Edinburgh Art Festival: a creative journey through the city’s buildings

Edinburgh Art Festival spreads itself across a city already packed with culture & people over August. Will Jennings visited, finding the festival a perfect way to not only discover a lot of excellent contemporary art, but also a great excuse to explore the city’s built history.

“Are you up here for

the festival?” It becomes a standard question asked to anybody evidently an

out-of-towner visiting Edinburgh in August. By the Festival, singular,

they invariably mean the world-famous International Festival and associated

Fringe Festival, which take over the city’s streets and buildings. But, there

is also the city’s Film Festival, International Book Festival, TV Festival, Mela,

Military Tattoo, and the Art Festival – and it’s the last that we focus on here.

Visual art had always been a component of the main International Festival, but since 1966 had been managed outside of the main programme, and since 2004 has formed its own separate festival running concurrently.

Edinburgh is busy over August. It can be a slow city to navigate, with visitors queuing up to access the many side-alleys and the ease of getting sucked into a street busker’s audience. So, it can be helpful to have a strategy rather than a casual amble. Here, we select highlights from this years Art Festival – which runs through to 27 August, though most featured exhibitions run on later into the year – which are excellent projects located in some of the Festival’s more interesting architectural locations.

Visit the Edinburgh Art Festival website to find out more: www.edinburghartfestival.com

Visual art had always been a component of the main International Festival, but since 1966 had been managed outside of the main programme, and since 2004 has formed its own separate festival running concurrently.

Edinburgh is busy over August. It can be a slow city to navigate, with visitors queuing up to access the many side-alleys and the ease of getting sucked into a street busker’s audience. So, it can be helpful to have a strategy rather than a casual amble. Here, we select highlights from this years Art Festival – which runs through to 27 August, though most featured exhibitions run on later into the year – which are excellent projects located in some of the Festival’s more interesting architectural locations.

Visit the Edinburgh Art Festival website to find out more: www.edinburghartfestival.com

figs.i,ii: Haven for Artists, photography by Sally Jubb

figs.iii,iv: from Sean Burns, Dorothy Towers,Courtesy & © Sean Burns

FRENCH INSTITUTE

Haven for Artists

Sean Burns

Designed by architect James Mcintyre Henry, and built between 1899 and 1904 as the Midlothian County buildings, but has since 2017 been the base for the French Institute and consul. It is, however, artists from a nation formerly under French mandate who have made the ground floor their home for the Festival.

Haven for Artists (HFA) is a cultural feminist organisation based in Beirut, Lebanon. They work at the intersection of art and activism, and as a physical and digital platform supporting cultural works and knowledge production rooted in intersectional feminism, gender and racial justice, and decolonial practices. For Edinburgh Art Festival they have taken up residency in created a welcoming living room for anybody to enter and take a break from the crowds outside on the Royal Mile. Here, visitors can flick through the zine they produce to platform emerging voices and progressive politics through culture, ideas which are also being embedded locally across the festival through events, conversations, and activities with local arts and campaigning organisations.

Upstairs in the grand, civic building is a presentation from artist and writer Sean Burns. His film, Dorothy Towers, explores the history and residents of a pair of twin social housing blocks in central Birmingham which became central to the city’s gay community. Completed in 1971, Clydesdale and Cleveland Towers were in proximity to the Gay Village, and while the properties were evidently not the most salubrious or well-managed, they became a safe and secure home to queer residents over a period of homophobia and AIDS. In the film we visit apartments from residents, who describe not only the towers themselves but the changing face and urbanism of Birmingham, and how that intersects with community, culture, and kinship.

Haven for Artists

Sean Burns

Designed by architect James Mcintyre Henry, and built between 1899 and 1904 as the Midlothian County buildings, but has since 2017 been the base for the French Institute and consul. It is, however, artists from a nation formerly under French mandate who have made the ground floor their home for the Festival.

Haven for Artists (HFA) is a cultural feminist organisation based in Beirut, Lebanon. They work at the intersection of art and activism, and as a physical and digital platform supporting cultural works and knowledge production rooted in intersectional feminism, gender and racial justice, and decolonial practices. For Edinburgh Art Festival they have taken up residency in created a welcoming living room for anybody to enter and take a break from the crowds outside on the Royal Mile. Here, visitors can flick through the zine they produce to platform emerging voices and progressive politics through culture, ideas which are also being embedded locally across the festival through events, conversations, and activities with local arts and campaigning organisations.

Upstairs in the grand, civic building is a presentation from artist and writer Sean Burns. His film, Dorothy Towers, explores the history and residents of a pair of twin social housing blocks in central Birmingham which became central to the city’s gay community. Completed in 1971, Clydesdale and Cleveland Towers were in proximity to the Gay Village, and while the properties were evidently not the most salubrious or well-managed, they became a safe and secure home to queer residents over a period of homophobia and AIDS. In the film we visit apartments from residents, who describe not only the towers themselves but the changing face and urbanism of Birmingham, and how that intersects with community, culture, and kinship.

STILLS:

CENTRE FOR PHOTOGRAPHY

Markéta

Luskačová

Established in 1977, Stills is now regarded as a leading authority on photography. For many years it has benefited from its location in the heart of the city’s Old Town, sitting as it does in the middle of the sloping and steep Cockburn Street. This central location is both a blessing and a curse. The huge footfall of passing visitors means many step inside who may not normally enter a photography gallery, but it also has recently resulted in a huge increase in rents, which trebled between 2014 and 2019.

An excellent shop in the entrance helps raise monies to continue the charity and pay the council an exorbitant rent, and those who delve deeper into the gallery will currently discover an excellent hang of the long archive of Prague-born, UK-based photographer Markéta Luskačová. Luskačová has been capturing communities, culture, and place since the 1970s and since the 90s has been building a rich body of work focusing on childhood, from which this curation is drawn.

There is much of architectural interest within the captured scenes, not least images of London’s markets and schools over the 1980s. The display is loosely chronological, but without captions or dates invites the reader to draw their own connections and meanings from images on show, creating a sense of childhood beyond borders and systems.

Established in 1977, Stills is now regarded as a leading authority on photography. For many years it has benefited from its location in the heart of the city’s Old Town, sitting as it does in the middle of the sloping and steep Cockburn Street. This central location is both a blessing and a curse. The huge footfall of passing visitors means many step inside who may not normally enter a photography gallery, but it also has recently resulted in a huge increase in rents, which trebled between 2014 and 2019.

An excellent shop in the entrance helps raise monies to continue the charity and pay the council an exorbitant rent, and those who delve deeper into the gallery will currently discover an excellent hang of the long archive of Prague-born, UK-based photographer Markéta Luskačová. Luskačová has been capturing communities, culture, and place since the 1970s and since the 90s has been building a rich body of work focusing on childhood, from which this curation is drawn.

There is much of architectural interest within the captured scenes, not least images of London’s markets and schools over the 1980s. The display is loosely chronological, but without captions or dates invites the reader to draw their own connections and meanings from images on show, creating a sense of childhood beyond borders and systems.

fig.v: Carnival procession, Roztoky, Czech Republic (2008) © Markéta Luskačová

fig.vi: Two boys with their jumpers over their heads, Booker Avenue primary school, Liverpool (1988) © Markéta Luskačová

www.stills.org

fig. vii: Platform installation view, photograph by Sally Jubb

figs. viii-x:

Platform installation view, photographs by Will Jennings

www.edinburghartfestival.com/platform23

www.aqsaarif.com

www.crystalbennes.com

www.rudykanhye.co.uk

www.richardmaguire.net

TRINITY

APSE

Platform: Aqsa Arif, Crystal Bennes, Rudy Kanhye & Richard Maguire

In its 9th edition, Platform Early Career Artist Award presents an annual display of the shortlisted entrants. This year it is displayed under the remarkable vaulted ceilings of Trinity Apse, a 15th century gothic chapel secreted in the centre of the city. The building was originally in the Waverley Valley, the part of the city now full of trainlines running into the main station, and in the 1800s was deconstructed brick-by-brick and rebuilt in its current location in the Old Town – albeit with a slight redesign after various parts of the building were pilfered in transit.

It makes for an atmospheric setting to show the works of these four emerging artists. Central to the display are hanging sheets from Crystal Bennes, an artist with a long-held interest in architecture and landscape. The work here considers imperial control of Irish land through the systematic migration of English women to Ireland, an Imperial system of control by which the English sought to transfer their power, language, and customs through forced marriage.

Aqsa Arif’s work has overlapping themes, their multi-media installation considers the Tawaid, a Mughal era entertainer and courtesan once highly regarded before control and subjugation at the hands of the British Empire. The film is enclosed behind a delightful architectural façade based on the Jeeramadi, once the centre of Tawaif culture and now Lahore’s red-light district.

Richard Maguire’s work is derived from research on Anglo-Indian intimacies over colonisation, with Rudy Kanhye using the colours of the Mauritius flag in their work trying to reappropriate stolen physical and metaphysical spaces as an act of decolonisation.

Platform: Aqsa Arif, Crystal Bennes, Rudy Kanhye & Richard Maguire

In its 9th edition, Platform Early Career Artist Award presents an annual display of the shortlisted entrants. This year it is displayed under the remarkable vaulted ceilings of Trinity Apse, a 15th century gothic chapel secreted in the centre of the city. The building was originally in the Waverley Valley, the part of the city now full of trainlines running into the main station, and in the 1800s was deconstructed brick-by-brick and rebuilt in its current location in the Old Town – albeit with a slight redesign after various parts of the building were pilfered in transit.

It makes for an atmospheric setting to show the works of these four emerging artists. Central to the display are hanging sheets from Crystal Bennes, an artist with a long-held interest in architecture and landscape. The work here considers imperial control of Irish land through the systematic migration of English women to Ireland, an Imperial system of control by which the English sought to transfer their power, language, and customs through forced marriage.

Aqsa Arif’s work has overlapping themes, their multi-media installation considers the Tawaid, a Mughal era entertainer and courtesan once highly regarded before control and subjugation at the hands of the British Empire. The film is enclosed behind a delightful architectural façade based on the Jeeramadi, once the centre of Tawaif culture and now Lahore’s red-light district.

Richard Maguire’s work is derived from research on Anglo-Indian intimacies over colonisation, with Rudy Kanhye using the colours of the Mauritius flag in their work trying to reappropriate stolen physical and metaphysical spaces as an act of decolonisation.

TALBOT RICE

Lawrence Abu Hamdan

Jesse Jones

There is an intriguing double-bill at Talbot Rice gallery with two works which tackle immersive, physical spaces. In a grand neoclassical Georgian gallery, Lawrence Abu Hamdan presents 45th Parallel, a work previously exhibited at Spike Island in Bristol and written about in recessed.space last December (see 00069). The hang of theatre beckdrops works extremely well in the Edinburgh space, with the galleries above allowing vantage down into the display as well as an alternative position from which to watch the intriguing film of the Haskell Free Library and Opera House, which straddles the United States and Canadian border.

Also showing, in the contemporary space of the gallery, is Jesse Jones’ The Tower, an intriguing and compelling mix of video, installation, performance, and sculpture. A dark, depthless space is transformed by hanging curtains sensually subdividing it into a changing realm. Lights slowly draw focus from one element to another, including an anchorite concealed within a wall looking out, then passing symbolic tokens through to the observer.

The work explores stories and histories of women portrayed as saints or witches, looking for the mystic and magical present before the 16th century heresy trials across Europe. They offer glimpses of ecstatic visions and melancholy, of freedom and subjugation, and of a potential and otherness lost to political and social oppression.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan

Jesse Jones

There is an intriguing double-bill at Talbot Rice gallery with two works which tackle immersive, physical spaces. In a grand neoclassical Georgian gallery, Lawrence Abu Hamdan presents 45th Parallel, a work previously exhibited at Spike Island in Bristol and written about in recessed.space last December (see 00069). The hang of theatre beckdrops works extremely well in the Edinburgh space, with the galleries above allowing vantage down into the display as well as an alternative position from which to watch the intriguing film of the Haskell Free Library and Opera House, which straddles the United States and Canadian border.

Also showing, in the contemporary space of the gallery, is Jesse Jones’ The Tower, an intriguing and compelling mix of video, installation, performance, and sculpture. A dark, depthless space is transformed by hanging curtains sensually subdividing it into a changing realm. Lights slowly draw focus from one element to another, including an anchorite concealed within a wall looking out, then passing symbolic tokens through to the observer.

The work explores stories and histories of women portrayed as saints or witches, looking for the mystic and magical present before the 16th century heresy trials across Europe. They offer glimpses of ecstatic visions and melancholy, of freedom and subjugation, and of a potential and otherness lost to political and social oppression.

figs x,xi: Lawrence Abu Hamdan, 45th Parallel. Installation view at Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh, 2023.

Courtesy the artist and Talbot Rice Gallery.

Photo: Sally Jubb

figs. xii,xiii: Jesse Jones, The Tower.

Installation view Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh, 2023

Courtesy the artist and Talbot Rice Gallery.

Photo: Sally Jubb

www.trg.ed.ac.uk

www.lawrenceabuhamdan.com

www.jessejonesartist.com

figs. xiv-xvi: Installation view of Andrew Cranston: Never a joiner Ingleby, Edinburgh (17 June – 16 September 2023).

Photographs: John McKenzie

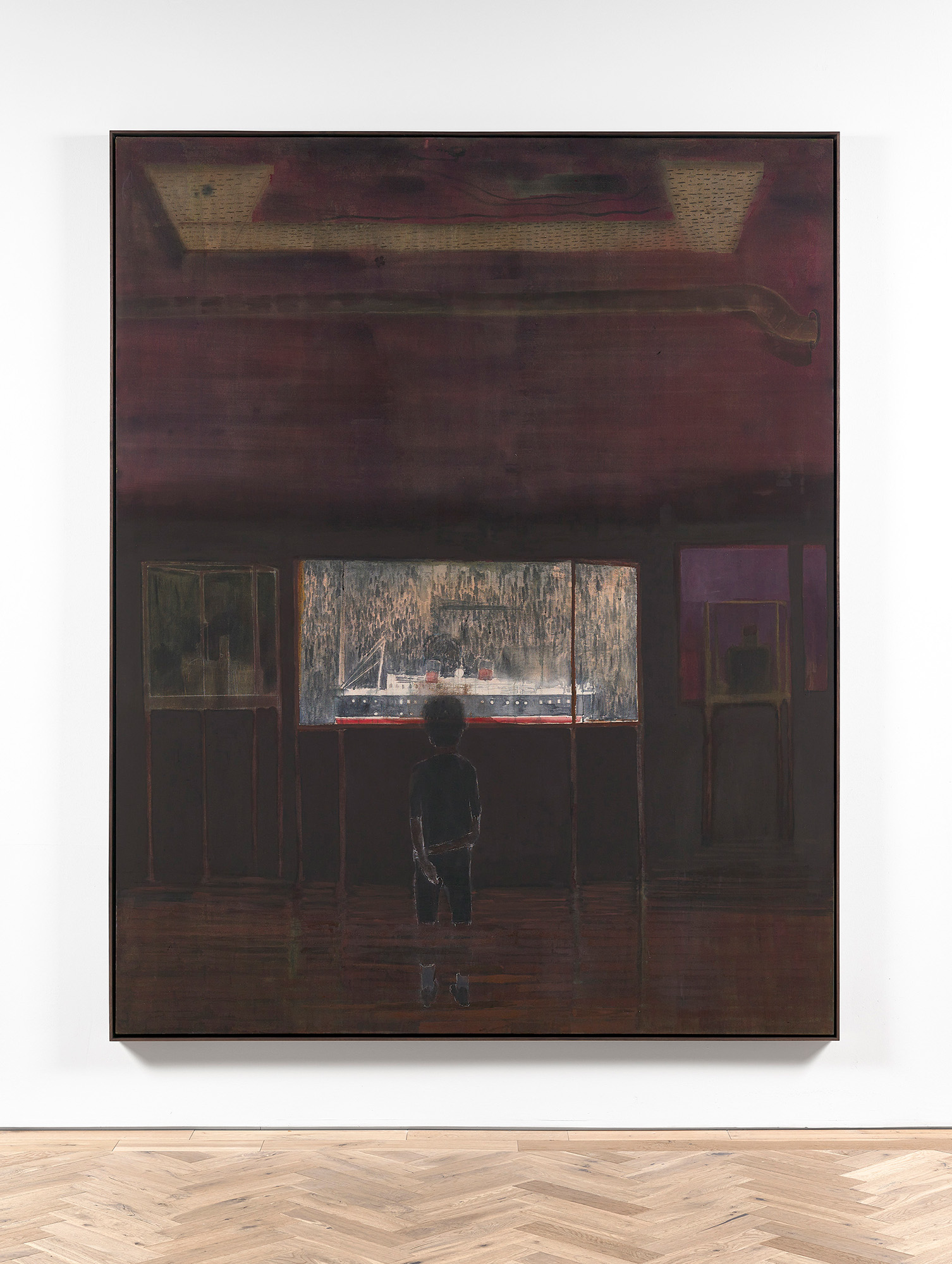

fig. xvii: Andrew Cranston,

Questions of travel (2023),

distemper and oil on canvas,

253.5 x 203.2 cm

99 3/4 x 80 in (framed).

Courtesy of the Artist and Ingleby, Edinburgh.

Photograph: John McKenzie

www.inglebygallery.com

www.inglebygallery.com/artists/32-andrew-cranston/overview

INGLEBY GALLERY

Andrew Cranston

What was once a meeting house for the Glasites – a small religious sect which broke from the Church of Scotland in 1732 – is now an art gallery resonant with light, history, and atmosphere. Alexander Black, the architect who designed the space in 1834, could never have imagined that the building would once become a space to stand back and take in contemporary arts, but it works perfectly for its new function.

Currently on display are paintings by Andrew Cranston, using a palette which works incredibly well with the wooden herringbone floor and tempered light coming through the octagonal ceiling light. Cranston’s canvases also sing with story, with unexplained characters and situations that invite narratives to be laid upon them. The ideas that unfold from his brush may come from a collection of memories or imaginaries, presented together to create an unreliable moment or potential future, laden with cinematic, art historical, and literature readings.

Andrew Cranston

What was once a meeting house for the Glasites – a small religious sect which broke from the Church of Scotland in 1732 – is now an art gallery resonant with light, history, and atmosphere. Alexander Black, the architect who designed the space in 1834, could never have imagined that the building would once become a space to stand back and take in contemporary arts, but it works perfectly for its new function.

Currently on display are paintings by Andrew Cranston, using a palette which works incredibly well with the wooden herringbone floor and tempered light coming through the octagonal ceiling light. Cranston’s canvases also sing with story, with unexplained characters and situations that invite narratives to be laid upon them. The ideas that unfold from his brush may come from a collection of memories or imaginaries, presented together to create an unreliable moment or potential future, laden with cinematic, art historical, and literature readings.

EDINBURGH SCULPTURE WORKSHOP

Sebastian Thomas

Adam Lewis Jacob & Ryosuke Kiyasu

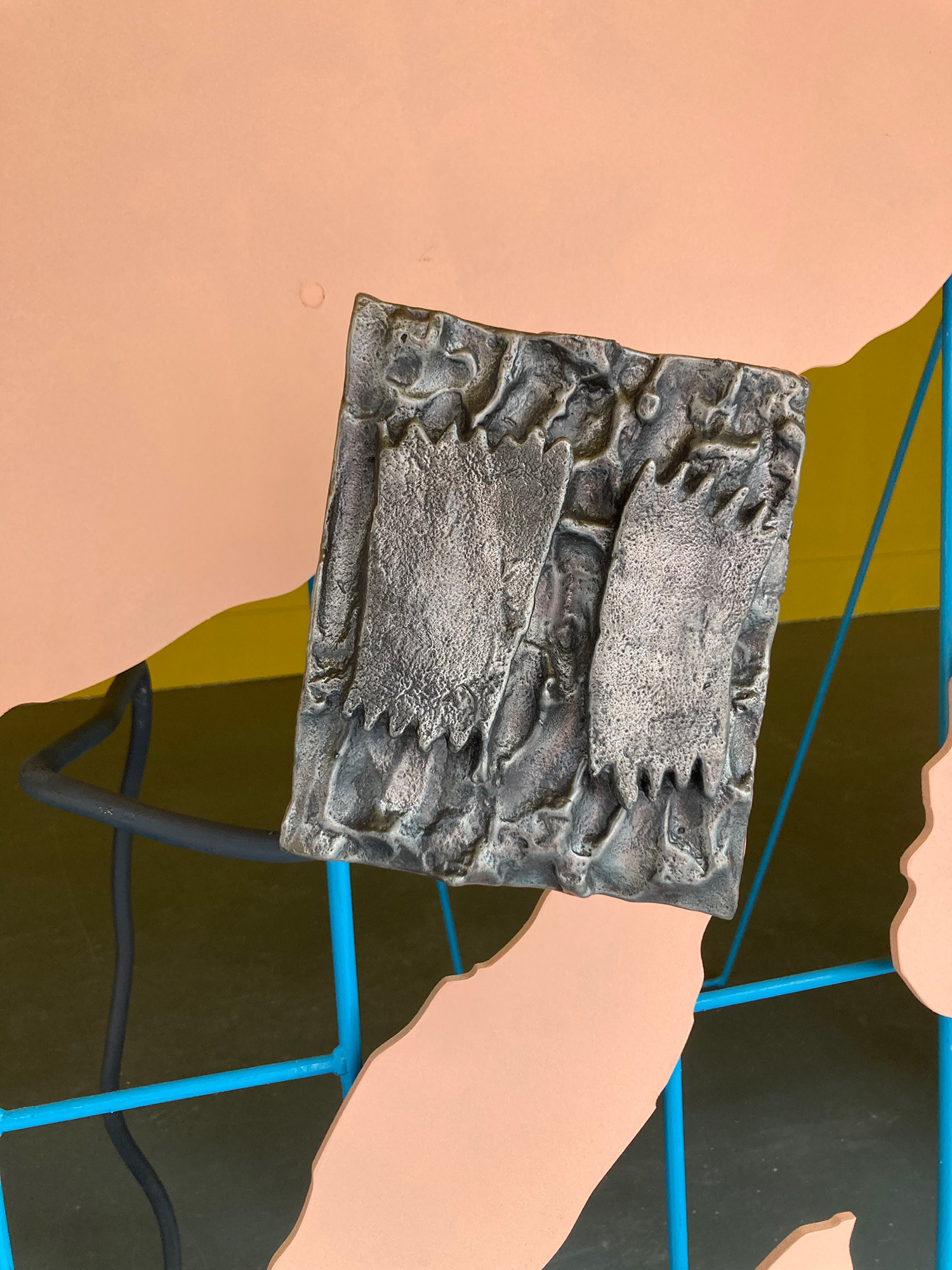

In a large campus in Leith, designed by Sutherland Hussey Harris Architects, Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop is primarily a space of making and creative material exploration. It is open to anybody curious about making sculpture, and the buildings which opened in phases from 2012 offer facilities which mean scale of ambition is not an issue.

The campus is designed porously, offering a café to the local community and steps into a working courtyard that can double up as events and activity space. A shallow window gallery directly faces the residential street, with A New Face in Hell, by Sebastian Thomas currently disturbing the peace with a framework golem of transformative materials and uneasy form.

Deeper into the complex, a film by Adam Lewis Jacob, made in collaboration with Japanese percussionist Ryosuke Kiyasu, offers a performance sculpture which flits between footage of Japanese urban scenes, painting onto 16mm film, and a recording of Kiyasu energetically performing. Altogether it’s a feverdream documentary of a compelling musician which compresses the work of the musician into a new artwork, as if in a frenetic, impulsive fight to see who owns an idea and how it’s received.

Sebastian Thomas

Adam Lewis Jacob & Ryosuke Kiyasu

In a large campus in Leith, designed by Sutherland Hussey Harris Architects, Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop is primarily a space of making and creative material exploration. It is open to anybody curious about making sculpture, and the buildings which opened in phases from 2012 offer facilities which mean scale of ambition is not an issue.

The campus is designed porously, offering a café to the local community and steps into a working courtyard that can double up as events and activity space. A shallow window gallery directly faces the residential street, with A New Face in Hell, by Sebastian Thomas currently disturbing the peace with a framework golem of transformative materials and uneasy form.

Deeper into the complex, a film by Adam Lewis Jacob, made in collaboration with Japanese percussionist Ryosuke Kiyasu, offers a performance sculpture which flits between footage of Japanese urban scenes, painting onto 16mm film, and a recording of Kiyasu energetically performing. Altogether it’s a feverdream documentary of a compelling musician which compresses the work of the musician into a new artwork, as if in a frenetic, impulsive fight to see who owns an idea and how it’s received.

figs. xiii,xix:

Sebastian

Thomas: A New Face In Hell.

Image

Credits: Oana Stanciu

fig. xx: Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop, Adam Lewis Jacob, Serious heat (Still). Courtesy the artist

fig. xxi: Adam Lewis Jacob, Tense, ESW-Installation.

Courtesy Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop.

fig. xxii: Adam Lewis Jacob, Tense, screened at Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop.

Courtesy Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop.

www.edinburghsculpture.org

www.sebastianthomas.co.uk

www.adamlewisjacob.com

www.kiyasu.com

fig. xxiii: View of Edinburgh Observatory from Nelson's Monument, Calton Hill, Edinburgh, UK. Photo taken by Alan Ford 2006-05-25. Creative Commons available here.

fig. xxiv,xxv: 1. I wear my wounds on my tongue (II), by Tarek Lakhrissi

at Collective, 2023. Image Credit Eoin Carey

fig. xxvi,xxvii:

DANCE IN THE SACRED DOMAIN, by

Rabindranath

X Bhose

at Collective, 2023. Image Will Jennings

www.collective-edinburgh.art

www.tareklakhrissi.com

www.rxbhose.co.uk

COLLECTIVE

– CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY ART

Tarek Lakhrissi

Rabindranath X Bhose

Arguably one of the most impressive locations for any arts gallery in the world, Collective sits above Edinburgh at the peak of Calton Hill, with 360 degree views across the historic city and up to Arthur's Seat. The arts organisation was founded in 1984, but in 2013 began exhibiting in temporary exhibition space on the hill and, from 2018, took over the newly renovated neoclassical observatory City Dome, both designed by the architect who laid out Edinburgh New Town, James Craig.

They now oversee a collection of buildings and walled grounds, including the rentable and art-filled Observatory House, a restaurant with panoramic city views, and two gallery spaces. Inside the Observatory is I wear my wounds on my tongue (II) by Tarek Lakhrissi, a French artist and poet who explores language, desire, and queerness. Three tongue-like resin sculptures sit as if gently collapsing into the historic space, the tongue here is silent and laid out on a morgue slab as a sound work fills the brick chamber.

Next door, DANCE IN THE SACRED DOMAIN by Rabindranath X Bhose, also explores queerness with an installation comprising ritual, poetry, sculpture, and drawing. The muddy dampness of Scottish bogland is imported into the gallery, offering fertile grounds for a sculpture connecting queer eroticism and kinship with landscape and earthen histories. Connecting with bog people, bodies buried in peat and preserved through time, the artist blocks out the gallery windows with mud to conceal visitors within a tomb of their making. Calton Hill has a history as a sexual cruising ground for gay men, the sculpture formed of cock rings, cruising hankies, collars, and latex bringing forth that cultural memory of place. Boglands, and bodies contained within its sweaty, warm materiality, are here celebrated – rather than feared – as a landscape material which protects and preserves.

Tarek Lakhrissi

Rabindranath X Bhose

Arguably one of the most impressive locations for any arts gallery in the world, Collective sits above Edinburgh at the peak of Calton Hill, with 360 degree views across the historic city and up to Arthur's Seat. The arts organisation was founded in 1984, but in 2013 began exhibiting in temporary exhibition space on the hill and, from 2018, took over the newly renovated neoclassical observatory City Dome, both designed by the architect who laid out Edinburgh New Town, James Craig.

They now oversee a collection of buildings and walled grounds, including the rentable and art-filled Observatory House, a restaurant with panoramic city views, and two gallery spaces. Inside the Observatory is I wear my wounds on my tongue (II) by Tarek Lakhrissi, a French artist and poet who explores language, desire, and queerness. Three tongue-like resin sculptures sit as if gently collapsing into the historic space, the tongue here is silent and laid out on a morgue slab as a sound work fills the brick chamber.

Next door, DANCE IN THE SACRED DOMAIN by Rabindranath X Bhose, also explores queerness with an installation comprising ritual, poetry, sculpture, and drawing. The muddy dampness of Scottish bogland is imported into the gallery, offering fertile grounds for a sculpture connecting queer eroticism and kinship with landscape and earthen histories. Connecting with bog people, bodies buried in peat and preserved through time, the artist blocks out the gallery windows with mud to conceal visitors within a tomb of their making. Calton Hill has a history as a sexual cruising ground for gay men, the sculpture formed of cock rings, cruising hankies, collars, and latex bringing forth that cultural memory of place. Boglands, and bodies contained within its sweaty, warm materiality, are here celebrated – rather than feared – as a landscape material which protects and preserves.

AND MORE...

There is much else on across the city for Edinburgh Art Festival and beyond, including:

CITY ART CENTRE

Peter Howson

Shifting Vistas: 250 Years of Scottish Landscape

NATIONAL GALLERIES SCOTLAND

Alberta Whittle

Grayson Perry: Smash Hits

NATIONAL MUSEUMS OF SCOTLAND

Little Black Dress

Rising Tide: Art and Environment in Oceania

SIERRA METRO

Haein Kim

Rabiya Choudhry

JUPITER ARTLAND

Lindsey Mendick

There is much else on across the city for Edinburgh Art Festival and beyond, including:

CITY ART CENTRE

Peter Howson

Shifting Vistas: 250 Years of Scottish Landscape

NATIONAL GALLERIES SCOTLAND

Alberta Whittle

Grayson Perry: Smash Hits

NATIONAL MUSEUMS OF SCOTLAND

Little Black Dress

Rising Tide: Art and Environment in Oceania

SIERRA METRO

Haein Kim

Rabiya Choudhry

JUPITER ARTLAND

Lindsey Mendick

visitEdinburgh Art Festival runs until 27 August, with most of the exhibitions continuing later in the year. Full information available at:

www.edinburghartfestival.com

publication date22 August 2023

tags

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Aqsa Arif, Crystal Bennes, Birmingham, Sean Burns, Calton Hill, Collective, Colonisation, Andrew Cranston, Czech Republic, Decolonisation, Dorothy Towers, Edinburgh, Edinburgh Art Festival, Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop, Empire, Feminism, Film, French Institute, Installation, Ireland, Markéta Luskačová, Haven for Artists, Ingleby Gallery, Adam Lewis Jacob, Jesse Jones, Rudy Kanhye, Ryosuke Kiyasu, Tarek Lakhrissi, Lebanon, Richard Maguire, Painting, Photography, Platform, Stills, Sutherland Hussey Harris Architects, Talbot Rice, Sebastian Thomas, Sculpture, Trinity Apse, Rabindranath X Bhose, Witch

Edinburgh Art Festival runs until 27 August, with most of the exhibitions continuing later in the year. Full information available at:

www.edinburghartfestival.com

publication date22 August 2023

tags

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Aqsa Arif, Crystal Bennes, Birmingham, Sean Burns, Calton Hill, Collective, Colonisation, Andrew Cranston, Czech Republic, Decolonisation, Dorothy Towers, Edinburgh, Edinburgh Art Festival, Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop, Empire, Feminism, Film, French Institute, Installation, Ireland, Markéta Luskačová, Haven for Artists, Ingleby Gallery, Adam Lewis Jacob, Jesse Jones, Rudy Kanhye, Ryosuke Kiyasu, Tarek Lakhrissi, Lebanon, Richard Maguire, Painting, Photography, Platform, Stills, Sutherland Hussey Harris Architects, Talbot Rice, Sebastian Thomas, Sculpture, Trinity Apse, Rabindranath X Bhose, Witch

tags

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Aqsa Arif, Crystal Bennes, Birmingham, Sean Burns, Calton Hill, Collective, Colonisation, Andrew Cranston, Czech Republic, Decolonisation, Dorothy Towers, Edinburgh, Edinburgh Art Festival, Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop, Empire, Feminism, Film, French Institute, Installation, Ireland, Markéta Luskačová, Haven for Artists, Ingleby Gallery, Adam Lewis Jacob, Jesse Jones, Rudy Kanhye, Ryosuke Kiyasu, Tarek Lakhrissi, Lebanon, Richard Maguire, Painting, Photography, Platform, Stills, Sutherland Hussey Harris Architects, Talbot Rice, Sebastian Thomas, Sculpture, Trinity Apse, Rabindranath X Bhose, Witch