Material, form & process: Matt Rugg’s post-industrial

sculptures

A thematic retrospective exhibition in Newcastle’s Hatton

Gallery presents a lifetime of work from artist & educator Matt Rugg, a

sculptor & painter who used found & industrial materials in experimental works.

Over 80 sculptures and paintings made over six decades fill the gallery spaces

to create an industrial landscape of pattern, rhythm, form, and play, visited by Will Jennings.

At first glance, the passing visitor may think that the

grand gallery spaces of Hatton Gallery were being used as temporary material

storage for students at the adjoining Newcastle University Fine Art department.

Metal, plastic, and unrecognisable elements are clumped together as if awaiting

relocation, while cables and wires hang from the ceiling, suggesting the place

is in the process of decluttering and rehanging.

In fact, these assemblages are the works of Matt Rugg, an artist who worked through the radical post-war British art scene before concentrating primarily on his teaching at Chelsea School of Art, having previously lectured in painting at the university this exhibition is now displayed in. Rugg is a name that many may not have heard of, in part because of his dedication to education over publicly presenting his work from the late 1980s until his passing in 2020, but he did carry on making throughout this period, with much of this previously unpresented work making its way into a vast retrospective of the artist, titled Connecting Form, which is curated by Dr Harriet Sutcliffe.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The curation is not chronological instead loosely formed around patterns of material and motif which criss-cross his career. The opening room, however, does present a neat introduction to Rugg’s practice, with early works with formative uses of materials. There are also two vitrines, one full of photos, press clippings, and exhibition literature, the second with a collection of assorted brushes tools, and implements employed by Rugg to make his works.

These tools themselves have a sculptural quality, the artist frequently creating bespoke brushes and devices, or adapting equipment found in abandoned factories, repurposing it from industrial to creative uses. This all makes sense when looking closer at his work, with industrial materials and processes carrying all the way through the career of an artist who made work amongst post-war post-industrial landscapes.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Rugg was born in Somerset in 1935, studying classical arts and music at school whilst also discovering modernist voices like T.S. Eliot and James Joyce in his sixth form years. The collage and cutup techniques of such writers – a copy of Eliot’s Four Quartets sits in one of the vitrines, while in the other is a well-thumbed copy of The Metaphysical Poets, compressed by water into a deformed shape akin to some of the wooden tools it is next to. While Rugg’s practice was physical, requiring machinery and industrial equipment, his tools were also academic, textual, and critical.

After a year’s military service, Rugg started a Fine Art Degree at Kings College in Newcastle Upon Tyne, learning from tutors including Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton with a pedagogical approach which discussed not only contemporary fine arts, but also architecture, design, and crafts.

The interest that developed across these disciplines can be seen in early works shown in the first room of oil paintings and architectural wall-mounted wood sculptures. Archives show that Eduardo Paolozzi was a fan of the wooden constructions which contain architectural and spatial language, no doubt in part informed from the teachings of Pasmore who from 1955 had acted as Consulting Director of Architectural Design of the Peterlee development corporation, a social housing scheme within which his Apollo Pavilion would later become the centrepiece.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

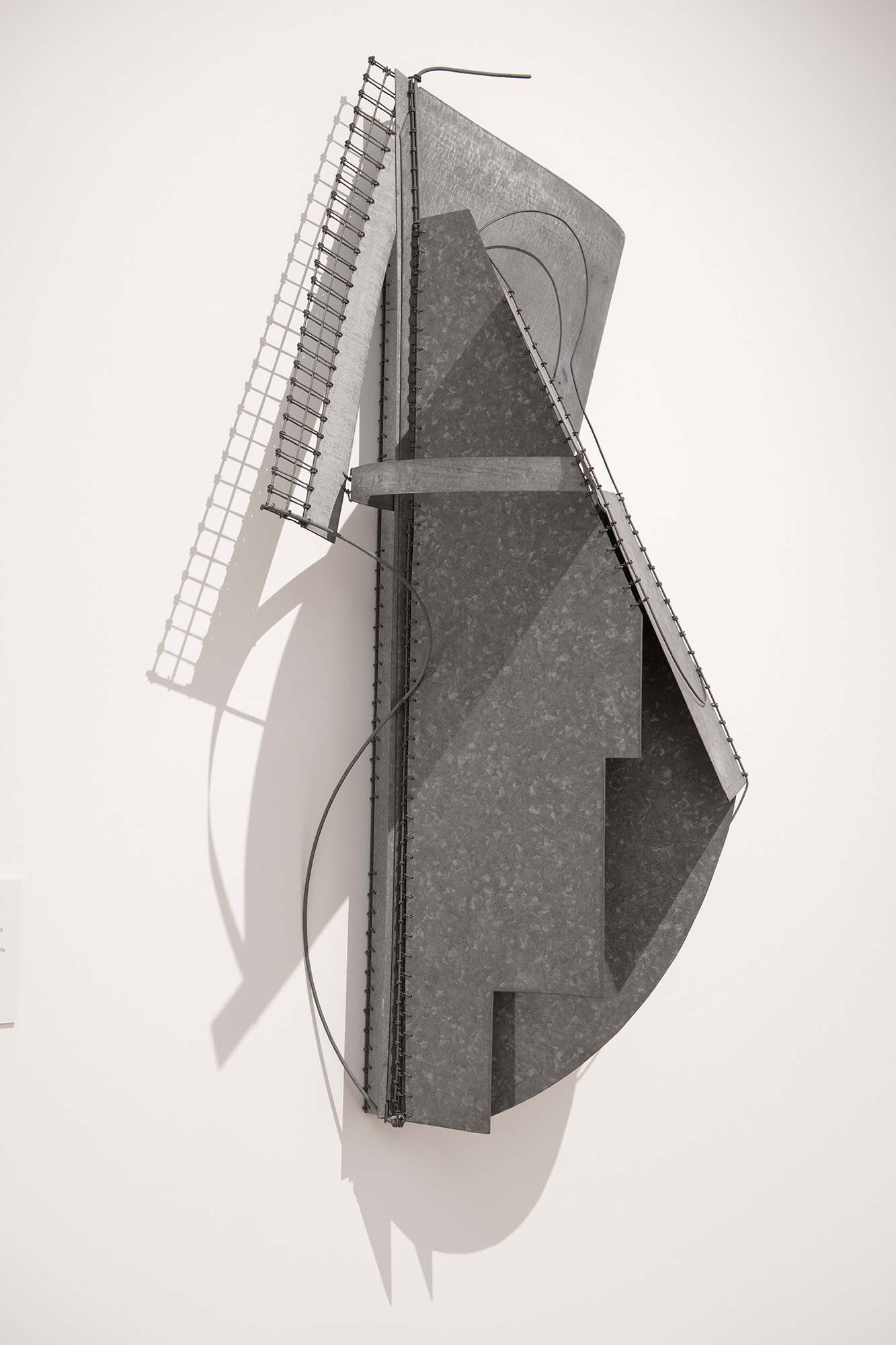

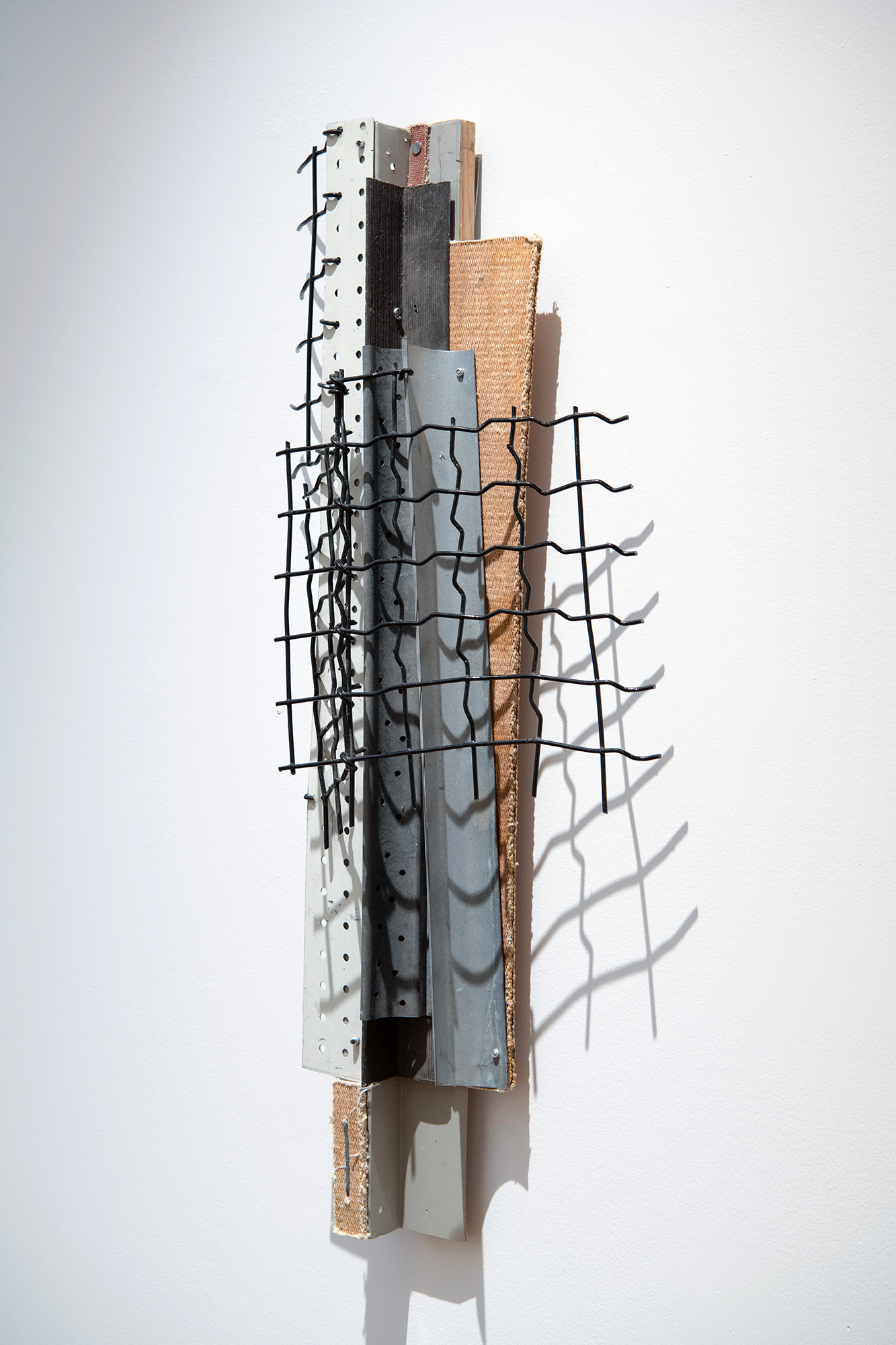

The second gallery, and grandest of the Hatton’s suite of spaces, introduces Rugg’s use of metals and found materials. These include or reference everyday and mass-produced forms including fences, cabling, barriers, and signs, though there is slippage between that which is found and reappropriated and that which is shaped and formed by the artist. These works, which span Ruggs career right through to the last years of his life, speak to his interest in industrial and post-industrial landscapes and processes.

At a distance, these plinth and wall-mounted sculptures read as eclectic assemblages, carrying through a sense of factory abandonment (Rugg often found materials from abandoned factories) and collections of scavenged pieces tightly bound together as if for collection or removal. Up close, however, and an artistic sense of play and neatness can be seen. Tennis court fencing has been meticulously cut and used as stitching and connecting tissue, metal sheets have been carefully folded to create interlocking forms, cables have been tightly wound and wrapped. There is not only an artist’s eye for composition and form, but also a fabricator’s feeling for material and process.

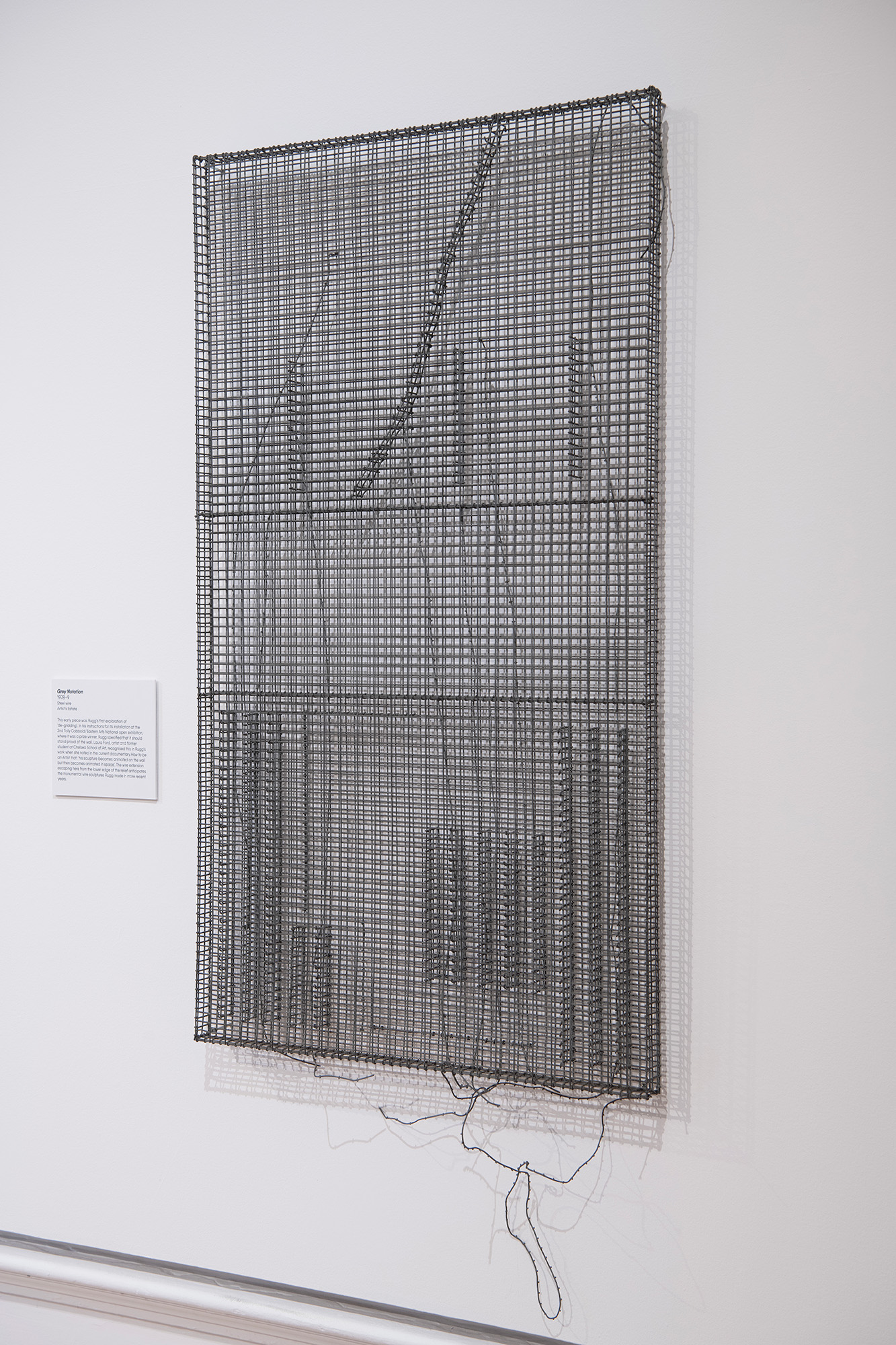

Many of the works in this array of metallic play deal with notions of the grid. The tennis court mesh recurs as a motif of how the grid can be deformed and tooled around irregularly shaped forms, while a 3-dimentional rectangular work, Grey Notation (1978-79), deforms the rigid grid through its depth and elements sited between the front and back panels – as one moves past it on the wall, the grid breaks and dances, reforms and reshapes.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The next gallery space deals with how Rugg positioned his work related to domestic settings, both in how work was presented in homes as well as with how he drew inspiration from architects such as Alvar Aalto and Gerrit Rietveld. Here, smaller-scale works are presented, including drawings – a part of his practice which he interspersed with slower, sculptural processes, but which strongly intersected in language and approach. There was a symbiosis between his mark making and how he used physical matter in space, while often the two practices directly overlapped where he may create drawings based on shadows or create a drawing which sits directly in front of a framed sculptural work.

There is care in the curation. Consideration has been given by Sutcliffe for how the works interact with the neoclassical Hatton Gallery architecture, and also how they speak to each other at various angles as the visitor navigates the room. This is Sutcliffe’s first exhibition as curator, an artist who has recently completed a practice-based PhD at the University of Newcastle and whose research in and around the university’s archive and collection introduced her to Rugg’s work.

Also, within this gallery are works which speak to Rugg’s interest in larger architectural ideas. Two works with the same title, Architectural Drawing (both 2012), read as urban maps of imaginary modernist settlements, one formed of spray painting over metallic mesh to form a texture then drawn across. Another work from 1966, Industrial Landscape II, is a pop-art infused imagining of coal power station cooling towers visible from the London-Newcastle train to this day, here replicated in painted wood and polyester resin as a playfully mutated cartoon version of the concrete forms.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Hatton Gallery may be known to many artists and architects as the home to a section of Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbarn, an entire wall of which was rescued from its Lake District location and preserved within the gallery. The small room it sits in now forms a segue between the Hatton’s two halves of exhibition space, with all curators until now ignoring it as context and treating it as momentary pause between galleries. Sutcliffe, however, engages with Schwitters with a series of drawings from the turn of the century, each which speak to the formal arrangement of the Merzbarn fragment but also to ideas of mining, geology, and landscape.

After the darkness of the Merzbarn corridor, the final room erupts in light and play. Hanging from the ceiling are seven hanging cable works collectively titled Anatomy Series (1999-2015). Ahead of all the curation for the exhibition, Sutcliffe knew that these works would be a key component, and knew that they had to hang within the largest and most modern of the Hatton spaces.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

These are also drawings to a fashion. Lines within the air, rather than on a page, and which create a twisting, winding, sketch through gravity. They are less simple than they appear in the room, Rugg wrestling with heavy materials, joining and contorting to transform from inert material into energised form, and even though they hang there is no languid limpness, the interlocking materials instead holding shapes and silhouettes through its own strength.

In her curation, Sutcliffe has weaved a compelling journey through the decades’ output that comprehensively introduces the work of an artist unknown to many, but done so to emphasise strong connections to British art and architectural history and how Rugg’s work intersects with and influenced more celebrated makers. The direct connection to Newcastle, its industrial heritage, and rich history in art education makes Connecting Form contextually interesting. While Rugg may have withdrawn from exhibiting for many years to concentrate on his teaching and pedagogical work, it’s evident that through this wideranging presentation of his works that there is still much to learn from an artist who dedicated his life to exploring material, form, and process.

In fact, these assemblages are the works of Matt Rugg, an artist who worked through the radical post-war British art scene before concentrating primarily on his teaching at Chelsea School of Art, having previously lectured in painting at the university this exhibition is now displayed in. Rugg is a name that many may not have heard of, in part because of his dedication to education over publicly presenting his work from the late 1980s until his passing in 2020, but he did carry on making throughout this period, with much of this previously unpresented work making its way into a vast retrospective of the artist, titled Connecting Form, which is curated by Dr Harriet Sutcliffe.

The curation is not chronological instead loosely formed around patterns of material and motif which criss-cross his career. The opening room, however, does present a neat introduction to Rugg’s practice, with early works with formative uses of materials. There are also two vitrines, one full of photos, press clippings, and exhibition literature, the second with a collection of assorted brushes tools, and implements employed by Rugg to make his works.

These tools themselves have a sculptural quality, the artist frequently creating bespoke brushes and devices, or adapting equipment found in abandoned factories, repurposing it from industrial to creative uses. This all makes sense when looking closer at his work, with industrial materials and processes carrying all the way through the career of an artist who made work amongst post-war post-industrial landscapes.

Rugg was born in Somerset in 1935, studying classical arts and music at school whilst also discovering modernist voices like T.S. Eliot and James Joyce in his sixth form years. The collage and cutup techniques of such writers – a copy of Eliot’s Four Quartets sits in one of the vitrines, while in the other is a well-thumbed copy of The Metaphysical Poets, compressed by water into a deformed shape akin to some of the wooden tools it is next to. While Rugg’s practice was physical, requiring machinery and industrial equipment, his tools were also academic, textual, and critical.

After a year’s military service, Rugg started a Fine Art Degree at Kings College in Newcastle Upon Tyne, learning from tutors including Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton with a pedagogical approach which discussed not only contemporary fine arts, but also architecture, design, and crafts.

The interest that developed across these disciplines can be seen in early works shown in the first room of oil paintings and architectural wall-mounted wood sculptures. Archives show that Eduardo Paolozzi was a fan of the wooden constructions which contain architectural and spatial language, no doubt in part informed from the teachings of Pasmore who from 1955 had acted as Consulting Director of Architectural Design of the Peterlee development corporation, a social housing scheme within which his Apollo Pavilion would later become the centrepiece.

The second gallery, and grandest of the Hatton’s suite of spaces, introduces Rugg’s use of metals and found materials. These include or reference everyday and mass-produced forms including fences, cabling, barriers, and signs, though there is slippage between that which is found and reappropriated and that which is shaped and formed by the artist. These works, which span Ruggs career right through to the last years of his life, speak to his interest in industrial and post-industrial landscapes and processes.

At a distance, these plinth and wall-mounted sculptures read as eclectic assemblages, carrying through a sense of factory abandonment (Rugg often found materials from abandoned factories) and collections of scavenged pieces tightly bound together as if for collection or removal. Up close, however, and an artistic sense of play and neatness can be seen. Tennis court fencing has been meticulously cut and used as stitching and connecting tissue, metal sheets have been carefully folded to create interlocking forms, cables have been tightly wound and wrapped. There is not only an artist’s eye for composition and form, but also a fabricator’s feeling for material and process.

Many of the works in this array of metallic play deal with notions of the grid. The tennis court mesh recurs as a motif of how the grid can be deformed and tooled around irregularly shaped forms, while a 3-dimentional rectangular work, Grey Notation (1978-79), deforms the rigid grid through its depth and elements sited between the front and back panels – as one moves past it on the wall, the grid breaks and dances, reforms and reshapes.

The next gallery space deals with how Rugg positioned his work related to domestic settings, both in how work was presented in homes as well as with how he drew inspiration from architects such as Alvar Aalto and Gerrit Rietveld. Here, smaller-scale works are presented, including drawings – a part of his practice which he interspersed with slower, sculptural processes, but which strongly intersected in language and approach. There was a symbiosis between his mark making and how he used physical matter in space, while often the two practices directly overlapped where he may create drawings based on shadows or create a drawing which sits directly in front of a framed sculptural work.

There is care in the curation. Consideration has been given by Sutcliffe for how the works interact with the neoclassical Hatton Gallery architecture, and also how they speak to each other at various angles as the visitor navigates the room. This is Sutcliffe’s first exhibition as curator, an artist who has recently completed a practice-based PhD at the University of Newcastle and whose research in and around the university’s archive and collection introduced her to Rugg’s work.

Also, within this gallery are works which speak to Rugg’s interest in larger architectural ideas. Two works with the same title, Architectural Drawing (both 2012), read as urban maps of imaginary modernist settlements, one formed of spray painting over metallic mesh to form a texture then drawn across. Another work from 1966, Industrial Landscape II, is a pop-art infused imagining of coal power station cooling towers visible from the London-Newcastle train to this day, here replicated in painted wood and polyester resin as a playfully mutated cartoon version of the concrete forms.

The Hatton Gallery may be known to many artists and architects as the home to a section of Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbarn, an entire wall of which was rescued from its Lake District location and preserved within the gallery. The small room it sits in now forms a segue between the Hatton’s two halves of exhibition space, with all curators until now ignoring it as context and treating it as momentary pause between galleries. Sutcliffe, however, engages with Schwitters with a series of drawings from the turn of the century, each which speak to the formal arrangement of the Merzbarn fragment but also to ideas of mining, geology, and landscape.

After the darkness of the Merzbarn corridor, the final room erupts in light and play. Hanging from the ceiling are seven hanging cable works collectively titled Anatomy Series (1999-2015). Ahead of all the curation for the exhibition, Sutcliffe knew that these works would be a key component, and knew that they had to hang within the largest and most modern of the Hatton spaces.

These are also drawings to a fashion. Lines within the air, rather than on a page, and which create a twisting, winding, sketch through gravity. They are less simple than they appear in the room, Rugg wrestling with heavy materials, joining and contorting to transform from inert material into energised form, and even though they hang there is no languid limpness, the interlocking materials instead holding shapes and silhouettes through its own strength.

In her curation, Sutcliffe has weaved a compelling journey through the decades’ output that comprehensively introduces the work of an artist unknown to many, but done so to emphasise strong connections to British art and architectural history and how Rugg’s work intersects with and influenced more celebrated makers. The direct connection to Newcastle, its industrial heritage, and rich history in art education makes Connecting Form contextually interesting. While Rugg may have withdrawn from exhibiting for many years to concentrate on his teaching and pedagogical work, it’s evident that through this wideranging presentation of his works that there is still much to learn from an artist who dedicated his life to exploring material, form, and process.

Matt Rugg (1935-2020) was born in Somerset, England in 1935. He studied at King’s College, Newcastle from 1956 where Lawrence Gowing was Professor. He was taught by and then worked with Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton. With a Travelling Scholarship awarded after gaining a First Class degree, he visited collections in Holland, Germany and Belgium. As Tutorial Student he taught at Newcastle for two years, and was then appointed by Kenneth Rowntree as Lecturer in Painting for a further two years, before moving to Chelsea and establishing his studio in South London.

Matt’s first one-man shows of constructions in wood, and later in metal, at the New Art Centre in London in 1963, 1966, and 1970 won critical acclaim. This led to other solo exhibitions including in Milan in 1965 and other group exhibitions including Paris in 1967. During this time his work was acquired for public collections including the Tate Gallery, the British Council, the Arts Council, the Contemporary Arts Society, and regional collections.

Matt continued to work in his studios producing sculpture and drawings until his death on 6 June 2020.

www.mattrugg.com

Dr Harriet Sutcliffe is an artist, curator and researcher.

She is Associate Lecturer at the University of Newcastle, where she completed

her PhD, focused on the Basic Course at King’s College, in 2021. Recent

projects include Undutiful Spirit, a Baltic Artist's Archive Residency (2022),

and Matt Rugg: Notations, Passages, Intervals at the Cut Gallery (2022). She is

curating Matt Rugg: Connecting Form at the Hatton Gallery in autumn 2023.

www.harrietsutcliffe.co.uk

The Hatton Gallery at Newcastle University has been at the heart of cultural life in the Northeast since the early 20th century. Founded in 1925 and named in honour of Professor Richard George Hatton, professor of what was then the King Edward VII School of Art, Armstrong College, Durham University. He subsequently became Head of the Department of Fine Art at Newcastle University.

In October 2017 the gallery underwent a £3.8 million redevelopment to conserve the historic and architectural elements of the Grade II listed building while creating a modern exhibition space. The funding also enabled urgent conservation and better interpretation of the iconic Merz Barn Wall by Kurt Schwitters, one of the most significant figures in 20th century art. The wall was brought to the gallery in 1965 and incorporated into the fabric of the building.

The Hatton Gallery’s diverse collection includes over 3,000 works from the 14th – 20th centuries. Key pieces in our paintings collection include works by Francis Bacon, Prunella Clough, Richard Hamilton, Palma Giovane, Patrick Heron and William Roberts. Works on paper by artists including Thomas Bewick, Thomas Hair, Wyndham Lewis, Linder and Paula Rego are also held

www.hattongallery.org.uk

www.harrietsutcliffe.co.uk

The Hatton Gallery at Newcastle University has been at the heart of cultural life in the Northeast since the early 20th century. Founded in 1925 and named in honour of Professor Richard George Hatton, professor of what was then the King Edward VII School of Art, Armstrong College, Durham University. He subsequently became Head of the Department of Fine Art at Newcastle University.

In October 2017 the gallery underwent a £3.8 million redevelopment to conserve the historic and architectural elements of the Grade II listed building while creating a modern exhibition space. The funding also enabled urgent conservation and better interpretation of the iconic Merz Barn Wall by Kurt Schwitters, one of the most significant figures in 20th century art. The wall was brought to the gallery in 1965 and incorporated into the fabric of the building.

The Hatton Gallery’s diverse collection includes over 3,000 works from the 14th – 20th centuries. Key pieces in our paintings collection include works by Francis Bacon, Prunella Clough, Richard Hamilton, Palma Giovane, Patrick Heron and William Roberts. Works on paper by artists including Thomas Bewick, Thomas Hair, Wyndham Lewis, Linder and Paula Rego are also held

www.hattongallery.org.uk

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

visit

Matt Rugg: Connecting Form is on at The Hatton Gallery in

Newcastle University, until 13 January 2024. Further information available from: www.hattongallery.org.uk/whats-on/matt-rugg-connecting-form

An exhibition book by Michael Bird with Harriet Sutcliffe

has been produced by Lund Humphries, further information available at: www.lundhumphries.com/products/matt-rugg

images

fig.i LAll images of Matt Rugg: Connecting Form, The Hatton Gallery,

Newcastle University. Photographs © Colin Davison, courtesy Hatton Gallery.

publication date

21 October 2023

tags

Alvar Aalto, Apollo Pavilion, Assemblage, Cable, Chelsea School of Art, Cooling towers, Craft, Design, Education, Factories, Fencing, Richard Hamilton, Hatton Gallery, Industrial, Industry, James Joyce, Metal, Merzbarn, Newcastle, Painting, Peterlee, Eduardo Paolozzi, Victor Pasmore, Plastic, Gerrit Rietveld, Matt Rugg, Kurt Schwitters, Sculpture, Steel, Tools, TS Eliot, Harriet Sutcliffe, University of Newcastle, Wire, Wood

An exhibition book by Michael Bird with Harriet Sutcliffe has been produced by Lund Humphries, further information available at: www.lundhumphries.com/products/matt-rugg