Finding hope within Hurvin Anderson’s barbershops

Painter Hurvin Anderson returns to the subject of barbershops. As spaces of Black culture, community & resilience, through his paintings - which shift between realism, impressionism & abstraction - the artist explores deeper politics & diasporic identity, as Jelena Sofronijevic discovers.

Hurvin

Anderson first painted a barbershop in Birmingham in 2006. For more than

fifteen years, he has returned to and reworked this space, a vital social

setting – particularly for Black men.

Salon Paintings sees Anderson’s studio and barbershop reconstructed at the Hepworth Wakefield in Yorkshire. It is the most comprehensive display of his Barbershop series, alongside which Anderson curates a range of his contemporary British influences. It’s a diverse set – from Duncan Grant’s thick impastos, to Denzil Forrester’s black conte drawings – which sit comfortably together in conversation including Sonia Boyce and Claudette Johnson, two artists he was recently shown alongside at Tate Britain’s recent group exhibition, Life Between Islands.

![]()

![]()

Anderson’s practice has always highlighted connections between communities in Britain and the Caribbean. As a second-generation migrant, whose parents migrated from Jamaica, he practiced in the post-Windrush diaspora of 1980s Britain. Similarly, the barbershop has always migrated. Inua Ellams’ cross-continental play Barbershop Chronicles (2017, then streamed from the National Theatre in 2020) speaks more explicitly to the confessional, gendered nature of these buildings. Anderson’s barbershop, at the heart of Birmingham’s African diaspora, is more particular. But curator Isabella Maidment believes it is a concept that does travel and translates for audiences both in regions further north and at the exhibition’s future homes, Hastings and Norway.

Indeed, the artist has never lived in Jamaica for an extended period; but, with a map of the island on his studio wall, it remains firmly on his mind – and in 2002, he undertook a Caribbean Contemporary Arts residency in the Port of Spain, Trinidad. Indeed, his works speak more to the relationships between both islands; in 2021, Anderson’s Thomas Dane Gallery exhibition featured derelict hotel complexes, abandoned architectures, and artefacts of tourism, economic, and environmental relationships; a theme shared with his contemporary, Ingrid Pollard (see 00042).

![]()

![]()

Fig.iii,iv

Barbershop references the social infrastructure – and architectural design – of this smaller, more intimate space. He tunes into a wider art history too. First seeing his works as abstract, “cubist” paintings, he soon came to see the barbershop as a kind of impressionist bar or cafe, an interior space, in which he invites the viewer to participate.

When putting the intimate on such a large scale, we see the contrasts which characterise his practice. Anderson moves between abstract/figuration and representation, past and present, reality and surrealistic tradition in depicting Caribbean landscapes. Inside, we find a familiar wooden wallpaper, but more, there are mirrors, his first memory of barbershops. Their repetition makes for never-ending halls of mirrors, corridors down which we might reflect on our own positions, and society more widely.

Anderson’s works often incorporate archive and documentary photographs, references to his political influences, including the Civil Rights Movement, Martin Luther King, and Malcolm X. But he never speaks of politics – including the postcolonial context in which his work is read, and curated – directly. Instead, there’s more warmth and humour, personal touches from the barbershop in his titles; a play on “all right in the back,” the familiar refrain from the hairdresser’s chair. More ambiguous, blurred figures – the boxer, perhaps Muhammad Ali – hint again at how the artist dodges addressing questions of his identity.

![]()

![]()

Fig.v,vi

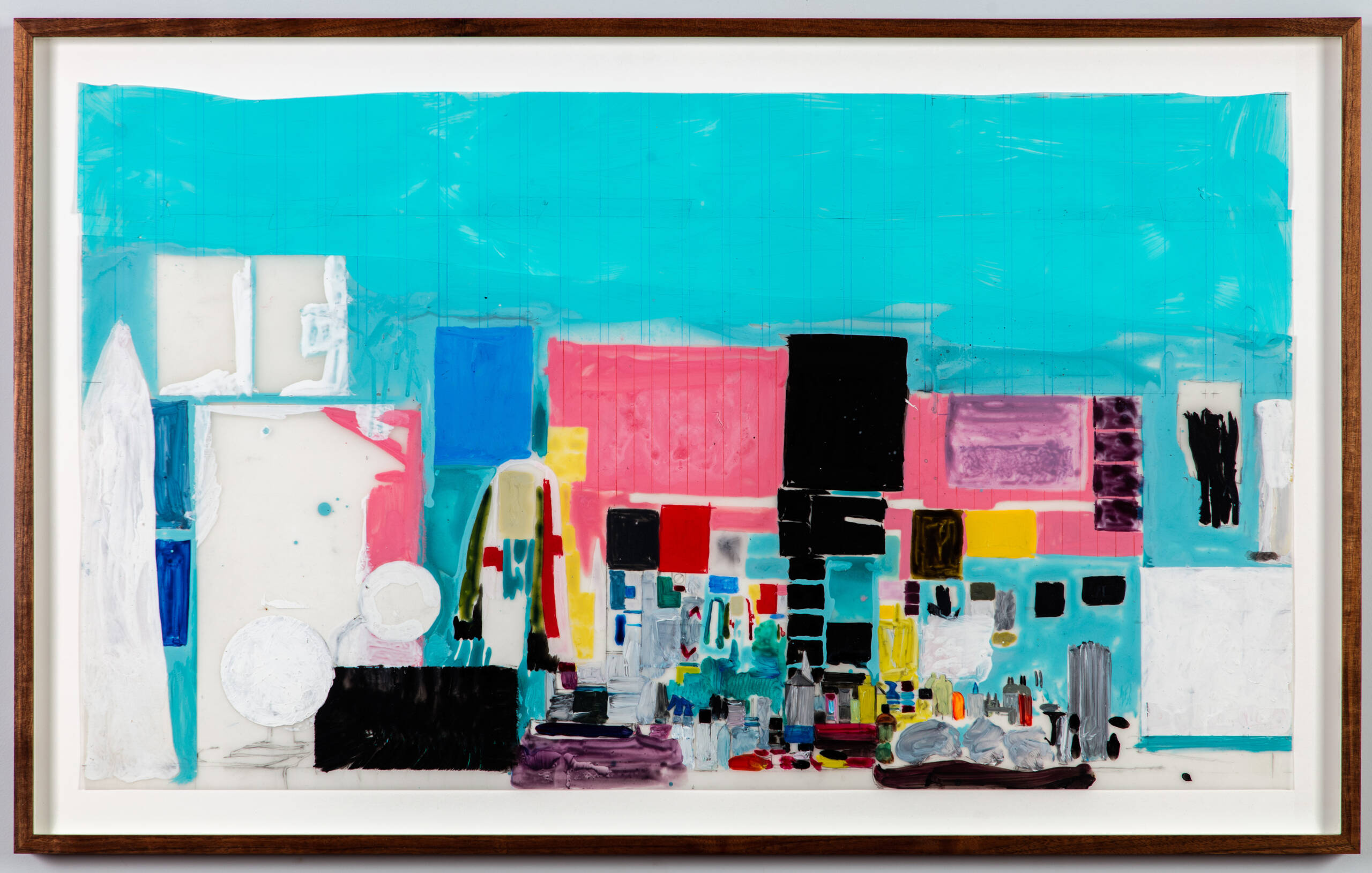

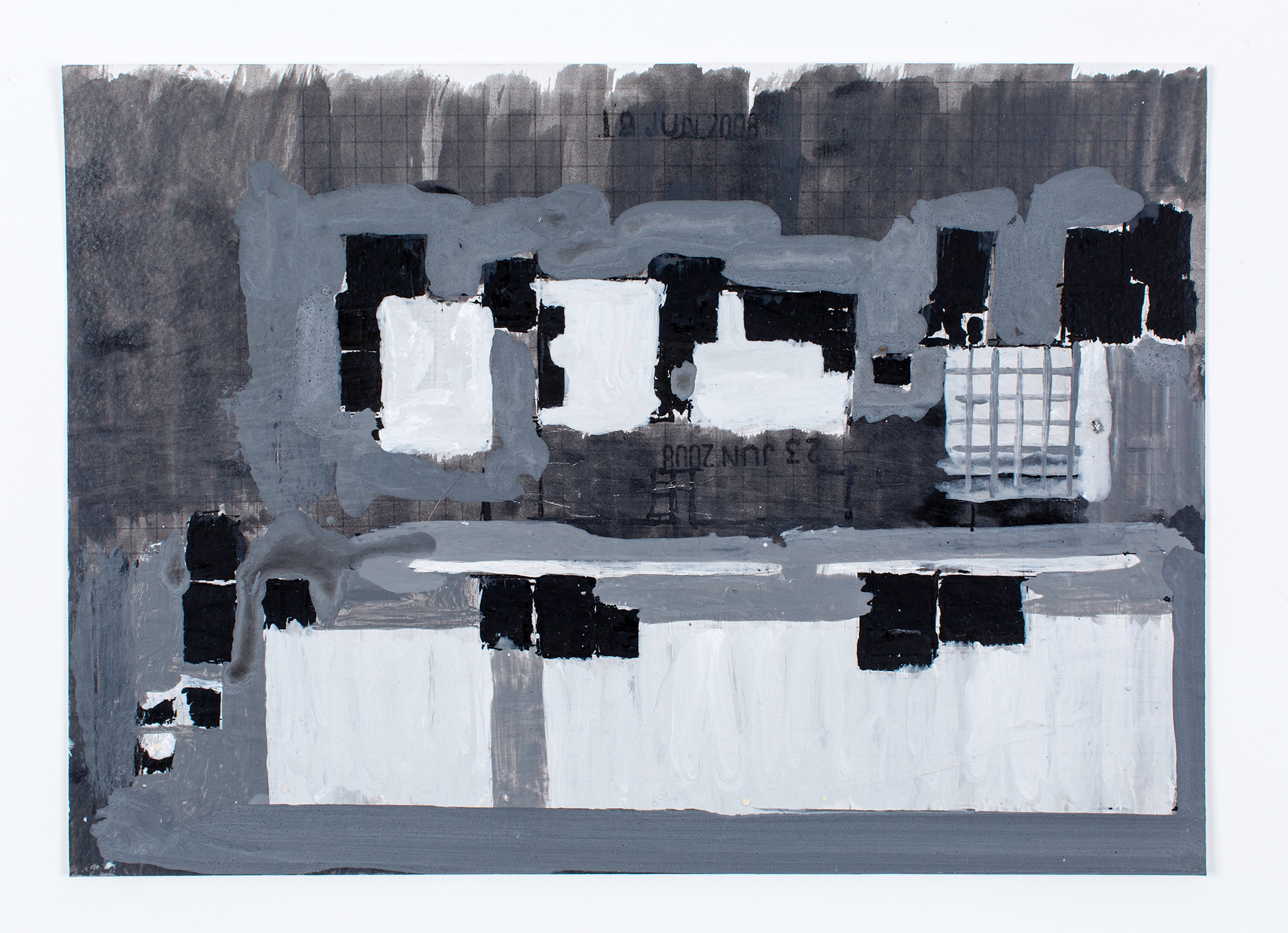

Salon Paintings spans his first studio drawings, to his final work and largest painting from 2022; though we wish to see more of the former, a diverse set in themselves. Alongside the small black-and-white sketches, Anderson offers up surprisingly large, abstract study works, which the artist uses for scale.

Studio Drawing 15 (2006) is a vast acrylic painting; another is comprised of black acrylic lacquered onto layers of drafting film. Indeed, his layering of media – using both canvas and paper, or quick-drying acrylic and slowly-worked oil paints – reflects the plural histories embedded in his practice.

![]()

![]()

Salon Paintings is the artist’s first exhibition since his election to the Royal Academy. Having come of age in the context 1980s Thatcherite Britain, practicing with friends funded through the Enterprise Allowance Scheme, Anderson only came to painting later, when in his 20s. In 2021, Audition (1998) sold for £7.4m – five times its estimate, and the fourth most expensive painting ever sold by a living Black artist. For some conventional art critics, his history has been oversimplified as a working-class success story.

But this overlooks the wider social and economic change that has taken place since Anderson set foot in that barbershop in Birmingham – the collapse of community and rise of individualism. Salon Paintings is thus a hopeful exhibition, that speaks to communities resilient and thriving.

This piece is published in parallel with the 22 June episode from the Windrush Season of EMPIRE LINES, a podcast series by Jelena Sofronijevic, available HERE or below:

Salon Paintings sees Anderson’s studio and barbershop reconstructed at the Hepworth Wakefield in Yorkshire. It is the most comprehensive display of his Barbershop series, alongside which Anderson curates a range of his contemporary British influences. It’s a diverse set – from Duncan Grant’s thick impastos, to Denzil Forrester’s black conte drawings – which sit comfortably together in conversation including Sonia Boyce and Claudette Johnson, two artists he was recently shown alongside at Tate Britain’s recent group exhibition, Life Between Islands.

Fig.i,ii

Anderson’s practice has always highlighted connections between communities in Britain and the Caribbean. As a second-generation migrant, whose parents migrated from Jamaica, he practiced in the post-Windrush diaspora of 1980s Britain. Similarly, the barbershop has always migrated. Inua Ellams’ cross-continental play Barbershop Chronicles (2017, then streamed from the National Theatre in 2020) speaks more explicitly to the confessional, gendered nature of these buildings. Anderson’s barbershop, at the heart of Birmingham’s African diaspora, is more particular. But curator Isabella Maidment believes it is a concept that does travel and translates for audiences both in regions further north and at the exhibition’s future homes, Hastings and Norway.

Indeed, the artist has never lived in Jamaica for an extended period; but, with a map of the island on his studio wall, it remains firmly on his mind – and in 2002, he undertook a Caribbean Contemporary Arts residency in the Port of Spain, Trinidad. Indeed, his works speak more to the relationships between both islands; in 2021, Anderson’s Thomas Dane Gallery exhibition featured derelict hotel complexes, abandoned architectures, and artefacts of tourism, economic, and environmental relationships; a theme shared with his contemporary, Ingrid Pollard (see 00042).

Fig.iii,iv

Barbershop references the social infrastructure – and architectural design – of this smaller, more intimate space. He tunes into a wider art history too. First seeing his works as abstract, “cubist” paintings, he soon came to see the barbershop as a kind of impressionist bar or cafe, an interior space, in which he invites the viewer to participate.

When putting the intimate on such a large scale, we see the contrasts which characterise his practice. Anderson moves between abstract/figuration and representation, past and present, reality and surrealistic tradition in depicting Caribbean landscapes. Inside, we find a familiar wooden wallpaper, but more, there are mirrors, his first memory of barbershops. Their repetition makes for never-ending halls of mirrors, corridors down which we might reflect on our own positions, and society more widely.

Anderson’s works often incorporate archive and documentary photographs, references to his political influences, including the Civil Rights Movement, Martin Luther King, and Malcolm X. But he never speaks of politics – including the postcolonial context in which his work is read, and curated – directly. Instead, there’s more warmth and humour, personal touches from the barbershop in his titles; a play on “all right in the back,” the familiar refrain from the hairdresser’s chair. More ambiguous, blurred figures – the boxer, perhaps Muhammad Ali – hint again at how the artist dodges addressing questions of his identity.

Fig.v,vi

Salon Paintings spans his first studio drawings, to his final work and largest painting from 2022; though we wish to see more of the former, a diverse set in themselves. Alongside the small black-and-white sketches, Anderson offers up surprisingly large, abstract study works, which the artist uses for scale.

Studio Drawing 15 (2006) is a vast acrylic painting; another is comprised of black acrylic lacquered onto layers of drafting film. Indeed, his layering of media – using both canvas and paper, or quick-drying acrylic and slowly-worked oil paints – reflects the plural histories embedded in his practice.

Fig.vii,viii

Salon Paintings is the artist’s first exhibition since his election to the Royal Academy. Having come of age in the context 1980s Thatcherite Britain, practicing with friends funded through the Enterprise Allowance Scheme, Anderson only came to painting later, when in his 20s. In 2021, Audition (1998) sold for £7.4m – five times its estimate, and the fourth most expensive painting ever sold by a living Black artist. For some conventional art critics, his history has been oversimplified as a working-class success story.

But this overlooks the wider social and economic change that has taken place since Anderson set foot in that barbershop in Birmingham – the collapse of community and rise of individualism. Salon Paintings is thus a hopeful exhibition, that speaks to communities resilient and thriving.

This piece is published in parallel with the 22 June episode from the Windrush Season of EMPIRE LINES, a podcast series by Jelena Sofronijevic, available HERE or below:

Hurvin Anderson was born in Birmingham in 1965 to Jamaican parents. He completed his BA at the Wimbledon School of Art in 1994, before receiving his MA from London’s Royal College of Art in 1998. Anderson was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 2017 and his work is represented in public collections around the UK, USA and Europe.

www.thomasdanegallery.com/artists/28

Jelena Sofronijevic is an audio producer & freelance journalist who creates content at the intersections of cultural and political history. They are the producer of EMPIRE LINES, a podcast which uncovers the unexpected flows of empires through art, and historicity, a new series of audio walking tours, exploring how cities got to be the way they are.

www.jelsofron.com

EMPIRE LINES

historicity

www.jelsofron.com

EMPIRE LINES

historicity

visit

Hurvin Anderson: Salon Paintings / Hurvin Anderson Curates is exhibited at Hepworth Wakefield until 5 November 2023.

Further information available at:

www.hepworthwakefield.org/whats-on/hurvin-anderson-salon-paintings

The exhibition will tour to Hastings Contemporary (17 November 2023 – 3 March 2024), Further details

at:

www.hastingscontemporary.org/events/hurvin-anderson-barbershop

Then it will show at Kistefos, Norway (27 April – 13 October 2024):

www.kistefosmuseum.com

images

fig.i

Hurvin Anderson, Miss Jamaica (2021). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Ben Westoby.

fig.ii Hurvin Anderson, Flat Top (2008). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Hugh Kelly.

fig.iii

Hurvin Anderson. Lust for Life (2011). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Eva Herzog.

fig.iv

Hurvin Anderson, Afrosheen (2009). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery.

fig.v

Hurvin Anderson, Is It Ok To Be Black? (2015). A 70th Anniversary Commission for the Arts Council Collection with New Art Exchange, Nottingham and Thomas Dane Gallery, Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London. © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Richard Ivey.

fig.vi

Hurvin Anderson, Studio Drawing 9 (2012). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Richard Ivey.

fig.vii

Hurvin Anderson, Studio Drawing 1 (2006). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Richard Ivey

fig.viii Hurvin Anderson. B.H.B. (2016). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Michael Werner Gallery, New York. Photo: Richard Ivey.

publication date

26 June 2023

tags

Abstract, Hurvin Anderson, Barbers, Barbershop, Barbershop Chronicles, Birmingham, Caribbean, Hastings Contemporary, Identity, Impressionism, Inua Ellams, Kistefos, Painting, Postcolonial, Salon, Social infrastructure, Jelena Sofronijevic, The Hepworth Wakefield, The National Theatre, Thomas Dane Gallery, Windrush

Further information available at:

www.hepworthwakefield.org/whats-on/hurvin-anderson-salon-paintings

The exhibition will tour to Hastings Contemporary (17 November 2023 – 3 March 2024), Further details at:

www.hastingscontemporary.org/events/hurvin-anderson-barbershop

Then it will show at Kistefos, Norway (27 April – 13 October 2024):

www.kistefosmuseum.com