The origins & afterlife of tarot & the Warburg Institute

The Warburg Institute’s London HQ is a Charles Holden-designed block inside which their library, archive & educational facilities explore the history of cultural history & the rold of images in society. It has recently been renovated by Haworth Tompkins architects who have inserted new spaces into an unused central atrium & improved the building throughout. Will Jennings visited to see how they have also made the building more accessible to the public, including the introduction of an exhibition space which has just opened a presentation on the history of tarot cards, drawing from the archive of the institution & Aby Warburg, its founder.

Much of London is hidden away. Concealed behind anonymous façades

camouflaged into the brick and rhythm of the city’s dense urban fabric are

countless fascinating interiors, rich in history, intrigue, and architectural interest

often not only inaccessible but unknown to the public. Such a place is the

Warburg Institute, proudly standing in the middle of Bloomsbury it is a

world-leading centre for the study of art, culture, and the role of images affiliated to the

University of London’s School of Advanced Study, the UK’s national centre for

the promotion and facilitation of research into the humanities.

In a few square kilometres of London saturated in centres of academia and archive – the UCL campus to the north, the British Museum to the south, and nearby the towering monolith of Senate House – the Warburg has perhaps been little known outside of the academics and historians who rely on its rich collection of books and material. With a new renovation and expansion from architects Haworth Tompkins, incorporating a new public exhibition space, the institution is now set to become a feature on the capital’s cultural map to a wider audience.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Inside is a rich archive of books, photography, and ephemera across a wide range of arts and sciences, celebrating intersectional thinking and the unexpected in humanities. The Warburg didn’t start in London, however, but is rooted in Hamburg, founded by the pioneering historian Aby Warburg at the turn of the 20th century. A scholar who studied the history of art in Bonn, Florence, and Strasbourg, Warburg felt limited by academic discourse and a stylistic approach to the history of art. Developing an interest in the role of images in the understanding of the afterlife, Warburg developed his scholarly path independently and away from existing academia – not least because increasingly antisemitic institutions would not work with the Warburg, member of a great Jewish banking family.

Warburg had been developing his private collection of books and artefacts, and in 1926 housed them within a new building, the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg [KBW], with a recognisable elliptical reading room. Over the years the place built in stature and staffing, growing from a library to institute and publisher, establishing the collection in Hamburg even after Aby Warburg died in 1929. In 1933, however, with the Nazis in power and the numerous Jewish members of staff and scholarly network reading the political direction, the institute evacuated entirely, with the family, supporters, collections, and furniture sent to England where it was housed in changing London locations until, with the collection having been gifted in trust to the University of London, a new permanent Charles Holden-designed Bloomsbury home was founded in 1958.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Over the years, the building has been home to celebrated researchers and historians, many Jewish with a strong connection to the only cultural institution rescued from Nazi Germany still intact and open today, including Austrian émigré Ernst Gombrich, author of The Story of Art (1950) started at the institution as a research assistant in 1936 and left as Director 40 years later. The 60,000 books rescued from Aby Warburg’s Hamburg collection have been added to with 300,000 more examining the history of human civilisation. These include not only the traditional canon of painting, sculpture, architecture, and languages, but also early cultures, political history, religion, and magic (and a large section on historical international festivals) all packed in open shelves encouraging intentional and accidental connections and questions. As well as books, vast private archives and 400,000 photographs are all squeezed into the Bloomsbury HQ, including: Ernst Gombrich’s working archive; a 1587 book on comets and divination that is the only surviving copy in the world; a unique album of Weimar-era Notgeld emergency banknotes; a 1489 copy of text by Abu Mashar, the great author on Islamic astronomy; tens of thousands of letters to and from Aby Warburg, from people including Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin; a library of historical cookery books; and Lady Frieda Harris’ 81 original paintings for the so-called Thoth Tarot, designed in the early 1940s with the infamous magus Aleister Crowley. It is a rich and eclectic collection.

It meant, however, that over the years the building had started creaking and becoming increasingly unfit for purpose. Though the building had been largely unchanged from Charles Holden’s original plans – original terrazzo floors, steel windows and balustrades, hardwood joinery remained within an immaculately detailed interior – changes of functions meant the building didn’t quite serve the institution’s needs. Architects Haworth Tompkins were commissioned for a major overhaul of the Warburg, re-opening in late 2024 with not only a repaired roof and modern services but also a major polish to the entrance area and routes through the building, a refurbished reading room (retaining Holden’s shelving), reconfigured spaces made more suitable for modern teaching, and a new arrangement of the many kilometres of library stacks.

![]()

![]()

![]()

In a book published to mark the re-opening of the building, architect Graham Haworth states that Charles Holden’s classical modernist 1950s building “was quite poorly received upon completion and was seen to be of a low architectural standard by the architectural press,” but adds that “Time has been a kinder critic and today the building is seen as an intact example of its period, and is considered by those that use it to be easy and comfortable to work in.” Their work was to restore Holden’s clarity, but also add new layers to suit today’s needs, and as part of this Haworth Tompkins added new spaces into the institute, essentially dropping a new architectural structure into the previously unused spaces of the courtyard and lightwell, as well as providing two additional floors of accomodation.

![]()

![]()

![]()

In 2013 the same architects were responsible for a largescale upgrade to another historic London archives, The London Library, a labyrinth of 1 million books on open stacks in a jigsaw of buildings leading off St. James’s Square. There, Haworth Tompkins carried out a similar action, glazing over the unusued central lightwell to create a grand Reading Room, tying the building together with a new function at its heart. In the Warburg, the ground level of the former courtyard is now an auditorium (which can hold 140 seats and, in the corner, is home to Ernst Gombrich’s Steinberg piano) while the floor below, similar to the London Library, is a reading room for the special collections.

The original Hamburg Warburg building was designed by Gerhard Langmaack according to plans by Fritz Schumacher, and at its heart was a reading and lecture room elliptical in plan. This form was derived from the Warburgian intersection of science and humanities, speaking to the astronomical movement of planets as well as a personal symbol of both the human psyche and rational thinking (the archive includes a manuscript and diagram by Albert Einstein explaining the significance of the architectural ellipse for Warburg). The new Haworth Tompkins auditorium references the form, with a polished concrete ellipse within the ceiling of the rectangular plan, offering a false oculus.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Outside of the auditorium is the Kythera Gallery, a new 185 square metres of public exhibition space, not cut off from the corridor but opened up with simple partition panels, meaning that the curated exhibitions, which will relate to the research and archive of the institution, are not separate from but central to the daily work and activities of the place and its members. The gallery soft-launched late last year with a presentation of artefacts from the Warburg collection, but it has now opened with its first thematically curated, ticketed exhibition, Tarot: Origins & Afterlives.

Ideas around the occult sciences, esoteric practices, and tarot are rife in the contemporary art world, especially amongst emerging and recently graduated Gen-Z artists, but there is a much deeper history which Aby Warburg was similarly deeply interested in. Warburg was amongst the first modern scholars of tarot cards, drawn to how the cards – which evolved from a 15th century card game into a delivery system for divine and occult wisdom by the 19th century – straddled astrology and iconography.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The exhibition is rooted around items from the Warburg’s archive, a series of fascinating paintings for the Thoth Tarot, created by Frieda Harris in collaboration with the notorious occultist Aleister Crowley in the 1930s and 1940s. It started for Aby Warburg in the 1890s, when he began studies into the afterlife of antiquity within Italian Renaissance painting, a research project that two decades later led to his discovery of tarot. Then he began acquiring sets and deepening his research into magic and the occult, creating the framework for continuing research that seeks to map the centuries-long history of tarot cards and their relationship to astrology and art.

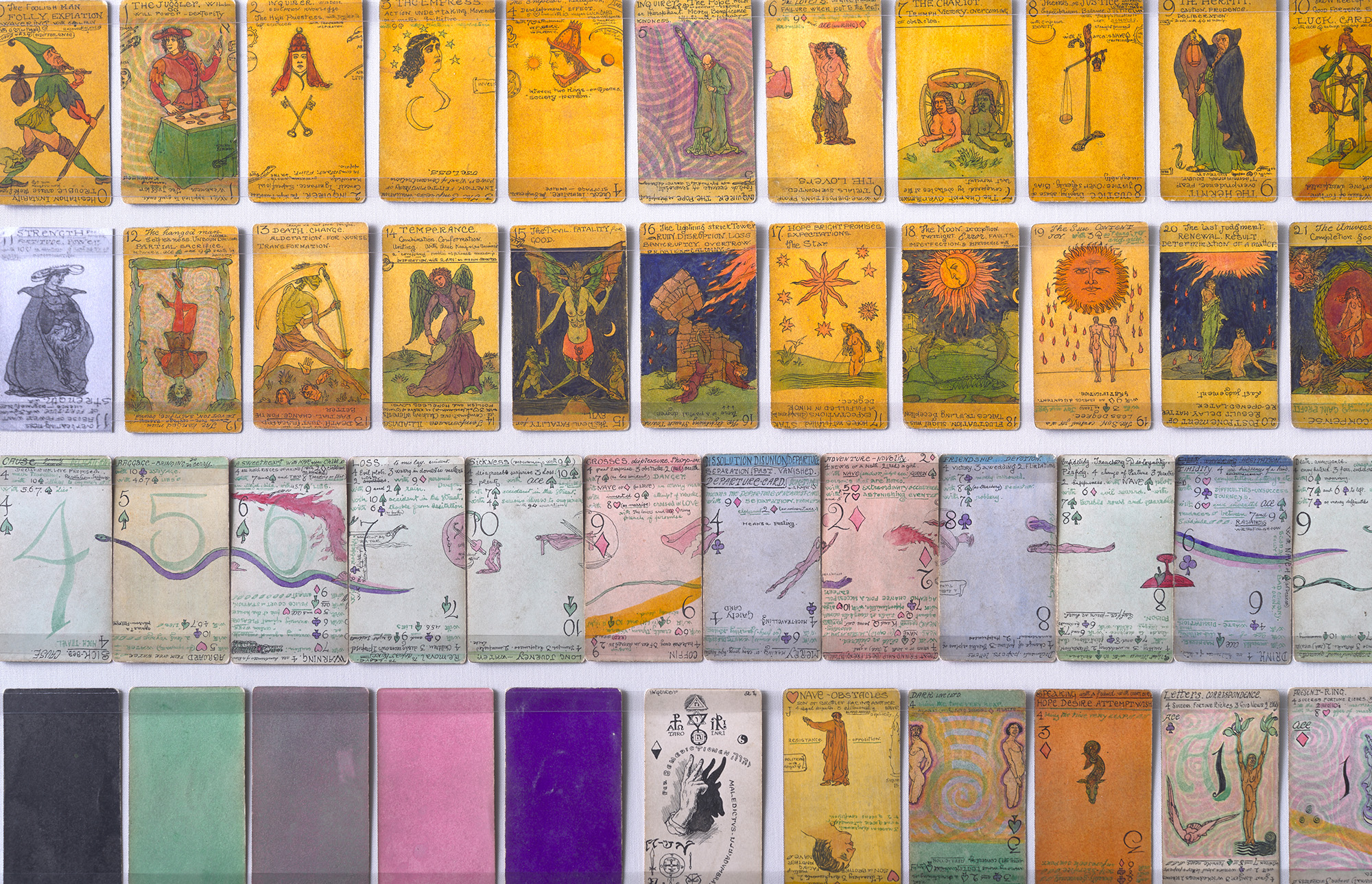

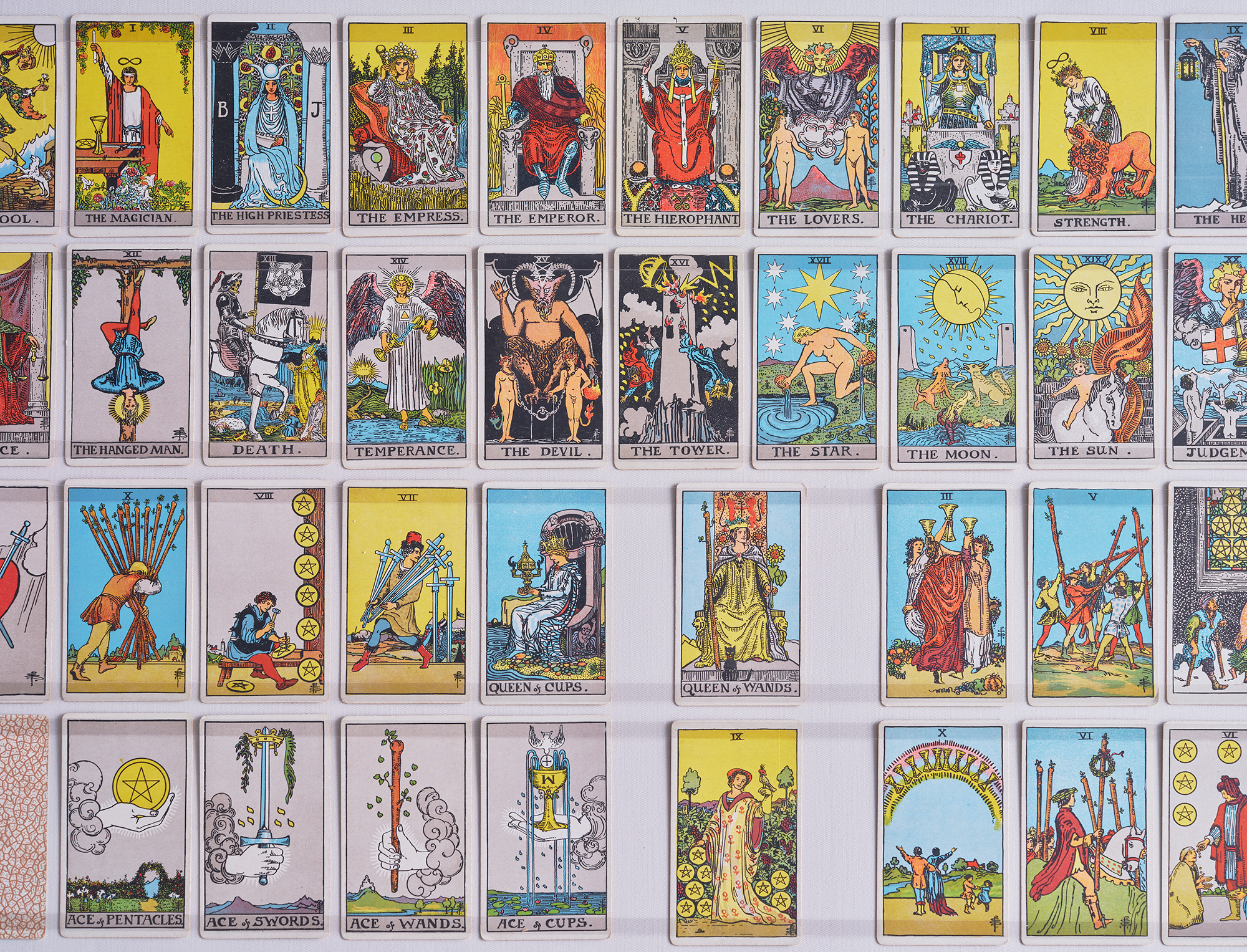

The installation tracks that history, hinging on the late 1800s when esoteric tarot reached Britain from France, playing a role within secret organisations including the likes of Crowley and A.E. Waite. Examples of works by artists including a circa 1906 hand-painted deck by artist and mystic Austin Osman Spare, and Pamela Colman Smith’s from 1909, inspired from 15th century deck, offer rich early examples of modern, occultist tarot.

![]()

![]()

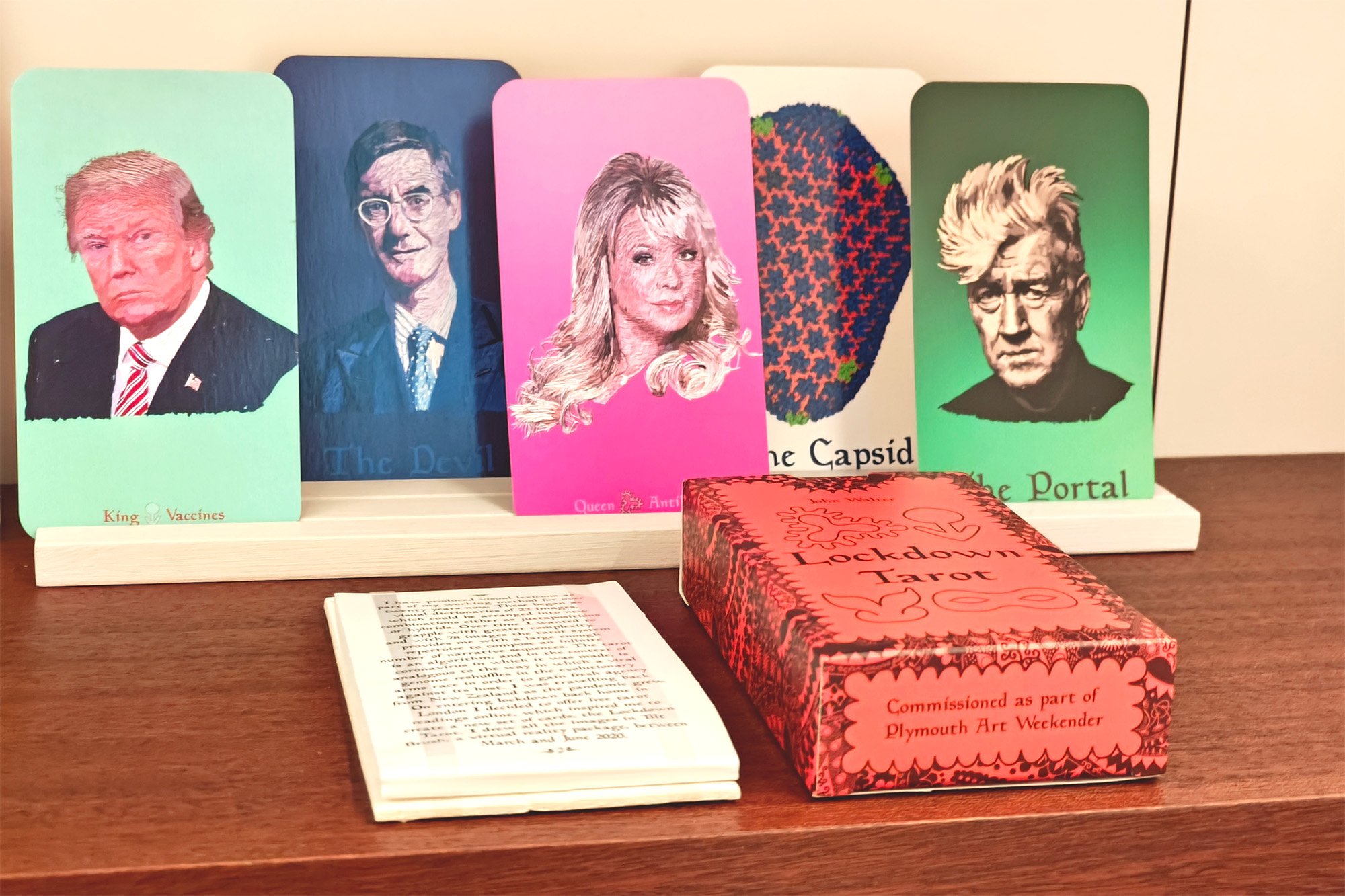

The narrative continues through Italo Calvino’s 1973 novel, The Castle of Crossed Destinies, inspired by arrangements of tarot cards, and leads through to more recent artistic interpretations and uses of tarot, including Suzanne Treister’s Hexen series that map all today’s ecological, scientific, and political issues into richly presented tarot works. Themes include the data industrial complex, social media, industrial ecology, quantum computing, environmental activisim and the history of the web. The final room is an enclosed Tarotkammer, presenting Treister’s pack alongside others by contemporary practitioners, including a set from John Walter combining tarot with queer sexual history, and Plastique Fantastique’s set drawing from memes and modern day tech-infused ecologies.

![]()

![]()

The Warburg has long been a place London’s artist’s have been drawn to for research into unexpected visual and social histories, whether discovering it through Gombrich’s The Story of Art or through specific needs of particular, niche research. Katy Hessel, author of recent book The History of Art Without Men, describes the Warburg as “like no other, with one of the most imaginative, inventive and brilliant libraries in the world,” while Maria Balshaw, the Director of Tate, has described it as “London’s best kept secret.”

Now, it is less of a secret, with Charles Holden’s architecture respectfully refurbished and added to by Haworth Tompkins and more open to the public than ever before. With a cultural programme – which will include future exhibitions on Art & the Book and a major new film commission from founding-member of the Black Audio Film Collective, Edward George – it is also a place where that research seeps into the city a bit more, revealing slightly more of the energy of London concealed behind polite brick façades.

![]()

![]()

In a few square kilometres of London saturated in centres of academia and archive – the UCL campus to the north, the British Museum to the south, and nearby the towering monolith of Senate House – the Warburg has perhaps been little known outside of the academics and historians who rely on its rich collection of books and material. With a new renovation and expansion from architects Haworth Tompkins, incorporating a new public exhibition space, the institution is now set to become a feature on the capital’s cultural map to a wider audience.

figs.i-iii

Inside is a rich archive of books, photography, and ephemera across a wide range of arts and sciences, celebrating intersectional thinking and the unexpected in humanities. The Warburg didn’t start in London, however, but is rooted in Hamburg, founded by the pioneering historian Aby Warburg at the turn of the 20th century. A scholar who studied the history of art in Bonn, Florence, and Strasbourg, Warburg felt limited by academic discourse and a stylistic approach to the history of art. Developing an interest in the role of images in the understanding of the afterlife, Warburg developed his scholarly path independently and away from existing academia – not least because increasingly antisemitic institutions would not work with the Warburg, member of a great Jewish banking family.

Warburg had been developing his private collection of books and artefacts, and in 1926 housed them within a new building, the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg [KBW], with a recognisable elliptical reading room. Over the years the place built in stature and staffing, growing from a library to institute and publisher, establishing the collection in Hamburg even after Aby Warburg died in 1929. In 1933, however, with the Nazis in power and the numerous Jewish members of staff and scholarly network reading the political direction, the institute evacuated entirely, with the family, supporters, collections, and furniture sent to England where it was housed in changing London locations until, with the collection having been gifted in trust to the University of London, a new permanent Charles Holden-designed Bloomsbury home was founded in 1958.

figs.iv-vii

Over the years, the building has been home to celebrated researchers and historians, many Jewish with a strong connection to the only cultural institution rescued from Nazi Germany still intact and open today, including Austrian émigré Ernst Gombrich, author of The Story of Art (1950) started at the institution as a research assistant in 1936 and left as Director 40 years later. The 60,000 books rescued from Aby Warburg’s Hamburg collection have been added to with 300,000 more examining the history of human civilisation. These include not only the traditional canon of painting, sculpture, architecture, and languages, but also early cultures, political history, religion, and magic (and a large section on historical international festivals) all packed in open shelves encouraging intentional and accidental connections and questions. As well as books, vast private archives and 400,000 photographs are all squeezed into the Bloomsbury HQ, including: Ernst Gombrich’s working archive; a 1587 book on comets and divination that is the only surviving copy in the world; a unique album of Weimar-era Notgeld emergency banknotes; a 1489 copy of text by Abu Mashar, the great author on Islamic astronomy; tens of thousands of letters to and from Aby Warburg, from people including Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin; a library of historical cookery books; and Lady Frieda Harris’ 81 original paintings for the so-called Thoth Tarot, designed in the early 1940s with the infamous magus Aleister Crowley. It is a rich and eclectic collection.

It meant, however, that over the years the building had started creaking and becoming increasingly unfit for purpose. Though the building had been largely unchanged from Charles Holden’s original plans – original terrazzo floors, steel windows and balustrades, hardwood joinery remained within an immaculately detailed interior – changes of functions meant the building didn’t quite serve the institution’s needs. Architects Haworth Tompkins were commissioned for a major overhaul of the Warburg, re-opening in late 2024 with not only a repaired roof and modern services but also a major polish to the entrance area and routes through the building, a refurbished reading room (retaining Holden’s shelving), reconfigured spaces made more suitable for modern teaching, and a new arrangement of the many kilometres of library stacks.

figs.viii-x

In a book published to mark the re-opening of the building, architect Graham Haworth states that Charles Holden’s classical modernist 1950s building “was quite poorly received upon completion and was seen to be of a low architectural standard by the architectural press,” but adds that “Time has been a kinder critic and today the building is seen as an intact example of its period, and is considered by those that use it to be easy and comfortable to work in.” Their work was to restore Holden’s clarity, but also add new layers to suit today’s needs, and as part of this Haworth Tompkins added new spaces into the institute, essentially dropping a new architectural structure into the previously unused spaces of the courtyard and lightwell, as well as providing two additional floors of accomodation.

figs.xi-xiii

In 2013 the same architects were responsible for a largescale upgrade to another historic London archives, The London Library, a labyrinth of 1 million books on open stacks in a jigsaw of buildings leading off St. James’s Square. There, Haworth Tompkins carried out a similar action, glazing over the unusued central lightwell to create a grand Reading Room, tying the building together with a new function at its heart. In the Warburg, the ground level of the former courtyard is now an auditorium (which can hold 140 seats and, in the corner, is home to Ernst Gombrich’s Steinberg piano) while the floor below, similar to the London Library, is a reading room for the special collections.

The original Hamburg Warburg building was designed by Gerhard Langmaack according to plans by Fritz Schumacher, and at its heart was a reading and lecture room elliptical in plan. This form was derived from the Warburgian intersection of science and humanities, speaking to the astronomical movement of planets as well as a personal symbol of both the human psyche and rational thinking (the archive includes a manuscript and diagram by Albert Einstein explaining the significance of the architectural ellipse for Warburg). The new Haworth Tompkins auditorium references the form, with a polished concrete ellipse within the ceiling of the rectangular plan, offering a false oculus.

figs.xiv-xvi

Outside of the auditorium is the Kythera Gallery, a new 185 square metres of public exhibition space, not cut off from the corridor but opened up with simple partition panels, meaning that the curated exhibitions, which will relate to the research and archive of the institution, are not separate from but central to the daily work and activities of the place and its members. The gallery soft-launched late last year with a presentation of artefacts from the Warburg collection, but it has now opened with its first thematically curated, ticketed exhibition, Tarot: Origins & Afterlives.

Ideas around the occult sciences, esoteric practices, and tarot are rife in the contemporary art world, especially amongst emerging and recently graduated Gen-Z artists, but there is a much deeper history which Aby Warburg was similarly deeply interested in. Warburg was amongst the first modern scholars of tarot cards, drawn to how the cards – which evolved from a 15th century card game into a delivery system for divine and occult wisdom by the 19th century – straddled astrology and iconography.

figs.xvii-xix

The exhibition is rooted around items from the Warburg’s archive, a series of fascinating paintings for the Thoth Tarot, created by Frieda Harris in collaboration with the notorious occultist Aleister Crowley in the 1930s and 1940s. It started for Aby Warburg in the 1890s, when he began studies into the afterlife of antiquity within Italian Renaissance painting, a research project that two decades later led to his discovery of tarot. Then he began acquiring sets and deepening his research into magic and the occult, creating the framework for continuing research that seeks to map the centuries-long history of tarot cards and their relationship to astrology and art.

The installation tracks that history, hinging on the late 1800s when esoteric tarot reached Britain from France, playing a role within secret organisations including the likes of Crowley and A.E. Waite. Examples of works by artists including a circa 1906 hand-painted deck by artist and mystic Austin Osman Spare, and Pamela Colman Smith’s from 1909, inspired from 15th century deck, offer rich early examples of modern, occultist tarot.

figs.xx,xxi

The narrative continues through Italo Calvino’s 1973 novel, The Castle of Crossed Destinies, inspired by arrangements of tarot cards, and leads through to more recent artistic interpretations and uses of tarot, including Suzanne Treister’s Hexen series that map all today’s ecological, scientific, and political issues into richly presented tarot works. Themes include the data industrial complex, social media, industrial ecology, quantum computing, environmental activisim and the history of the web. The final room is an enclosed Tarotkammer, presenting Treister’s pack alongside others by contemporary practitioners, including a set from John Walter combining tarot with queer sexual history, and Plastique Fantastique’s set drawing from memes and modern day tech-infused ecologies.

figs.xxii,xxiii

The Warburg has long been a place London’s artist’s have been drawn to for research into unexpected visual and social histories, whether discovering it through Gombrich’s The Story of Art or through specific needs of particular, niche research. Katy Hessel, author of recent book The History of Art Without Men, describes the Warburg as “like no other, with one of the most imaginative, inventive and brilliant libraries in the world,” while Maria Balshaw, the Director of Tate, has described it as “London’s best kept secret.”

Now, it is less of a secret, with Charles Holden’s architecture respectfully refurbished and added to by Haworth Tompkins and more open to the public than ever before. With a cultural programme – which will include future exhibitions on Art & the Book and a major new film commission from founding-member of the Black Audio Film Collective, Edward George – it is also a place where that research seeps into the city a bit more, revealing slightly more of the energy of London concealed behind polite brick façades.

figs.xxiv,xxv

The Warburg Institute was founded in Hamburg by the

pioneering scholar Aby Warburg (1866-1929), its scholars, books and images rescued

from Nazi Germany and brought to London in 1933. This included the Institute’s

legendary library, with its expansive system connecting the textual and the visual,

the scientific and the spiritual. It joined the University of London in 1944

and is now part of the School of Advanced Study, the UK’s national centre for

the promotion and facilitation of research in the humanities.

The Warburg Institute has served, during a turbulent

century, as a creative crucible for scholars, curators and all those whose work

sits outside traditional academic structures. Its collections, courses and programmes

are devoted to studying the movement of culture across barriers—of time, space

and discipline—with a special emphasis on the afterlife of antiquity. It has

been home to some of the world’s most influential historians: among the books

written by its staff are Frances Yates’s The Art of Memory and Ernst Gombrich’sThe Story of Art. Over the last few years, it has become a partner in

international exhibitions including the reconstruction of Warburg’s Bilderatlas

Mnemosyne at HKW in Berlin and a historic display at the Uffizi in Florence.

Following the Warburg Renaissance project, a major

transformation of The Warburg Institute led by Stirling Prize-winning

architects Haworth Tompkins, the Institute has launched a dynamic programme of

public exhibitions and events in a series of new spaces, including a dramatic

140 seat auditorium and a state-of-the-art centre for special collections and

the Institute’s first gallery.

The expanded programmes will include Fellowships for

practitioners-in-residence and commissions for contemporary artists, writers

and thinkers. It restores the Institute's original emphasis on discovery, display

and debate, and opens the doors of the Institute to new publics and partners.

www.warburg.sas.ac.uk

Haworth

Tompkins are a London-based architects formed in 1991 by Graham Haworth and

Steve Tompkins. Their projects have won over 180 major design awards, including

the RIBA Stirling Prize in 2014, and they were named AJ100 Practice of the Year

in both 2020 and 2022. As a practice and as individuals a sense of social

purpose is a key driver for their work, and are both a B Corp and an Employee

Ownership Trust. They have over 30 years’ experience of collaborating with

socially driven organisations and clients who share the belief in the responsibility

to create spaces for people and communities and not for the profit of the few. Members of the team sit on the board for

Blueprint For All (formerly Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust), and mentor

through the RIBA and the Social Mobility Foundation. They run an established

work experience programme offering experience of practice to school students

interested in a career in architecture and have worked with school groups

through the RIBA Architecture Ambassadors scheme, sponsor Arts Emergency,

Theatres Trust, and Blueprint for All.

www.haworthtompkins.com

Will Jennings

is

a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities,

architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of

Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches

history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of

UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.haworthtompkins.com