Echoing the architecture: Trevor Mathison’s sculpted sound

As a composer, sound designer, recordist & artist, Trevor Mathison has long been rooted in British art & film history & was a founding membed of The Black Audio Film Collective. Goldsmiths CCA are exhibiting his work in the exhibition From Signal to Decay: Volume 1, an installation in deep conversation within the building it sits. Robert Barry went along to listen in.

Standing in

the centre of the Oak Foundation Gallery, in the basement of Goldsmiths Centre

for Contemporary Art, and looking north, you can see layers. Rising before you,

multiple strata of material history in brusque alignment. Straight ahead, in

the corner of the room, there’s a rectangle of brushed concrete, all uneven

greys competing for space on the hastily smoothed surface. Behind that, and

stretching about three metres up, a wall of sandy-coloured London stock brickwork,

variegated and pockmarked by time, once the interior divider of Laurie Grove

Baths’ Victorian boiler room. Beyond that, rising another three metres or so,

the mottled white tiles of the bathhouse’s old public laundry room. Finally,

rising even further above that, you can see what must once have been one of the

building’s exterior walls, in a mix of classic red bricks and more London

stock, blackened by the smog of ages to a deep burnished brown.

![]()

![]()

This quasi-archaeological appearance of the space itself is the consequence of Assemble’s radical reconfiguring of the building before its opening in 2018, a means, as the group’s Paloma Strelitz told the Architect’s Journal back then, of creating “a sense of openness and porosity” throughout.[i] But close your eyes for a moment and listen, and at the moment at least, you can hear something similar at play. Trevor Mathison’s soundworks are just as brindled and scarred, more textural than melodic or harmonious. They interact and overlap from speakers dispersed across the basement galleries in constantly shifting alignment, with different layers of sound competing for your attention at any moment, each one a seemingly solid edifice but marked and transformed by the passing of time, wearing history like a patina of dust. Talking to Mathison upstairs, in the offices above the gallery, he describes a process of “listening through” the various elements of the show.

![]()

![]()

![]()

There are several different elements to be listened through, and that make up the overall soundscape of the show. In the Oak Foundation Gallery, four speakers play selections from Mathison’s archive of compositions, going back through three and a half decades of work as a film composer and sound designer for the like of John Akomfrah and Isaac Julien, as well as installation and live performance work with Gary Stewart as Dubmorphology. Each individual track has been newly remixed and recomposed together to make one long seamless composition. In the next room, a second quadrophonic speaker setup plays sounds recorded by Mathison in the CCA itself, seeking out the “sweet spots in the building” where the historical properties of the space seem to seep into its acoustic signature.

A further set of speakers in an adjoining corridor broadcasts noises directly from the street outside (during my visit, I could hear the squeal of traffic, distant voices). Finally, in the back room of the space, a wide rectangular screen plays Mathison’s film, Untitled (2018), with its own soundtrack built of field recordings and synthesizer glitches. Each of these “moving parts,” as he puts it, then “interlock” into a signal composition, with the different elements “making space for the other pieces” at different times, creating a sonic arena that the viewer can move through, making one’s own body into a kind of mixing desk.

![]()

![]()

![]()

In the early 80s, Mathison, alongside Akomfrah, Edward George, Reece Auguiste, Lina Gopaul, and others, was a founder member of the Black Audio Film Collective, part of a brace of new collectives formed by Black British artists supported by the Greater London Council and the new Channel 4 (including the Ceddo Film and Video Workshop and the Sankofa Film and Video Collective formed by Julien with Martina Attille, Maureen Blackwood, and Nadine Marsh-Edwards). For Akomfrah’s ground-breaking Handsworth Songs (1986), Mathison acted as set designer, camera operator, sound recordist and composer, building a rich sonic stew from archive recordings of calypso tunes, reggae, brass bands, and street noise, all montaged together and cloaked in space echo in the manner of an hour-long dub mix.

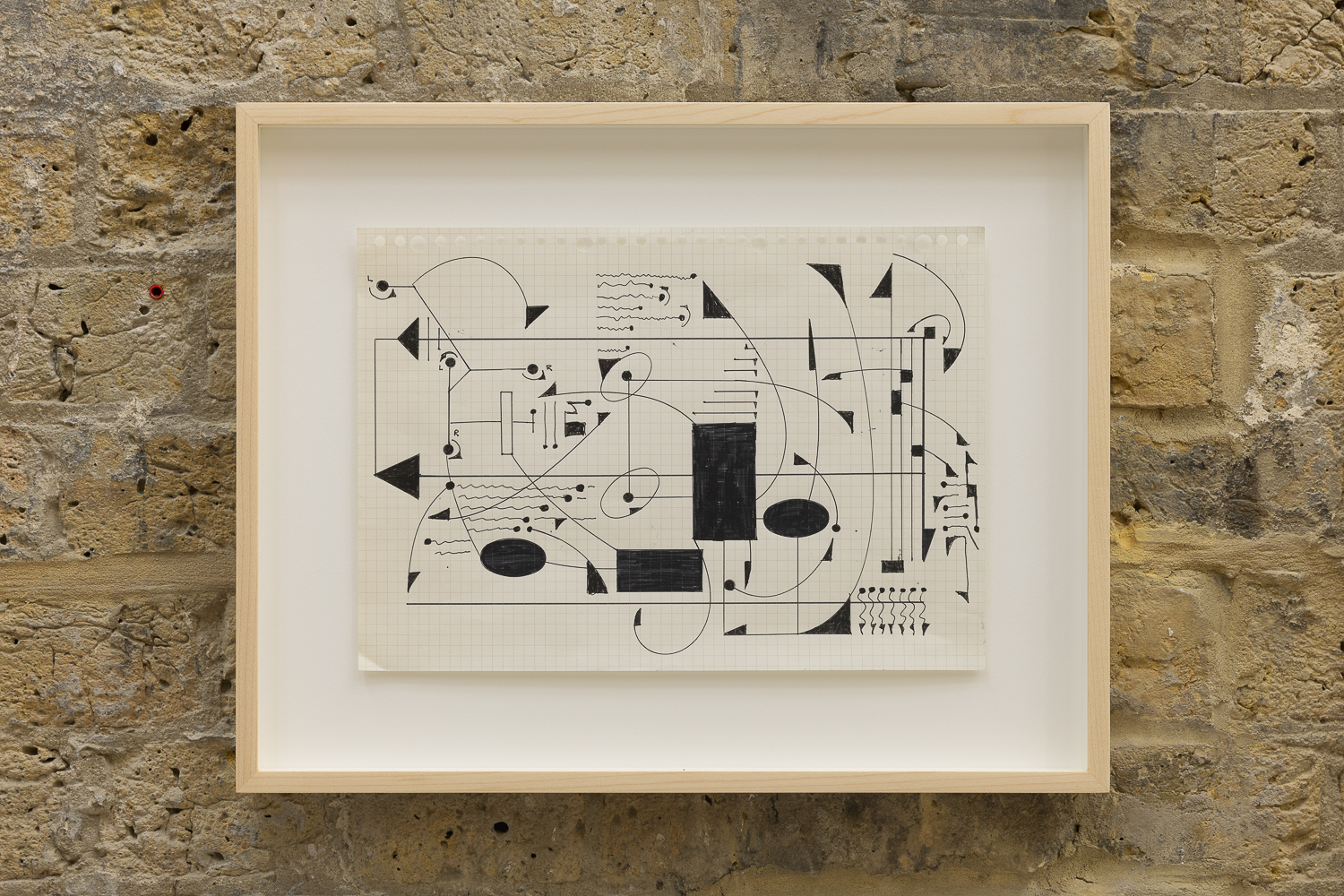

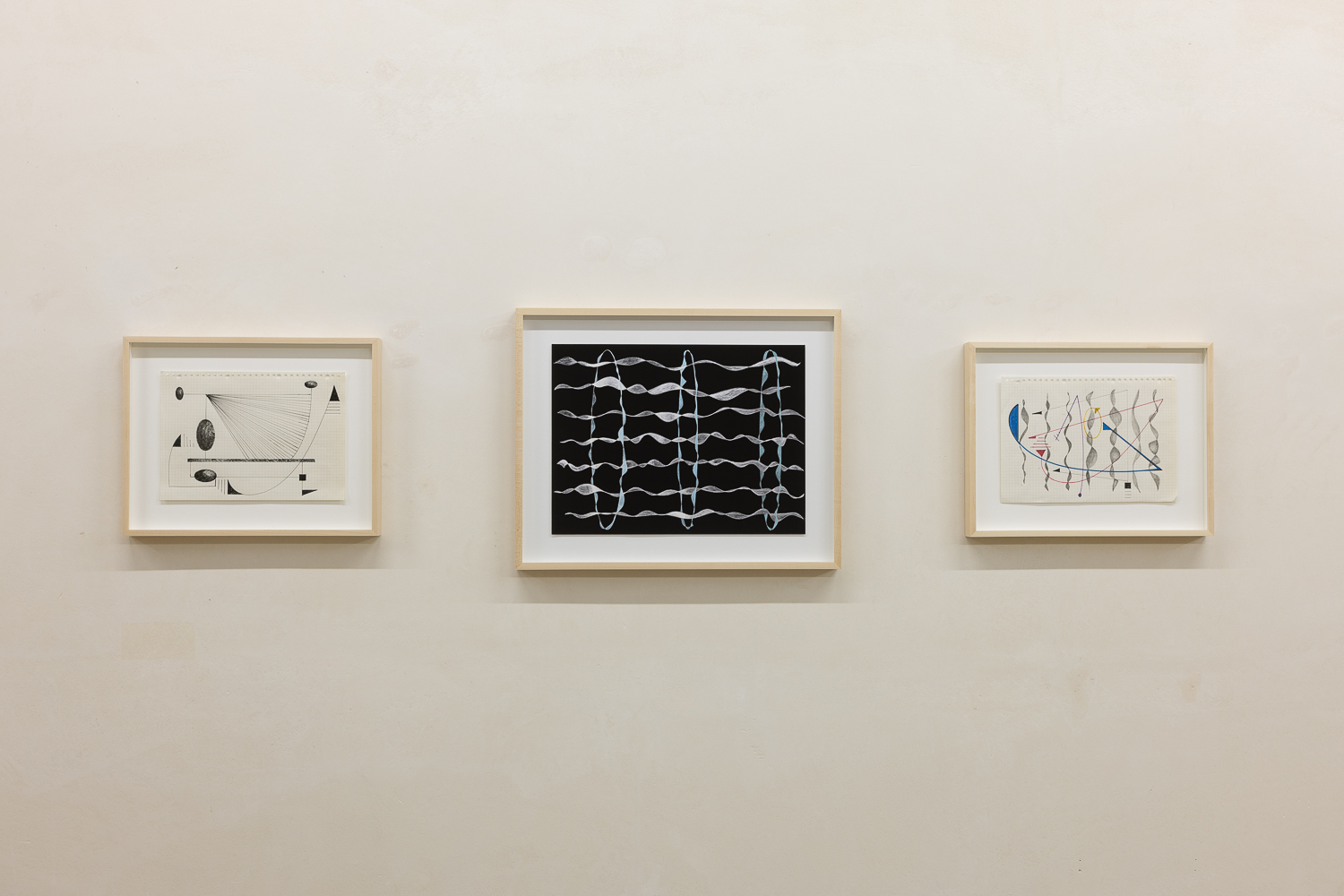

Mathison identifies dub, as a means of processing sound and a form of sonic investigation, as the thread running throughout his work, right up to the present day. Back in the 80s, he would use answerphone tapes to make loops, snatching fragments of sound off the radio or TV before re-recording the sounds onto a second tape deck, manipulating the sound by hand, or using electronic effects in the process. Many of those old tapes, with sleeves vividly illustrated by Mathison using cuttings from newspapers and magazines, frequently overpainted and deliriously collaged, are presented here in one of several vitrines taking up the central area of the gallery. Alongside these tape boxes, there are old sketchbooks, photographs, and graphic scores that look somewhere between Cornelius Cardew’s Treatise, record sleeves by Sun Ra, and the circuit diagram of some impossible machine.

![]()

![]()

![]()

It seems almost extraordinary that after forty years of work, this is Mathison’s first solo exhibition in a UK institution. There’s a great wealth of material here, much of it rich and heady, testament to a restless creative imagination. Across the three rooms and various small peripheral spaces of the CCA, Mathison here makes sound into something tangible, tactile, and highly plastic. The artist who originally trained as a sculptor speaks now of “sculpting sound” and for once the metaphor feels apt. There is a solidity and materiality to it. You can feel this music – in every sense of the word. That dissonant, textural gnarliness never distracts from the strong emotional tugs that rise from the depths of these sonics like so many half-buried memories. The CCA has been reconfigured as the site of an investigation. The methodology, as ever, is dub.

[1]

Read Rob Wilson’s review of Goldsmiths CCA for Architects’

Journal at: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/buildings/assemble-raises-the-roof-on-goldsmiths-centre-for-contemporary-art

This quasi-archaeological appearance of the space itself is the consequence of Assemble’s radical reconfiguring of the building before its opening in 2018, a means, as the group’s Paloma Strelitz told the Architect’s Journal back then, of creating “a sense of openness and porosity” throughout.[i] But close your eyes for a moment and listen, and at the moment at least, you can hear something similar at play. Trevor Mathison’s soundworks are just as brindled and scarred, more textural than melodic or harmonious. They interact and overlap from speakers dispersed across the basement galleries in constantly shifting alignment, with different layers of sound competing for your attention at any moment, each one a seemingly solid edifice but marked and transformed by the passing of time, wearing history like a patina of dust. Talking to Mathison upstairs, in the offices above the gallery, he describes a process of “listening through” the various elements of the show.

There are several different elements to be listened through, and that make up the overall soundscape of the show. In the Oak Foundation Gallery, four speakers play selections from Mathison’s archive of compositions, going back through three and a half decades of work as a film composer and sound designer for the like of John Akomfrah and Isaac Julien, as well as installation and live performance work with Gary Stewart as Dubmorphology. Each individual track has been newly remixed and recomposed together to make one long seamless composition. In the next room, a second quadrophonic speaker setup plays sounds recorded by Mathison in the CCA itself, seeking out the “sweet spots in the building” where the historical properties of the space seem to seep into its acoustic signature.

A further set of speakers in an adjoining corridor broadcasts noises directly from the street outside (during my visit, I could hear the squeal of traffic, distant voices). Finally, in the back room of the space, a wide rectangular screen plays Mathison’s film, Untitled (2018), with its own soundtrack built of field recordings and synthesizer glitches. Each of these “moving parts,” as he puts it, then “interlock” into a signal composition, with the different elements “making space for the other pieces” at different times, creating a sonic arena that the viewer can move through, making one’s own body into a kind of mixing desk.

In the early 80s, Mathison, alongside Akomfrah, Edward George, Reece Auguiste, Lina Gopaul, and others, was a founder member of the Black Audio Film Collective, part of a brace of new collectives formed by Black British artists supported by the Greater London Council and the new Channel 4 (including the Ceddo Film and Video Workshop and the Sankofa Film and Video Collective formed by Julien with Martina Attille, Maureen Blackwood, and Nadine Marsh-Edwards). For Akomfrah’s ground-breaking Handsworth Songs (1986), Mathison acted as set designer, camera operator, sound recordist and composer, building a rich sonic stew from archive recordings of calypso tunes, reggae, brass bands, and street noise, all montaged together and cloaked in space echo in the manner of an hour-long dub mix.

Mathison identifies dub, as a means of processing sound and a form of sonic investigation, as the thread running throughout his work, right up to the present day. Back in the 80s, he would use answerphone tapes to make loops, snatching fragments of sound off the radio or TV before re-recording the sounds onto a second tape deck, manipulating the sound by hand, or using electronic effects in the process. Many of those old tapes, with sleeves vividly illustrated by Mathison using cuttings from newspapers and magazines, frequently overpainted and deliriously collaged, are presented here in one of several vitrines taking up the central area of the gallery. Alongside these tape boxes, there are old sketchbooks, photographs, and graphic scores that look somewhere between Cornelius Cardew’s Treatise, record sleeves by Sun Ra, and the circuit diagram of some impossible machine.

It seems almost extraordinary that after forty years of work, this is Mathison’s first solo exhibition in a UK institution. There’s a great wealth of material here, much of it rich and heady, testament to a restless creative imagination. Across the three rooms and various small peripheral spaces of the CCA, Mathison here makes sound into something tangible, tactile, and highly plastic. The artist who originally trained as a sculptor speaks now of “sculpting sound” and for once the metaphor feels apt. There is a solidity and materiality to it. You can feel this music – in every sense of the word. That dissonant, textural gnarliness never distracts from the strong emotional tugs that rise from the depths of these sonics like so many half-buried memories. The CCA has been reconfigured as the site of an investigation. The methodology, as ever, is dub.

[1]

Read Rob Wilson’s review of Goldsmiths CCA for Architects’

Journal at: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/buildings/assemble-raises-the-roof-on-goldsmiths-centre-for-contemporary-art

Trevor Mathison is an artist, composer, and sound designer and recordist. His sonic practice centres on creating fractured, haunting aural landscapes, integrating existing music, and

has featured in over 30 award-winning films. Mathison was a founding member of the

cinecultural artist collective, The Black Audio Film Collective (BAFC, 1982–1998), where his body of sonic designs defined and situated the Collective’s film and gallery installations. Mathison has continued to work with some of his former collaborators from Black Audio

(John Akomfrah, Lina Gopaul and David Lawson) creating sound design for installations and feature documentaries. Mathison has also founded and been active in a number of other

experimental sonic groups – Dubmorphology, Hallucinator and Flow Motion. He has also been a pioneer of sound installation work.

www.trevormathison.com

Robert Barry is a freelance writer and musician based in London. His most recent book, Compact Disc, was published by Bloomsbury in 2020.

www.writingbyrobertbarry.tumblr.com

www.writingbyrobertbarry.tumblr.com

visit

Trevor Mathison,

From Signal to Decay: Volume 1, curated by Appau Jnr Boakye-Yiadom and Oliver Fuke, runs at Goldsmiths CCA until 18 Sep 2022:

www.goldsmithscca.art/exhibition/trevor-mathison

Closing the exhibition, there will be a vinyl release of Mathison’s music with purge.xxx, the

second event in this ongoing research project, titled From Signal to Decay: Volume 2.

images

all images Installation views, Trevor Mathison From Signal to Decay: Volume 1 at Goldsmiths CCA © Trevor Mathison, 2022. Credit Rob Harris.

publication date

17 August 2022

tags

Martina Attille, Reece Auguiste, John Akomfrah, Assemble, Robert Barry, Maureen Blackwood, Appau Jnr Boakye-Yiadom, Ceddo Film and Video Workshop, Collage, Dubmorphology, Film, Oliver Fuke, Edward George, Goldsmiths CCA, Lina Gopaul, Handsworth Songs, Isaac Julien, Nadine Marsh-Edwards, Trevor Mathison, Music, Patina, Recording, Sankofa Film and Video Collective, Gary Stewart, Sonic, Sound, Strata, Paloma Strelitz

www.goldsmithscca.art/exhibition/trevor-mathison

Closing the exhibition, there will be a vinyl release of Mathison’s music with purge.xxx, the second event in this ongoing research project, titled From Signal to Decay: Volume 2.