Ghosts in the machine for living in: exhibiting horror in architecture

An exhibition at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham brings the fear of the city’s relentless modernising change into the gallery, but once there treats the subject matter with much broader & more nuanced consideration. Looking at how repressed and hidden voices re-emerge within or despite modern urban plans, Will Jennings explores where fear and 20th century architecture meet.

Birmingham is a city in constant change. The city centre is,

as it ever was, a hive of construction and reimagining, with cranes like

vultures overhead, swooping down to pick at carcasses. It is also a city of

imaginaries and storytelling, both in the cultural history of the place – from

cinemas (see 00035) to Peaky Blinders, Mela to metal – but also wrapped up

within the architecture that remains or has been lost, the proposed futures

within evolving place and fixed monuments, and the ghosts of past futures now

compressed within a new story.

That notion of ghosts within the machine for living in is explored in the current exhibition in the city’s Ikon gallery. Horror in the Modernist Block takes on the ambitious task of considering the relationship of horror and post-war urban architectures, though doesn’t set out to pull focus just on Birmingham itself but pan wider into distant territories and places in search of a deeper meaning between fear and suspense with modernist construction.

![]()

It may be the gothic which has become synonymous with the horror genre of film – with roots reaching back to Horace Walpole’s 1764 story The Castle of Otranto and his Gothic revival architectural Strawberry Hill House – but modernism also has a long history of the uncanny and unnerving within its story. In the early years of Hollywood’s rapidly growing horror film industry, 1934’s The Black Cat starring Boris Karloff and Béla Lugosi is set within the glass brick and Bauhaus curves of a modernist home designed by fictional architect Hjalmar Poelzig – a name borrowed from actual Weimar architect Hans Poelzig – whose home is built over the ruins of an Austro-Hungarian fort the protagonist once commandeered.

Horror often deals with such compression of places, stories, or lives trampled into strata by that built above, with hauntings being the foundational past returning into the present, whether as vapour or violence. This exhibition explores both. An opening room of films introduces some of the curatorial themes. BRUTAL (2022), by artist NT, captures night-time Birmingham housing estates with an eerie ambient soundscape, somewhat relying on cliché tropes of post-war housing, fear, and horror suspense.

However, the following film by Ho Tzy Nyen makes clear that we are in no way going to linger on such local or predictable trappings – their Cloud of Unknowing (2011) is a meticulously polished slow journey around and within a Singapore housing block. A cloud slowly envelopes internal spaces and the protagonists we discover – including a man writing at a desk as smoke seeps through his tightly packed bookshelves, a woman sitting alone in silence as her room is slowly engulfed – characters created by the artist to imagine those who once resided inside. As the film progresses, the soundscape becomes vigorously more violent, and a central character akin to a Singaporean Candyman emerges as a representative of the forces inherent within the fabric of the building. Reaching its denouement, smoke floods over the projection screen and into the gallery.

![]()

![]()

Hauntings here are not presumed to be of a single ghostlike figure, but perhaps previous political or ideological ways of being which cannot be removed entirely within postcolonial rebuilding. The tapestry Directorate (2019) by Shezad Dawood is trapped within a tight teak frame, it has woven into it the representation of a modernist swimming pool in Karachi, Pakistan, part of a 1961 complex by Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander which included the US embassy before being downgraded to a consulate only five years later following Islamabad becoming the capital. Later, it was abandoned completely, with the building remaining as an empty legacy of past eras. The wall decoration behind Dawood’s tapestry references a terrazzo pattern, used within the building but also reflecting on the nation’s failed hopes for an export industry in the material.

![]()

Shadows also recur in works by Karachi born artist Seher Shah in Notes from a City Unknown (2021), a portfolio series of screen-prints amalgamating short concrete poems and dark patterns. Riffing off Italo Calvino’s musings on Venice in Invisible Cities, it conjures various readings of New Delhi as a site of hidden tragedy and sectarianism, each page presenting a different city: CITY OF QUIET SOULS; CITY OF THE BORDERLESS FLOWERS; CITY OF SURVEILLANCE; CITY OF 1947. In works elsewhere in Ikon’s spaces, Shah’s Unit Object etchings (2014) transmogrify the well-worn images of Le Corbusier’s Unité d'Habitation buildings, turning the typology into an unidentifiable other, flat but also seeming to leave imprint and cast irregular shadows.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Le Corbusier’s Unité designs also come to mind in works by Amba Sayal-Bennett who forges unexpected but resolutely mid-century spatial arrangements in sculpture and drawing. At an unknown scale, these imaginaries belie a represent of building or landscape, seeming instead to carry within a spiritual residue of a million past urban plans. Such plans were commonly presented as a solution by a pronounced singular (predominantly white male) genius, often Le Corbusier.

The façade of his Unité d'Habitation buildings contain his ergonomic Modular man diagram, based upon his ideal of humankind – male, white, and tall. Similarly, Sayal-Bennett’s ambiguous forms seem to contain within them not only translated plans and diagrams but also skeletal shapes – perhaps compounding that trace of embodied architectural ego but represented through fractured and dissociated bodily components forced into unbuilt modernist form.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Nearby, the steel Tower (2019) by Monika Sosnowska lays collapsed on the floor as if industry reduced to ruin. Within its structure there is a memory of Soviet futurism and hyperboloid forms such as the century old Shukhov Tower, just about still standing in Moscow despite recent plans for demolition and the ideology within which it was constructed itself having collapsed. A carefully and concisely engineered structure which has no room for slack elements or wasted design, each component tightly working for the whole. Unlike this imaginary fragment, Shukhov Tower remains despite, perhaps to spite, the current Russian regime.

![]()

The title of the exhibition, and the early film by NT, may distract a visitor from some of the more interesting underlying elements at play in some of the works. So deeply ingrained are tropes, presumptions, and clichés of both horror modernist blocks that the title may be a distraction from more subtle and nuanced ideas at play across a range of works which often feel forced into a curatorial position. The exhibition does not instil fear so much as an unsettling sense of the uncanny, and it focuses more on an ever-shifting idea of the modern more than having resolute interest in the modernist style.

Both the uncanny and the modern are central to horror and architecture, so perhaps they offer a curatorial framework better suited to the works on show, and their interconnectedness, than the words of the title. “Horror” and “modernist” carry huge power and baggage which seems to wrestle with a gentler and more broadranging commentary at play within the works on show. The city outside is relentlessly undergoing violent acts of physical change, dislocation, and reshaping, and the works in the exhibition might offer more nuanced ways to think about the power, dynamics, and agency such urban processes without hyperbole.

That notion of ghosts within the machine for living in is explored in the current exhibition in the city’s Ikon gallery. Horror in the Modernist Block takes on the ambitious task of considering the relationship of horror and post-war urban architectures, though doesn’t set out to pull focus just on Birmingham itself but pan wider into distant territories and places in search of a deeper meaning between fear and suspense with modernist construction.

fig.i

It may be the gothic which has become synonymous with the horror genre of film – with roots reaching back to Horace Walpole’s 1764 story The Castle of Otranto and his Gothic revival architectural Strawberry Hill House – but modernism also has a long history of the uncanny and unnerving within its story. In the early years of Hollywood’s rapidly growing horror film industry, 1934’s The Black Cat starring Boris Karloff and Béla Lugosi is set within the glass brick and Bauhaus curves of a modernist home designed by fictional architect Hjalmar Poelzig – a name borrowed from actual Weimar architect Hans Poelzig – whose home is built over the ruins of an Austro-Hungarian fort the protagonist once commandeered.

Horror often deals with such compression of places, stories, or lives trampled into strata by that built above, with hauntings being the foundational past returning into the present, whether as vapour or violence. This exhibition explores both. An opening room of films introduces some of the curatorial themes. BRUTAL (2022), by artist NT, captures night-time Birmingham housing estates with an eerie ambient soundscape, somewhat relying on cliché tropes of post-war housing, fear, and horror suspense.

However, the following film by Ho Tzy Nyen makes clear that we are in no way going to linger on such local or predictable trappings – their Cloud of Unknowing (2011) is a meticulously polished slow journey around and within a Singapore housing block. A cloud slowly envelopes internal spaces and the protagonists we discover – including a man writing at a desk as smoke seeps through his tightly packed bookshelves, a woman sitting alone in silence as her room is slowly engulfed – characters created by the artist to imagine those who once resided inside. As the film progresses, the soundscape becomes vigorously more violent, and a central character akin to a Singaporean Candyman emerges as a representative of the forces inherent within the fabric of the building. Reaching its denouement, smoke floods over the projection screen and into the gallery.

figs.ii,iii

Hauntings here are not presumed to be of a single ghostlike figure, but perhaps previous political or ideological ways of being which cannot be removed entirely within postcolonial rebuilding. The tapestry Directorate (2019) by Shezad Dawood is trapped within a tight teak frame, it has woven into it the representation of a modernist swimming pool in Karachi, Pakistan, part of a 1961 complex by Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander which included the US embassy before being downgraded to a consulate only five years later following Islamabad becoming the capital. Later, it was abandoned completely, with the building remaining as an empty legacy of past eras. The wall decoration behind Dawood’s tapestry references a terrazzo pattern, used within the building but also reflecting on the nation’s failed hopes for an export industry in the material.

fig.iv

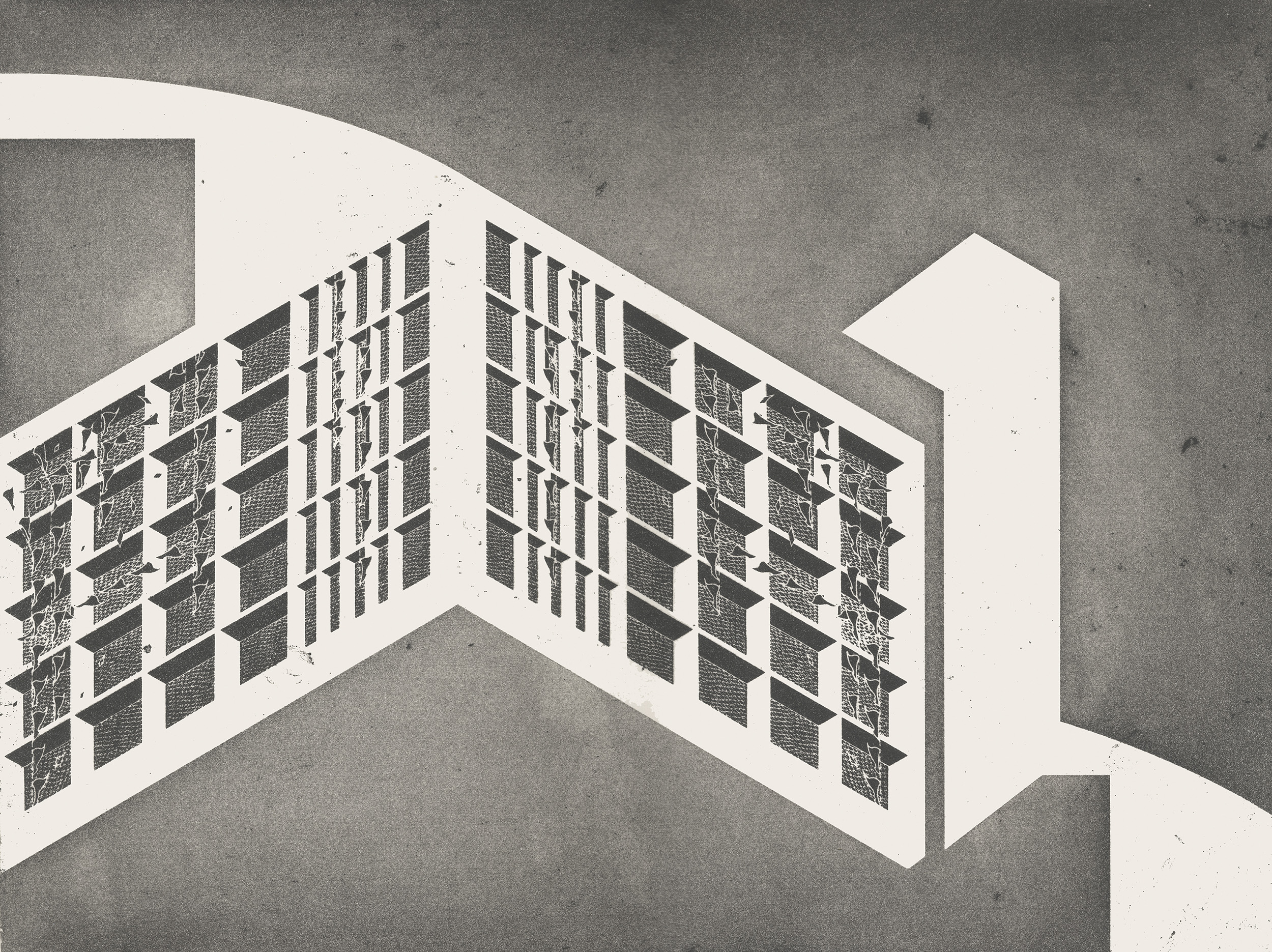

Shadows also recur in works by Karachi born artist Seher Shah in Notes from a City Unknown (2021), a portfolio series of screen-prints amalgamating short concrete poems and dark patterns. Riffing off Italo Calvino’s musings on Venice in Invisible Cities, it conjures various readings of New Delhi as a site of hidden tragedy and sectarianism, each page presenting a different city: CITY OF QUIET SOULS; CITY OF THE BORDERLESS FLOWERS; CITY OF SURVEILLANCE; CITY OF 1947. In works elsewhere in Ikon’s spaces, Shah’s Unit Object etchings (2014) transmogrify the well-worn images of Le Corbusier’s Unité d'Habitation buildings, turning the typology into an unidentifiable other, flat but also seeming to leave imprint and cast irregular shadows.

figs.v-viii

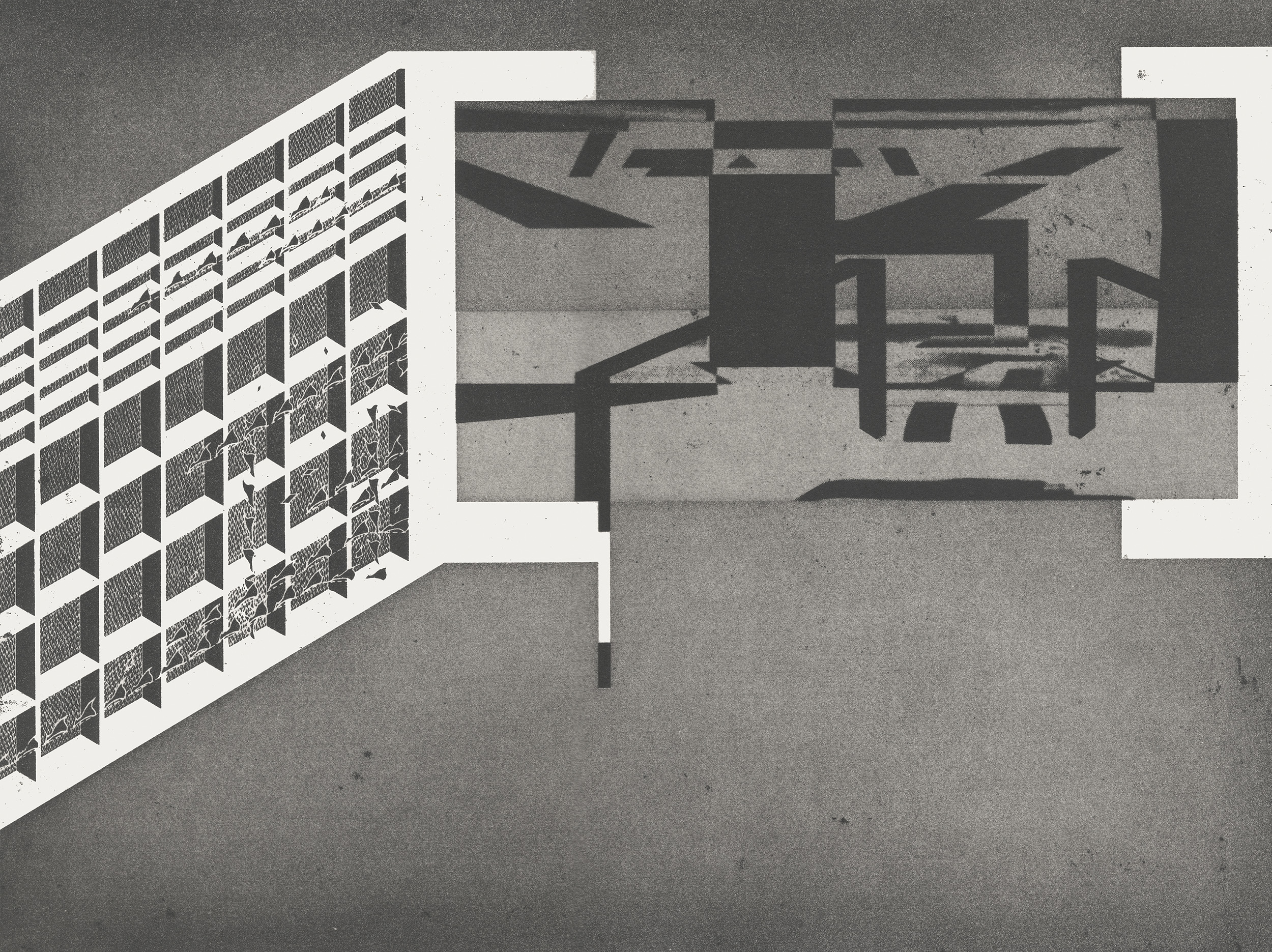

Le Corbusier’s Unité designs also come to mind in works by Amba Sayal-Bennett who forges unexpected but resolutely mid-century spatial arrangements in sculpture and drawing. At an unknown scale, these imaginaries belie a represent of building or landscape, seeming instead to carry within a spiritual residue of a million past urban plans. Such plans were commonly presented as a solution by a pronounced singular (predominantly white male) genius, often Le Corbusier.

The façade of his Unité d'Habitation buildings contain his ergonomic Modular man diagram, based upon his ideal of humankind – male, white, and tall. Similarly, Sayal-Bennett’s ambiguous forms seem to contain within them not only translated plans and diagrams but also skeletal shapes – perhaps compounding that trace of embodied architectural ego but represented through fractured and dissociated bodily components forced into unbuilt modernist form.

figs.ix-xi

Nearby, the steel Tower (2019) by Monika Sosnowska lays collapsed on the floor as if industry reduced to ruin. Within its structure there is a memory of Soviet futurism and hyperboloid forms such as the century old Shukhov Tower, just about still standing in Moscow despite recent plans for demolition and the ideology within which it was constructed itself having collapsed. A carefully and concisely engineered structure which has no room for slack elements or wasted design, each component tightly working for the whole. Unlike this imaginary fragment, Shukhov Tower remains despite, perhaps to spite, the current Russian regime.

fig.xii

The title of the exhibition, and the early film by NT, may distract a visitor from some of the more interesting underlying elements at play in some of the works. So deeply ingrained are tropes, presumptions, and clichés of both horror modernist blocks that the title may be a distraction from more subtle and nuanced ideas at play across a range of works which often feel forced into a curatorial position. The exhibition does not instil fear so much as an unsettling sense of the uncanny, and it focuses more on an ever-shifting idea of the modern more than having resolute interest in the modernist style.

Both the uncanny and the modern are central to horror and architecture, so perhaps they offer a curatorial framework better suited to the works on show, and their interconnectedness, than the words of the title. “Horror” and “modernist” carry huge power and baggage which seems to wrestle with a gentler and more broadranging commentary at play within the works on show. The city outside is relentlessly undergoing violent acts of physical change, dislocation, and reshaping, and the works in the exhibition might offer more nuanced ways to think about the power, dynamics, and agency such urban processes without hyperbole.

Ikon is an internationally acclaimed contemporary art venue situated in central Birmingham. Established in 1964 by a group of artists, Ikon is an educational charity and works to encourage public engagement with contemporary art through exhibiting new work in a context of debate and participation. The gallery programme features artists from around the world and a variety of media is represented, including sound, film, mixed media, photography, painting, sculpture and installation. Ikon’s off-site programme develops dynamic relationships between art, artists and audiences outside the gallery. Projects vary enormously in scale, duration and location,

challenging expectations of where art can be seen and by whom. Education is at the heart of Ikon’s activities, stimulating public interest in and understanding of contemporary visual art. Through a variety of talks, tours, workshops and seminars, Ikon’s Education Team aims to build dynamic relationships with audiences, enabling visitors to engage with, discuss and reflect on contemporary art. ikon-gallery.org

www.ikon-gallery.org

visit

Horror in the Modernist Block is on at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, until 1 May 2023. More information at:

www.ikon-gallery.org/exhibition/horror-in-the-modernist-block

images

fig.i NT, Brutal (2022). HD Video, stereo, 10:42 minutes. Courtesy of Ikon. Photograph © Stuart Whipps.

fig.ii Ho Tzu Nyen, The Cloud of Unknowing (2011).

HD projection, 13 channel sound, smoke machines,

floodlights, show control system

Courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong.

fig.iii

Ho Tzu Nyen, The Cloud of Unknowing (2011).

HD projection, 13 channel sound, smoke machines,

floodlights, show control system. Courtesy Ikon.

Photograph © Stuart Whipps.

fig.iv Shezad Dawood, The Directorate (2019). Tapestry in teak artist’s frame; wallpaper, frame: 159x116cm.

Courtesy Ikon. Photograph © Stuart Whipps.

figs.v Seher Shah, Notes from an Unknown City (2021). Portfolio of 32 screen-prints on paper in custom box, 23x30.5cm.

Courtesy Ikon. Photograph © Stuart Whipps.

fig.vi

Seher Shah, Unit Object (sculpture garden) (2014), Unit Object (landscape view) (2014, & Unit Object (gate) (2014). Etchings, each 53x62.5cm.

Courtesy Ikon. Photograph © Stuart Whipps.

fig.vii Seher Shah, Unit Object (gate) (2014). Etching, 53x62.5cm.

Courtesy of the artist and Glasgow Print Studio.

fig.viii

Seher Shah, Unit Object (landscape view) (2014). Etching, 53x62.5cm.

Courtesy of the artist and Glasgow Print Studio.

fig.ix

Amba Sayal-Bennett, various works (2019-20).

Courtesy Ikon. Photograph © Stuart Whipps.

fig.x Amba Sayal-Bennett,

Soja (2019). Ink, pro-marker and graphite on paper, 21x14.8cm.

Courtesy of the artist.

fig.xi Amba Sayal-Bennett,

Carus (2020). Powder coated mild steel, chemiwood, MDF, resin, velvet, magnets, 133x43x64cm. Courtesy the artist.

fig.ii Monika Sosnowska,

Tower (2019).

Steel, paint, 168x220x215cm

Courtesy of the artist and The Modern Institute/ Toby Webster Ltd., Glasgow

Photo

©

Patrick Jameson.

publication date

05 January 2023

tags

Robert Alexander, Birmingham, The Black Cat, Brutalism, Italo Calvino, Candyman, Castle of Otranto, Shezad Dawood, Demolition, Diagram, Ghost, Horror, Ikon, Invisible Cities, Boris Karloff, Béla Lugosi, Le Corbusier, Masterplan, Modern, Modernism, Richard Neutra, NT, Postcolonialism, Redevelopment, Ho Tzu Nyen, Amba Sayal-Bennett, Seher Shah, Vladimir Shukhov, Shukhov Tower, Monika Sosnowska, Strawberry Hill House, Unité d'Habitation, Uncanny, Urban planning, Horace Walpole

www.ikon-gallery.org/exhibition/horror-in-the-modernist-block