E-WERK

Luckenwalde: a powerful arts centre for the future

A

former power station 30 minutes south of Berlin has found a new use of cultural

– and electrical – production, E-WERK Luckenwalde is a project led by artist

Pablo Wendel and curator Helen Turner, and Will Jennings visited to see (and

hear) what it was all about.

The machinery pounded. An industrial rhythm undercut bass

vibrato seemingly coming from pipes feeding from another room. A variety of

buzzes, hisses, percussive crashes, and metallic impact coalesced into a

crescendo which rose, seemed to move across the room, then drop.

From somewhere else – perhaps down the steep staircase, through the corridor, or carried from one of the many distant, unknown spaces – a droning suggested machinery hard at work. After all, E-WERK Luckenwalde is a power station, crammed with structures and systems of electrical creation, so perhaps it’s no surprise to be experiencing all these by-products of noise and heat.

![]()

However, the noise was not created by the mechanical production of electricity but interventions into the industrial space by sound and material researcher FM Einheit, creating an instrument from what he calls an “elemental castle.” Einheit, a founding member of famed German experimental music group Einstürzende Neubauten (or, in English, Collapsing New Buildings), had visited the former power station three times to explore its percussive and sonic capabilities.

Recording a range of responses, he then turned them into site-responsive installation High on the Wind, a multi-channel work placed around the architecture as if the building, constructed in 1913 but closed after producing its last coal-generated electricity after 1989’s fall of East Germany, had sprung back to life.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In actuality, the power station returned as a space of production after three decades of disuse after artist Pablo Wendel took it over to become his creative studio in 2017. Exhibiting internationally, but not earning enough money to afford his Stuttgart studio’s rising rent, the artist hunted for a new place to make his large-scale sculptural and installation work. That search ended in Luckenwalde, a town about 30 minutes train-ride south of Berlin, which suffered in the former East German post-industrial economy.

“I had never experienced this kind of emptiness – whole villages are empty, like ghost towns,” Wendel says. While this meant he was able to acquire a unique, historically important building, this is not the expected cliché story of an artist benefitting from social and capital abandonment at the expense of the local or standard gentrification.

His power station has since grown not only into a space for making, but also exhibiting, commissioning, hosting residencies, and organising community activities, projects Wendel undertakes with his partner, British curator Helen Turner. Also, and entirely suited to its designed function, E-WERK is also the base of a new kind of electrical generation.

In 2012, Wendel created Kunststrom, a non-profit provider energy provider feeding the German power grid, its energy is available through cooperative distributer Bürgerwerke. Its income supports the refurbishment of their buildings, funding new energy production, and the cultural output presented at E-WERK. Currently, income from electricity sales only makes up a small part of the non-profit’s income alongside state and EU project funding, sales from events, entry, and a gift shop – though this is all pegged at an affordable level. They also have forged a growing network of cultural partnerships with organisations including LUMA Arles and Rupert in Vilnius, both partnering with E-WERK on The Sustainable Institution, a funded residency and symposium series as call to action on economic and ecological change within the cultural sector.

![]()

![]()

![]()

It took Wendel a year to repair, but now a 30m conveyor system running through the building has sprung into life and is used to transport locally sourced waste wood chips into a combustion chamber for a process of wood gasification, the resultant gas then burnt to generate electricity. Charcoal remains are then used across the E-WERK site to rebuild soil or as artistic pigmentation. It is a circular system, though still requiring combustion and not hugely scalable in a residential community is imperfect as an energy solution – but is a start and declaration of intent. There are no plans to a take the power station back up into a full system, but Kunststrom hopes to expand further into sustainable energy production including solar and wind.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Next door to E-WERK is the town’s former swimming pool. The Stadtbad, designed by Bauhaus architect Hans Hertlein, has been closed three decades but it is awaiting a yet unknown cultural use. Having already hosted Lithuanian art opera The Sun and the Sea (see 00036) as well acting as impromptu venue for gigs and flea markets, it is now in Phase 0 of its reimagination. Owned by the municipality and let to E-WERK, a process of collecting stories, memories, ideas, and opinions from surrounding communities has been started ahead of seven years of gradual refurbishment.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The swimming pool will become one component of a growing complex of bottom-up cultural uses. In the power station garden there is already Trafo, a public kitchen/bar pavilion by artist Samuel Treindl, and Fluxdome, a geodesic space which hosts talks and performances. For the opening of E-WERK’s season, FM Einheit performed live – his set commencing with gravel cascading from an industrial conveyor onto a metal sheet, the artist manipulating it before building industrial sounds with metal coil, waste matter, and mechanical tools.

Just two streets away – near enough to still hear the heavy bass from FM Einheit’s rehearsal for the next day’s performance – is Erich Mendelsohn’s Steinberg, Herrmann & Co. Hat Factory, recently restored but also awaiting ideas for future functions. It might become a cultural space, adding to the emerging hub of socially-engaged adaptive reuse around culture and energy alongside the power station, Fluxdome, and Stadtbad – a cultural ecosystem the Sustainable Institution residency programme will work towards.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Whatever programme develops for Luckenwalde, Wendel and Turner are adamant it should not only present progressive and impactful creative projects, but do so alongside and with the local community they have moved into. “I believe you can have international programming that is still accessible locally,” Wendel states, though it is not only culture the pair hope to offer the town: a pair of repurposed petrol pumps were installed in front of E-WERK in 2020, and as a social sculpture they deliver free electricity for residents’ mobile phones, electric bikes, and scooters. It is hoped that over time similar bright yellow pumps might be distributed across Luckenwalde.

Beyond the town, there is potential for E-WERK to build into a wider network of cultural infrastructure powered by, and creating, sustainable energy. Wendel is interested in the relationship between art and infrastructure in Kunststrom – “Where does the artwork end?” he wonders, adding that “the grid could become an instrument itself, or a body.” EWERK offers the provocation for more cultural venues to begin sustainable electrical production as a collective movement of cultural energy. Then, an emergent ecosystem might sustain not only homes and electrical gadgets, but also art, music, and culture. E-WERK is, as Turner puts it, “a prototype for an institution of the future.”

![]()

![]()

From somewhere else – perhaps down the steep staircase, through the corridor, or carried from one of the many distant, unknown spaces – a droning suggested machinery hard at work. After all, E-WERK Luckenwalde is a power station, crammed with structures and systems of electrical creation, so perhaps it’s no surprise to be experiencing all these by-products of noise and heat.

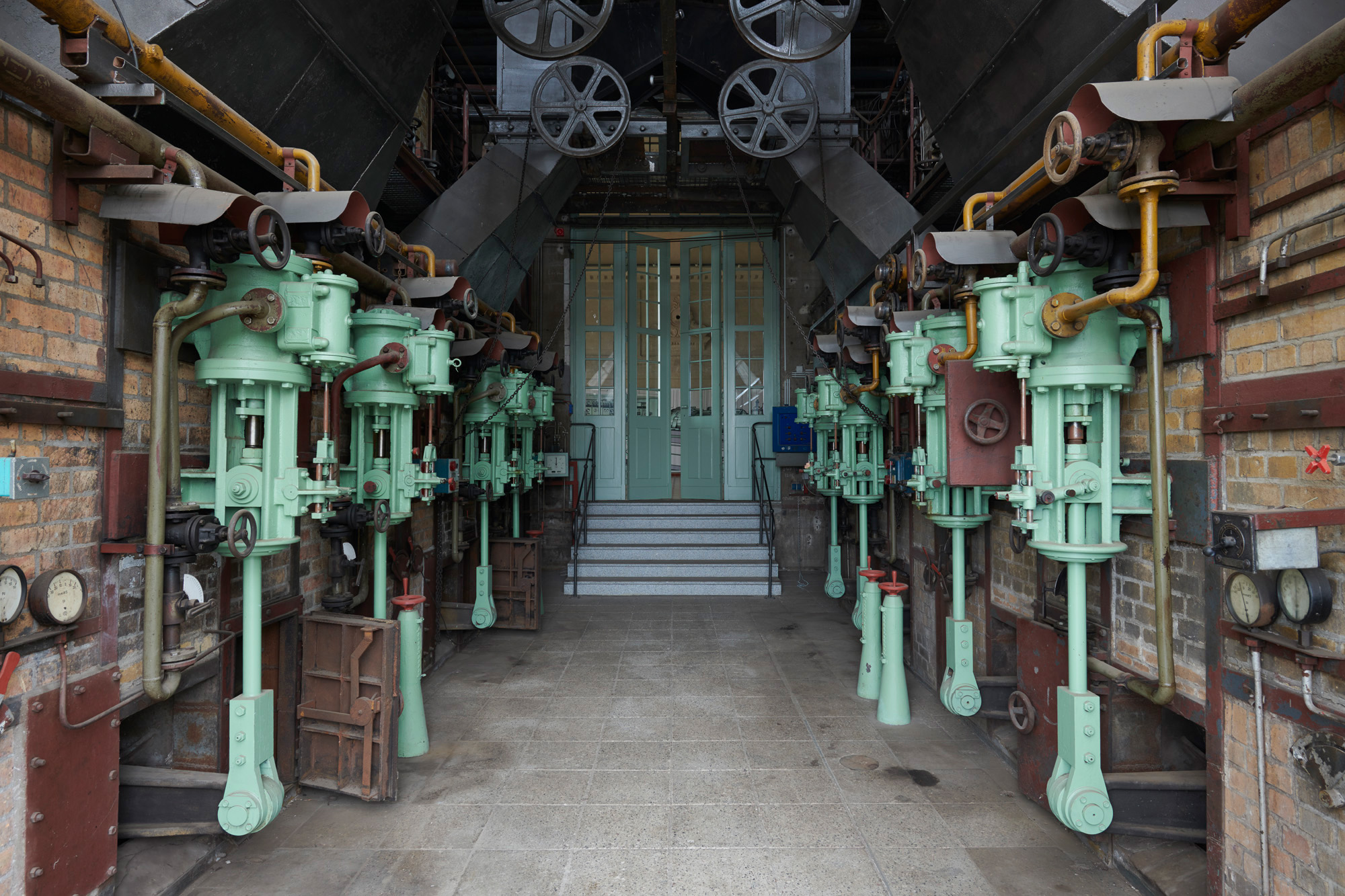

Fig.i

However, the noise was not created by the mechanical production of electricity but interventions into the industrial space by sound and material researcher FM Einheit, creating an instrument from what he calls an “elemental castle.” Einheit, a founding member of famed German experimental music group Einstürzende Neubauten (or, in English, Collapsing New Buildings), had visited the former power station three times to explore its percussive and sonic capabilities.

Recording a range of responses, he then turned them into site-responsive installation High on the Wind, a multi-channel work placed around the architecture as if the building, constructed in 1913 but closed after producing its last coal-generated electricity after 1989’s fall of East Germany, had sprung back to life.

Figs.ii,iii,iv,v

In actuality, the power station returned as a space of production after three decades of disuse after artist Pablo Wendel took it over to become his creative studio in 2017. Exhibiting internationally, but not earning enough money to afford his Stuttgart studio’s rising rent, the artist hunted for a new place to make his large-scale sculptural and installation work. That search ended in Luckenwalde, a town about 30 minutes train-ride south of Berlin, which suffered in the former East German post-industrial economy.

“I had never experienced this kind of emptiness – whole villages are empty, like ghost towns,” Wendel says. While this meant he was able to acquire a unique, historically important building, this is not the expected cliché story of an artist benefitting from social and capital abandonment at the expense of the local or standard gentrification.

His power station has since grown not only into a space for making, but also exhibiting, commissioning, hosting residencies, and organising community activities, projects Wendel undertakes with his partner, British curator Helen Turner. Also, and entirely suited to its designed function, E-WERK is also the base of a new kind of electrical generation.

In 2012, Wendel created Kunststrom, a non-profit provider energy provider feeding the German power grid, its energy is available through cooperative distributer Bürgerwerke. Its income supports the refurbishment of their buildings, funding new energy production, and the cultural output presented at E-WERK. Currently, income from electricity sales only makes up a small part of the non-profit’s income alongside state and EU project funding, sales from events, entry, and a gift shop – though this is all pegged at an affordable level. They also have forged a growing network of cultural partnerships with organisations including LUMA Arles and Rupert in Vilnius, both partnering with E-WERK on The Sustainable Institution, a funded residency and symposium series as call to action on economic and ecological change within the cultural sector.

Figs.vi,vii,viii

Another collaboration, led to the presentation of films by

Agnes Denes in a small gallery. CIRCA presented the same films in advertising

screens around the world, including London’s Piccadilly Circus. Short videos

strum through Denes’ projects, speaking not only to the 1980s and 90s in which

they were made, but also the current anthropocenic predicament. Denes’ Wheatfield

– A Confrontation (1982) saw a field of wheat spring up and get harvested

in the shadow of New York’s World Trade Centre, while later for Tree

Mountain the artist formed an elliptical planting of 11,000 trees over the

peak of a former gravel pit in Finland.

Those trees are now in adolescence. It is a slow artwork, just as the E-WERK building is itself. “You’re just a small part of the life of a building,” Wendel says, his slow refurbishment designed to support its growing current cultural uses but also celebrate its civic and architectural past and prepare it for unknown futures. Most of the old machinery has been largely silent until Einheit’s activation, but some elements had been returned to Kunststrom power production.

Those trees are now in adolescence. It is a slow artwork, just as the E-WERK building is itself. “You’re just a small part of the life of a building,” Wendel says, his slow refurbishment designed to support its growing current cultural uses but also celebrate its civic and architectural past and prepare it for unknown futures. Most of the old machinery has been largely silent until Einheit’s activation, but some elements had been returned to Kunststrom power production.

It took Wendel a year to repair, but now a 30m conveyor system running through the building has sprung into life and is used to transport locally sourced waste wood chips into a combustion chamber for a process of wood gasification, the resultant gas then burnt to generate electricity. Charcoal remains are then used across the E-WERK site to rebuild soil or as artistic pigmentation. It is a circular system, though still requiring combustion and not hugely scalable in a residential community is imperfect as an energy solution – but is a start and declaration of intent. There are no plans to a take the power station back up into a full system, but Kunststrom hopes to expand further into sustainable energy production including solar and wind.

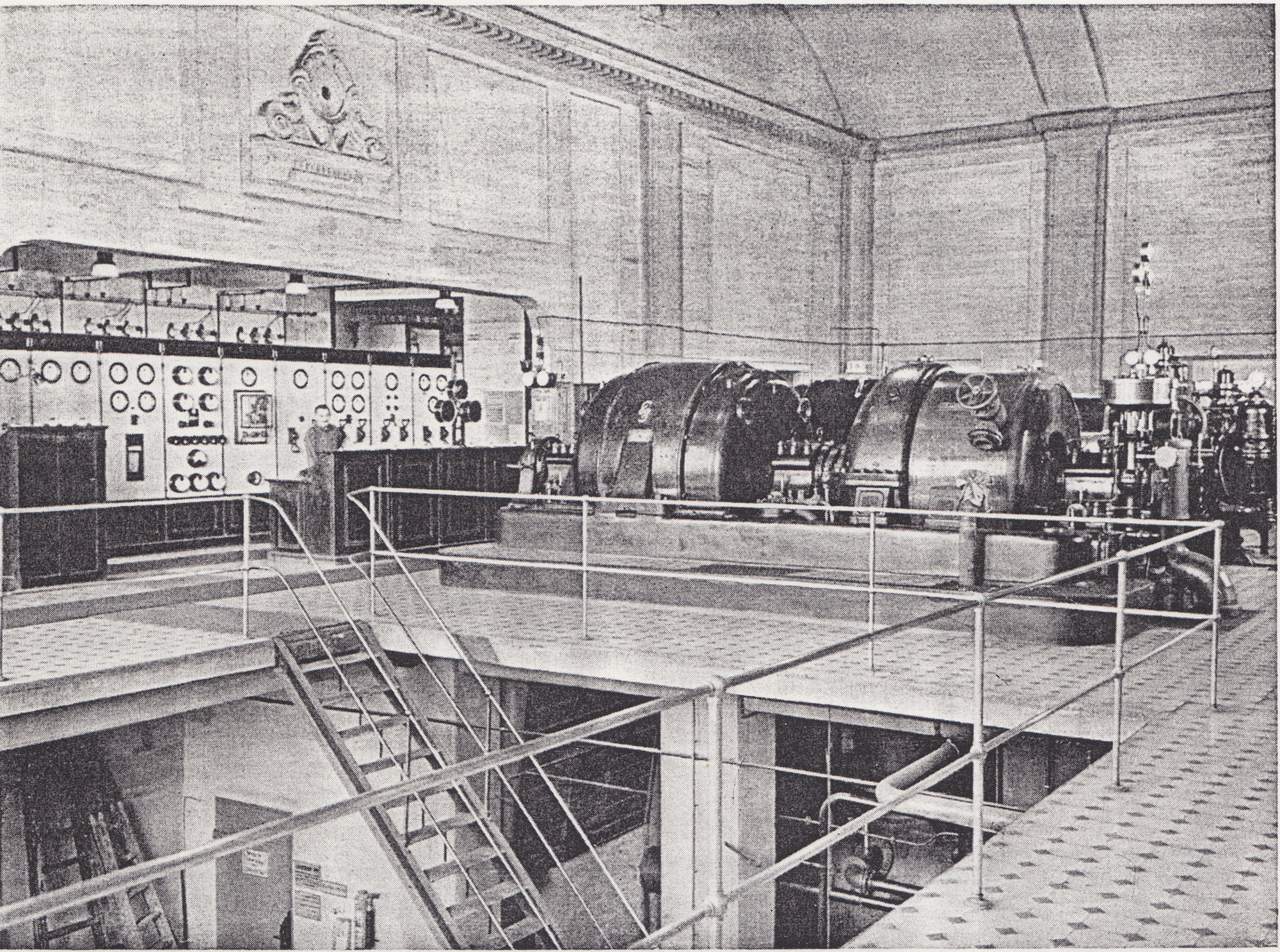

Figs.ix,x,xi,xii

When a fully-functioning power station, main combustion took

place in a grand central combustion hall replete with smart floor tiles,

classical detailing, and a coffered ceiling letting light in and fumes out. Today

it is the main exhibition space, currently occupied by The Throat is a

Threaded Melody, an exhibition of uncanny and ad-hoc cyborg characters created

by Kira Freije. Formed of found materials and metal, the death-mask-like faces

are casts of the artists friends, some of whom studied with her at London’s

Royal Academy Schools. A moveable gantry traversing the space is still

operable, with one of Freije’s sculptures suspended from its hefty hook.

Next door to E-WERK is the town’s former swimming pool. The Stadtbad, designed by Bauhaus architect Hans Hertlein, has been closed three decades but it is awaiting a yet unknown cultural use. Having already hosted Lithuanian art opera The Sun and the Sea (see 00036) as well acting as impromptu venue for gigs and flea markets, it is now in Phase 0 of its reimagination. Owned by the municipality and let to E-WERK, a process of collecting stories, memories, ideas, and opinions from surrounding communities has been started ahead of seven years of gradual refurbishment.

Figs.xiii,xiv,xv

The swimming pool will become one component of a growing complex of bottom-up cultural uses. In the power station garden there is already Trafo, a public kitchen/bar pavilion by artist Samuel Treindl, and Fluxdome, a geodesic space which hosts talks and performances. For the opening of E-WERK’s season, FM Einheit performed live – his set commencing with gravel cascading from an industrial conveyor onto a metal sheet, the artist manipulating it before building industrial sounds with metal coil, waste matter, and mechanical tools.

Just two streets away – near enough to still hear the heavy bass from FM Einheit’s rehearsal for the next day’s performance – is Erich Mendelsohn’s Steinberg, Herrmann & Co. Hat Factory, recently restored but also awaiting ideas for future functions. It might become a cultural space, adding to the emerging hub of socially-engaged adaptive reuse around culture and energy alongside the power station, Fluxdome, and Stadtbad – a cultural ecosystem the Sustainable Institution residency programme will work towards.

Figs.xvi,xvii,xviii,xix

Whatever programme develops for Luckenwalde, Wendel and Turner are adamant it should not only present progressive and impactful creative projects, but do so alongside and with the local community they have moved into. “I believe you can have international programming that is still accessible locally,” Wendel states, though it is not only culture the pair hope to offer the town: a pair of repurposed petrol pumps were installed in front of E-WERK in 2020, and as a social sculpture they deliver free electricity for residents’ mobile phones, electric bikes, and scooters. It is hoped that over time similar bright yellow pumps might be distributed across Luckenwalde.

Beyond the town, there is potential for E-WERK to build into a wider network of cultural infrastructure powered by, and creating, sustainable energy. Wendel is interested in the relationship between art and infrastructure in Kunststrom – “Where does the artwork end?” he wonders, adding that “the grid could become an instrument itself, or a body.” EWERK offers the provocation for more cultural venues to begin sustainable electrical production as a collective movement of cultural energy. Then, an emergent ecosystem might sustain not only homes and electrical gadgets, but also art, music, and culture. E-WERK is, as Turner puts it, “a prototype for an institution of the future.”

Figs.xx,xxi

E-WERK Luckenwalde is located in a former coal power station built in 1913, ceasing

production in 1989 after the fall of the Berlin wall. Located 30 minutes south of Berlin,

Brandeburg, E-WERK Luckenwalde is jointly directed by artist Pablo Wendel and curator Helen

Turner. In 2017, the art collective Performance Electrics gGmbH led by Pablo Wendel acquired

the former brown-coal power station with the vision to reanimate it as a sustainable Kunststrom

(art power) Kraftwerk to feed power into the national grid by burning locally sources waste wood

chips to make electricity, and function as a large scale contemporary art centre. As part of POWER NIGHT in 2019, Performance Electrics gGmbH formally switched the power in the

former factory back on. Since 2019, E-WERK Luckenwalde has curated and commissioned an

annual contemporary art programme exhibiting artists including Lindsay Seers, Keith Sargent, Arantxa Etcheverria, Adelina Ivan and Alina Popa, Peles Empire, Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, Cooking Sections, Karrabing Film Collective, Isabel Lewis & Sissel Tolaas, Tabita

Rezaire and Himali Singh Soin, Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė and Lina Lapelytė, Lamin

Fofana, Keiken, Henrike Naumann, Jenna Sutela, Lauryn Youden, L. Zylberberg, Peles Empire, Kira Freije, Michelle Williams Gamaker, Isabel Lewis, Paul Maheke, Harold Offeh, Bik Van der

Pol, Nicolas Deshayes, Performance Electrics gGmbH, Lucy Joyce, umschichten, Nina Beier,

Cecilia Bengolea with Craig Black Eagle, Performance Electrics, marikiscrycrycry in collaboration with Gareth Chambers, Charismatic Megafauna, Fernanda Muñoz-Newsome with

India Harvey and Josh Antonia Grigg, Rowdy SS and Nora Turato.

www.kunststrom.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.willjennings.info

visit

Find out more about how to visit E-WERK Luckenwalde, their exhibitions, and details on Kunststrom here:

www.kunststrom.com

images

fig.i,xx E-WERK Luckenwalde aerial photograph (2019).

©

E-WERK Luckenwalde and Tim Haber

figs.ii,iv E-WERK Engine Room (2019).

©

Ben Westoby and E-WERK Luckenwalde

figs.iii,v E-WERK interiors, lit for FM Einheit installation (2023). © Will Jennings

fig.vi E-WERK Luckenwalde Turbinenhalle circa 1928, archive image.

© E-WERK Luckenwalde

fig.vii E-WERK Luckenwalde entrance (2019).

©

E-WERK Luckenwalde and Ben Westoby.

fig.viii E-WERK Luckenwalde Exterior circa 1928, archive image.

©

E-WERK Luckenwalde

figs.ix-xii E-WERK Luckenwalde, Kira Freije, The Material Revolution (2023).

©

Mathias_Voelzke.

fig.xiii Himali Singh Soin performance (2022). Image courtesy of Stefan Korte and E-WERK Luckenwalde.

fig.xiv Stadtbad interior (2023). © Will Jennings

fig.xv FM Einheit performance at E-WERK (2023). © Will Jennings

fig.xvi Studio Olafur Eliasson Kitchen workshop (2021). Image courtesy of SOE Kitchen and E-WERK Luckenwalde.

fig.xvii Erich Mendelsohn’s

Steinberg, Herrmann & Co. Hat Factory (2023)

© Will Jennings

fig.xviii Performance Electrics, Super Kunststrom (2020). Image courtesy of Stefan Korte and E-WERK Luckenwalde.

fig.xix People gathering at E-WERK. Image courtesy of Stefan Korte and E-WERK Luckenwalde.

fig.xxi Pablo Wendel and Helen Turner (2021).

©

Diana Pfammatter.

publication date

17 May 2023

tags

Anthropocene, Art centre, Berlin, CIRCA, Agnes Denes, East

Germany, Einstürzende Neubauten, Electricity, E-WERK, FM Einheit, Kira Freije,

Gallery, Germany, Industry, Infrastructure, Will Jennings, Kunststrom,

Luckenwalde, Luma Arles, Machinery, Erich Mendelsohn, Network, Performance,

Post-industrial, Power, Power station, Rupert, Stadtbad, Sound art, The Sun and

the Sea, Samuel Treindl, Helen Turner, Pablo Wendel

www.kunststrom.com