Venice Biennale 2025: part 1, the good

To mark the end of the 2025 Venice Biennale of Architecture we are reproducing our three main articles - the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly - covering the event, originally published on the recessed.space Substack. To start, here is the Good.

Venice Biennale is a strange beast. At once so large that it’s hard to find a single narrative or thread between the vast array of pavilions and collateral shows across the Giardini and Arsenale sites as well as the wider city, but within the work of thousands of architects and artists a unique experience for surprise, pleasure, creativity, and idea.

It’s also one so large that we had to split our response from the Biennale’s opening week into three parts, focussing on the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. These were originally published on the recessed.space newsletter (here) and to mark the closing of this year’s edition we are reproducing the coverage here on the main website.

![]()

Landscape architect Bas Smets and neurobiologist Stefano Mancuso collaborated for Belgium, filling their building with trees and plants for the next six months, creating a new microclimate and throughout recording and documenting the lives that the plants lead with technology and data points across the rooms and nature. Their theory is that the plants will comprehend and transform the room to suit their needs through an inherent intelligence and so the 200 plants in the space are integrated into a technological feedback loop in which data recorded from their behaviours will directly change the ventilation, lighting, and irrigation of the space in a conversation between nature and technology.

Canada have also created an experiment, with Picoplanktonics, a project from Living Room Collective that has created robot-printed biofabricated structures that will be studied until Biennale ends in November. The structures are embedded with cyanobacteria, one of the earth’s earliest life forms, which slowly harden during a process of absorbing and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide and emitting oxygen. Some strucures are contained within atmospheric-controlled vitrines, others are simply left outside to observe their ageing process, while – most dramatically – two are HR Geiger-esque towers sitting in a pool of saline solution, biophilic in form, an aesthetic counter to the modernist form of the Pavilion, while speaking to the more traditional nature growing around the building.

Montenegro presented a pavilion that was also alive. Here, the team of Miljana Zeković in collaboration with Ivan Šuković, Dejan Todorović, and Emir Šehanović have looked to traditional Montenegrin dry stone walls to examine then support microorganisms discovered. In what they call a “quiet revolution”, they state that the bacteria constructs advanced spatial configurations that could be scaled up, and they produce in response to the environmental conditions they encounter. This is also an experiment in process, without a real knowledge of any potential architectural or engineering outcome, the conditions for growth have been set up in a dark room full of vitrines containing the various bacteria from regions of Montenegro.

![]()

One of the most Instagrammable pavilions was the Netherlands, who went down the playful, colourful, and queer route with a yellow and purple sportsbar as a space of celebration and experimentation. In a Biennale format in which nations compete to win the much-lauded Golden Lion award, the Netherlands pushed for a space where there was no competition, and through sport tested what collaboration and allyship might look like. Sure, it pushes at the edges of architecture and many cishet architects of a certain generation might be confused or angered, but that may not be a bad thing… New situationist-inspired sports – including five-team football and wobbly table football – are presented alongside research of and communication with queers who play sports, own sports bars, manage gyms, and more to remind us of joy and solidarity in a world that, like sport, becomes binary, competitive, and angry.

GRACE architects from Milan have been bravely minimalist with their installation for Uzbekistan. The presentation builds upon the firm’s long work for the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation in cataloguing and recognising Tashkent Modernism, now under consideration for UNESCO recognition. One of the ten architectural examples within the bid is the Sun Heliocomplex built in 1987 one hour outside of Tashkent. In the mountains, chosen from across the Soviet Union because of its safety from earthquakes and amount of sunshine, sits a remarkable array of mirrors that reflect the sun towards a huge concave mirror that directs the rays to a central scientific furnace. It can reach temperatures of 3000° Celsius very quickly, and is used to develop and test new material technologies. The Biennale presentation carefully refined, and instead of packing the room with information, models, it presents scale models of an array mirror and architectural façade element alongside fragments and objects. You can visit our story 00279 to find out more about this project and our visit to the Helioplex building.

Another extremely well curated pavilion by a team who understood that an exhibition is a different form of communication to a book or a building, was the wonderful, cartoonish, playful offer from Poland. Titled On Building a Sense of Security in Architecture, it presented the many ways designers, authorities, and the public imbue security in buildings – from the regulatory to the superstitious. A box of soil had some eggshells tossed in as there’s a belief that to add them to foundations will ensure success for future occupants. The gallery’s fire alarm had a huge red circle extenuating its presence and the fuse panel was exposed and framed like an art object. Security fences were made into a totem, a security camera had its frame of vision shown through a fluffy cast on the wall, and the fire escape door was supplanted by not one but 75 fire escape signs from across the world. It was genuinely humorous, but with a simple architectural vantage at heart, and very well paced as an exhibition.

![]()

Some of the more successful pavilions were those that, as mentioned, understood the format of exhibition as a specific form of communication. Slovenia did it, with a simple one liner but a welcome reminder in a Biennale that relies on a lot of unpaid or underpaid labour. Called Master Builders, a series of large, somewhat-PoMo sculptural totems made from architectural fabrication and masonry work had no function at first reading. But near each one was an information board breaking it down into weight, dimensions, total hours of work to make, then a breakdown of which workers those were. For one we learn that a metalworker (7 hours), mason (10 hours), roofer (3 hours), drywall installer (18h), carpenter (2 hours), electrical installer (2 hours), then gallery installers (3 hours) contributed to the single work. In art and architecture workls where final objects appear to miraculously appear, pristine in a gallery, it’s a healthy reminder or the ecosystem and skills that are behind everything made.

The Nordic pavilion may be famous for its Sverre Fehn-designed architecture, but it’s becoming the must-see for its exhibitions now, with a series of art and architecture biennales with singular, richly presented, and political ideas. The immaculate space has been disturbed and upturned with post-apocalyptic scenography. It’s by a team led by performance artist Tea Ala-Ruona and explores modernist landscapes through the trans body, the various works – including a car punctured by concrete columns – offering themselves up as the stageset for performances set to speculative scores.

Serbia offered up what we think should have been Golden Lion winner, though can see that for some architects present it again fell too far on the art/conceptual side – “but where are the models, plans, and manifestos!?” you could hear visitors think… A minimal installation that it turns out would only become more minimal, the room is dominated by an undulating slung ceiling formed of wool that has been knitted by both hand and machine. Several loose ends are connected to wall-mounted spools that slowly rotate, gently undoing the work, returning the wool to a skein. Poetic, subtle, silent, but also speaking to labour, collaboration, and the act of undoing.

![]()

Away from the two main Biennale sites of the Giardini and Arsenale, there is plenty happening across the city. Sure, not as much as the overly-crammed Art Biennale, but enough to pack a week on the island needing about 25,000 steps a day. The Fondazione Querini Stampalia is always on the list for any architecture lover visiting Venice, housed in a 16th century palazzo wonderfully renovated and expanded by Carlo Scarpa between 1959 and 1963, including his celebrated garden. This work includes a suite of gallery spaces, currently showing conceptual photography by artist John Baldessari. It’s a rich, and very well-presented exhibition, conceptual and clever, but never inaccessible or enjoyable to all. Throughout, the artist’s sense of play with space and time is present, through positioning, overlaying, cutout, and script-like progression through images.

www.querinistampalia.org

The Arsenale Institute for Political Representation studies culture, philosophy, and politics through pictorial research, with special focus on the early 20th century avant-garde. It presents a range of unexpected, critical, and well-presented shows, and currently presents a display on the history of the barricade. Paris recurs throughout as a city that loves a barricade – from the police and protest sides – but it reaches further, even into Venetian history. There is somewhat a lack of visitor explanation and context for the rich artefacts on display (other than an overly-wordy text panel adhered to the external wall) but even without the guided walkthrough we experienced, the wealth of artefacts on display – from late Renaissance books to boardgames of the late-20th century – are rich throughout.

www.arsenale.com

The Making of the Body in Renaissance Venice: Leonardo, Michelangelo, Dürer, Giorgione is a little misleading as a title. These four incredible artists do appear throughout the rooms of Gallerie dell'Accademia, but this deep and rich exploration of the body in art is far more than these men in the subtitle. It’s a presentation that veers from scientific to erotic, realistic to romantic, but one rich and fascinating at every turn. Using our current preoccupation with the body (and the self) as a hook to explore the past, we start by visiting Antonio Rizzo’s handsome Adam, the first monumental nude in Venice, dating from around 1472. But we also witness a carved ivory female anatomical manikin, many da Vinci drawings including of the cardiovascular system, cross-sections of the skull, and the seminal Vitruvian Man, wonderous Dürer works and even 16th century prosthetic limbs, drawings for a steampunk mechanical hand, and even a room of erotic pornography that propelled the early printing industry.

www.gallerieaccademia.it

![]()

One of the most unexpected, and perhaps most un-Venetian, exhibitions this year was the newly-opened Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation. At both Biennales we may be used to the rarefied modern art object being artfully placed within an historic palazzo, but here – in a curation by Hans Ulrich Obrist and artist Tolia Astakhishvilli – a building has been stripped back, revealed, rearranged, and operated on as if by a brutal backstreet surgeon, revealing its innards as a space of uncanny distortion, display, and play. To Love and Devour features works from eight other artists in the eclectic arrangement, it’s a site-specificity rarely experienced in this neat city, and all the more enjoyable for it. The first exhibition by the Foundation, and created in situ by Astakhishvili over months in the building, there’s something of a 21st century Gordon Matta Clark in the approach, but instead of trying to carve a clarity and geometric order within chaos, here there is only new complexity and disorder folded into what is found – very much speaking, perhaps, to our world today. Have a look at recessed.space article 00294 for deeper coverage of the show.

www.nf.foundation

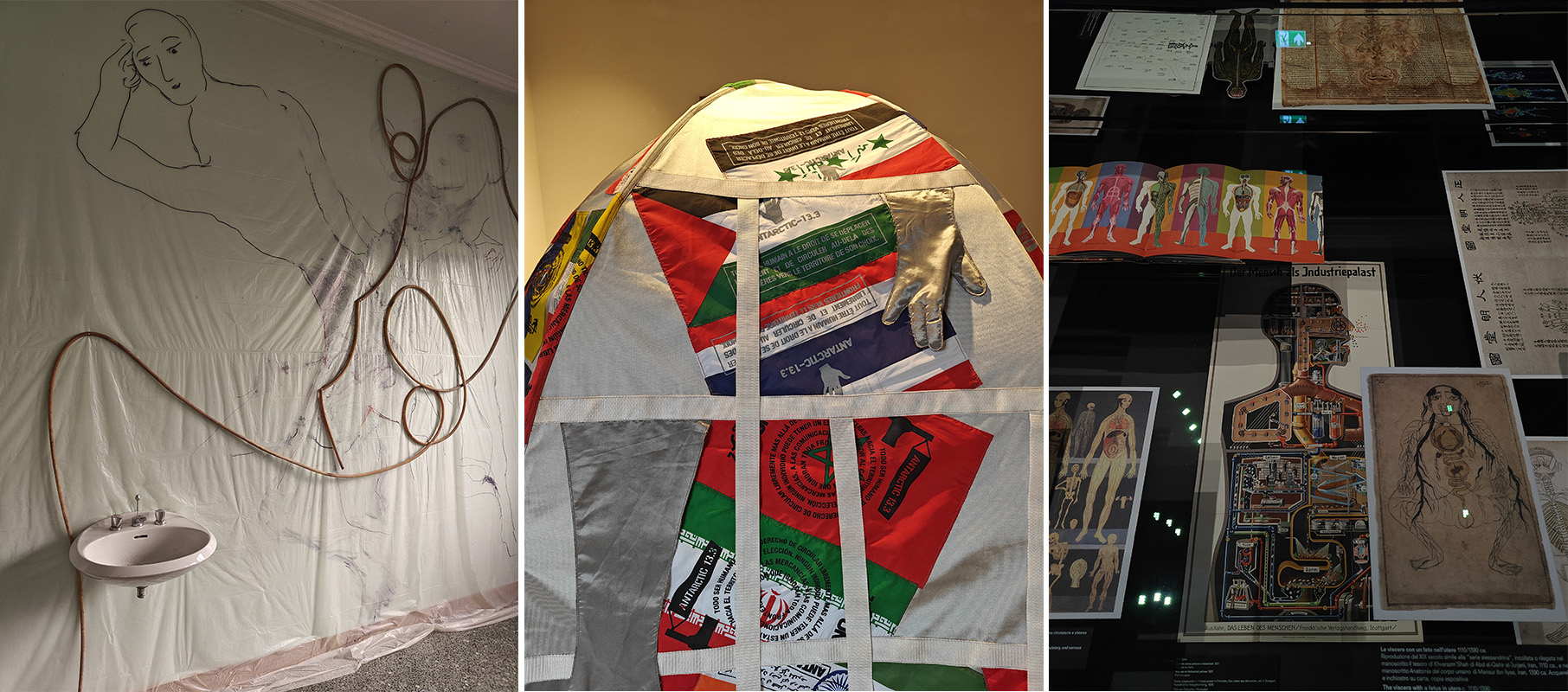

The Potential Architecture of Lucy and Jorge Orta is shown at the SPARC* Venice Art Academy – but only as an exhibition slightly overlapping with Biennale, so you’ll need to be quick to see it before it ends on 16 May. If you do get there, you’re in for a treat with several of English artist Lucy Orta’s celebrated architectural-clothing drawings that speak to the body, migration, climate, and survival. Central to the presentation is one of their Antarctica Dome Dwelling tents, a tent for an apolitical, unowned, unspoilt place made of flags from those at risk, attacked, who are now refugees, or are suffering. Shelter is further explored in a series of drawings, models, and glass-blown sculptures that speak to the idea of a growing cell, expanding upon existing buildings to create spaces of security and living.

www.veniceartfactory.org

At Fondazione Prada immaculate vitrines present a rich history of diagrams, spanning centuries, nations, and meaning. Not only the vitrines, but the project is by Rem Koolhaas-founded architects and researchers AMO/OMA and it seeks to explore the history of visual communication, an approach used by the firm in much of their work and drawing. Within the show there are countless rich documents – though, frustratingly many of them are museum reproductions rather than original documents. That said, at moments the presentation sings (especially with a layered-glass vitrine of body diagrams) and offers a valuable resource to visual communicators of all fields. It is not a fun show, though it would be a hard push to make a curation of data playful, but it is rich and deep.

www.fondazioneprada.org

![]()

Carlo Scarpa left more marks in Venice than his work at Querini Stampalia. The Museu Correr, overlooking Saint Mark’s Square, is rich and ornate throughout, but the sequence of spaces redesigned by Carlo Scarpa between 1953 and 1960 are sure to excite many visiting architects. His paired back approach with immaculate and signature detailing is celebrated in a small but interesting exhibition of Scarpa’s original display cases and presentation easels, which may sound unusual – has anybody ever heard of an exhibition of empty vitrines before? – but is a welcome celebration that helps the visitor then read all connecting spaces and displays with a new fluency.

www.correr.visitmuve.it

Another of Venezia’s newer institutions, the Scuola Piccola Zattere is a non-profit space for education and exhibition, its name taken from a uniquely Venetian model of civic organisation that was widespread and inclusive. With exhibitions rooted in the research of invited artists, the current exhibition is by French artist Gaëlle Choisne as part of ongoing research since 2018, and is a rich, playful mingling of the artist’s Haitian heritage – including 18 Haitian artists from a private collection in display alongside Choisne’s own mixed-media works that speak to coiexitence, collaboration, and hospitality.

www.scuolapiccolazattere.com

SMAC – short for San Marco Art Centre – is another new institution, this one occupying the Procuratie Vechie, recently refurbished by David Chipperfield. Here, two exhibitions programmed to coincide with the Architecture Biennale fill the series of terrazzo-floored rooms. On one side, a richly curated show of the modernist architecture of Harry Seidler takes the visitor through the architect’s life, from his 1938 escape from Vienna to Britain, then 1940 refugee internment and deportation to Canada as an ‘enemy alien’ by Winston Churchill, through his later career as one of the most influential modernist architects in Australia. The other wing is an exhibition focussed on the work of South Korean landscape architect Jung Youngsun. It’s informative, if tightly focused on the designer through projects and not wider beliefs and experiences, and as such super-reliant upon drawings and photographs as a mode of display, but any exhibition dedicated to any landscape architect is welcome, especially one so important to recent developments in the sector.

www.smac.org & www.smac.org

![]()

We will finish off our roundup of the good from Biennale with three more national pavilions from the Giardini and Arsenale, though ones that push against the grain in this year’s approach. As we will discuss in part two, the Bad of Biennale, much of the exhibition was crowded, intense, noisy, and overly complicated, crammed into small spaces. And so it is interesting that three pavilions stood out by carving moments of calm and relaxation amongst the noise.

Ireland presented Assembly, a simple but meticulously crafted circular chamber designed for local-scale citizens assemblies, where strangers who may otherwise disagree come together to resolve a political issue. It is designed to support such processes as a collaboration between architects, craftspeople, musicians, and writers, and while here is presented as a sculptural form to sit, dwell, and listen in, is easily dismountable and theoretically could travel Ireland offering popup spaces of communication.

In a Biennale dominated by looking, with sight the dominant sense required to navigate the cacophony of stuff, Luxembourg’s deep focus on listening was welcome. A soundscape formed of field recordings across diverse environments critically examined Luxembourgish landscapes, with visitors invited to lay back and let the immersive soundwork float through them. It uses the concept of Ecotone, a transitional space between two ecosystems, to take the listener through the score and find a path through disconnections and co-existences in the presented environments.

Finally, the winner of this year’s Golden Lion for best pavilion similarly created a space that invited slowness, dwelling, and comfort. Bahrain’s Heatwave presented a modular system combining traditional Gulf cooling approaches with contemporary material and environmental research. As an inhabitable space, visitors could move around to feel how architecture creates microclimates through space, material, and form, with passive environmental strategies allowing moments of welcome cooling. It is presented as an experimental space rather than solution, with a mock-up of a geothermal cooling system replicated in the space, cooling the external warm air through underground pipes before releasing it through ceiling orifices. The success of the space couldn’t only be seen through the Golden Lion award, but through the number of people choosing to stop, pause, and remain in the space when the wider Biennale wanted them to speed up and devour the culture on show.

It’s also one so large that we had to split our response from the Biennale’s opening week into three parts, focussing on the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. These were originally published on the recessed.space newsletter (here) and to mark the closing of this year’s edition we are reproducing the coverage here on the main website.

Belgium, Canada, Montenegro

Landscape architect Bas Smets and neurobiologist Stefano Mancuso collaborated for Belgium, filling their building with trees and plants for the next six months, creating a new microclimate and throughout recording and documenting the lives that the plants lead with technology and data points across the rooms and nature. Their theory is that the plants will comprehend and transform the room to suit their needs through an inherent intelligence and so the 200 plants in the space are integrated into a technological feedback loop in which data recorded from their behaviours will directly change the ventilation, lighting, and irrigation of the space in a conversation between nature and technology.

Canada have also created an experiment, with Picoplanktonics, a project from Living Room Collective that has created robot-printed biofabricated structures that will be studied until Biennale ends in November. The structures are embedded with cyanobacteria, one of the earth’s earliest life forms, which slowly harden during a process of absorbing and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide and emitting oxygen. Some strucures are contained within atmospheric-controlled vitrines, others are simply left outside to observe their ageing process, while – most dramatically – two are HR Geiger-esque towers sitting in a pool of saline solution, biophilic in form, an aesthetic counter to the modernist form of the Pavilion, while speaking to the more traditional nature growing around the building.

Montenegro presented a pavilion that was also alive. Here, the team of Miljana Zeković in collaboration with Ivan Šuković, Dejan Todorović, and Emir Šehanović have looked to traditional Montenegrin dry stone walls to examine then support microorganisms discovered. In what they call a “quiet revolution”, they state that the bacteria constructs advanced spatial configurations that could be scaled up, and they produce in response to the environmental conditions they encounter. This is also an experiment in process, without a real knowledge of any potential architectural or engineering outcome, the conditions for growth have been set up in a dark room full of vitrines containing the various bacteria from regions of Montenegro.

Netherlands, Uzbekistan, Poland

One of the most Instagrammable pavilions was the Netherlands, who went down the playful, colourful, and queer route with a yellow and purple sportsbar as a space of celebration and experimentation. In a Biennale format in which nations compete to win the much-lauded Golden Lion award, the Netherlands pushed for a space where there was no competition, and through sport tested what collaboration and allyship might look like. Sure, it pushes at the edges of architecture and many cishet architects of a certain generation might be confused or angered, but that may not be a bad thing… New situationist-inspired sports – including five-team football and wobbly table football – are presented alongside research of and communication with queers who play sports, own sports bars, manage gyms, and more to remind us of joy and solidarity in a world that, like sport, becomes binary, competitive, and angry.

GRACE architects from Milan have been bravely minimalist with their installation for Uzbekistan. The presentation builds upon the firm’s long work for the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation in cataloguing and recognising Tashkent Modernism, now under consideration for UNESCO recognition. One of the ten architectural examples within the bid is the Sun Heliocomplex built in 1987 one hour outside of Tashkent. In the mountains, chosen from across the Soviet Union because of its safety from earthquakes and amount of sunshine, sits a remarkable array of mirrors that reflect the sun towards a huge concave mirror that directs the rays to a central scientific furnace. It can reach temperatures of 3000° Celsius very quickly, and is used to develop and test new material technologies. The Biennale presentation carefully refined, and instead of packing the room with information, models, it presents scale models of an array mirror and architectural façade element alongside fragments and objects. You can visit our story 00279 to find out more about this project and our visit to the Helioplex building.

Another extremely well curated pavilion by a team who understood that an exhibition is a different form of communication to a book or a building, was the wonderful, cartoonish, playful offer from Poland. Titled On Building a Sense of Security in Architecture, it presented the many ways designers, authorities, and the public imbue security in buildings – from the regulatory to the superstitious. A box of soil had some eggshells tossed in as there’s a belief that to add them to foundations will ensure success for future occupants. The gallery’s fire alarm had a huge red circle extenuating its presence and the fuse panel was exposed and framed like an art object. Security fences were made into a totem, a security camera had its frame of vision shown through a fluffy cast on the wall, and the fire escape door was supplanted by not one but 75 fire escape signs from across the world. It was genuinely humorous, but with a simple architectural vantage at heart, and very well paced as an exhibition.

Slovenia, Nordic, Serbia

Some of the more successful pavilions were those that, as mentioned, understood the format of exhibition as a specific form of communication. Slovenia did it, with a simple one liner but a welcome reminder in a Biennale that relies on a lot of unpaid or underpaid labour. Called Master Builders, a series of large, somewhat-PoMo sculptural totems made from architectural fabrication and masonry work had no function at first reading. But near each one was an information board breaking it down into weight, dimensions, total hours of work to make, then a breakdown of which workers those were. For one we learn that a metalworker (7 hours), mason (10 hours), roofer (3 hours), drywall installer (18h), carpenter (2 hours), electrical installer (2 hours), then gallery installers (3 hours) contributed to the single work. In art and architecture workls where final objects appear to miraculously appear, pristine in a gallery, it’s a healthy reminder or the ecosystem and skills that are behind everything made.

The Nordic pavilion may be famous for its Sverre Fehn-designed architecture, but it’s becoming the must-see for its exhibitions now, with a series of art and architecture biennales with singular, richly presented, and political ideas. The immaculate space has been disturbed and upturned with post-apocalyptic scenography. It’s by a team led by performance artist Tea Ala-Ruona and explores modernist landscapes through the trans body, the various works – including a car punctured by concrete columns – offering themselves up as the stageset for performances set to speculative scores.

Serbia offered up what we think should have been Golden Lion winner, though can see that for some architects present it again fell too far on the art/conceptual side – “but where are the models, plans, and manifestos!?” you could hear visitors think… A minimal installation that it turns out would only become more minimal, the room is dominated by an undulating slung ceiling formed of wool that has been knitted by both hand and machine. Several loose ends are connected to wall-mounted spools that slowly rotate, gently undoing the work, returning the wool to a skein. Poetic, subtle, silent, but also speaking to labour, collaboration, and the act of undoing.

Baldessari, Barricades, Bodies

Away from the two main Biennale sites of the Giardini and Arsenale, there is plenty happening across the city. Sure, not as much as the overly-crammed Art Biennale, but enough to pack a week on the island needing about 25,000 steps a day. The Fondazione Querini Stampalia is always on the list for any architecture lover visiting Venice, housed in a 16th century palazzo wonderfully renovated and expanded by Carlo Scarpa between 1959 and 1963, including his celebrated garden. This work includes a suite of gallery spaces, currently showing conceptual photography by artist John Baldessari. It’s a rich, and very well-presented exhibition, conceptual and clever, but never inaccessible or enjoyable to all. Throughout, the artist’s sense of play with space and time is present, through positioning, overlaying, cutout, and script-like progression through images.

www.querinistampalia.org

The Arsenale Institute for Political Representation studies culture, philosophy, and politics through pictorial research, with special focus on the early 20th century avant-garde. It presents a range of unexpected, critical, and well-presented shows, and currently presents a display on the history of the barricade. Paris recurs throughout as a city that loves a barricade – from the police and protest sides – but it reaches further, even into Venetian history. There is somewhat a lack of visitor explanation and context for the rich artefacts on display (other than an overly-wordy text panel adhered to the external wall) but even without the guided walkthrough we experienced, the wealth of artefacts on display – from late Renaissance books to boardgames of the late-20th century – are rich throughout.

www.arsenale.com

The Making of the Body in Renaissance Venice: Leonardo, Michelangelo, Dürer, Giorgione is a little misleading as a title. These four incredible artists do appear throughout the rooms of Gallerie dell'Accademia, but this deep and rich exploration of the body in art is far more than these men in the subtitle. It’s a presentation that veers from scientific to erotic, realistic to romantic, but one rich and fascinating at every turn. Using our current preoccupation with the body (and the self) as a hook to explore the past, we start by visiting Antonio Rizzo’s handsome Adam, the first monumental nude in Venice, dating from around 1472. But we also witness a carved ivory female anatomical manikin, many da Vinci drawings including of the cardiovascular system, cross-sections of the skull, and the seminal Vitruvian Man, wonderous Dürer works and even 16th century prosthetic limbs, drawings for a steampunk mechanical hand, and even a room of erotic pornography that propelled the early printing industry.

www.gallerieaccademia.it

To Love and Devour, Orta’s potential architectures, AMO/OMA’s diagrams

One of the most unexpected, and perhaps most un-Venetian, exhibitions this year was the newly-opened Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation. At both Biennales we may be used to the rarefied modern art object being artfully placed within an historic palazzo, but here – in a curation by Hans Ulrich Obrist and artist Tolia Astakhishvilli – a building has been stripped back, revealed, rearranged, and operated on as if by a brutal backstreet surgeon, revealing its innards as a space of uncanny distortion, display, and play. To Love and Devour features works from eight other artists in the eclectic arrangement, it’s a site-specificity rarely experienced in this neat city, and all the more enjoyable for it. The first exhibition by the Foundation, and created in situ by Astakhishvili over months in the building, there’s something of a 21st century Gordon Matta Clark in the approach, but instead of trying to carve a clarity and geometric order within chaos, here there is only new complexity and disorder folded into what is found – very much speaking, perhaps, to our world today. Have a look at recessed.space article 00294 for deeper coverage of the show.

www.nf.foundation

The Potential Architecture of Lucy and Jorge Orta is shown at the SPARC* Venice Art Academy – but only as an exhibition slightly overlapping with Biennale, so you’ll need to be quick to see it before it ends on 16 May. If you do get there, you’re in for a treat with several of English artist Lucy Orta’s celebrated architectural-clothing drawings that speak to the body, migration, climate, and survival. Central to the presentation is one of their Antarctica Dome Dwelling tents, a tent for an apolitical, unowned, unspoilt place made of flags from those at risk, attacked, who are now refugees, or are suffering. Shelter is further explored in a series of drawings, models, and glass-blown sculptures that speak to the idea of a growing cell, expanding upon existing buildings to create spaces of security and living.

www.veniceartfactory.org

At Fondazione Prada immaculate vitrines present a rich history of diagrams, spanning centuries, nations, and meaning. Not only the vitrines, but the project is by Rem Koolhaas-founded architects and researchers AMO/OMA and it seeks to explore the history of visual communication, an approach used by the firm in much of their work and drawing. Within the show there are countless rich documents – though, frustratingly many of them are museum reproductions rather than original documents. That said, at moments the presentation sings (especially with a layered-glass vitrine of body diagrams) and offers a valuable resource to visual communicators of all fields. It is not a fun show, though it would be a hard push to make a curation of data playful, but it is rich and deep.

www.fondazioneprada.org

Carlo Scarpa, Scuola Piccola Zattere, SMAC

Carlo Scarpa left more marks in Venice than his work at Querini Stampalia. The Museu Correr, overlooking Saint Mark’s Square, is rich and ornate throughout, but the sequence of spaces redesigned by Carlo Scarpa between 1953 and 1960 are sure to excite many visiting architects. His paired back approach with immaculate and signature detailing is celebrated in a small but interesting exhibition of Scarpa’s original display cases and presentation easels, which may sound unusual – has anybody ever heard of an exhibition of empty vitrines before? – but is a welcome celebration that helps the visitor then read all connecting spaces and displays with a new fluency.

www.correr.visitmuve.it

Another of Venezia’s newer institutions, the Scuola Piccola Zattere is a non-profit space for education and exhibition, its name taken from a uniquely Venetian model of civic organisation that was widespread and inclusive. With exhibitions rooted in the research of invited artists, the current exhibition is by French artist Gaëlle Choisne as part of ongoing research since 2018, and is a rich, playful mingling of the artist’s Haitian heritage – including 18 Haitian artists from a private collection in display alongside Choisne’s own mixed-media works that speak to coiexitence, collaboration, and hospitality.

www.scuolapiccolazattere.com

SMAC – short for San Marco Art Centre – is another new institution, this one occupying the Procuratie Vechie, recently refurbished by David Chipperfield. Here, two exhibitions programmed to coincide with the Architecture Biennale fill the series of terrazzo-floored rooms. On one side, a richly curated show of the modernist architecture of Harry Seidler takes the visitor through the architect’s life, from his 1938 escape from Vienna to Britain, then 1940 refugee internment and deportation to Canada as an ‘enemy alien’ by Winston Churchill, through his later career as one of the most influential modernist architects in Australia. The other wing is an exhibition focussed on the work of South Korean landscape architect Jung Youngsun. It’s informative, if tightly focused on the designer through projects and not wider beliefs and experiences, and as such super-reliant upon drawings and photographs as a mode of display, but any exhibition dedicated to any landscape architect is welcome, especially one so important to recent developments in the sector.

www.smac.org & www.smac.org

Ireland, Luxembourg, Bahrain

We will finish off our roundup of the good from Biennale with three more national pavilions from the Giardini and Arsenale, though ones that push against the grain in this year’s approach. As we will discuss in part two, the Bad of Biennale, much of the exhibition was crowded, intense, noisy, and overly complicated, crammed into small spaces. And so it is interesting that three pavilions stood out by carving moments of calm and relaxation amongst the noise.

Ireland presented Assembly, a simple but meticulously crafted circular chamber designed for local-scale citizens assemblies, where strangers who may otherwise disagree come together to resolve a political issue. It is designed to support such processes as a collaboration between architects, craftspeople, musicians, and writers, and while here is presented as a sculptural form to sit, dwell, and listen in, is easily dismountable and theoretically could travel Ireland offering popup spaces of communication.

In a Biennale dominated by looking, with sight the dominant sense required to navigate the cacophony of stuff, Luxembourg’s deep focus on listening was welcome. A soundscape formed of field recordings across diverse environments critically examined Luxembourgish landscapes, with visitors invited to lay back and let the immersive soundwork float through them. It uses the concept of Ecotone, a transitional space between two ecosystems, to take the listener through the score and find a path through disconnections and co-existences in the presented environments.

Finally, the winner of this year’s Golden Lion for best pavilion similarly created a space that invited slowness, dwelling, and comfort. Bahrain’s Heatwave presented a modular system combining traditional Gulf cooling approaches with contemporary material and environmental research. As an inhabitable space, visitors could move around to feel how architecture creates microclimates through space, material, and form, with passive environmental strategies allowing moments of welcome cooling. It is presented as an experimental space rather than solution, with a mock-up of a geothermal cooling system replicated in the space, cooling the external warm air through underground pipes before releasing it through ceiling orifices. The success of the space couldn’t only be seen through the Golden Lion award, but through the number of people choosing to stop, pause, and remain in the space when the wider Biennale wanted them to speed up and devour the culture on show.