Earth’s empty rooms: Cave diving at Nottingham Contemporary

In an exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary, caves are explored in all their subterrannean, psychological, and other-worldly glory. Caves have been both the surface for & subject of creativity for millenia with this wideranging exploration shedding light into the darkest of space.

On their website, Caruso St. John architects show plans and

section drawings of Nottingham Contemporary, the art gallery they designed, opening

in 2009. It shows the main galleries at the top, with a performance space one

level down, the café beneath, and under that a low-height basement for ventilation

and services. Then the drawing stops, the lowest part of the lift shaft

terminating into the whiteness of the surrounding page.

If the drawing had continued, more spaces would be shown. Nottingham is built upon a labyrinthine network of caves – adjacent to the gallery is an entrance to The City of Caves, a tourist attraction within which a small part of the system can be ventured into. For a short period, however, visitors don’t need to venture in, as caves have been brought to the surface and made visible with an exhibition exploring their relationship to the history of art.

![]()

Hollow Earth: Art, Caves and The Subterranean Imaginary seeks to do more than simply represent an aesthetic of underground realms. Over a series of themed rooms – Threshold, Wall, Dark, City, and Deep – it also dives into the psychology of subterranea, and in doing so offers intriguing artefacts and works considering nature’s ancient architecture.

These spaces are primordial homes for humans and non-humans, they are spaces with a specific threshold, they offer sanctity and protection, and over thousands of years have been adopted by humans to increasingly technological ends, from spaces of the earliest artworks to data storage centres for the relentless output of the internet.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The exhibition opens in an antechamber, a small room containing a tiny page from the 1665 book Mundus Subterraneus, quo universae denique naturae divitiae (The Subterranean World: All its Riches), created by German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. On a trip to Italy, he had been precariously lowered into Vesuvius’ crater, the sublime experience leading him towards his theory of inner-earth networks of interconnected channels of fire, writing that “the whole Earth is not solid but everywhere gaping, and hollowed with empty rooms and spaces, and hidden burrows.” His drawing is a section – going much deeper than Caruso St. John’s – showing a street-pattern-like matrix of fire-tunnels cutting through the dark earth, the surface-level trees and church oblivious to the caves, passages, and fire within.

After this, the theme is threshold. Barry Flanagan’s 1969 series Hole in the Sea show uncanny dark holes centred within a watery screen. The three etchings are derived from still images taken from his film of the same year in which he buried a plastic oil drum in a Dutch beach, then filmed from above as the tide arrived, filled the hole, and dancing around.

The black circle into which the sea nests is a physical threshold, but there are many more within the art object itself, stages a viewer must cross in locating an original artistic event as it is transformed through performance, projection, photograph, then photo etching. The surface of an image is an invitation to dive into unknown creative caves, and it can take serious digging to excavate the layers.

![]()

That double-threshold – of represented physical and the layers of artistic – is also present in René Magritte’s La condition humaine, a 1935 painting drawing from a much earlier artistic rendering, Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and its questioning of where reality and image meet.

Both thresholds have been firmly crossed by the time Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting 1780-81 Grotto in the Gulf of Salerno is encountered. Looking out towards a lone sailing boat – presumably the vessel which delivered the artist to the cave’s opening – cast in hazy moonlight. Most of the canvas is black, the darkness already subsuming the artist deep inside, from where the image was composed.

![]()

With a similar motif of using the mouth of the cave as a frame to look at the world left behind, Caragh Thuring presents a view outwards in which it seems that the cave we are in, despite the psychology of enclosure, darkness, and disappearance, may actually be safer than the external world outside.

As with Wright, the jagged dark edge situates us deep within the cave, but in opposition to Kircher’s theory, the fire and flames are outside, the artist seemingly secured in a kind of sanctity. The world is burning, and in the process seems to have conjured haunted silhouettes of lives once lived, perhaps visitors from Grand Tours past searching for the very truths and knowledge which eventually result in technological prowess and processes that burns the Earth.

![]()

The internal architecture of caves is considered in subsequent galleries. Walls which have etched into and painted over them humankind’s earliest known creative acts are interpreted in work by Elisabeth Pauli, and seen in images of Sofia Borges.

In an installation created for the exhibition, Brazilian artist Borges has created a two-wall mural comprising imagery of a cave wall overlayed with photographs of various artistic objects, including Degas bronzes, in a conflation of source, reshaped matter, reality, and artifice.

![]()

Elisabeth Pauli was one of several artists accompanying German anthropologist Leo Frobenius on early 1930s expeditions around Europe, Indonesia, and Africa. The artists’ job was to carefully record over 5,000 prehistoric paintings in drawings and rubbings.

These images would go on to inspire artists including Alberto Giacometti, Jackson Pollack, and Paul Klee – a process of repeated representation and transformation of source image creating a referential art idea-ecosystem, not unlike an increasingly complex cave network initially accessed through a single small apature.

![]()

There is a paradox of depth and darkness, in that as each increases in magnitude the imagination seems to open up more and more. Perhaps it is a function of the mind to psychologically escape from restriction and find new possibility when chances of escape seem to reduce, in the same way the darkness of our dreams is a canvas for the most unexpected thoughts, dislocated from the physicality of the self. So it is with caves, and as that artistic descent continues through Nottingham Contemporary galleries the ideas of caves begin to map onto our lived, above-ground reality.

Brassaï’s photographs may look like the kind of ancient images Sofia Borges may have replicated, but his photographic Graffiti series of 1950 captures symbols, marks, etchings, and faces carved into the crumbling architecture of Parisian streets. He, as many artists since, can see the cave in the inhabited world, in daylight, in our modern cities and situations without the need to descend into any volcano.

A lithograph created by Henry Moore during the Second World War is said to be of citizens sheltering in Underground stations. But in the work, titled Cavern, it’s hard to make out any identifiable human form in the scrawled darkness, though the fear of the modern world beyond the darkness is palpable. Similarly Burrow, a 2004 Jeff Wall photograph shows a simple black square cut into the ground alongside a pile of dirt and debris. Perhaps it’s a building site, perhaps a grave, whichever, the solid black hole both inviting and repelling.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A series of photographs from the archive of Los Angeles’ Center for Land Use Interpretation documenting the modern use of subterranea spaces in a weird amalgamation of roughly romantic geological surfaces with the mundanity of everyday architecture of late-capitalism. Spaces of storage, business, and logistics compressed into caverns which read like they had been waiting millennia for their function to be realised, but in reality will return to their state as empty, de-humaned spaces of nature in the future, once we have all departed.

As a concave sculpture, Goshka Macuga’s Cave, originally from 1999 and newly recreated in Nottingham, is accessed through a cut in the gallery’s white wall. Inside, a grotto formed of crumbled brown paper is an uncanny and awkward space within which – riffing off artworks drawn onto cave walls from prehistory onwards – the artist locates works by various artist friends. At the centre is Macuga’s own 2021 proposal for the Trafalgar Square Fourth Plinth, a space rocket attached to its red support tower, ready to leave the cave we all inhabit to some other place of the imagination.

![]()

If the drawing had continued, more spaces would be shown. Nottingham is built upon a labyrinthine network of caves – adjacent to the gallery is an entrance to The City of Caves, a tourist attraction within which a small part of the system can be ventured into. For a short period, however, visitors don’t need to venture in, as caves have been brought to the surface and made visible with an exhibition exploring their relationship to the history of art.

fig.i

Hollow Earth: Art, Caves and The Subterranean Imaginary seeks to do more than simply represent an aesthetic of underground realms. Over a series of themed rooms – Threshold, Wall, Dark, City, and Deep – it also dives into the psychology of subterranea, and in doing so offers intriguing artefacts and works considering nature’s ancient architecture.

These spaces are primordial homes for humans and non-humans, they are spaces with a specific threshold, they offer sanctity and protection, and over thousands of years have been adopted by humans to increasingly technological ends, from spaces of the earliest artworks to data storage centres for the relentless output of the internet.

figs.ii-iv

The exhibition opens in an antechamber, a small room containing a tiny page from the 1665 book Mundus Subterraneus, quo universae denique naturae divitiae (The Subterranean World: All its Riches), created by German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. On a trip to Italy, he had been precariously lowered into Vesuvius’ crater, the sublime experience leading him towards his theory of inner-earth networks of interconnected channels of fire, writing that “the whole Earth is not solid but everywhere gaping, and hollowed with empty rooms and spaces, and hidden burrows.” His drawing is a section – going much deeper than Caruso St. John’s – showing a street-pattern-like matrix of fire-tunnels cutting through the dark earth, the surface-level trees and church oblivious to the caves, passages, and fire within.

After this, the theme is threshold. Barry Flanagan’s 1969 series Hole in the Sea show uncanny dark holes centred within a watery screen. The three etchings are derived from still images taken from his film of the same year in which he buried a plastic oil drum in a Dutch beach, then filmed from above as the tide arrived, filled the hole, and dancing around.

The black circle into which the sea nests is a physical threshold, but there are many more within the art object itself, stages a viewer must cross in locating an original artistic event as it is transformed through performance, projection, photograph, then photo etching. The surface of an image is an invitation to dive into unknown creative caves, and it can take serious digging to excavate the layers.

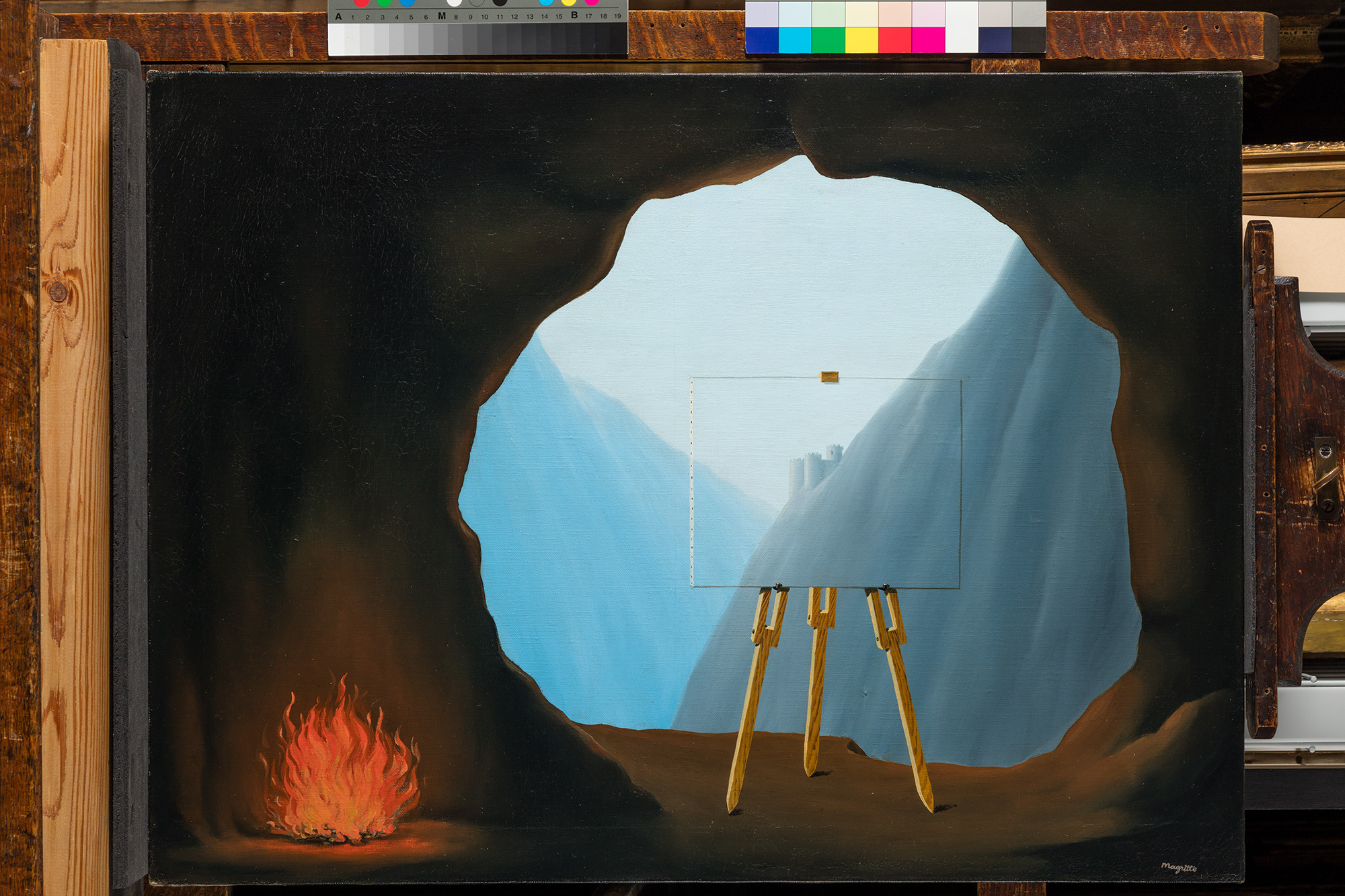

fig.v

That double-threshold – of represented physical and the layers of artistic – is also present in René Magritte’s La condition humaine, a 1935 painting drawing from a much earlier artistic rendering, Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and its questioning of where reality and image meet.

Both thresholds have been firmly crossed by the time Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting 1780-81 Grotto in the Gulf of Salerno is encountered. Looking out towards a lone sailing boat – presumably the vessel which delivered the artist to the cave’s opening – cast in hazy moonlight. Most of the canvas is black, the darkness already subsuming the artist deep inside, from where the image was composed.

fig.vi

With a similar motif of using the mouth of the cave as a frame to look at the world left behind, Caragh Thuring presents a view outwards in which it seems that the cave we are in, despite the psychology of enclosure, darkness, and disappearance, may actually be safer than the external world outside.

As with Wright, the jagged dark edge situates us deep within the cave, but in opposition to Kircher’s theory, the fire and flames are outside, the artist seemingly secured in a kind of sanctity. The world is burning, and in the process seems to have conjured haunted silhouettes of lives once lived, perhaps visitors from Grand Tours past searching for the very truths and knowledge which eventually result in technological prowess and processes that burns the Earth.

fig.vii

The internal architecture of caves is considered in subsequent galleries. Walls which have etched into and painted over them humankind’s earliest known creative acts are interpreted in work by Elisabeth Pauli, and seen in images of Sofia Borges.

In an installation created for the exhibition, Brazilian artist Borges has created a two-wall mural comprising imagery of a cave wall overlayed with photographs of various artistic objects, including Degas bronzes, in a conflation of source, reshaped matter, reality, and artifice.

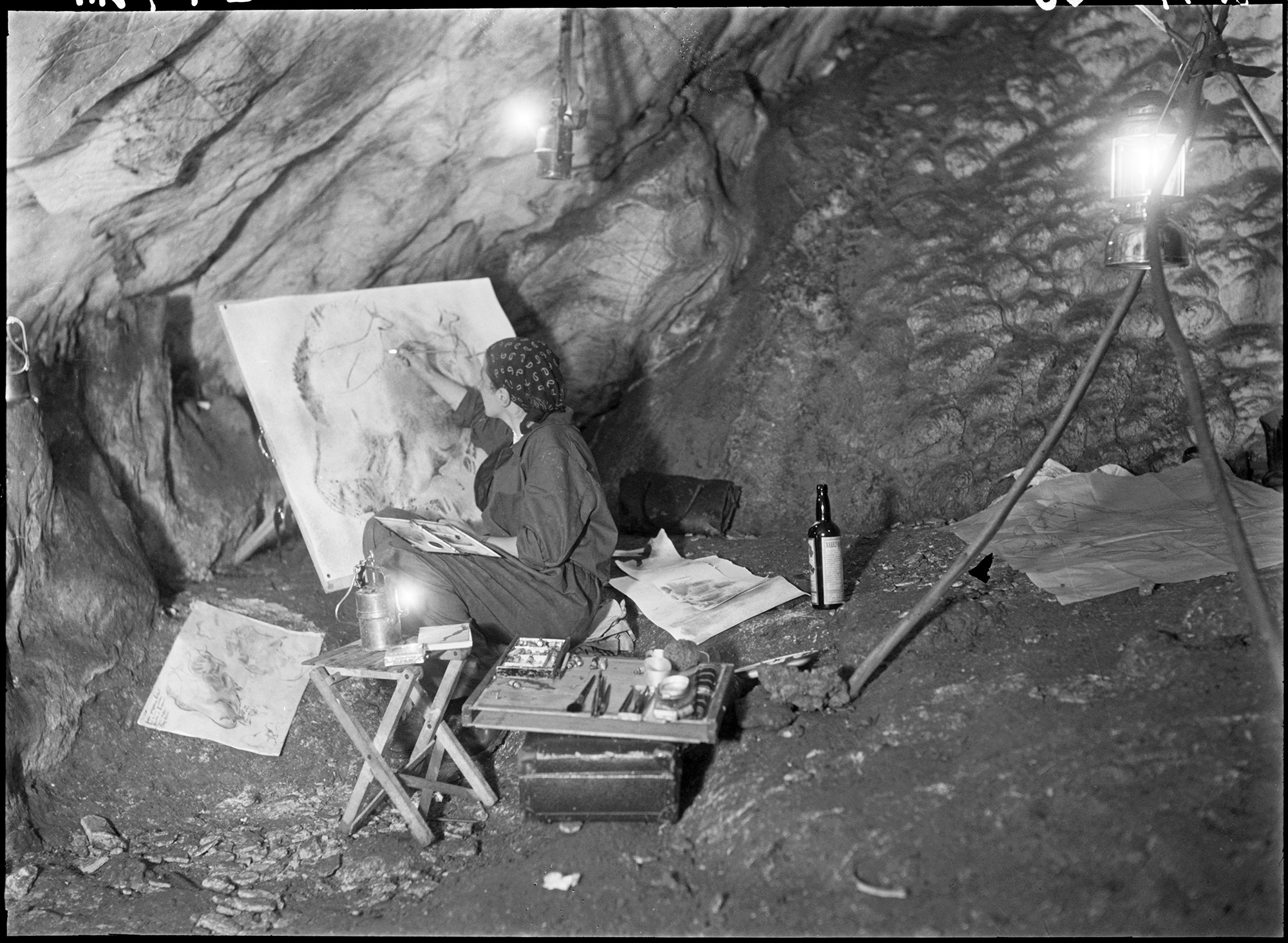

fig.viii

Elisabeth Pauli was one of several artists accompanying German anthropologist Leo Frobenius on early 1930s expeditions around Europe, Indonesia, and Africa. The artists’ job was to carefully record over 5,000 prehistoric paintings in drawings and rubbings.

These images would go on to inspire artists including Alberto Giacometti, Jackson Pollack, and Paul Klee – a process of repeated representation and transformation of source image creating a referential art idea-ecosystem, not unlike an increasingly complex cave network initially accessed through a single small apature.

fig.ix

There is a paradox of depth and darkness, in that as each increases in magnitude the imagination seems to open up more and more. Perhaps it is a function of the mind to psychologically escape from restriction and find new possibility when chances of escape seem to reduce, in the same way the darkness of our dreams is a canvas for the most unexpected thoughts, dislocated from the physicality of the self. So it is with caves, and as that artistic descent continues through Nottingham Contemporary galleries the ideas of caves begin to map onto our lived, above-ground reality.

Brassaï’s photographs may look like the kind of ancient images Sofia Borges may have replicated, but his photographic Graffiti series of 1950 captures symbols, marks, etchings, and faces carved into the crumbling architecture of Parisian streets. He, as many artists since, can see the cave in the inhabited world, in daylight, in our modern cities and situations without the need to descend into any volcano.

A lithograph created by Henry Moore during the Second World War is said to be of citizens sheltering in Underground stations. But in the work, titled Cavern, it’s hard to make out any identifiable human form in the scrawled darkness, though the fear of the modern world beyond the darkness is palpable. Similarly Burrow, a 2004 Jeff Wall photograph shows a simple black square cut into the ground alongside a pile of dirt and debris. Perhaps it’s a building site, perhaps a grave, whichever, the solid black hole both inviting and repelling.

figs.x-xv

A series of photographs from the archive of Los Angeles’ Center for Land Use Interpretation documenting the modern use of subterranea spaces in a weird amalgamation of roughly romantic geological surfaces with the mundanity of everyday architecture of late-capitalism. Spaces of storage, business, and logistics compressed into caverns which read like they had been waiting millennia for their function to be realised, but in reality will return to their state as empty, de-humaned spaces of nature in the future, once we have all departed.

As a concave sculpture, Goshka Macuga’s Cave, originally from 1999 and newly recreated in Nottingham, is accessed through a cut in the gallery’s white wall. Inside, a grotto formed of crumbled brown paper is an uncanny and awkward space within which – riffing off artworks drawn onto cave walls from prehistory onwards – the artist locates works by various artist friends. At the centre is Macuga’s own 2021 proposal for the Trafalgar Square Fourth Plinth, a space rocket attached to its red support tower, ready to leave the cave we all inhabit to some other place of the imagination.

fig.xvi

Throughout the

works on display, the connection between the deep bowels of the earth and

distance of space and technology is everpresent.

Ben Rivers’ 2019 film, Look Then Below –

created in tandem with sci-fi novelist Mark von Schlegell – resonates with that potentially not-so-distant future. Shot in part Somerset’s Wookey Hole caves, he renders a subterranean world in a future where floods have carved into Earth, and in doing so revealed the patina of civilisations past.

With a score by Christina Vantzou, the ghosts of Neolithic settlers live alongside a speculative unknown species which has evolved post-Anthropocene. Caves offer that space of imaginary time travel, past and future collapsed into one in which, through the darkness, psychologies of our self and selves can manifest and, like in Plato’s allegory, offer themselves up for consideration – if we know what we are looking at.

With a score by Christina Vantzou, the ghosts of Neolithic settlers live alongside a speculative unknown species which has evolved post-Anthropocene. Caves offer that space of imaginary time travel, past and future collapsed into one in which, through the darkness, psychologies of our self and selves can manifest and, like in Plato’s allegory, offer themselves up for consideration – if we know what we are looking at.

Nottingham Contemporary is an international centre of

contemporary art with a strong sense of local purpose. Since opening in 2009,

we have held more than 80 exhibitions, with over 2 million visitors to date. We

present innovative and interwoven programmes of international exhibitions,

learning, partnerships, research and new commissions. We are committed to

excellence, experimentation, ambition and innovation. Nottingham Contemporary

was shortlisted for Art Fund Museum of the Year 2019. Nottingham Contemporary

is supported using public funding by Arts Council England and regularly funded

by Nottingham City Council.

www.nottinghamcontemporary.org

Hayward

Gallery Touring organises contemporary art exhibitions that tour to galleries,

museums and other publicly funded venues throughout Britain. In collaboration

with artists, independent curators, writers and partner institutions, Hayward

Gallery Touring develops imaginative exhibitions that are seen by up to half a

million people in over 45 cities and towns each year.

www.southbankcentre.co.uk/touring-programme/hayward-gallery-touring/exhibitions

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.southbankcentre.co.uk/touring-programme/hayward-gallery-touring/exhibitions

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

visit

Hollow Earth: Art, Caves & The Subterranean Imaginary is on at Nottingham Contemporary until 22 January 2023.

More information at:

www.nottinghamcontemporary.org/whats-on/hollow-earth-art-caves-the-subterranean-imaginary

It is a Hayward Gallery Touring exhibition, developed in partnership with Nottingham Contemporary & in collaboration with Glucksman, Cork and RAMM, Exeter, both of which it will travel to in 2023 and 2024.

images

fig.i

Installation view of Hollow Earth: Art, Caves & the

Subterranean Imaginary, 2022, Nottingham Contemporary. Photo Scene

Photography. Courtesy Nottingham Contemporary.

figs.ii-iv

Barry

Flanagan, Hole in the Sea, 1967-70. Black and white photo screen print on paper. Courtesy: Richard Saltoun.

fig.v

René

Magritte, La Condition Humaine, 1935. Oil on canvas. Courtesy: Norwich

Castle. Copyright: ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022.

fig.vi

Joseph

Wright of Derby, Grotto in the Gulf of Salerno, (c.1780-89). Oil on

canvas. Courtesy: Derby Museums Collection.

fig.vii

Caragh

Thuring, Inferno, 2018. Oil on linen. Courtesy: Caragh Thuring

and Thomas Dane Gallery. Copyright: Caragh Thuring.

fig.viii

Installation view of Hollow Earth: Art, Caves & the

Subterranean Imaginary, 2022, Nottingham Contemporary. Photo Scene

Photography. Courtesy Nottingham Contemporary.

fig.ix

Unknown

photographer, Elisabeth Pauli at work in Northern Spain, 1936. Giclee

print. Courtesy: The Frobenius Institute.

fig.x

Center

for Land Use Interpretations, Sub Tropolis Underground, 2017.

Photograph. Courtesy: The Center for Land Use Interpretation.

fig.xi

Center

for Land Use Interpretations, Space Center Executive Park, 2017.

Photograph. Courtesy: The Center for Land Use Interpretation.

fig.xii

Center

for Land Use Interpretations, Sub Tropolis Underground, 2017.

Photograph. Courtesy: The Center for Land Use Interpretation.

fig.xiii

Center

for Land Use Interpretations, Wampum Underground, 2017. Photograph.

Courtesy: The Center for Land Use Interpretation.

fig.xiv

Center

for Land Use Interpretations, Mega Cavern, 2017. Photograph. Courtesy:

The Center for Land Use Interpretation.

fig.xv

Center

for Land Use Interpretations, Gateway Commerce Center, 2017. Photograph.

Courtesy: The Center for Land Use Interpretation.

fig.xvi

Installation view of Hollow Earth: Art, Caves & the

Subterranean Imaginary, 2022, Nottingham Contemporary. Photo Scene

Photography. Courtesy Nottingham Contemporary.

publication date

28 November 2022

tags

Anthropocene, Black, Sofia Borges, Brassaï, Caruso St John, Cave, Cave painting, Center for Land Use Interpretation, Dark, Darkness, Degas, Fire, Barry Flanagan, Fourth Plinth, Leo Frobenius, Glucksman, Grotto, Alberto Giacometti, Hayward Gallery, Athanasius Kircher, Paul Klee, Goshka Macuga, René Magritte, Henry Moore, Nottingham, Nottingham Contemporary, Elisabeth Pauli, Plato, Jackson Pollack, RAMM, Ben Rivers, Science fiction, Space, Subterrannia, Subterrannian, Technology, Threshold, Caragh Thuring, Underground, Vesuvius, Volcano, Mark von Schlegell, Jeff Wall, Joseph Wright of Derby

More information at:

www.nottinghamcontemporary.org/whats-on/hollow-earth-art-caves-the-subterranean-imaginary

It is a Hayward Gallery Touring exhibition, developed in partnership with Nottingham Contemporary & in collaboration with Glucksman, Cork and RAMM, Exeter, both of which it will travel to in 2023 and 2024.