London’s socio-political modernism through photography

Two exhibitions in London speak to each other across the decades. At the Royal Institute of British Architects a study of late-1960s photography presents a balanced view of post-war planning and design, while south of the river, the Gareth Gardner Gallery offers a contemporary counterpoint with six photographers looking at a nearby estate and it’s residents. Veronica Simpson visited both.

It’s

funny how you can go five decades without any reference to the Architectural

Review’s groundbreaking 1969-70 series of photojournalistic Manplan issues – and then two exhibitions come along at once. Named Manplan because of its focus on the human, the series was a visually pioneering

exploration by leading photographers of the day of the social impacts and

aspects of architecture. The Royal Institute of British Architects [RIBA] has

delved into its archives to offer up both published and unpublished photographs

commissioned by the magazine, each image exploring a particular theme, from

failing transport and infrastructure, to the challenges of unloved and unlovely

modern housing.

Meanwhile, south of the Thames and packed tightly into photographer Gareth Gardner’s intimate gallery is an update of one of the housing projects photographed by Tony Ray-Jones for a Manplan issue on housing: the Pepys Estate. Gardner has composed responses to Ray-Jones’ work from four contemporary photographers (including himself), all of whom have long knowledge of and interest in the estate’s architecture and occupants, which can be found just around the corner from his Deptford gallery. The artist’s deep knowledge is clear in all of the photos, and especially in the tender and thoughtful film by James Price and Dr Tim Livsey, which observe its atmospheres through the seasons and years accompanied by residents’ recollections. The whole exhibition feels like an immersive dive into one distinctive space, across time.

![]()

![]()

When they first published the Manplan series, the Architectural Review dispersed their photographers across the whole of the UK, capturing a particular mood over an eight month period when post-war optimism had given way to frustration and pessimism around many of the big, mid-century experiments across planning, healthcare, mass housing, jobs, and transport. With one photographer per issue, the resulting grainy, black-and white images filled each magazine, almost entirely free of text.

While we can appreciate that this approach was groundbreaking in both its graphic and layout treatments, it’s somewhat depressing that those topics that were so urgent in 1969 are still high on the list of social ills: poorly designed schools, an overburdened healthcare system, neglected communities, inadequate housing, and inconsiderate planning. If the aim was to “provoke the magazine’s readers into thinking differently about the built environment,” as one wall caption states, it clearly didn’t work.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The first Manplan was themed Frustration. Patrick Ward took his camera on the road to explore issues of neglect and underinvestment. Wonderfully atmospheric shots resulted: the view through a grimy Victorian school window onto a bleak, rain-soaked schoolyard; a row of postwar houses completely dwarfed by the office blocks looming over them (hello Croydon!); the damp, shabby back office of an East London church where a woman and her child are waiting for welfare handouts.

Issue 2, Society in its Contacts invited Magnum photographer Ian Berry to show us the flaws and foibles in our transport and communications infrastructure. He gives us commuters pressed up against the doors of a train; and an amusing shot of a roofer up on top of York Minster, communicating via a huge walkie-talkie radio – no doubt cutting edge communications at the time. The successes of modernity were also part of the brief for these photographers, but it’s interesting that Preston Bus Garage, still a beacon of modernist transport design, appears later in Peter Barstow’s photo-essay on citizen participation in Manplan 7.

Manplan 3 looks at industry and its impact on the environment, guest editor Norman Foster working with images from photographer Tim Street-Porter. A wall caption tells us that the Manplan editors “believed in a ‘town workshop’ concept, where clean, small-scale industries would coexist with other human activities.” The aim was to re-integrate work, home, and leisure to make “cities more harmonious places to live and work in.” Personally, I’m not sure Sir Norman’s work over the last five decades would indicate any adherence to those values.

Street-Porter delivered a priceless photo of workers cottages dwarfed by belching industrial chimneys, its dehumanizing tableau uplifted by a bunch of tow-headed, scruffy but otherwise perfectly healthy-looking children posing for the camera, along a boundary wall. Elsewhere, a solitary dog walker is the only figure in a vast space of weed-strewn tarmac, fringed by barracks-like multi-story flats with slender industrial chimneys looming in the background, like pipelines from hell.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Manplan 4’s focus on community placed Tom Smith behind the lens. He put schools in the spotlight, exploring the idea that they should be multi-functional spaces for use by the whole neighbourhood – children in the day, parents and other adults after hours. I particularly liked his photo of trees reflected in a huge window looking into a spacious classroom in Leicestershire; one of Leicester County Council Architecture Department’s more admirable modernist examples, presumably. I am struck here by the revelation that a notion I thought was new when architects began (re)presenting it in the last two decades was in fact fifty years old.

The same is true of Manplan 6, Health and welfare, with the rallying cry for a more “human scale” approach to hospitals and housing. In Ian Berry’s photo of two NHS nurses, what strikes me is how well dressed they appear, in their immaculate uniforms – not to mention well, looked after, as they survey the gleaming tea urns and piled-high platters of food in the staff canteen.

Manplan 7, on citizen participation, handed the camera to Peter Balstow, who selects the good, the bad and the ugly of 1960s constructions: the caption to a dramatic, geometric shot of Leeds International swimming pool tells us how well loved the facility was, in contrast with the modernist monument of Newcastle Civic Centre, also pictured here, regarded as a local authority extravagance given how poorly Newcastle’s citizens were being housed in shoddily-built high rises.

![]()

![]()

The photography baton in Manplan 8 on Housing was handed, as mentioned above, to a young Tony Ray-Jones. What his photos seem to articulate most is the vivid communities housed in these grey, concrete, and tarmac landscapes. In a rare, people-less shot Ray-Jones frames a fragment of a terrace – two empty houses, huddled together, amidst the rubble of their newly demolished neighbours, framed by bland multi-storey blocks on either side.

The unflinching gaze and monochrome presentation of the Manplan series was controversial at the time, even if architectural historian Stephen Parnell called it: “the bravest moment in architectural publishing.” Its complete opposition to more-common photographic approach – all sharp-focused glamour shots of sculptural, empty buildings, taken on large format cameras against clear blue skies. But it had little impact on modern architecture journalism: glossy, utopian images of crisply contemporary buildings still prevail for both professional and consumer media, albeit now thoroughly yoked to the cause of digital, extractive capitalism/lifestyle porn. Magazines very rarely commission their own photography, so it’s left to architects to commission their own – and of course, their natural impulse would be to ask photographers to depict the work looking its best.

One criticism I have of this otherwise excellent and well-intentioned show is how small and dark the images seem, against its largely black backdrop. Possibly there was neither budget nor space to allow us to see these iconic shots on a larger scale. When they are scaled up, it makes a huge difference: the artistry, skill, and precision is clear in shots such as Patrick Ward’s South London political rally (intended for use in Manplan 9) and also one of Ray-Jones’ Pepys Estate shoot: a moment two boys, standing in a concrete flower pot (devoid of flowers), act out a cowboy drama, their explosive, animated forms vivid against the surrounding uniformity.

![]()

![]()

It was hoped the series might encourage a more socially-conscious, people-centred practice. Perhaps some in the 1970s took that idea and ran with it, but what happened to those good intentions over the ensuing decades? It has only recently come back into fashion, with established firms increasingly foregrounding their people skills. While younger practices are usually more proactive on this front, sometimes admirably so, you might think from the ensuing media rhetoric that participatory design is brand new.

At the end of the exhibition, a space is reserved for a noticeboard, inviting visitors’ propositions for hypothetical future Manplan editions. I like the fulsome responses it has attracted.

To discover what actually happened after Manplan ended you should head to Deptford, to see Boundary Conditions, at Gareth Gardner Gallery, utilising film, photography, graphics, and multimedia responses inspired by Ray-Jones’s work. I particularly liked Jérôme Favre’s big, colourful prints majoring on the grid-like form of high rises, photographed at twilight, ablaze with artificial light; Gardner’s 360 degree rotation around the block to show it from all angles; and Freddie Miller’s dive into the estate’s drill music scene. The exhibition also includes works by Tim George and Danilo Murru, while copies of the original Manplan issues are displayed alongside archive works about the Pepys Estate and the film by Price and Livsey.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Through words and images, Boundary Conditions beautifully reveals how social, political, and cultural contexts have played out against the architecture over the decades. Initially homes on this ambitious scheme were highly sought after, with Lewisham Council offering them first to their more affluent, professional tenants.

They became symptomatic of an alarming degree of racial segregation in the area, with newly-arrived migrants from Africa and the Caribbean silo-ed away from the development. But when greater integration finally came, it was accompanied by poor maintenance and poverty – never a recipe for harmony.

What Boundary Conditions tackles is the impacts of gentrification – that uniquely 21st century affliction. Murru’s series No Ball Games hits the sweet spot here, revealing the estate’s social and physical borders, flagging up the uneasy visual and social adjacencies of Convoys Wharf and Deptford Landings.

Each show is well worth visiting, but it’s rare that two shows in London work in such perfect dialogue with each other on still-important issues. Visit both shows to not only consider the historical photographic gaze upon architecture’s socio-political concerns, but also those of our current climate.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Meanwhile, south of the Thames and packed tightly into photographer Gareth Gardner’s intimate gallery is an update of one of the housing projects photographed by Tony Ray-Jones for a Manplan issue on housing: the Pepys Estate. Gardner has composed responses to Ray-Jones’ work from four contemporary photographers (including himself), all of whom have long knowledge of and interest in the estate’s architecture and occupants, which can be found just around the corner from his Deptford gallery. The artist’s deep knowledge is clear in all of the photos, and especially in the tender and thoughtful film by James Price and Dr Tim Livsey, which observe its atmospheres through the seasons and years accompanied by residents’ recollections. The whole exhibition feels like an immersive dive into one distinctive space, across time.

Figs.i,ii

When they first published the Manplan series, the Architectural Review dispersed their photographers across the whole of the UK, capturing a particular mood over an eight month period when post-war optimism had given way to frustration and pessimism around many of the big, mid-century experiments across planning, healthcare, mass housing, jobs, and transport. With one photographer per issue, the resulting grainy, black-and white images filled each magazine, almost entirely free of text.

While we can appreciate that this approach was groundbreaking in both its graphic and layout treatments, it’s somewhat depressing that those topics that were so urgent in 1969 are still high on the list of social ills: poorly designed schools, an overburdened healthcare system, neglected communities, inadequate housing, and inconsiderate planning. If the aim was to “provoke the magazine’s readers into thinking differently about the built environment,” as one wall caption states, it clearly didn’t work.

Figs.iii-v

The first Manplan was themed Frustration. Patrick Ward took his camera on the road to explore issues of neglect and underinvestment. Wonderfully atmospheric shots resulted: the view through a grimy Victorian school window onto a bleak, rain-soaked schoolyard; a row of postwar houses completely dwarfed by the office blocks looming over them (hello Croydon!); the damp, shabby back office of an East London church where a woman and her child are waiting for welfare handouts.

Issue 2, Society in its Contacts invited Magnum photographer Ian Berry to show us the flaws and foibles in our transport and communications infrastructure. He gives us commuters pressed up against the doors of a train; and an amusing shot of a roofer up on top of York Minster, communicating via a huge walkie-talkie radio – no doubt cutting edge communications at the time. The successes of modernity were also part of the brief for these photographers, but it’s interesting that Preston Bus Garage, still a beacon of modernist transport design, appears later in Peter Barstow’s photo-essay on citizen participation in Manplan 7.

Manplan 3 looks at industry and its impact on the environment, guest editor Norman Foster working with images from photographer Tim Street-Porter. A wall caption tells us that the Manplan editors “believed in a ‘town workshop’ concept, where clean, small-scale industries would coexist with other human activities.” The aim was to re-integrate work, home, and leisure to make “cities more harmonious places to live and work in.” Personally, I’m not sure Sir Norman’s work over the last five decades would indicate any adherence to those values.

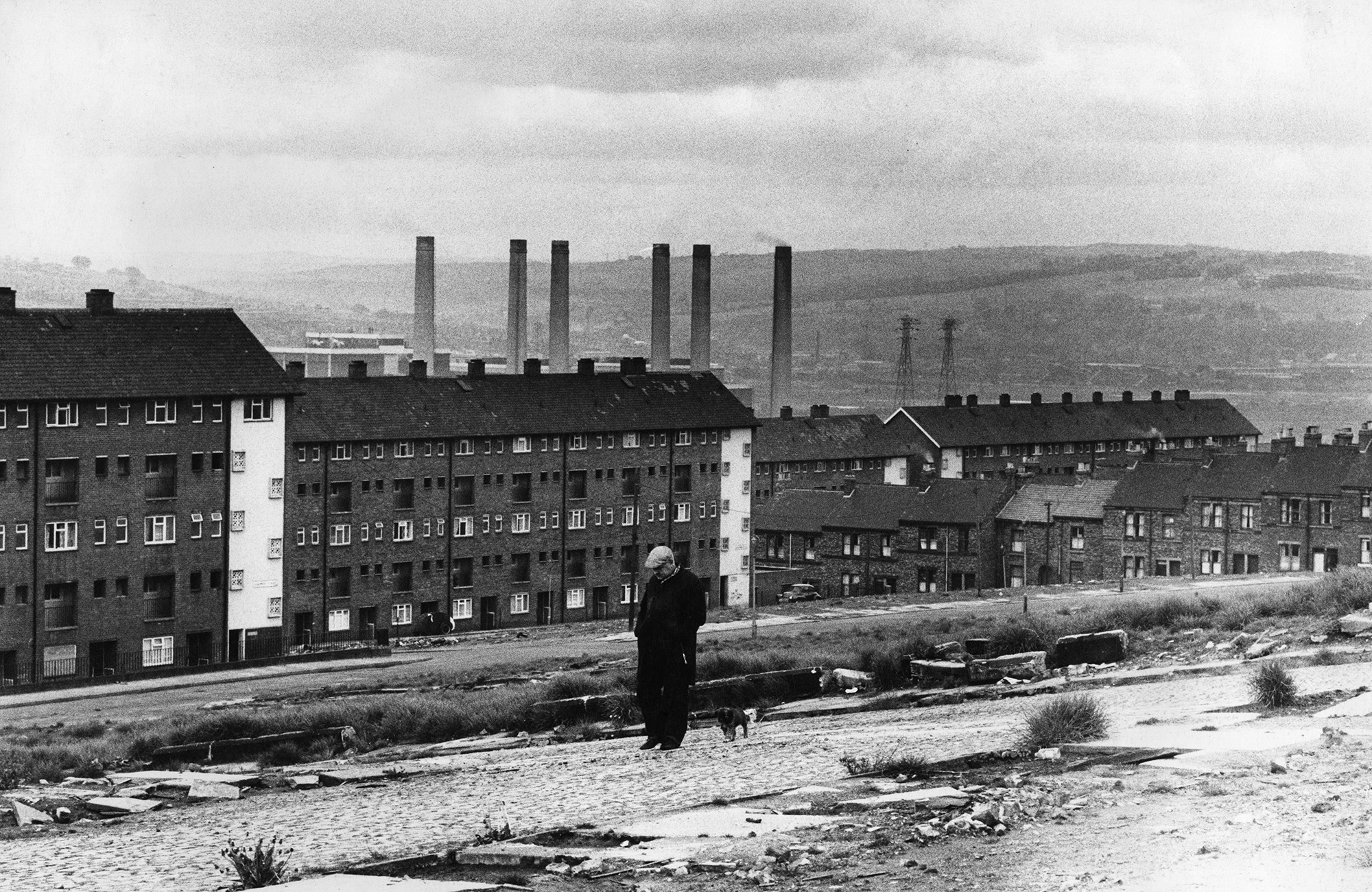

Street-Porter delivered a priceless photo of workers cottages dwarfed by belching industrial chimneys, its dehumanizing tableau uplifted by a bunch of tow-headed, scruffy but otherwise perfectly healthy-looking children posing for the camera, along a boundary wall. Elsewhere, a solitary dog walker is the only figure in a vast space of weed-strewn tarmac, fringed by barracks-like multi-story flats with slender industrial chimneys looming in the background, like pipelines from hell.

Figs.vi-viii

Manplan 4’s focus on community placed Tom Smith behind the lens. He put schools in the spotlight, exploring the idea that they should be multi-functional spaces for use by the whole neighbourhood – children in the day, parents and other adults after hours. I particularly liked his photo of trees reflected in a huge window looking into a spacious classroom in Leicestershire; one of Leicester County Council Architecture Department’s more admirable modernist examples, presumably. I am struck here by the revelation that a notion I thought was new when architects began (re)presenting it in the last two decades was in fact fifty years old.

The same is true of Manplan 6, Health and welfare, with the rallying cry for a more “human scale” approach to hospitals and housing. In Ian Berry’s photo of two NHS nurses, what strikes me is how well dressed they appear, in their immaculate uniforms – not to mention well, looked after, as they survey the gleaming tea urns and piled-high platters of food in the staff canteen.

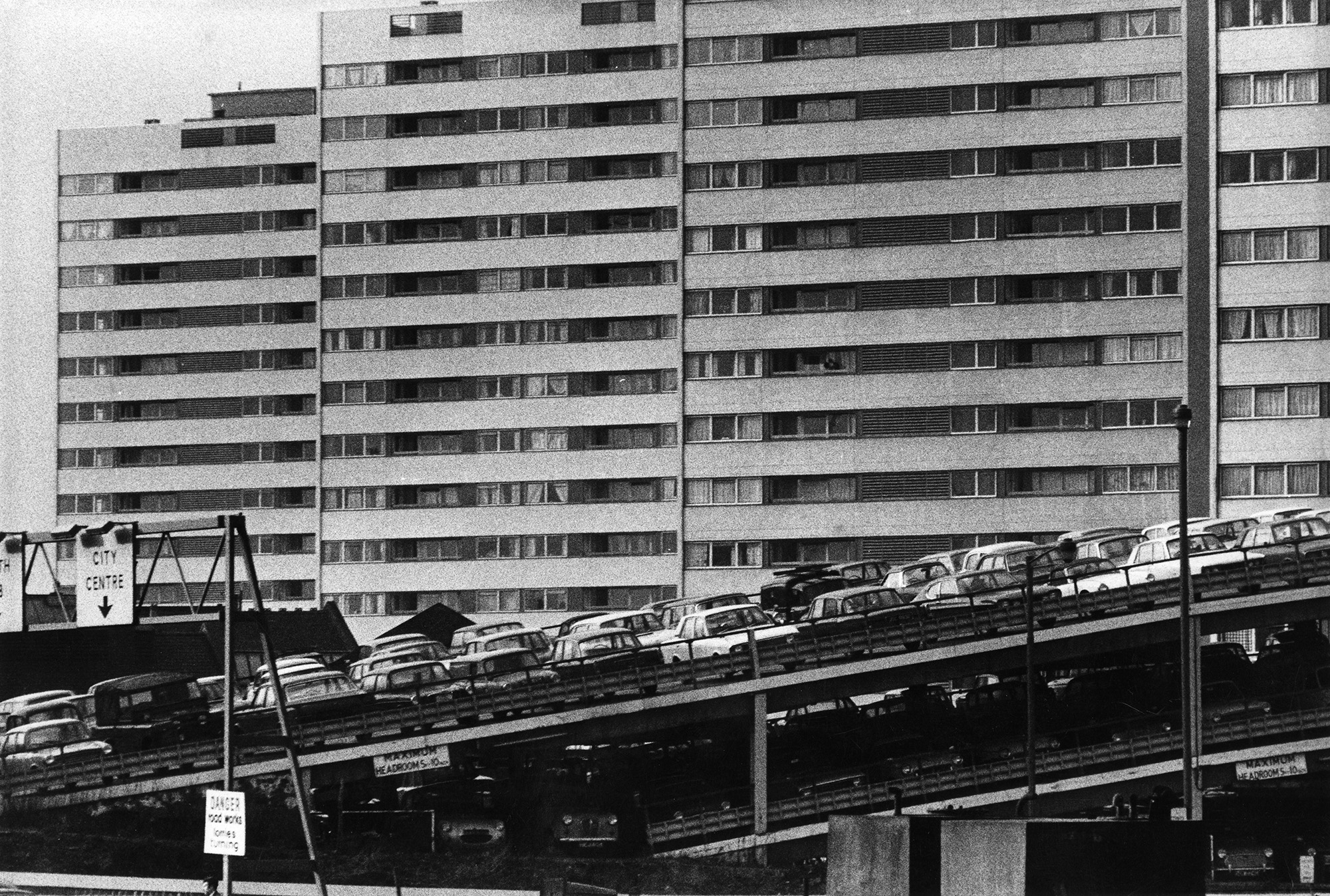

Manplan 7, on citizen participation, handed the camera to Peter Balstow, who selects the good, the bad and the ugly of 1960s constructions: the caption to a dramatic, geometric shot of Leeds International swimming pool tells us how well loved the facility was, in contrast with the modernist monument of Newcastle Civic Centre, also pictured here, regarded as a local authority extravagance given how poorly Newcastle’s citizens were being housed in shoddily-built high rises.

Figs.ix,x

The photography baton in Manplan 8 on Housing was handed, as mentioned above, to a young Tony Ray-Jones. What his photos seem to articulate most is the vivid communities housed in these grey, concrete, and tarmac landscapes. In a rare, people-less shot Ray-Jones frames a fragment of a terrace – two empty houses, huddled together, amidst the rubble of their newly demolished neighbours, framed by bland multi-storey blocks on either side.

The unflinching gaze and monochrome presentation of the Manplan series was controversial at the time, even if architectural historian Stephen Parnell called it: “the bravest moment in architectural publishing.” Its complete opposition to more-common photographic approach – all sharp-focused glamour shots of sculptural, empty buildings, taken on large format cameras against clear blue skies. But it had little impact on modern architecture journalism: glossy, utopian images of crisply contemporary buildings still prevail for both professional and consumer media, albeit now thoroughly yoked to the cause of digital, extractive capitalism/lifestyle porn. Magazines very rarely commission their own photography, so it’s left to architects to commission their own – and of course, their natural impulse would be to ask photographers to depict the work looking its best.

One criticism I have of this otherwise excellent and well-intentioned show is how small and dark the images seem, against its largely black backdrop. Possibly there was neither budget nor space to allow us to see these iconic shots on a larger scale. When they are scaled up, it makes a huge difference: the artistry, skill, and precision is clear in shots such as Patrick Ward’s South London political rally (intended for use in Manplan 9) and also one of Ray-Jones’ Pepys Estate shoot: a moment two boys, standing in a concrete flower pot (devoid of flowers), act out a cowboy drama, their explosive, animated forms vivid against the surrounding uniformity.

Figs.xi,xii

It was hoped the series might encourage a more socially-conscious, people-centred practice. Perhaps some in the 1970s took that idea and ran with it, but what happened to those good intentions over the ensuing decades? It has only recently come back into fashion, with established firms increasingly foregrounding their people skills. While younger practices are usually more proactive on this front, sometimes admirably so, you might think from the ensuing media rhetoric that participatory design is brand new.

At the end of the exhibition, a space is reserved for a noticeboard, inviting visitors’ propositions for hypothetical future Manplan editions. I like the fulsome responses it has attracted.

To discover what actually happened after Manplan ended you should head to Deptford, to see Boundary Conditions, at Gareth Gardner Gallery, utilising film, photography, graphics, and multimedia responses inspired by Ray-Jones’s work. I particularly liked Jérôme Favre’s big, colourful prints majoring on the grid-like form of high rises, photographed at twilight, ablaze with artificial light; Gardner’s 360 degree rotation around the block to show it from all angles; and Freddie Miller’s dive into the estate’s drill music scene. The exhibition also includes works by Tim George and Danilo Murru, while copies of the original Manplan issues are displayed alongside archive works about the Pepys Estate and the film by Price and Livsey.

Figs.xiii-xv

Through words and images, Boundary Conditions beautifully reveals how social, political, and cultural contexts have played out against the architecture over the decades. Initially homes on this ambitious scheme were highly sought after, with Lewisham Council offering them first to their more affluent, professional tenants.

They became symptomatic of an alarming degree of racial segregation in the area, with newly-arrived migrants from Africa and the Caribbean silo-ed away from the development. But when greater integration finally came, it was accompanied by poor maintenance and poverty – never a recipe for harmony.

What Boundary Conditions tackles is the impacts of gentrification – that uniquely 21st century affliction. Murru’s series No Ball Games hits the sweet spot here, revealing the estate’s social and physical borders, flagging up the uneasy visual and social adjacencies of Convoys Wharf and Deptford Landings.

Each show is well worth visiting, but it’s rare that two shows in London work in such perfect dialogue with each other on still-important issues. Visit both shows to not only consider the historical photographic gaze upon architecture’s socio-political concerns, but also those of our current climate.

Figs.xvi-xviii

Veronica Simpson has spent the last three decades observing the most interesting evolutions in design, architecture & art, for both consumer & specialist magazines, including Sunday Times Style, Blueprint, Damn and Studio International. Informed by an MSc in Environmental Psychology (2009-10, University of Surrey), her writing aims to place these creative disciplines in context as they relate to human needs or changing social & cultural values. With the current planetary & economic crises in mind, her writings prioritise the artists, designers & architects whose work best articulates the critical issues & ideally offers enlightened responses.

visit

Wide-Angle View: architecture as social space in the Manplan series 1969-1970 is exhibited at the Royal Institute of British Architects, London, until 24 February 2024. More details available at: ww.architecture.com/explore-architecture/exhibitions/Manplan-Wide-angle-view

Boundary Conditions: Reframing the Pepys Estate is exhibited at Gareth Gardner Gallery, London, until 15 October 2023. More detrails available at: www.garethgardner.com/blog/boundary-conditions-reframing-the-pepys-estate

images

figs.i,iii,vii Wide-Angle View: architecture as social space in the Manplan series 1969-1970, installation views. Photographs © Agnese Sanvito.

figs.ii,xvi From the series No Ball Games by

Danilo Murru.

Photograph ©

Danilo Murru.

fig.iv

Lillington Gardens Estate, Pimlico, London, Architects: Darbourne & Darke. Photograph

©

Tony Ray-Jones. Courtesy Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections.

fig.v

Classroom window, Wales.

Unknown photographer. Courtesy Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections.

fig.vi

Workers' housing and industrial cooling towers, Teesside.

Photograph ©

Tim Street-Porter. Courtesy Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections.

fig.viii

Workers' housing, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, with Dunston Power Station behind. Photograph © Tim Street-Porter. Courtesy Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections.

fig.ix

Coppice County Junior School, Sutton Coldfield, West Midlands

Architects: Warwickshire CC Architects Dept.

Photograph © Tim Street-Porter. Courtesy Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections.

fig.x

High-rise flats and multi-storey car park, Birmingham.

Photograph ©

Peter Baistow. Courtesy Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections.

fig.xi Low-rise linear housing, Tavy Bridge, Thamesmead, Greenwich, London.

Architects: Greater London Council Department of Architecture & Civic Design.

Photograph © Tony Ray-Jones. Courtesy Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections.

fig.xii

Southmere Lake and Southmere Towers, Thamesmead, Greenwich, London.

Architects: Greater London Council Department of Architecture & Civic Design. Photograph © Tony Ray-Jones. Courtesy Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections.

figs.xiii,xv,xviii From the series Scissors by Gareth

Gardner,

Photograph ©

Gareth Gardner.

figs.xiv,xvii From the series The District by

Freddie Miller.

Photograph ©

Freddie Miller.

publication date

28 September 2023

tags

Architectural Review, Peter Barstow, Ian Berry, Croydon, Deptford, Norman Foster, Gareth Gardner, Gareth Gardner Gallery, Tim George, Healthcare, Housing, Immigration, Lewisham, Tim Livsey, London, Manplan, Freddie Miller, Modernism, Danilo Murru, Newcastle, Stephen Parnell, Pepys Estate, Photography, Photojournalism, Planning, Preston bus garage, James Price, Tony Ray-Jones, RIBA, Schools, Veronica Simpson, Tom Smith, Socio-political, Tim Street-Porter, Patrick Ward

Boundary Conditions: Reframing the Pepys Estate is exhibited at Gareth Gardner Gallery, London, until 15 October 2023. More detrails available at: www.garethgardner.com/blog/boundary-conditions-reframing-the-pepys-estate