From Kinga Oktabska’s studio: fragmented landscapes & found histories

Kinga Oktabska is an

artist well-placed to consider the forces of change in both the River Thames

and the capital’s gentrification, having been awarded free studio space in Battersea, London, from cultural charity Hypha Studios. Following a recent community workshop,

and ahead of an Open Studios, she considers her creative practice and the shifting

landscape it explores.

Battersea's riverfront is a landscape of rebirth and oblivion.

It’s woven from water, glass, and rust. Embroidered with crane lights, studded

with silted bolts. Once an imperial warehouse, today a repository for capital

assets. Luxury flats are

built over the rotten planks of industrial wharfs, stretching between the

crests of rise and fall. Far above, the angels sprinkle ashes over the city’s

latest monoliths.

Among the changes in the land surrounding it, and the functions assigned to it throughout the years, the river is the constant variable in this ongoing transformation. Lifting its veil at low tide, the Thames appears as an archive of ever-growing memory, unearthing layers erased from the new urban fabric. Discarded waste and rubble, industrial fossils, mix with clay to form sediments in the river shore strata. With a bit of luck and imagination, you can find fingerprints of factory workers in the texture of bricks, design mechanisms from parts of engines and pipes, and craft mosaics from the pieces of porcelain. It is these relics of the lost worlds that keep bringing me back to the riverbank, like the memory of childhood, or dreams of landscapes hidden in the past.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Lower Silesia, the south-western region of Poland where I come from, is a patchwork of old and new. It is a place where abandoned mansions sit next-door to pistachio-coloured houses, the ruins of a bunker hide at the back of a football pitch, and dismembered German surnames lay to rest behind polished gravestones. I remember walking past skeletons of disused factories on my way to school, bas-reliefs and satellite discs, and baroque figures of amputee saints bowing to the shining Virgin. And the hills in the middle of the plains, bumps filled with post-war rubble, covered with a thin layer of grass and daisies. In the fundaments of its rebirth, of a new life less than 80 years old, it seemed to be marked with traces of its previous lives. Some of these lives were cursed, eradicated from memory in compliance with Polonization, others neatly restored and entered on the lists of national heritage.

My grandparents came from mainland Poland to the Recovered Territories sometime after the end of World War II. They settled in a post-German tenement in a small town in Lower Silesia – after the end of the war, Germans were evicted from the area, often forced to move out suddenly. Homes were stuffed into suitcases for those departing and arriving. Left behind were objects waiting to be adopted: dinner tables, agricultural tools, curtains, quilts, kitchen pots.

Some houses were haunted. These were burned or left to overgrow with weeds, the forsaken belongings buried in the backyards or drowned in the river. I remember a neighbour who was visited by a ghost of a German soldier every night: she learned to share the home with him, and store her fur coats in his closet.

Fragments, layers of wallpaper, objects from another era or land were clues to discover the past. It was a kind of a game to me. I remember imagining myself in some other time, thinking of who I might have been here, what the fallen roofs were once guarding. And this landscape was so complete, so multidimensional. As I fell asleep, I wished to dream of them again.

![]()

![]()

![]()

I think a part of settling in a new place is turning its scenes into memories of home. Maybe in this way we keep a part of the place for ourselves, creating our own interpretation of it: we make symbols out of street corners, trees, or plaster faces above windows. When I moved to Battersea, in the midst of the pandemic, I would take long walks across the riverside. The further upstream, towards Nine Elms, the more sterile and unfamiliar it seemed, like a scenography of a video game where you have to follow a precisely marked path.

The river’s shore seemed like an exemption from these rules: a remote land that cannot be squeezed any further, flooded and barren, subject to the forces of the moon. I was drawn to glimpses of lost worlds, watching them stray in the shadows of growing towers. These fragments felt fragile, transient, yet indestructible. Tidal matter carried blocks of an alternative landscape, the story of a life cut from the horizon, like pieces of memory waiting to be re-remembered. I found myself returning to the urban ruins, imagining what they were and what they could become. I wanted to find out whose stories they were.

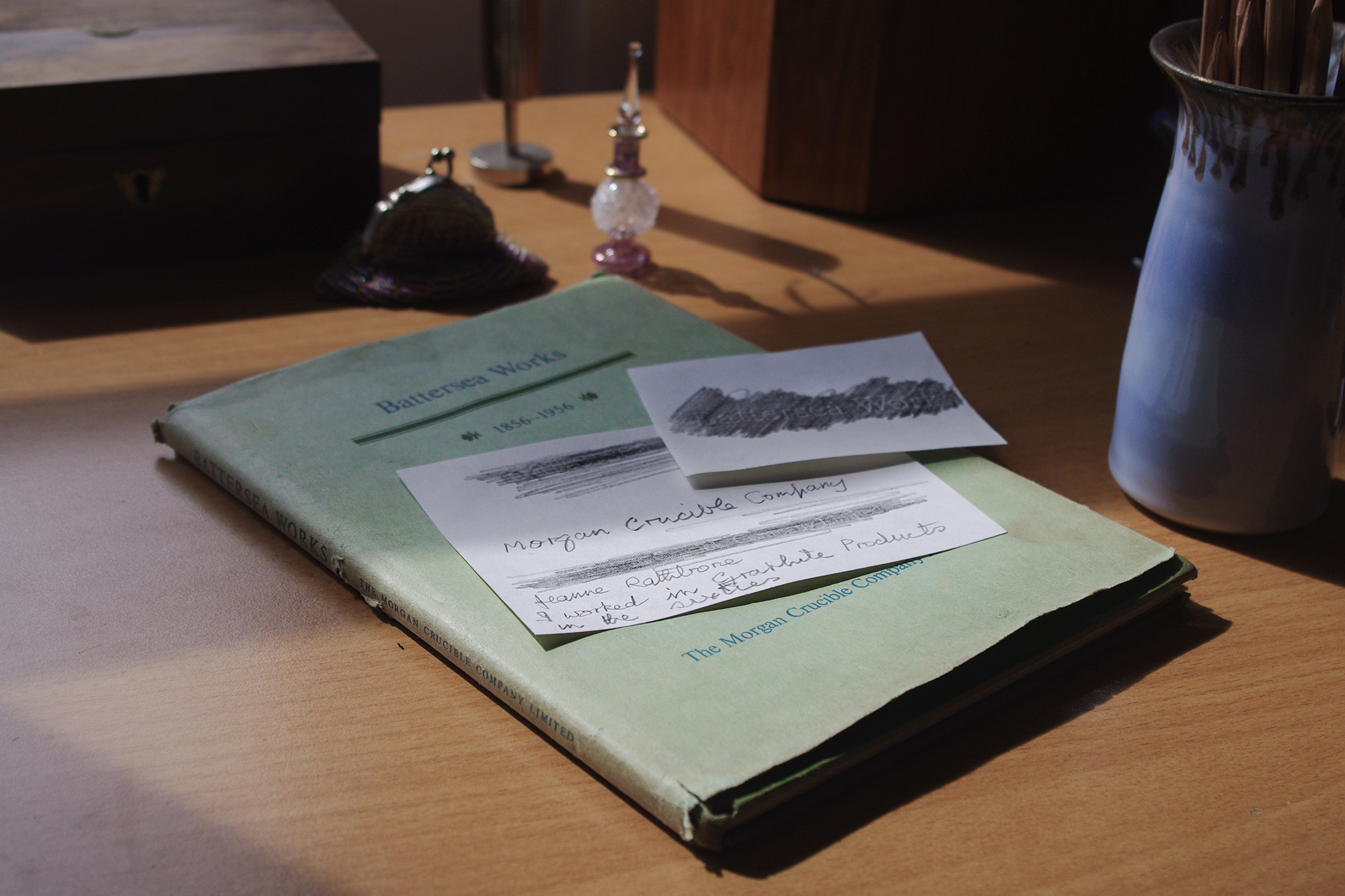

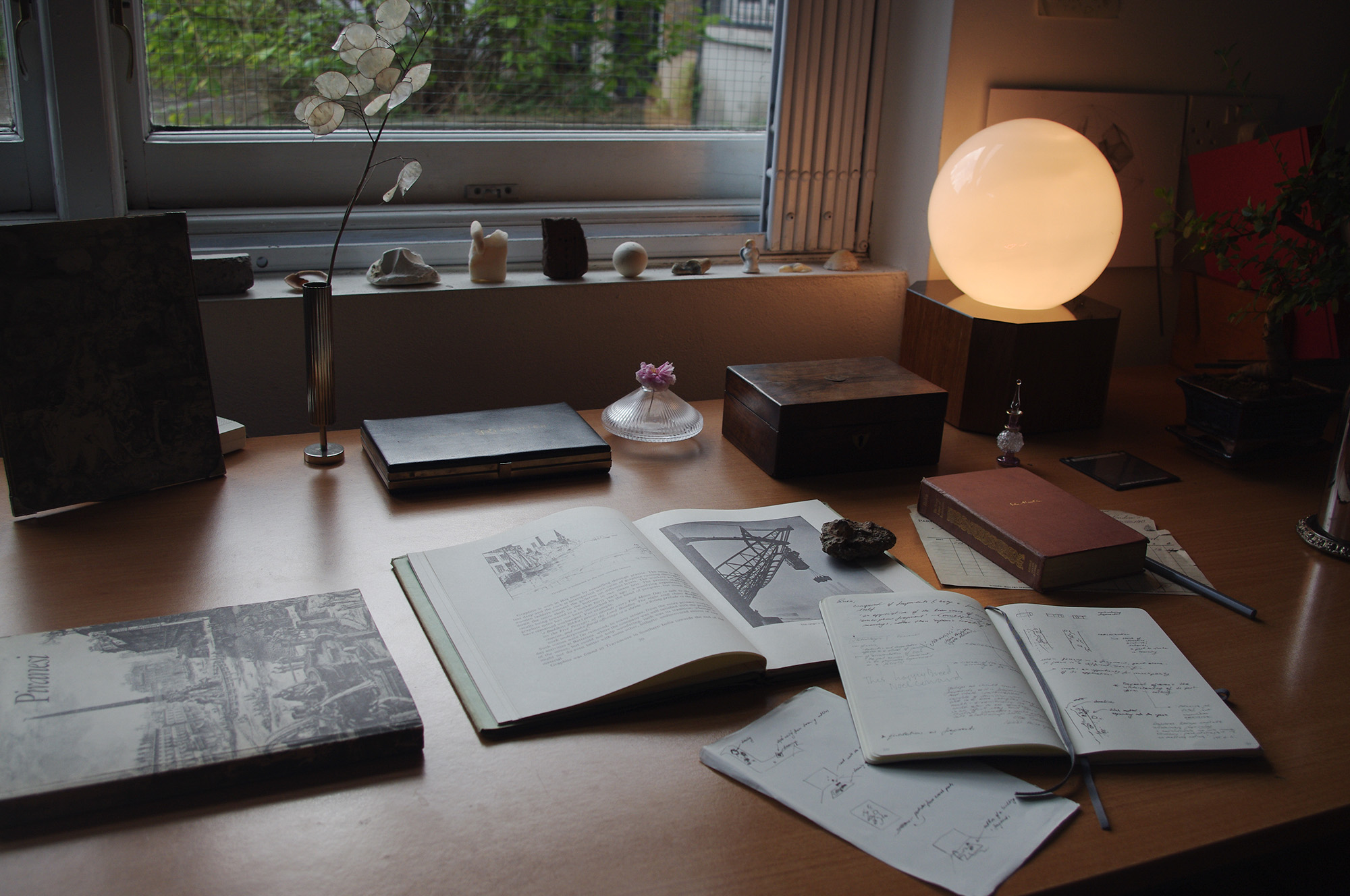

I visited the library, looked for mementos in antique shops, spoke with older generations of locals who remembered a different scene. Battersea’s industrial landscape has been largely erased and forgotten, appearing only in fragments of photographs, memories, documents, and discarded objects. I saw these fragments as contours, forms, worlds that felt important to piece together. The matter of history became the material I was working with. I started finding colours in pebbles and bricks, turning them into pigments, forming drawing styluses from pieces of metal reclaimed from the river shore. As I drew, I let the objects tell their stories in marks embedded in wood, transforming the invisible into a physical form.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Two hundred years ago, at the end of my road, there was a Silk Factory. It produced textiles which were transported by river across the country, woven by hands which once drew lines in the sand on the shore. Today, its story has been erased and built over – luxury apartments now stand there while residents tread unknowingly over foundations and memories that slip ever deeper into the river.

Working with dress historian and practitioner Pawel Tomaszewski, I recently organised a workshop which invited guests to recover the heritage of the area and its lost crafts. Together, we used discarded objects from the shore to create graphite and metalpoint drawings, and learned to experiment with the weaving processes. Our discussions brought together local residents, an architect, and a former factory worker. The workshop became a space to share experiences and memories; to take the fragments we each carried and turn them into something new.

The process of assigning a new function to obsolete objects created an opportunity for reconfiguration of their meaning and value. In between warps and wefts, shells and bricks, silver and copper, new landscapes of Battersea were coming to life. I am now working on weaving the drawings together into a collaborative artwork, building layers of lines and forms from fragments narrated by multiple hands.

In an era of accelerating changes to our urban landscapes, relics of the past can be seen in opposition to the new. But small fragments of forgotten lives can revivify entire societies, awake a blurry lane of our memory; we create rituals of commemoration around small pieces of earth and bone; or at times, we simply sweep away the dust in an attempt to forget. Looking at the past through the lens of a fragment gives us agency to relearn history: uncover diversity of meanings, buried layers of a grand narrative, which today’s tide will map out anew.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Among the changes in the land surrounding it, and the functions assigned to it throughout the years, the river is the constant variable in this ongoing transformation. Lifting its veil at low tide, the Thames appears as an archive of ever-growing memory, unearthing layers erased from the new urban fabric. Discarded waste and rubble, industrial fossils, mix with clay to form sediments in the river shore strata. With a bit of luck and imagination, you can find fingerprints of factory workers in the texture of bricks, design mechanisms from parts of engines and pipes, and craft mosaics from the pieces of porcelain. It is these relics of the lost worlds that keep bringing me back to the riverbank, like the memory of childhood, or dreams of landscapes hidden in the past.

Lower Silesia, the south-western region of Poland where I come from, is a patchwork of old and new. It is a place where abandoned mansions sit next-door to pistachio-coloured houses, the ruins of a bunker hide at the back of a football pitch, and dismembered German surnames lay to rest behind polished gravestones. I remember walking past skeletons of disused factories on my way to school, bas-reliefs and satellite discs, and baroque figures of amputee saints bowing to the shining Virgin. And the hills in the middle of the plains, bumps filled with post-war rubble, covered with a thin layer of grass and daisies. In the fundaments of its rebirth, of a new life less than 80 years old, it seemed to be marked with traces of its previous lives. Some of these lives were cursed, eradicated from memory in compliance with Polonization, others neatly restored and entered on the lists of national heritage.

My grandparents came from mainland Poland to the Recovered Territories sometime after the end of World War II. They settled in a post-German tenement in a small town in Lower Silesia – after the end of the war, Germans were evicted from the area, often forced to move out suddenly. Homes were stuffed into suitcases for those departing and arriving. Left behind were objects waiting to be adopted: dinner tables, agricultural tools, curtains, quilts, kitchen pots.

Some houses were haunted. These were burned or left to overgrow with weeds, the forsaken belongings buried in the backyards or drowned in the river. I remember a neighbour who was visited by a ghost of a German soldier every night: she learned to share the home with him, and store her fur coats in his closet.

Fragments, layers of wallpaper, objects from another era or land were clues to discover the past. It was a kind of a game to me. I remember imagining myself in some other time, thinking of who I might have been here, what the fallen roofs were once guarding. And this landscape was so complete, so multidimensional. As I fell asleep, I wished to dream of them again.

I think a part of settling in a new place is turning its scenes into memories of home. Maybe in this way we keep a part of the place for ourselves, creating our own interpretation of it: we make symbols out of street corners, trees, or plaster faces above windows. When I moved to Battersea, in the midst of the pandemic, I would take long walks across the riverside. The further upstream, towards Nine Elms, the more sterile and unfamiliar it seemed, like a scenography of a video game where you have to follow a precisely marked path.

The river’s shore seemed like an exemption from these rules: a remote land that cannot be squeezed any further, flooded and barren, subject to the forces of the moon. I was drawn to glimpses of lost worlds, watching them stray in the shadows of growing towers. These fragments felt fragile, transient, yet indestructible. Tidal matter carried blocks of an alternative landscape, the story of a life cut from the horizon, like pieces of memory waiting to be re-remembered. I found myself returning to the urban ruins, imagining what they were and what they could become. I wanted to find out whose stories they were.

I visited the library, looked for mementos in antique shops, spoke with older generations of locals who remembered a different scene. Battersea’s industrial landscape has been largely erased and forgotten, appearing only in fragments of photographs, memories, documents, and discarded objects. I saw these fragments as contours, forms, worlds that felt important to piece together. The matter of history became the material I was working with. I started finding colours in pebbles and bricks, turning them into pigments, forming drawing styluses from pieces of metal reclaimed from the river shore. As I drew, I let the objects tell their stories in marks embedded in wood, transforming the invisible into a physical form.

Two hundred years ago, at the end of my road, there was a Silk Factory. It produced textiles which were transported by river across the country, woven by hands which once drew lines in the sand on the shore. Today, its story has been erased and built over – luxury apartments now stand there while residents tread unknowingly over foundations and memories that slip ever deeper into the river.

Working with dress historian and practitioner Pawel Tomaszewski, I recently organised a workshop which invited guests to recover the heritage of the area and its lost crafts. Together, we used discarded objects from the shore to create graphite and metalpoint drawings, and learned to experiment with the weaving processes. Our discussions brought together local residents, an architect, and a former factory worker. The workshop became a space to share experiences and memories; to take the fragments we each carried and turn them into something new.

The process of assigning a new function to obsolete objects created an opportunity for reconfiguration of their meaning and value. In between warps and wefts, shells and bricks, silver and copper, new landscapes of Battersea were coming to life. I am now working on weaving the drawings together into a collaborative artwork, building layers of lines and forms from fragments narrated by multiple hands.

In an era of accelerating changes to our urban landscapes, relics of the past can be seen in opposition to the new. But small fragments of forgotten lives can revivify entire societies, awake a blurry lane of our memory; we create rituals of commemoration around small pieces of earth and bone; or at times, we simply sweep away the dust in an attempt to forget. Looking at the past through the lens of a fragment gives us agency to relearn history: uncover diversity of meanings, buried layers of a grand narrative, which today’s tide will map out anew.

Kinga Oktabska is an artist from

Wroclaw, Poland, living & working in London. She is currently an artist in

residence at Hypha Studios in Battersea. Her practice considers landscapes lost

in a time of accelerating social change & aims to reconstruct the narrative

of a place from traces that have been erased, imagined, or that are invisible to

the eye. Her methodology is to discover landscape through found objects & local memory. Searching the shores of the Thames, she crafts her styluses from

discarded metals & turns bricks & rivershore debris into pigments. Dust

becomes a metaphor: something unseen & marginalised, it is a medium for

exploring forgotten histories, with agency to construct alternative landscapes.

Through her work, she explores how art can disseminate local history and

empower communities facing regenerative change, critiquing the underlying value

systems of regeneration altogether.

www.kingaoktabska.com

Hypha Studios is a charity matching

creatives with empty spaces & regenerating the high street with cultural

hubs & events for local communities. By providing free studios &

project space we act as an incubator for creatives to test new ideas without

financial obstacles. We provide opportunities to those who might not be able to

access space, support or visibility. In return for the free space, creatives

organise public events, supporting the locality & benefiting the high

street.

Hypha Studios emerged as an idea during the

pandemic, prompted by the three-sided problem of increasing high street

vacancies, loss of community spaces and deteriorating conditions for artists

& creatives. Founded by Camilla Cole & (editor of recessed.space) Will Jennings, the non-profit

organisation was set up with three core objectives: one, to bring culture & engagements in the arts to the public throughout the UK; two, to help

landowners keep their assets alive through an injection of local creativity;

& three, to help artists unlock new bounds of creativity by unlocking vacant

units, free of charge.

www.hyphastudios.com

Hypha Studios emerged as an idea during the pandemic, prompted by the three-sided problem of increasing high street vacancies, loss of community spaces and deteriorating conditions for artists & creatives. Founded by Camilla Cole & (editor of recessed.space) Will Jennings, the non-profit organisation was set up with three core objectives: one, to bring culture & engagements in the arts to the public throughout the UK; two, to help landowners keep their assets alive through an injection of local creativity; & three, to help artists unlock new bounds of creativity by unlocking vacant units, free of charge.

www.hyphastudios.com

images

Kinga Oktabska is hosting an open studio on 20 September 2023, 12-9pm at her Hypha Studios space in Battersea. She will showcase collaborative artwork, bringing together drawing and weaving fragments created at the recent ‘Silk & Rubble’ workshop.

Show your interest in attending here:

www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/open-studio-tickets-718529951427

images

All images © Kinga Oktabska

publication date

18 September 2023

tags

Battersea, Brick, Community, Development, Drawing, Factory, Fragments, Gentrification, Hypha Studios, Landscape, Lower Silesia, Metalpoint, Mudlarking, Nine Elms, Kinga Oktabska, Pebbles, Pipes, Poland, Porcelain, Property, River, River Thames, Rubble, Silk, Stories, Studio, Thames, Tide, Pawel Tomaszewski, Waste

Show your interest in attending here:

www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/open-studio-tickets-718529951427