii-xxxiii

There’s a horror film feel here. A stool in front of a wood burner seemed to have been subjected to something traumatic as if melted by napalm or intense heat. A nearby horse trough has the same black tarnish, but inside there’s water. No horse drinking, nobody on the stool, there’s an eeriness and absence which is also noticeable on the noticeboards, frames tarnished and burnt, there are no pinned notices.

His work extends outside, onto the paved terrace which sits under Will Alsop’s birds nest like sculptural appendage to the building. Here, hay bales tightly wrapped in black plastic sit, adrift from their rural logic and as punctuation to an unknowable sentence. A small house sits slightly sunken in the paving. Reminiscent of a child’s Wendy house it is formed of clay and soil, a metal chimney puncturing its pitched roof delivering smoke to the city sky from a burner which takes up half of the internal floorplan.

Inside again, a single rabbit hutch with a thatched roof seems to have survived the devastation, but its inside has childhood photos pinned up, and an unsettling image of a kitchen scene with breezeblocked up window. These photos, and the cosy hutch and architectural thatch above, are symbols of nostalgia, but both nostalgia and the rural are often scared of external realities puncturing their myth. Perhaps the breezeblocked window is to keep out the fire and napalm that seems to have taken over everything else in this set piece, to lock inside and protect a romantic idea from external forces.

Christopher MacInnes

Impotent Island

www.christophermacinnes.com

figs.xxxiv-xxxvii

“All I see up inside, the sort of innards of the warehouse, there’s a sort of gantry, then above the gantry … somebody had sort of painted this grinning face in spray paint, it was dead high up, really high up, it must’ve been dangerous to get up there.”

It’s the face itself telling me this, the graffiti animated into a stuck talking head speaking of its own existence. The northern English male voice speaks of a personal experience of industrial sheds, detritus from another age littering a Sheffield which wishes to project a more modern, polished existence. But the sheds remain, and the history of the place echoes within their empty shells.

The voice speaks of those innards: “It was quite hard for me to imagine that these sort of foundries and warehouses and things had some kind of like interior.” Industrial architecture like this has two existences, one as part of the urban silhouette, structural fabric of the city, and then the insides which are apart from the city, spaces of memory, haunting, absence, and once energy. Here, the architecture is a narrow shell, a robust exterior projecting a different reality to the thoughtful reverberation inside.

But such architecture is also cliché, especially when considered down south in a contemporary art setting. The shape it projects, how its read, speaks of industrial grit, logical and rational brute power, a mechanical force which transforms materials into cold solid steel. To mould and compress steel requires immense pressure, these suspended models richly glowing from within exuding a sublime power despite the void.

figs.xxxviii-xlii

The elements are seemingly scattered around the space, but there’s a deliberateness in the way they are distributed. Glazed ceramic circular – or parts of a circle – are placed around, one slipping off a concrete slab. But, as eyes dart around the arrangement they are constantly pulled back to a video on the back wall. Flames are lapping into the dark night, the only movement in this fragmented still life.

The roof that’s on fire in the video is of a hotel in eastern Germany. It was due to have been reopened as emergency refugee accommodation until the fire broke out. The artist is interested in the symbolism of this at a time of a resurgence in the far right in Germany and across Europe. The wider arrangement uses materials to think about German transgenerational trauma, a subject perhaps notably broached culturally by the generation of the likes of Paul Celan, WG Sebald, and Anselm Kiefer, but with a new generation looking both backwards and forwards the thoughts are becoming considered within a conceptual art frame.

The pebbled concrete slabs speak to the materials of post-war public space, a ceramic glazed vase standing in for the domestic. And it’s the relationship between these materials and spaces in which trauma is preserved, aired, and understood. Pebbledash sections are framed and project from the wall as if advertisements. But the cold concrete doesn’t project anything, it only sucks in the atmosphere and keeps meaning as tightly bound as the trapped pebbles

Jacob George Wilson

Low Low's Air-Raid, before and after congress

figs.xliii-xlix

Having studied MA Artist Film & Moving Image, Wilson’s work is more sculptural and immersive than a traditional durational film projection. Central in his space is an empty four-sided rotary garden clothes dryer, a football sat near its base. A patch of this imaginary domestic garden’s grass is projected down, as if an inverse shadow of the rail itself. Over time, the setting changes through different nature and into a more urban setting. A parallelogram projection against the corner of the room is another video work, aeroplanes recurring an passing shot. In the corner, a CRT monitor on the floor with a slideshow of South London mundane urbanity, a series of answering machine messages playing over the top, rambling, confused, angry or nervous voice notes.

All together they create as much a mood as an installation, it’s not one of joy or excitement, just the everyday and ordinary, simple urban fragments of place and those who get through each day within it. More fragments form a grid on the wall, notes found on the ground by the artist which are now presented with an authorial presence the originator would never have expected. A note to Gemma from Susan with a reference to a Bible verse in Romans. A shopping list. A pink Post It with the ominous words endtimes video. Directions for the 63 bus from Stop D to Kings Cross. Christopher Green’s hospital number. Ripped extracts of a children’s musical score.

These, the answering machine messages, and all the other details of the everyday speak to a celebration of that which is not even really considered, but is a lived experience. But here, they are recomposed into a poetry, elevating the ordinary through rhythm.

Scott Young

An ornate marble panel runs along the length of the space, light flooding in through the rooflight above only seeming to pick out its veins more. We are in the Laurie Grove Baths, a former swimming pool now used by Goldsmiths as studio and degree show exhibition space, and the light flooding down seems to meet the clouds in the artist’s paintings. The wipe-clean marble surfaces seem to be at home here, the luxurious material of domestic bathrooms and private spas, there’s an allure and richness.

On closer inspection, the marble is not what it seems. It is not quarried but a flat print, the compounded geology hinted at in its marbling but an illusion. Similarly, the marble plinth in the centre of the space is not solid stone, and the trompe l'oeils paintings suggest a depth in both space and meaning that we now question.

Marble is a sensual material, asking to be caressed. But it’s not just a sybaritic space, it also hints at the erotic, carnal, fetishistic. Painted and physical ironmongery punctuates the installation and the paintings, one work features a leather harness, another a close up of sensual lipsticked lips on a head rocking back and out of the frame. The faux wood and marble plinths have their luxurious surface penetrated with hardware, like a pierced body. Another painting eschews anything bodily, but reads like a shop counter of office sideboard, displaying phantasmagoric sculptures and exotic flowers. These are all spaces of consumption - whether bodily, architecturally, or commercially - but who is consumed, who is consuming?