Venice Biennale 2025: part 2, the bad

To mark the end of the 2025 Venice Biennale of Architecture we are reproducing our three main articles - the Good, the Bad & the Ugly - covering the event, originally published on the recessed.space Substack. Here we have, the Bad.

The 2025 Venice Biennale of Architecture has just ended, so we are revisiting our articles published on our Substack newsletter from opening week. Yesterday we looked at the Good (00304), with a wide selection of national pavilions and exhibitions across the city.

Today, we look at the opposite of the spectrum, the Bad – focusing on the main exhibition of the Biennale:

The curator of La Biennale Architettura 2025, its 19th edition, was Carlo Ratti. An Italian Engineer and architect with a studio in Turin and teaching positions at both Massachusetts Institute of Technology [MIT] and the Politecnico di Milano, Ratti is a devout technophile with a practice fusing architectural and urban issues with digital technologies. His curation of the main show, packed into the industrial sheds of Venice’s Arsenale, doesn’t so much speak to that techno-utopian future, but shouts it at you, screaming “ROBOTS, DATA, AI, TECH” in your face. If you like robots and biophilic structures made of 3D printed biomatter, then Ratti has just the biennale for you!

While there are some lovely and genuinely interesting moments in the show, there is simply way too much – it’s not that it’s (just) badly curated, it’s quite simply over-curated. It all starts, however, in a fairly minimal, sensorial way, that while is a clunky metaphor that hits with the subtlety of drone crashing to the ground does at least offer a space of pause before the digital onslaught. Through a black curtain from the entrance lobby, the visitor enters a hot, dark, humid room and finds themselves inside an air conditioning system. It is designed to remind us (as if we had forgotten) that the world is heating up, we should feel uncomfortable, and that old tech is bad. Then we pass through another black curtain into the comparative cool to be told that all new tech is great.

![]()

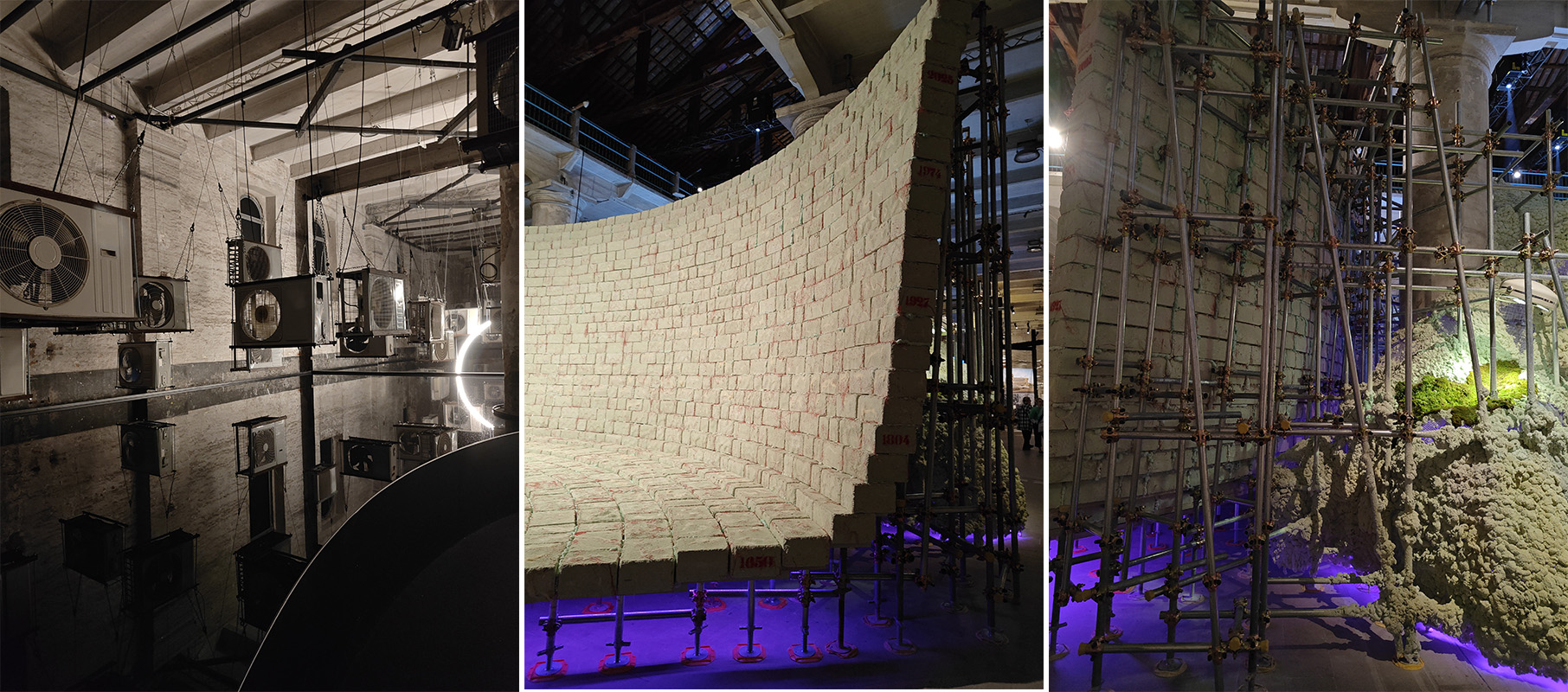

There are some impressive and aesthetically interesting set pieces that string through the curation, starting with a sharply-rising hill that has a topology mapping global population increase, formed of brick like components. The other side the height drops dramatically, reflecting an expected future and rapid population decrease, but that side of the mound is made of what looks like bacteria and microbes – we need to think differently with how we build, get it? If it wasn’t obvious enough, you will be reminded many more times that in Ratti’s future, 3D printing of microbial matter will be the only way to build. Sure, most of us in landscape architecture and architecture agree it is on the rise and will be important, but this Biennale is overgrown with the stuff – it’s hard to turn a head or corner without being confronted by yet another Gaudi/Geiger/Heatherwick-esque wobbly tower made with a magical new/ancient material grown in some university lab then printed by a robotic arm.

Some stones have had holes cut in them and theatrical smoke pumped through to kind of tell us they even rocks are slow lives. Trees have been added to with some ugly specially-shaped 3D printed elements by Kengo Kuma to help use them as structural components. A wide natural fibre net structure stretches from the ceiling and columns, with light shooting through it to show the lines of stress and exertion, though it’s never really explained in the accompanying verbose wordage why this is useful of interesting.

![]()

There are some actual interesting moments that punch through, however. A sweet, small structure made from waste banana fibre speaks to how the world’s most consumed fruit, now largely a monoculture, could provide analogue building materials for a sustainable architectural ecology. From Zicheng Xu and Kevin Mastro (yes, from Cambridge, Massachusetts) it is one of the few presentations that is not attached to a screen, has a moving robot-arm, or tells us we should fuse digital into nature and create a technatural future.

The problem is that we have been promised versions of this Technotopia each generation since the first mechanical loom. It is at the root of Karl Marx, Walter Benjamin, and other theoretical writers (including more recently Shannon Mattern’s The City is not a Computer) usually central to modern architectural writing and thinking, but which are conspicuously absent here. The luddites are often misunderstood, they were not against changes in technology but, like the Chartists in 1840s Britain, wanted financial, social, and political compensation for the impact it would make upon labour, community, and humanity.

There is not much room for such conversations in Ratti’s world, save a moment from US activist group Architectural Lobby who have a poster shouting “thank you for your free labour” in eyeshot of the starchitects and techbros who will rock the Biennale stage – a message perhaps aimed at them, but also perhaps targeting: the Biennale with its famously low payments that means participants not from wealthy universities or foundations must crowdfund to participate; Ratti with his useful interns; or perhaps any member of the visiting public from the cultural sector who know their work is already being pillaged and abused by enormous AI firms in the creation of the conditions and machines to make us all unemployed and unemployable.

![]()

Another interesting presentation, and one which does utilise technology, made by a team based in the US but collaborating with the Greek Council for Refugees amongst others, shows us the architectures and structures of computer systems and surveillance, borders, and bodily control. It reminds us that in the 1980s we put hope into new computer systems to show us solutions to growing global complexities and dangers, but how now those very processes and systems have created the risks, danger, and political authoritarianism of today.

A series of models show us in scale detail the border sites, drones, fingerprint scanners, infrared cameras, asylum centres, and biometric data collection sites that cover Greece. It is a haunting reminder that the technofuture each generation promises is usually then co-opted and used against the very people it said it would help and save. Ratti would do well to find this presentation amongst the sprawl he has curated, then spend some time considering it.

Sometimes nature makes an appearance where it isn’t a tool for mankind to keep developing, like with the bio-structures, but as something to eat or, gasp, simply keep because, you know, trees and plants are nice and good… It is, however, often trapped in plastic – there are retrofuturistic biodomes, and a Space Garden by Heatherwick Studio that looks like a landmine twisted with his signature treatment. But, for the most part, this is a building- not landscape-architecture presentation and only brings landscape or nature into the conversation when nature can be utilised to support a prospering society – there is not much space for how society might change its ways to help a prospering nature.

![]()

Ratti is proud to state that this is the first biennale curation that began with a global open call, rather than hand-selection of participants. Rumours emanating from inside the process, however, suggest that while there were 1,000 applicants to that callout, the majority were white men from the global north, and then of variable quality. It is thought that this may have led to a slight panic from the curatorial team who then had to go and find new participants, though with Ratti’s frame of reference being the narrow silos of MIT, Politecnico, and Techbro acolytes, it possibly didn’t widen the exhibiting gene pool hugely. At points, you might even be mistaken for thinking that the event is titled La Biennale MIT 2025.

Each of the hundreds of projects that were selected (including countless panel displays of text and image which really could exist as a book or website) show information of where each artist/designer/architect is from and where they practice. It would be a thankless task to read every single text, but there were clearly not many participants from the Global South, and especially few from the Middle East regions. This seems to be a huge blindspot, especially at a time when inequality is expanding on pre-existing colonial models, when the US coasts are not only designing our tech future but also, seemingly, our political one, and when the extractive industries required for Ratti’s technotopia are violent, damaging, and almost always impact the Global South and perpetuate existing inequalities.

As well as the small-type info on the project and makers, each of Ratti’s information panels contain a few dense paragraphs of descriptive text. If you were to read all of these it would take a lifetime, so helpfully Ratti has got his interns to feed it all into Chat GPT to create short “AI Summaries” underneath. These are certainly quicker to read and are usually more clear, concise, and communicative than the heavy writing above. We all know the risks of Chat GPT and AI to the creative industries, but perhaps here we learn it might have a saving grace – to help improve famously dense, jargon-filled, unintelligible writing that too many architects still subscribe to.

![]()

Outside of Biennale, the news constantly reminds us that it isn’t only the creative world that robots and AI will help/destroy, but all human crafts, skills, and knowledge. Here, we are reminded of it further through all the various robots Ratti has scattered across the venue – if last year’s art Biennale was titled “Foreigners Everywhere” surely somebody proposed that this years could be titled “Robots Everywhere”?

There is a robot we speak to in any language and it will respond, awkwardly waving its limbs as if it’s an Italian kindergarten kid learning hand gestures. There is a robot that eventually bangs a steel drum after a human hits one nearby – very, very useful. There is a robot dangling from the ceiling within a net structure as if caught by some future-tech fishing industry trawling the bed of a space-sea for nutrition from redundant or machines. Robots everywhere.

There are more. There is a robot arm that seems to be trying to help traditional craftspeople who are carving a decorative timber beam for Bjarke Ingels by brushing the dust away – though it seems to be getting in the way more than helping, and one wonders if one of the starchitects couldn’t have just donated an unpaid intern for a few months to get on-the-job experience and exposure. There’s one of those robot dogs that everybody shared on the internet when military manufacturers strapped AI-guns onto their backs, but here it has a weird waving arm not a gun – it turns out it is a construction worker lunardog, designed to build all the data farms on the moon that citizens technobros and authoritarian leaders will demand. Robots everywhere.

![]()

There is so much disingenuously left out of Ratti’s technotopic vision that should be part of the conversation, present as a huge blind spot. As well as the lack of real critique of extractive requirements of tech, the inequality it perpetuates, and the lack of diversity amongst the display, there is also no space to discuss the technology-military-industrial complex, the relationship to culture and computer games, how technology can be used by citizens to oppose techno-fascist states, the relationship of tech to increasingly right wing regimes, and much more. The curation strictly follows Ratti’s world view, and that is not the role of a curator, or the sign of good curation.

In this packed curation, there is very little room left for the human. Both literally, in that it is physically hard to navigate the Arsenale halls due to the sheer density of content and stuff, there is no room for the human to move amongst this technology. But, also, figuratively, Ratti’s future leaves little space to imagine humans (especially these not from a university lab) might develop human/community/nature solutions and not rely on a future where we are subservient to a robot-led humanity and nature.

![]()

There is also little space to consider who controls the robots, data, and systems that it expects will take over all our decisions and roles – though judging by the names and institutions throughout the show, the controllers will predominantly be a few wealthy institutions and well-connected men from a few small pockets of the planet’s north side.

The few moments of opposition, protest, or criticality that are present – such as Architecture Lobby and also a sculpture from a team led by Alejandro Aravana’s ELEMENTAL about housing – stating that the housing market “places elites at the top of the pyramid who abuse the system for private benefit” – seem like they sneaked in accidentally or were put in place just to give some minimal sense of awareness and nuance from the curating team. Indeed, arguably Ratti has filled this Biennale with precisely those elites Aravana refers to – or, at least, the eclebrated architects and designers who flirt with those elites in order to climb to the pyramid’s peak.

Today, we look at the opposite of the spectrum, the Bad – focusing on the main exhibition of the Biennale:

The curator of La Biennale Architettura 2025, its 19th edition, was Carlo Ratti. An Italian Engineer and architect with a studio in Turin and teaching positions at both Massachusetts Institute of Technology [MIT] and the Politecnico di Milano, Ratti is a devout technophile with a practice fusing architectural and urban issues with digital technologies. His curation of the main show, packed into the industrial sheds of Venice’s Arsenale, doesn’t so much speak to that techno-utopian future, but shouts it at you, screaming “ROBOTS, DATA, AI, TECH” in your face. If you like robots and biophilic structures made of 3D printed biomatter, then Ratti has just the biennale for you!

While there are some lovely and genuinely interesting moments in the show, there is simply way too much – it’s not that it’s (just) badly curated, it’s quite simply over-curated. It all starts, however, in a fairly minimal, sensorial way, that while is a clunky metaphor that hits with the subtlety of drone crashing to the ground does at least offer a space of pause before the digital onslaught. Through a black curtain from the entrance lobby, the visitor enters a hot, dark, humid room and finds themselves inside an air conditioning system. It is designed to remind us (as if we had forgotten) that the world is heating up, we should feel uncomfortable, and that old tech is bad. Then we pass through another black curtain into the comparative cool to be told that all new tech is great.

There are some impressive and aesthetically interesting set pieces that string through the curation, starting with a sharply-rising hill that has a topology mapping global population increase, formed of brick like components. The other side the height drops dramatically, reflecting an expected future and rapid population decrease, but that side of the mound is made of what looks like bacteria and microbes – we need to think differently with how we build, get it? If it wasn’t obvious enough, you will be reminded many more times that in Ratti’s future, 3D printing of microbial matter will be the only way to build. Sure, most of us in landscape architecture and architecture agree it is on the rise and will be important, but this Biennale is overgrown with the stuff – it’s hard to turn a head or corner without being confronted by yet another Gaudi/Geiger/Heatherwick-esque wobbly tower made with a magical new/ancient material grown in some university lab then printed by a robotic arm.

Some stones have had holes cut in them and theatrical smoke pumped through to kind of tell us they even rocks are slow lives. Trees have been added to with some ugly specially-shaped 3D printed elements by Kengo Kuma to help use them as structural components. A wide natural fibre net structure stretches from the ceiling and columns, with light shooting through it to show the lines of stress and exertion, though it’s never really explained in the accompanying verbose wordage why this is useful of interesting.

There are some actual interesting moments that punch through, however. A sweet, small structure made from waste banana fibre speaks to how the world’s most consumed fruit, now largely a monoculture, could provide analogue building materials for a sustainable architectural ecology. From Zicheng Xu and Kevin Mastro (yes, from Cambridge, Massachusetts) it is one of the few presentations that is not attached to a screen, has a moving robot-arm, or tells us we should fuse digital into nature and create a technatural future.

The problem is that we have been promised versions of this Technotopia each generation since the first mechanical loom. It is at the root of Karl Marx, Walter Benjamin, and other theoretical writers (including more recently Shannon Mattern’s The City is not a Computer) usually central to modern architectural writing and thinking, but which are conspicuously absent here. The luddites are often misunderstood, they were not against changes in technology but, like the Chartists in 1840s Britain, wanted financial, social, and political compensation for the impact it would make upon labour, community, and humanity.

There is not much room for such conversations in Ratti’s world, save a moment from US activist group Architectural Lobby who have a poster shouting “thank you for your free labour” in eyeshot of the starchitects and techbros who will rock the Biennale stage – a message perhaps aimed at them, but also perhaps targeting: the Biennale with its famously low payments that means participants not from wealthy universities or foundations must crowdfund to participate; Ratti with his useful interns; or perhaps any member of the visiting public from the cultural sector who know their work is already being pillaged and abused by enormous AI firms in the creation of the conditions and machines to make us all unemployed and unemployable.

Another interesting presentation, and one which does utilise technology, made by a team based in the US but collaborating with the Greek Council for Refugees amongst others, shows us the architectures and structures of computer systems and surveillance, borders, and bodily control. It reminds us that in the 1980s we put hope into new computer systems to show us solutions to growing global complexities and dangers, but how now those very processes and systems have created the risks, danger, and political authoritarianism of today.

A series of models show us in scale detail the border sites, drones, fingerprint scanners, infrared cameras, asylum centres, and biometric data collection sites that cover Greece. It is a haunting reminder that the technofuture each generation promises is usually then co-opted and used against the very people it said it would help and save. Ratti would do well to find this presentation amongst the sprawl he has curated, then spend some time considering it.

Sometimes nature makes an appearance where it isn’t a tool for mankind to keep developing, like with the bio-structures, but as something to eat or, gasp, simply keep because, you know, trees and plants are nice and good… It is, however, often trapped in plastic – there are retrofuturistic biodomes, and a Space Garden by Heatherwick Studio that looks like a landmine twisted with his signature treatment. But, for the most part, this is a building- not landscape-architecture presentation and only brings landscape or nature into the conversation when nature can be utilised to support a prospering society – there is not much space for how society might change its ways to help a prospering nature.

Ratti is proud to state that this is the first biennale curation that began with a global open call, rather than hand-selection of participants. Rumours emanating from inside the process, however, suggest that while there were 1,000 applicants to that callout, the majority were white men from the global north, and then of variable quality. It is thought that this may have led to a slight panic from the curatorial team who then had to go and find new participants, though with Ratti’s frame of reference being the narrow silos of MIT, Politecnico, and Techbro acolytes, it possibly didn’t widen the exhibiting gene pool hugely. At points, you might even be mistaken for thinking that the event is titled La Biennale MIT 2025.

Each of the hundreds of projects that were selected (including countless panel displays of text and image which really could exist as a book or website) show information of where each artist/designer/architect is from and where they practice. It would be a thankless task to read every single text, but there were clearly not many participants from the Global South, and especially few from the Middle East regions. This seems to be a huge blindspot, especially at a time when inequality is expanding on pre-existing colonial models, when the US coasts are not only designing our tech future but also, seemingly, our political one, and when the extractive industries required for Ratti’s technotopia are violent, damaging, and almost always impact the Global South and perpetuate existing inequalities.

As well as the small-type info on the project and makers, each of Ratti’s information panels contain a few dense paragraphs of descriptive text. If you were to read all of these it would take a lifetime, so helpfully Ratti has got his interns to feed it all into Chat GPT to create short “AI Summaries” underneath. These are certainly quicker to read and are usually more clear, concise, and communicative than the heavy writing above. We all know the risks of Chat GPT and AI to the creative industries, but perhaps here we learn it might have a saving grace – to help improve famously dense, jargon-filled, unintelligible writing that too many architects still subscribe to.

Outside of Biennale, the news constantly reminds us that it isn’t only the creative world that robots and AI will help/destroy, but all human crafts, skills, and knowledge. Here, we are reminded of it further through all the various robots Ratti has scattered across the venue – if last year’s art Biennale was titled “Foreigners Everywhere” surely somebody proposed that this years could be titled “Robots Everywhere”?

There is a robot we speak to in any language and it will respond, awkwardly waving its limbs as if it’s an Italian kindergarten kid learning hand gestures. There is a robot that eventually bangs a steel drum after a human hits one nearby – very, very useful. There is a robot dangling from the ceiling within a net structure as if caught by some future-tech fishing industry trawling the bed of a space-sea for nutrition from redundant or machines. Robots everywhere.

There are more. There is a robot arm that seems to be trying to help traditional craftspeople who are carving a decorative timber beam for Bjarke Ingels by brushing the dust away – though it seems to be getting in the way more than helping, and one wonders if one of the starchitects couldn’t have just donated an unpaid intern for a few months to get on-the-job experience and exposure. There’s one of those robot dogs that everybody shared on the internet when military manufacturers strapped AI-guns onto their backs, but here it has a weird waving arm not a gun – it turns out it is a construction worker lunardog, designed to build all the data farms on the moon that citizens technobros and authoritarian leaders will demand. Robots everywhere.

There is so much disingenuously left out of Ratti’s technotopic vision that should be part of the conversation, present as a huge blind spot. As well as the lack of real critique of extractive requirements of tech, the inequality it perpetuates, and the lack of diversity amongst the display, there is also no space to discuss the technology-military-industrial complex, the relationship to culture and computer games, how technology can be used by citizens to oppose techno-fascist states, the relationship of tech to increasingly right wing regimes, and much more. The curation strictly follows Ratti’s world view, and that is not the role of a curator, or the sign of good curation.

In this packed curation, there is very little room left for the human. Both literally, in that it is physically hard to navigate the Arsenale halls due to the sheer density of content and stuff, there is no room for the human to move amongst this technology. But, also, figuratively, Ratti’s future leaves little space to imagine humans (especially these not from a university lab) might develop human/community/nature solutions and not rely on a future where we are subservient to a robot-led humanity and nature.

There is also little space to consider who controls the robots, data, and systems that it expects will take over all our decisions and roles – though judging by the names and institutions throughout the show, the controllers will predominantly be a few wealthy institutions and well-connected men from a few small pockets of the planet’s north side.

The few moments of opposition, protest, or criticality that are present – such as Architecture Lobby and also a sculpture from a team led by Alejandro Aravana’s ELEMENTAL about housing – stating that the housing market “places elites at the top of the pyramid who abuse the system for private benefit” – seem like they sneaked in accidentally or were put in place just to give some minimal sense of awareness and nuance from the curating team. Indeed, arguably Ratti has filled this Biennale with precisely those elites Aravana refers to – or, at least, the eclebrated architects and designers who flirt with those elites in order to climb to the pyramid’s peak.