An invitation into the sublime: the imaginary architectures of

Al Held & Minoru Nomata

Exhibitions at both of White Cube’s London galleries invite the viewer into sublime imaginary worlds full of architectural reference & idea. The works of Al Held & Minoru Nomata, both painters with deep relationships to the built environment & man-shaped landscapes, offer beautifully composed but somewhat unsettling alternate realities, as seen by Will Jennings.

Two new White Cube exhibitions present paintings by artists

deeply interested in architecture and structure. Across both the gallery’s

London spaces, visitors can explore imaginary landscapes and constructions that

seem to contain history, theory, and references to architectural moments and

monuments. Both also carry something of a digital ethereality to them, though

all the works are meticulously created through painterly processes it is hard

not to now view the depicted imaginaries as products of technology and AI.

![]()

![]()

In the large Bermondsey HQ of White Cube, the work of American painter Al Held (1928-2005) is presented in the exhibition About Space. It is a deep study of geometry and perspective, following all the rules of renaissance understanding but with a sense of the postmodern baroque, resulting in largescale canvases that suck the viewer into uncanny and otherworldly environments. At White Cube’s St James’ space in Mason’s Yard Japanese painter Minoru Nomata presents Continuum, a dystopian series of unpopulated remnants of a distant modernist hope. Here, amongst abandoned skeletal frameworks, decaying grandeur, and melting nature, it is less another world Nomata has created, more a reconsideration of where our own may be headed.

The works in Al Held’s show cover four and a half decades of the artist’s career, from playful abstract and geometric arrangements from the 1960s in the gallery’s opening space, through to a 9 by 4.5 metre canvas at end of the sequence of spaces, a vast cacophony of landscape and structure akin to a Superstudio X Archigram X Zaha Hadid mashup. Eagle Rock IV (2004) was a work Held was working on aged 75, not for a patron, gallery, or commission, just for his own long-held interest in exploring geometric possibilities. Before the monumental piece which has not been shown publicly before is reached, however, there are countless other virtual worlds to explore.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Al Held was profoundly interested in geometry, hyperspace, the Renaissance, the architecture of Rome, abstract expressionism, postmodernism, and perspectival play. His process began with watercolours, testing arrangements of forms with multiple perspectives before, once finding an emergent composition, moving on to a larger canvas to scale-up the imaginary. 1995’s Four and One Third could be read as a carefully placed boulder on a picturesque lawn leading to a modernist glass architecture, but through the distortions of colour and polygon geometries nothing is certain. Orion from 1991 carries something of a Niemeyer spiral, albeit one detached from gravity with various modernist forms splayed across the uncertain landscape. Roberta’s Trip II is from 1986 and reads as a contortion of infrastructures, folded lengths weaving in and through a more rigid structure with plane surfaces somewhere between structure and collapse, an organised chaos.

There is a clear interest in knowledge not only in art, but also spatial and architectural theory and history. Held also mixed with great architects of the late 20th century period, socially and intellectually. He was often “at loggerheads” with Robert Venturi, while not only did I.M. Pei hang a Held painting in his office for three decades, he selected another to be displayed in the entrance of the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse.

![]()

Eagle Rock IV presents many of the themes present across Held’s decades of work. There is richly shaded colour which clashes like a Bridget Riley, dazzling op art spheres reminiscent of Victor Vasarely, a perspectival vantage over unfolding plains which read like Zaha Hadid’s early 80s paintings, Superstudio-esque gridded structures in the foreground, and an Archigram pop sensibility tying it together with joy. But now, in an age of digital landscapes, metaverses, and artificial realities, the strongest sense within this and other works is a sense of CGI. While the aesthetic may feel as if it’s ready for a virtual reality experience, Held’s practice was deeply rooted in a slow process, delicately tweaking and working elements, angles, and forms until it all felt true to its own world.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Minoru Nomata’s worlds also have a sense of the contemporary digital around them. With disappointing ease it is easy for anybody to now use Dall-E or Midjourney to create somewhat bland, unimaginative but strange architectures and landscapes, and with their soft hue, lack of human presence, and a strange, contorted sense of reality, Nomata’s paintings carry something of the AI about them. Except where AI is flat in both aesthetic and meaning, these paintings are poetic and tragic, and where AI can be created in milliseconds, Nomata’s works are a product of not only a slow painting process, but a life deeply embedded in sci-fi, literature, architecture, electronic music, and consideration of the human experience.

![]()

![]()

Again, in these works there is a presence of architectural history. There is a semblance of Étienne-Louis Boullée’s imaginary spherical cenotaph for Isaac Newton in Nomata’s Continuum 19 (2024), though here it’s precarious and at risk of rolling away with the slightest tremor. The spectre of late 19th century world fairs is present in Imagine 2 (2018), a skeleton of an ironwork tower and wheel above a tented festival. Continuum 1 is a mash of Peter Eisenman and MC Escher, with a staircase seemingly growing like a vine up and around the frame of an unfinished monolith. Continuum 5 carries an uncanny similarity to Charles Burton’s ambitious and speculative 1852 proposition to deconstruct Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace and turn it into a 1000 foot-tall world-first skyscraper. Erich Mendelsohn’s Potsdam observatory, Einstein Tower, can be read in another of Nomata’s structures.

As with Held, art history references also abound. One painting reads like Bruegel’s Tower of Babel further on its journey to total collapse, nearly returned to the landscape it emerged from. In another, Richard Serra-like girders seem to have collapsed onto dead nature. Then anonymous monoliths with a hint of Brâncuși stand proud in a landscape long after their function was forgotten. Continuum 3 reads as an ossified shuttle launch complex, but unknown time and climate seems to have worn whatever it had been supporting into a precarious Boschian stack of forms. A tall canvas shows a near-vertical cliff, but the falling fluid reads more like Robert Smithson’s Asphalt Rundown than anything picturesque, topped off by what might be read as Pripyat fairground’s Ferris wheel teetering on the edge.

![]()

The verticality and towering within many of these works is not accidental. As a child, Nomata recalls watching the Tokyo Tower under construction, slowly pushing its latticework skywards. He also remembers a public bathhouse next to his childhood home, and the thirty metre chimney shooting from it to take steam and sweat into the atmosphere. Then the city around him under constant deconstruction, reimagination, and reordering, especially ahead of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. For much of his career, the artist saw architecture and structures as forms to hold hope, human progress, and as objects he could create and depict to – in his words – shield himself and fill a void.

The new Continuum series at White Cube, however, shows little hope. Instead, there is a postapocalyptic silence, a sense of what might remain long after a cataclysmic moment. The sudden disasters of 9/11 and Fukushima, alongside the comparatively more gradual climate crisis, have all shifted Nomata’s trust in architecture. Where previous painted series caried an optimism, purity, and sci-fi hope, here the artist channels existential threats and destructive human processes through his imagined worlds.

![]()

![]()

An anteroom offers a glimpse into Nomata’s creative process, the way he develops these forms before fixing them in acrylic paint. A vitrine is packed with sketches overlaid by fragments of models and tests of form, this is an architectural process that ends not with a building but an impossible rendering of an increasingly possible future.

“I went to a bar, music was playing in the background,” the artist says through his translator. “It was Brian Eno’s Another Green World,” he recalls, “and I thought ‘wow, this artist is dong something completely different - Eno’s music provoked me into thinking of this nowhere, or a somewhere, a town I don’t know but want to explore.”

![]()

![]()

Figs.xv,xvi

Though drawing on different architectural histories, both Held and Nomata create unknown imaginary worlds that invite exploration. But the works of both also carry a feeling of uncanny familarity and a sense of the sinister, reminding us that fear is an inherent quality of the sublime. The places are attractive at first, the viewer can imagine accepting the invitation to step into the canvases and architectures of both artists, but on deeper inspection see that the worlds within are inhospitable and unsettling, whether through Held’s untethered geometries or Nomata’s apocalyptic despair.

Figs.i,ii

In the large Bermondsey HQ of White Cube, the work of American painter Al Held (1928-2005) is presented in the exhibition About Space. It is a deep study of geometry and perspective, following all the rules of renaissance understanding but with a sense of the postmodern baroque, resulting in largescale canvases that suck the viewer into uncanny and otherworldly environments. At White Cube’s St James’ space in Mason’s Yard Japanese painter Minoru Nomata presents Continuum, a dystopian series of unpopulated remnants of a distant modernist hope. Here, amongst abandoned skeletal frameworks, decaying grandeur, and melting nature, it is less another world Nomata has created, more a reconsideration of where our own may be headed.

The works in Al Held’s show cover four and a half decades of the artist’s career, from playful abstract and geometric arrangements from the 1960s in the gallery’s opening space, through to a 9 by 4.5 metre canvas at end of the sequence of spaces, a vast cacophony of landscape and structure akin to a Superstudio X Archigram X Zaha Hadid mashup. Eagle Rock IV (2004) was a work Held was working on aged 75, not for a patron, gallery, or commission, just for his own long-held interest in exploring geometric possibilities. Before the monumental piece which has not been shown publicly before is reached, however, there are countless other virtual worlds to explore.

Figs.iii-v

Al Held was profoundly interested in geometry, hyperspace, the Renaissance, the architecture of Rome, abstract expressionism, postmodernism, and perspectival play. His process began with watercolours, testing arrangements of forms with multiple perspectives before, once finding an emergent composition, moving on to a larger canvas to scale-up the imaginary. 1995’s Four and One Third could be read as a carefully placed boulder on a picturesque lawn leading to a modernist glass architecture, but through the distortions of colour and polygon geometries nothing is certain. Orion from 1991 carries something of a Niemeyer spiral, albeit one detached from gravity with various modernist forms splayed across the uncertain landscape. Roberta’s Trip II is from 1986 and reads as a contortion of infrastructures, folded lengths weaving in and through a more rigid structure with plane surfaces somewhere between structure and collapse, an organised chaos.

There is a clear interest in knowledge not only in art, but also spatial and architectural theory and history. Held also mixed with great architects of the late 20th century period, socially and intellectually. He was often “at loggerheads” with Robert Venturi, while not only did I.M. Pei hang a Held painting in his office for three decades, he selected another to be displayed in the entrance of the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse.

Fig.vi

Eagle Rock IV presents many of the themes present across Held’s decades of work. There is richly shaded colour which clashes like a Bridget Riley, dazzling op art spheres reminiscent of Victor Vasarely, a perspectival vantage over unfolding plains which read like Zaha Hadid’s early 80s paintings, Superstudio-esque gridded structures in the foreground, and an Archigram pop sensibility tying it together with joy. But now, in an age of digital landscapes, metaverses, and artificial realities, the strongest sense within this and other works is a sense of CGI. While the aesthetic may feel as if it’s ready for a virtual reality experience, Held’s practice was deeply rooted in a slow process, delicately tweaking and working elements, angles, and forms until it all felt true to its own world.

Figs.vii-ix

Minoru Nomata’s worlds also have a sense of the contemporary digital around them. With disappointing ease it is easy for anybody to now use Dall-E or Midjourney to create somewhat bland, unimaginative but strange architectures and landscapes, and with their soft hue, lack of human presence, and a strange, contorted sense of reality, Nomata’s paintings carry something of the AI about them. Except where AI is flat in both aesthetic and meaning, these paintings are poetic and tragic, and where AI can be created in milliseconds, Nomata’s works are a product of not only a slow painting process, but a life deeply embedded in sci-fi, literature, architecture, electronic music, and consideration of the human experience.

Figs.x,xi

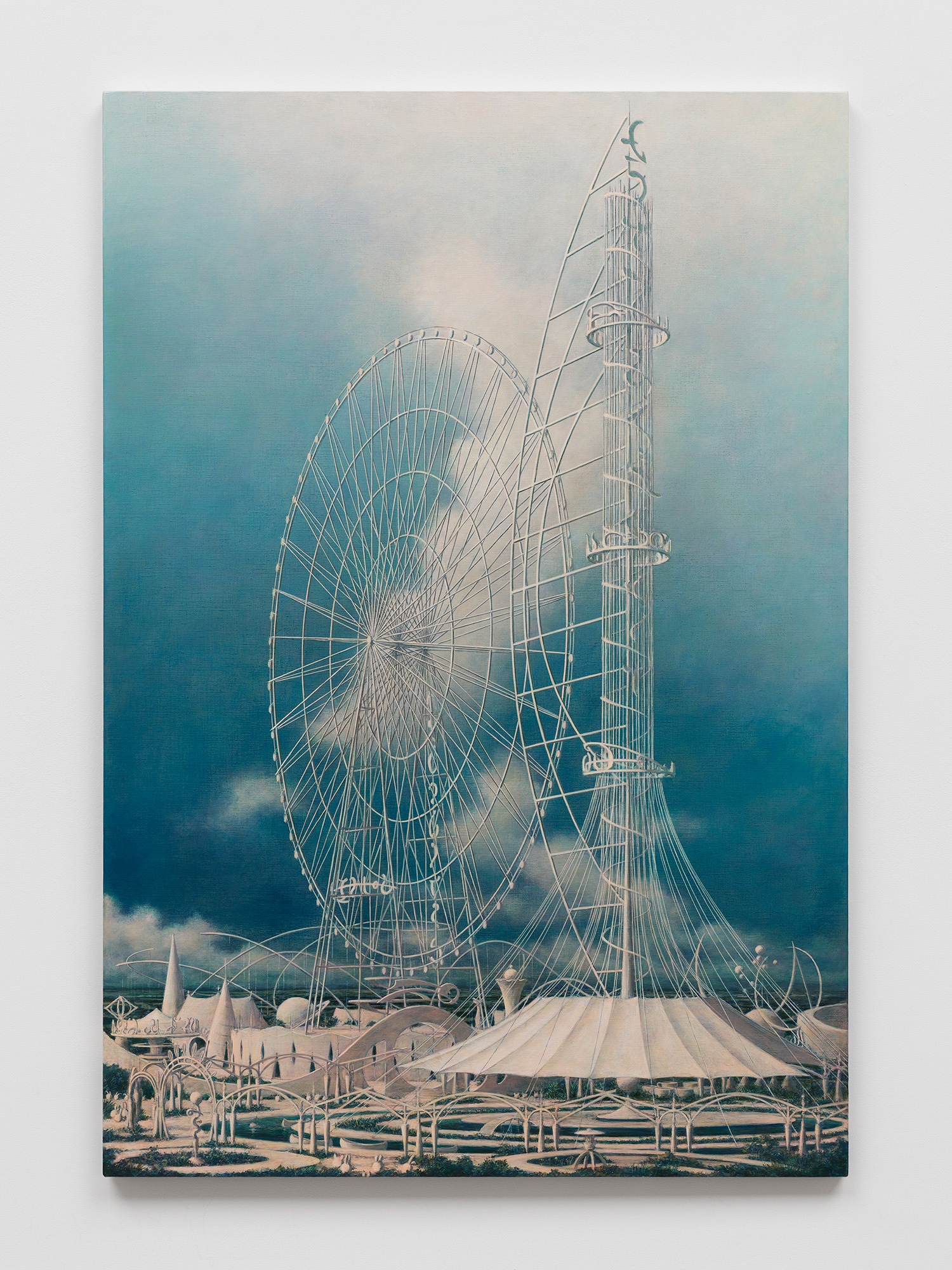

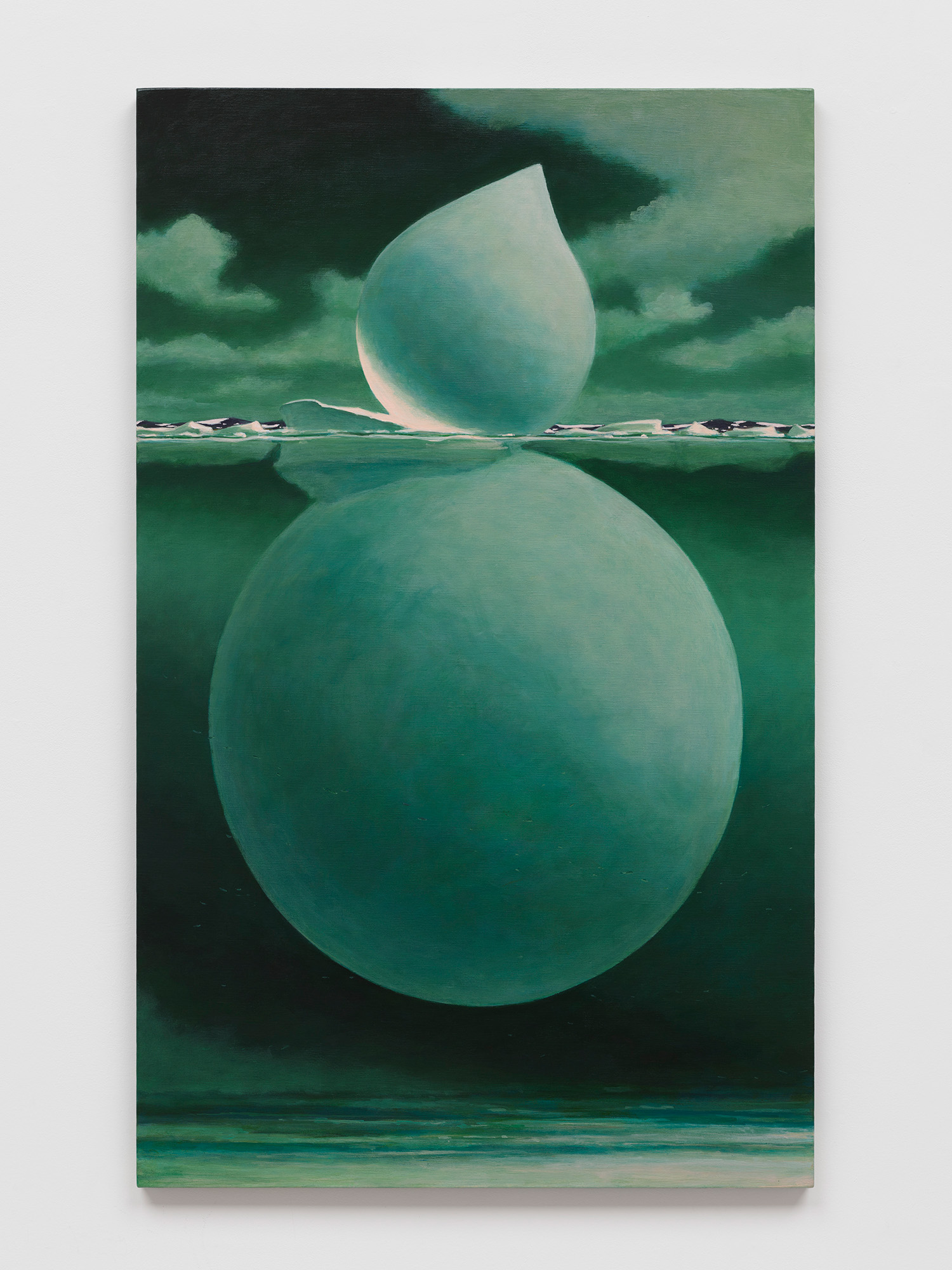

Again, in these works there is a presence of architectural history. There is a semblance of Étienne-Louis Boullée’s imaginary spherical cenotaph for Isaac Newton in Nomata’s Continuum 19 (2024), though here it’s precarious and at risk of rolling away with the slightest tremor. The spectre of late 19th century world fairs is present in Imagine 2 (2018), a skeleton of an ironwork tower and wheel above a tented festival. Continuum 1 is a mash of Peter Eisenman and MC Escher, with a staircase seemingly growing like a vine up and around the frame of an unfinished monolith. Continuum 5 carries an uncanny similarity to Charles Burton’s ambitious and speculative 1852 proposition to deconstruct Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace and turn it into a 1000 foot-tall world-first skyscraper. Erich Mendelsohn’s Potsdam observatory, Einstein Tower, can be read in another of Nomata’s structures.

As with Held, art history references also abound. One painting reads like Bruegel’s Tower of Babel further on its journey to total collapse, nearly returned to the landscape it emerged from. In another, Richard Serra-like girders seem to have collapsed onto dead nature. Then anonymous monoliths with a hint of Brâncuși stand proud in a landscape long after their function was forgotten. Continuum 3 reads as an ossified shuttle launch complex, but unknown time and climate seems to have worn whatever it had been supporting into a precarious Boschian stack of forms. A tall canvas shows a near-vertical cliff, but the falling fluid reads more like Robert Smithson’s Asphalt Rundown than anything picturesque, topped off by what might be read as Pripyat fairground’s Ferris wheel teetering on the edge.

Fig.xii

The verticality and towering within many of these works is not accidental. As a child, Nomata recalls watching the Tokyo Tower under construction, slowly pushing its latticework skywards. He also remembers a public bathhouse next to his childhood home, and the thirty metre chimney shooting from it to take steam and sweat into the atmosphere. Then the city around him under constant deconstruction, reimagination, and reordering, especially ahead of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. For much of his career, the artist saw architecture and structures as forms to hold hope, human progress, and as objects he could create and depict to – in his words – shield himself and fill a void.

The new Continuum series at White Cube, however, shows little hope. Instead, there is a postapocalyptic silence, a sense of what might remain long after a cataclysmic moment. The sudden disasters of 9/11 and Fukushima, alongside the comparatively more gradual climate crisis, have all shifted Nomata’s trust in architecture. Where previous painted series caried an optimism, purity, and sci-fi hope, here the artist channels existential threats and destructive human processes through his imagined worlds.

Figs.xiii,xiv

An anteroom offers a glimpse into Nomata’s creative process, the way he develops these forms before fixing them in acrylic paint. A vitrine is packed with sketches overlaid by fragments of models and tests of form, this is an architectural process that ends not with a building but an impossible rendering of an increasingly possible future.

“I went to a bar, music was playing in the background,” the artist says through his translator. “It was Brian Eno’s Another Green World,” he recalls, “and I thought ‘wow, this artist is dong something completely different - Eno’s music provoked me into thinking of this nowhere, or a somewhere, a town I don’t know but want to explore.”

Figs.xv,xvi

Though drawing on different architectural histories, both Held and Nomata create unknown imaginary worlds that invite exploration. But the works of both also carry a feeling of uncanny familarity and a sense of the sinister, reminding us that fear is an inherent quality of the sublime. The places are attractive at first, the viewer can imagine accepting the invitation to step into the canvases and architectures of both artists, but on deeper inspection see that the worlds within are inhospitable and unsettling, whether through Held’s untethered geometries or Nomata’s apocalyptic despair.

Al Held was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1928 and died in Todi, Italy in 2005. He exhibited extensively throughout his career including solo exhibitions at Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (1966); San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, California and Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC (1968); ICA Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1968); Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, Texas (1969); Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1974); and ICA Boston, Massachusetts (1978), among other museums. He produced major public artworks in prominent cities around the US including Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Washington, DC; New York; and Orlando, Florida. Held’s work features in many museums and public collections including those of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin and Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland. He taught in the graduate programme of the Yale School of Art from 1963–80.

www.alheldfoundation.org

Minoru Nomata (b.1955) lives and works in Tokyo. He studied design at the Tokyo University of the Arts, graduating in 1979 before taking up a position in an advertising agency in the city. After five years Nomata left in order to focus on his painting practice, and in 1986 held his debut exhibition ‘STILL – Quiet Garden’ at the Sagacho Exhibit Space, an alternative gallery in Tokyo run by Kazuko Koike. Further solo exhibitions include White Cube Seoul (2024); Tokyo Opera Art City Gallery (2023); De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, UK (2022); yu-un, Tokyo (2022); The Museum of Modern Art, Gunma, Japan (2010); Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery (2004); and Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo (1993). Until recently, Nomata was a Professor at the Joshibi University of Art and Design in Tokyo.

www.nomataminoru.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.nomataminoru.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

visit

Al Held About Space is exhibited at White Cube Bermondsey until 01 September. Further details available at: www.whitecube.com/gallery-exhibitions/al-held-bermondsey-2024

Minoru Nomata Continuum is exhibited at White Cube Mason’s Yard, London, until 24 August. Further details available at: www.whitecube.com/gallery-exhibitions/minoru-nomata-masons-yard-2024

images

fig.i Al Held. Roberta's Trip II. 1986. Acrylic on canvas. 274.3 x 548.6 cm | 108 x 216 in. © Al Held Foundation / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2024. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis)

fig.ii Minoru Nomata. Continuum-6.

2024.

Acrylic on canvas. 131 x 194.7 cm | 51 9/16 x 76 5/8 in.

© the artist. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis).

fig.iii Al Held. Flow II. 1980. Acrylic on canvas. 274.3 x 548.6 cm | 108 x 216 in. © Al Held Foundation / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2024. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis).

figs.iv,vii,ix Al Held 'About Space', White Cube Bermondsey 27 June – 1 September 2024 © Al Held Foundation / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2024. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis).

fig.v Al Held. Orion V. 1991. Acrylic on canvas 274.3 x 487.7 cm | 108 x 192 in. © Al Held Foundation / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2024. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis).

fig.vi Al Held. Eagle Rock IV. 2004. Acrylic on canvas. 457.2 x 914.4 cm | 180 x 360 in. © Al Held Foundation / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2024. Photo © White Cube (Ollie Hammick).

fig.viii Al Held. Black Nile VII. 1974. Acrylic on canvas. 335.3 x 609.6 cm | 132 x 240 in. © Al Held Foundation / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2024. Photo © White Cube (Christopher Burke).

fig.x Minoru Nomata. Continuum-19.

2024.

Acrylic on canvas. 45.6 x 53.5 cm | 17 15/16 x 21 1/16 in.

© the artist. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis).

fig.xi Minoru Nomata. Imagine-2.

2018.

Acrylic on canvas. 130.5 x 89.5 cm | 51 3/8 x 35 1/4 in.

© the artist. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis).

figs.xii,xiii Al Held 'About Space', White Cube Bermondsey 27 June – 1 September 2024 © Al Held Foundation / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2024. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis).

fig.xiv Minoru Nomata. Continuum-12.

2024.

Acrylic on canvas. 130.7 x 80.7 cm | 51 7/16 x 31 3/4 in.

© the artist. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis).

fig.xv Minoru Nomata. Continuum-15.

2024.

Acrylic on canvas. 56.7 x 162.3 cm | 22 5/16 x 63 7/8 in.

© the artist. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis).

fig.xvi Al Held. See Through IV. 2002. Acrylic on canvas. 274.3 x 274.3 cm | 108 x 108 in. © Al Held Foundation / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2024. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis).

publication date

11 July 2024

tags

9/11, AI, Archigram, Étienne-Louis Boullée, Colour, Constantin Brâncuși, Pieter Bruegel, Charles Burton, Climate, Crisis, Decay, Destruction, Peter Eisenman, Emptiness, Brian Eno, MC Escher, Exploration, Fukushima, Geometry, Zaha Hadid, Al Held, Hyperspace, Will Jennings, Landscape, Erich Mendelsohn, Oscar Niemeyer, Minoru Nomata, Painting, Joseph Paxton, IM Pei, Post apocalyptic, Reality, Bridget Riley, Richard Serra, Sinister, Robert Smithson, Sublime, Superstudio, Tokyo, Tokyo Tower, Tower, Twin Towers, Victor Vasarely, Robert Venturi, White Cube

Minoru Nomata Continuum is exhibited at White Cube Mason’s Yard, London, until 24 August. Further details available at: www.whitecube.com/gallery-exhibitions/minoru-nomata-masons-yard-2024